Arno, Teetering Between Emotion and Banality

The Americans have Tom Waits, the Flemish have Arno. The singer with the rasping voice is undoubtedly the most colourful and most cosmopolitan rocker that Flanders has ever produced. Arno, né Hintjens (b. 1949), delights in putting listeners off balance. At the same time though he is a master of the art of self-mockery. Regarding himself more as a flop star than a pop star, a clown as much as a singer, he has himself addressed alternately as Charlatan and European Cowboy.

This Ostend-born resident of Brussels first made himself heard as a singer and harmonica player in the early 1970s, with blues-oriented groups such as Freckleface and Tjens Couter. He would only make history between 1980 and ’85 as the front man of the totally unique TC Matic, with whom he performed a blend of new wave and James Brown’s funk heritage on countless stages both in Belgium and abroad, and wrote classics like ‘O La La La’ and ‘Putain Putain’ (Bloody Whore). From the latter we remember the immortal line, ’k hèn e klintje, moar ’t schiet verre’ (I’ve got a small one, but it shoots a long way).

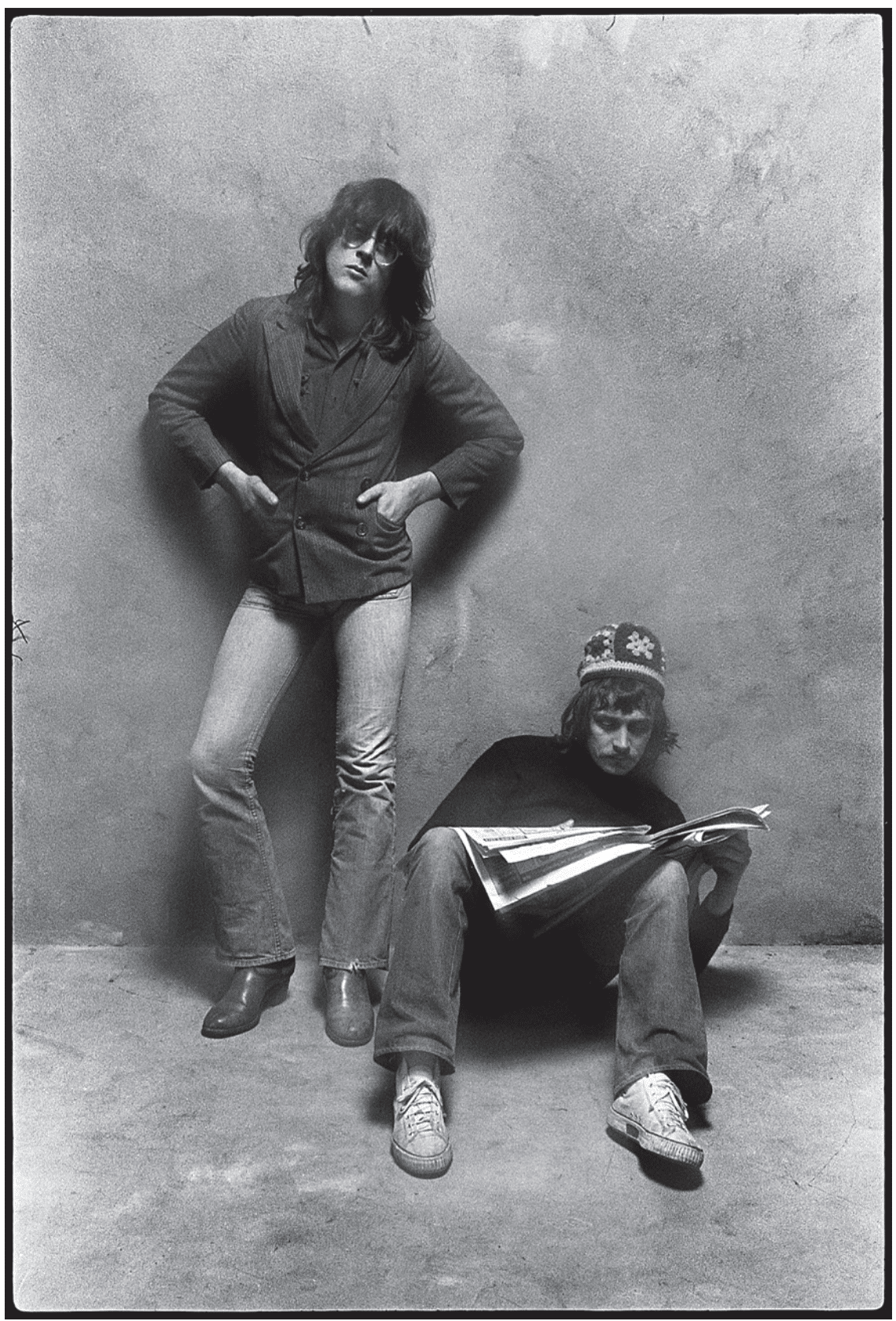

Tjens Couter, 1976

Tjens Couter, 1976© Danny Willems

Inimitable idiom

Arno is the archetypal Belgian who speaks several languages – English, French and his Ostend dialect – but doesn’t really master any of them. His inimitable idiom, for which he himself thought up the term Arnolais, certainly didn’t stand in the way of an international career. Since the singer has been working under his own name, he has collaborated with well-known producers such as Holger Czukay and John Parish, done concerts in both Montreal and Moscow, been heard in the Flemish version of Disney’s Toy Story and figured as an actor in various films. In between times he disappeared into bands like Charles & Les Lulus, The Subrovnicks and The White Trash European Blues Connection.

Arno makes no secret of the fact that he’s not very practical. ‘The only thing I can really do is make music’, he says. ‘And that’s all I need to be happy. For me, music is the ultimate refuge; something that makes me forget my worries. Thanks to the path I’ve chosen I can be a voyeur. I’m not much of an autobiographer, I prefer to observe. I absorb the things I see and spit them out again later. But I am in charge of my own life, so I don’t need to join in any parade. And since I’ve been making music for over forty years, I’m well aware of all the pitfalls. I’m not worried about losing my recording contract any more. I know I’ll be making music till I die.’

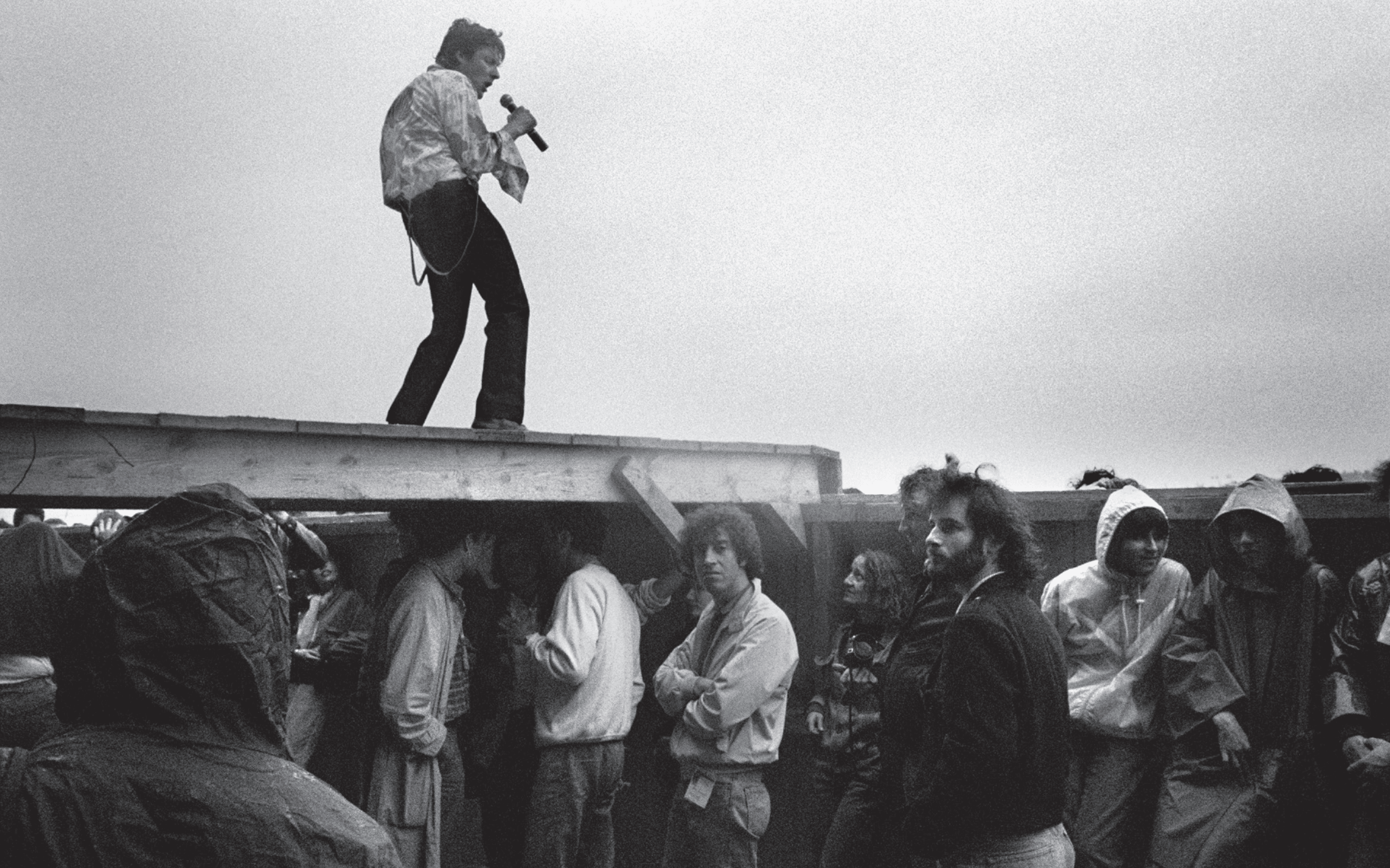

TC Matic, Brest, France, 1984

TC Matic, Brest, France, 1984© Danny Willems

Arno’s lyrics are the result of automatic writing: they come out in one spontaneous gush. In the singer’s opinion, they risk sounding forced if you think about them too much. ‘Most of the stuff I record sounds radically different two years later. Your songs make a journey and as an artist you journey with them. Writers, painters or film directors make things they can’t change afterwards. Songs, on the other hand, are pliable. They keep developing.’

Hintjens’s father served in the RAF during the Second World War and brought English-language music culture back home with him. ‘I still know all Vera Lynn’s songs. Mother, on the other hand, was crazy about Mistinguett. These artists all left their mark on me. And, of course, I grew up in a port city. Twelve packet boats a day called into Ostend, bringing the whole world with them – including a lot of imported records from England and the US.’

Jukeboxes were inestimably important for Arno’s musical education. ‘As a young boy in the ‘60s, I watched the illuminated glass, fascinated as the records went round and round. You had categories like ‘rock’, ‘slow’, ‘cha-cha-cha’, ‘rumba’ – perhaps that’s why my tastes in music are so eclectic?’

Although Arno has lived in Brussels for years now, the queen of seaside resorts still draws him like a magnet. ‘The North Sea is the only sea in the world that changes colour, smell and sound every day. It’s at its best in autumn and winter. You can see it in paintings by Spilliaert, Ensor and Permeke, too – the light, the brilliance. My songs are a bit like the waters of the North Sea. They never sound the same two days in a row.

The blues, over and over again

The Bathroom Singer thinks of his recordings – a good thirty of them by now – as snapshots: they show exactly who he was at the time he made them. ‘When I listen to Ratata now, I see a period in which I looked at the world through a haze of alcohol every day. I used to take dope, because it was fashionable and everyone around me was doing it. But it didn’t take me long to realize that you don’t need drugs to produce good work. I still like to drink, but never at home. I’m a social drinker, ha ha.’ Yet he always managed to avoid extreme excesses during his career. ‘Fortunately I only really became well-known when I was a bit older. Fame is a trap. As soon as you let it go to your head it becomes dangerous.’

Arno and Danielle, 1988

Arno and Danielle, 1988© Danny Willems

The artist reserves his respect mainly for ordinary people ‘with balls’. For badly prepared interviewers and TV talk show hosts, on the other hand, he can be a real scourge. Like Serge Gainsbourg he can sometimes be a bit of a loose cannon. ‘In this business people are forever putting on an act. But I’m not a product, you know?’

Arno admits that the exuberant singer we know from the stage is actually a rather shy guy at heart, hence a song like ‘Dancing Inside My Head’. In the world of the imagination all the inhibitions that get in the way in real life disappear. ‘That’s why I’m a musician. Music is basically therapy for me. What for? For the bullshit that’s all around us. I’m just my own shrink.’

During his long career Arno has borrowed from a great number of styles. But whatever he does, it always sounds like the blues. You notice that with his interpretations of other people’s work too. ‘I do everything in my own tempo and that’s always slower than the original. Yeah, the blues, they’re my roots. I picked up the genre from The Rolling Stones. But if you go looking for the source you’ll usually find better stuff: Willie Dixon, Fred McDowell, Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson… I admire André Hazes just as much though. Blues from the working-class quarters in Amsterdam, let’s say. I’m pretty schizophrenic; I listen to all sorts of music. I’ve never followed trends. You won’t just find Captain Beefheart in my collection, there’s Abba, Dean Martin and French chansons too. A good song is a good song.’

Apart from pop standards by David Bowie and Nina Simone or chansons by Jacques Brel and Claude Nougaro, Arno regularly flirts with light music. He recorded ‘Viva Boema’ with TC Matic, and his interpretation of Salvatore Adamo’s ‘Les filles du bord de mer’ never fails to win over the audience.

The singer is always curious to see what will happen when he lets two musical worlds collide. ‘I’ve been lucky enough to write a few classics that are easy to rework. They’re ditties that the audience wants to hear night after night, but to keep them interesting for myself I stick in something new every now and then.’ Arno once played the TC Matic repertoire with a brass band, for example. He has played with African musicians from the Matongé district in Brussels, and gave his songs an exotic facelift with a group consisting mainly of Turks and Moroccans. ‘You can push your limits every day in music. I get a huge kick out of it.’

Solitary by nature

He doesn’t have a problem with artists selling illusions, because music is about laughter and tears. People buy a recording for a particular atmosphere and go to concerts to forget their everyday routine. ‘Rock, jazz, funk, house – they’re all the same, they’re all entertainment. But I don’t give a damn

about musicians that behave like businessmen or drivel on about their own problems. When I write a song I’m like a mirror. People buy what they can recognise.’

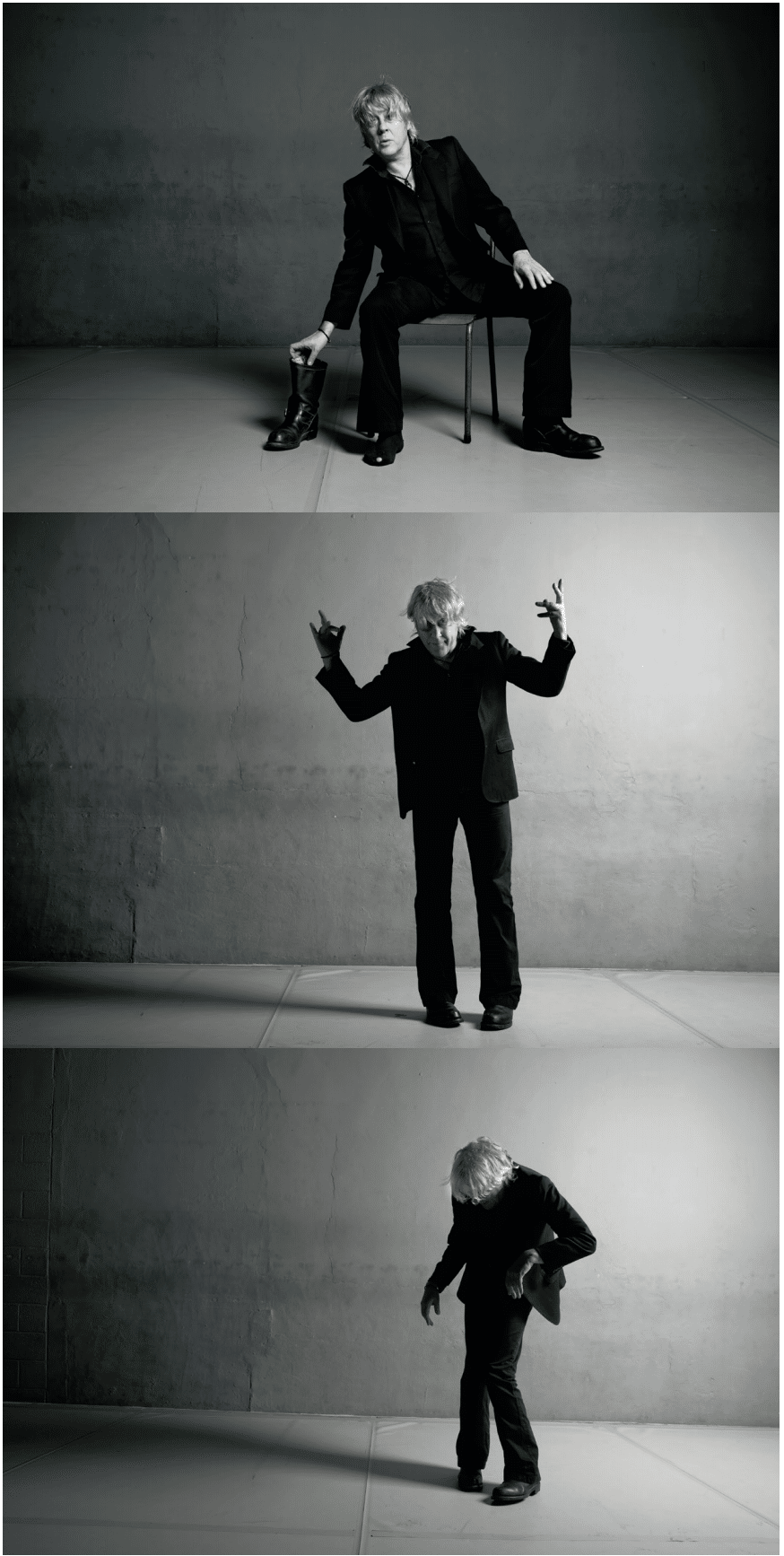

Arno, 2010

Arno, 2010© Danny Willems

Many of his songs are conceived as portraits of women, although for Arno the poetic and the prosaic, the moving and the banal always go hand in hand. In ‘Les Yeux de ma mère’ (My Mother’s Eyes) he sings: ‘C’est elle qui sait que mes pieds puent / C’est elle quit sait comment j’suis nu / Mais quand je suis malade / Elle est la reine du suppositoire.’ (‘She knows my feet stink / She knows what I look like naked / But when I’m ill / She’s the suppository queen.’)

However, while the mamsels and the madams play a central role in his work, they embody both heaven and hell for the artist. ‘Men are really the weaker sex’, he explains. ‘You notice that during wars especially. Women make less fuss about pain; they deal with illness and pain much more bravely. Maybe it’s because they carry little’uns for nine months?’

There’s no lack of humour in Arno’s work. But there’s a certain amount of darkness in it too. His biggest nightmare, for example, is the life cycle he sums up in one of his songs as ‘Have kids / Get bored / Get fat / Split up’. ‘I couldn’t live like that myself. But sometimes you have to go through hell to see heaven. I once felt the beginning of what I described in ‘From Zero to Hero’ and I knew right away that was not for me.’

In his songs he portrays himself alternately as a Lonesome Zorro and a Solo Gigolo, because Arno is first and foremost an individualist, who would rather stand on the sidelines than participate. ‘I’m solitary by nature. One of the things I’m good at is being alone. I like living by myself and I always go out by myself. I definitely don’t want to be a sheep in the flock.’

Life in a melting pot

Arno is not the sort of artist that juggles with clever slogans or enlightening political messages. The fact that you can hear exotic musical instruments on his recordings is a statement in itself. ‘It’s simple. If there’d never been Moroccans living in Brussels I’d never have tasted couscous. And it just so happens I’m nuts about couscous. I don’t want sausages and mash on my plate every day, do I? I’ve learned a lot from Arabic music too. I live in a street where several nationalities and cultures interact and I think that’s a huge advantage. The people I meet when I go to, let’s say, Poperinge aren’t enriching. But if my Moroccan neighbour’s daughter gets married and they party and sing for four whole days, that’s incredible. The delicious food, the hospitality – you’d think you were in Marrakesh, but it’s happening next door to you. You don’t even need to travel to experience it all.

‘When I walk around in Barbès, an immigrant district in Paris, it’s like a feast of smells, sounds and flavours. That’s the essence of our existence in my opinion. We live through our senses, don’t we? If you were surrounded only by people of your own kind you’d be a poor sod. Apparently Flanders is a country now – with six million inhabitants, for Christ’s sake. That’s about half the size of a city like New York. A melting pot produces so much creativity. We wouldn’t be sitting here talking now without the Germans and the British that I met as a kid in Ostend.

‘I admit I still have that underdog feeling that’s so typical for Flemings. Perhaps it’s because I stutter. When people used to ask me about my job and I answered “rock musician” they would look at me as if I came from Mars. But nowadays it seems alright. The French even knighted me for it ten years ago. OK, so perhaps it’s a kind of acknowledgement, but at the same time I wonder: Why me? It’s all so relative. Sometimes you go up in the world and sometimes you go down. I’ve been through it all.’

So why has he increasingly sung in French since À la française

(1995)? Obviously his popularity in France and Switzerland has got something to do with it. But there’s another reason too, he says. ‘I’ve got two children by a French woman, and if you sleep with the dog you get fleas. I just happen to write differently about the things I experience in French. On the other hand, if I dream up a rock number in the tradition of The Faces or Dr Feelgood, I know instinctively I have to sing it in English – because the French can’t make that sort of music.

Arno, 2010

Arno, 2010© Danny Willems

Recalcitrant free spirit

One of Arno’s key songs is called ‘Vive ma liberté’. It portrays him as a recalcitrant free spirit through and through. ‘I constantly come across people, in music and outside, who try to tell me what I should or shouldn’t do. Then I do the opposite, on principle. They’re always trying to screw you. You’ve got to fight that. Drop your guard, in art or in music, and you’re vulnerable. You’ve got to fight every day to be yourself.’

Arno hates anything soulless and artificial, too. In his work he speaks out against greedy rich people, know-alls and people with ‘cobwebs in their heads’. He can’t stand nationalism, corruption, the extreme right, unrestrained consumption, MTV, the degeneration of his city, the dumping of toxic waste, terrorism in holiday resorts, the demise of idealism and women’s magazines that make their readers unhappy with ideals of beauty that no one can live up to.

Those in positions of authority are often on the receiving end on his CDs too: ‘De politiekers zin oan’t diskuteren / Ut ulder valsche mond / Komt er niets dan stront’ (‘The politicians are arguing again / From every lying mouth / Comes nothing but crap’), goes one of his not very flattering songs. ‘When I see a politician on TV, I often wonder: what’s he like in bed? Does he mess about as much there too?’ grins the crooner.

He loathes institutionalised thought systems just as much. ‘Aucune réligion peut nous sauver’ (‘No religion can save us’), he sings somewhere. And: ‘Moi, j’aime dieu, mais je fais ce que je veux’ (‘Me, I love God, but I do what I like’). Arno does feel attracted to Buddhism though. ‘But that’s more of a philosophy than a religion. Buddha isn’t really worshipped; you’re not expected to follow him, because he’s in you. You have to follow your own path, and are only accountable to yourself. Everyone knows the difference between good and evil, don’t they? If you think a bit and are honest with yourself, you can get on very well without God.’

A preference for the stage rather than recordings

Arno may have made an impressive number of albums, yet he insists that he only makes recordings to be able to perform, never the other way round. ‘What you’ve made breathes and evolves on the stage. And feedback from the audience always provides an extra dimension.

‘I’m only a mediocre musician myself, so I surround myself with the best in the business to compensate. After all, Arno isn’t just me. Arno is all the guys who sit in the studio with me or do the round of festivals in summer – real musicians, who don’t just sell their souls to anyone who comes along. I wouldn’t exist without them. But I can only work with people I trust. The question of whether they are technically skilled always takes second place. I function best in a family atmosphere. It’s important to me not to have to explain anything. After all, music comes from feelings.

‘I’m impulsive in everything I do and I’m happy to take the consequences. No regrets. Because although I’ve been on the road a long time, I don’t feel like I’m retracing my steps. I’m always progressing, slowly but surely. What’s important is to know what you can and can’t do. There’s no point in trying something you don’t feel. All things considered, I’ve been blessed, yes. I travel and get paid for it, see the world thanks to my music. I can’t say it often enough: I’m a lucky devil.’

This article was first published in the yearbook The Low Countries 2016, № 24, pp. 134-141.