Belgium Denounces Its Colonial Past, and the Netherlands Lags Behind

For decades the Netherlands has been wrestling with its colonial past in Indonesia. Now there is a research report that shows that the armed forces used extreme, structural violence during the Indonesian independence struggle of 1945-1949. Belgium has also researched its colonial history but has taken a different approach with the Congo Commission. Anne-Lot Hoek, the author of The Battle for Bali, examines what their different approaches mean in terms of dealing with a fraught past.

In the Netherlands, the long-awaited results of the four-year research project on the colonial war in Indonesia were published on 17 February 2022, in the report Independence, decolonisation, violence and war in Indonesia 1945-1950 (Onafhankelijkheid, dekolonisatie, geweld en oorlog in Indonesië 1945-1950), the work of three research institutes (more on this later). In Belgium, a commission led by politician Wouter De Vriendt was tasked, in 2020, with researching the Congo Free State as well as Belgium’s colonial past in Congo, Burundi and Rwanda, its impact and the actions that should be taken as a result. In late 2021 the commission’s team of experts came out with some recommendations to politicians in the form of a three-part report.

Both countries, then, subjected themselves to thorough self-examination. As a commentator on the Dutch debate, the author of the book The Battle for Bali. Imperialism, resistance and independence 1846-1950, (De strijd om Bali. Imperialisme, verzet en onafhankelijkheid 1846-1950, De Bezige Bij, 2021) and a participant in a subproject of the Dutch research, I will discuss the differences between the Dutch and Belgian approaches to dealing better with their colonial past.

Colonial past misunderstood

In the Netherlands, the colonial war between 1945 and 1949 still gives rise to intense public debate. It first became an issue in 1969, when the veteran Joop Hueting testified about war crimes on national television and the government commissioned an official investigation, the so-called ‘note on excesses’ (Excessennota). On the basis of the note, the government drew the conclusion that military violence had been “incidental”. It was a very muted message, which also affected the historiography. Pressure from the veterans’ lobby played a role in this, but it was compounded by an historical establishment that looked at history mainly from the perspective of those in power. For a long time, historians continued to refer to the colonial war as “policing activities”, barely wrote about violence and did insufficient research in Indonesia.

It was known in Dutch academic circles that violence during the Indonesian War of Independence had been structural, yet that was only confirmed very recently, in 2015 at the University of Bern, in the Swiss-Dutch historian Rémy Limpach’s doctoral thesis. The publication of his thesis a year later was the last straw that persuaded politicians to proceed with a major investigation. Indonesian relatives had already won a case against the Dutch state in 2011, with the support of Jeffry Pondaag and lawyer Liesbeth Zegveld. Journalists, including myself, had also stepped up the pressure in the media with new facts. So, in 2017, a study of the war in Indonesia began under the flag of the Royal Institute of Linguistics and Anthropology (KITLV), the Netherlands Institute of Military History (NIMH) and NIOD’s Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies. It might well be called historic.

The fact that the 1945-1949 war in Indonesia was rooted in a violent colonial past is still not sufficiently emphasised in the Netherlands

The focus on the violent departure from “the Indies” is already a key difference with the debate and research in Belgium, where the focus is not on the withdrawal from the colony, but on the whole imperial period, starting in 1885, with Leopold II’s Congo Free State, and ending with the Belgian Congo, which lasted from 1908 to 1960. This is also one of the main reasons why in the Netherlands, far more than in Belgium, the facts are still so strongly disputed. The fact that the 1945-1949 war in Indonesia was rooted in a violent colonial past is still not sufficiently emphasised in the Netherlands. Yet that is absolutely crucial to a better understanding of why the war was so violent. During my own research, for instance, I discovered that the long-standing Balinese struggle against colonial oppression was an important explanatory factor and that the colonial culture of violence was reflected in military and political strategies. Terms like “pacification” and “subjugation” and ideas about Indonesians not being equals, reverberated in the historiography.

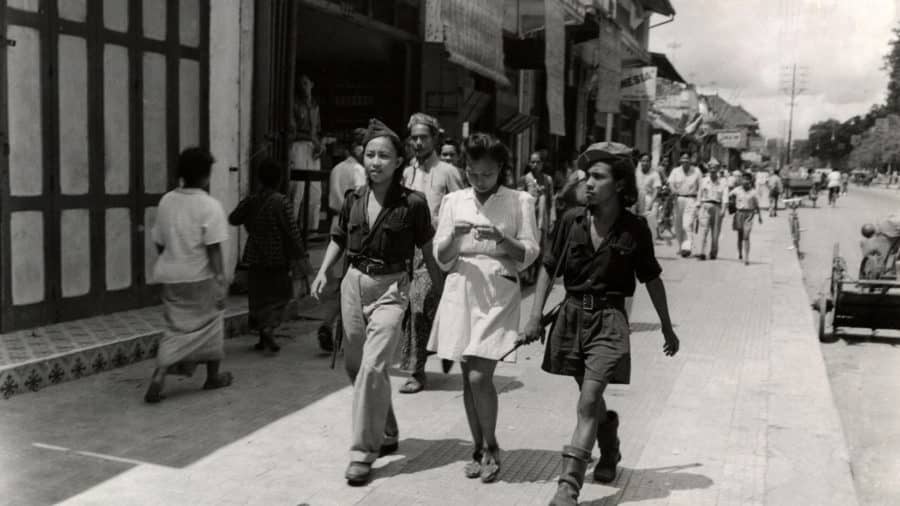

A group of Republican fighters to be interrogated by the Intelligence and Security Group in Sidikalang, Northwest Sumatra, early 1949.

A group of Republican fighters to be interrogated by the Intelligence and Security Group in Sidikalang, Northwest Sumatra, early 1949.© National Archives

Impact on the present

Something else that is not strong in the national consciousness of the Netherlands is that the colonial past has an impact on the present. However, the Belgian approach, the appointment of a commission in contrast to the Dutch investigation, pays much attention to this. The Belgian commission focuses on experts’ recommendations on how to deal better with the colonial past and its legacy. In addition to the history, the relationship between colonialism and contemporary racism and reconciliation is an explicit part of the Belgian commission’s task. So is the economic impact on the colonized countries, a subject the Netherlands ignores. That approach undoubtedly has to do with the immediate reason for the parliamentary commission in Belgium: the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 and the daubing of the statue of Leopold II in Brussels. These protests resonated strongly in the Congolese diaspora in Belgium. So, in Belgium racism plays a major role in the commission’s research, alongside the atrocities in Congo under Leopold II, the issue of the abduction of mixed-race children, the assassination of the first Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, led by Belgium, and looted artworks.

A defaced statue of Leopold II

A defaced statue of Leopold IIThe broader Belgian view of both the colonial past and the present is also presumably linked to the fact that there seems to be more consensus about the facts in Belgium than in the Netherlands. “Enough research has been done by historians in the past to be able to conclude that colonial policies were particularly violent”, remarks journalist Elien Spillebeen from MO* Magazine. When, in the 1990s, the Netherlands was still debating the “exceptional” nature of Dutch imperialism in Indonesia, Belgium was writing about its gruesome colonial past in Congo as racist and based on exploitation. In 2010, moreover, the Belgian author David van Reybrouck wrote the bestseller Congo, which also increased awareness in society of the colonial past.

Not everyone in Belgium thinks there is sufficient consensus about the facts though. Indeed a number of scholars are of the opinion that historians should do more research into the facts. Former VRT journalist Peter Verlinden, who has reported on Congo since the 1980s, also believes there should be more thorough historical research and is not a supporter of the political commission. “It’s the political game that dominates behind the scenes.”

Former VRT journalist Peter Verlinden: 'It’s the political game that dominates behind the scenes'

Nevertheless, despite the criticism of the political design and organisation of Belgium’s self-examination, racism and colonialism as occupation and as a violent system are the premises of the experts’ report, which is more progressive than the Dutch approach.

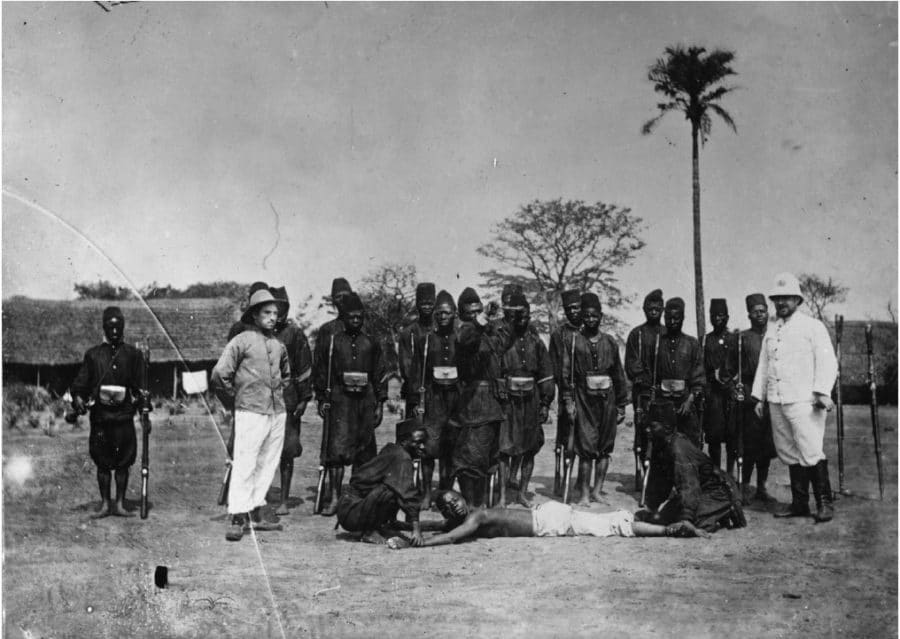

Administration of whippings in Belgian Congo

Administration of whippings in Belgian Congo© Source: RMCA, HP.1953.49.393 (unknown photographer)

A Dutch problem

One of the shortcomings of historical research in the Netherlands has long been the scant attention paid to Indonesian perspectives, and there has been too little commitment to research in Indonesia itself. Ordinary Indonesians’ memories of colonialism are still wrongly seen by leading historians as private “experiences” rather than an important part of the research, which is also reflected in the Dutch project design. After conducting more than a hundred interviews and research in Bali, I was able to come forward with not only the political motives of the leaders of the struggle but also a system of prison camps where prisoners were systematically tortured and often executed. A system like this falls outside the colonial archives and cannot be reconstructed from them. Nonetheless, it did happen, which is why research in the field is important.

Political scientist Nadia Nsayi: 'The expert report certainly included the Congolese perspective'

The fact that Dutch researchers worked together with Indonesian researchers and that there was a meaningful dialogue about the war between them was an important achievement. But unfortunately, the project design was organised in such a way that this cooperation only occurred in two of the nine subprojects and, with the exception of the epilogue, Dutch historians wrote the end report. That is a significant difference with the Belgian research, which was carried out by a multidisciplinary team including the Congolese historian Elikia Mbokolo and the Congolese-Belgian historian Mathieu Zana Etambala. Art historian Anne Wetsi Mpoma, an activist and expert, contributed to the section on racism. “The expert report certainly included the Congolese perspective”, says Nadia Nsayi, political scientist and author of the book Daughter of decolonisation (Dochter van de dekolonisatie, EPO, 2020) in which she recounts her Belgian-Congolese family history.

The bodies of c. 30 Indonesians, arrested and shot by Dutch special forces in retaliation for an attack on the prison and homes of two Dutch officials in Barroe kampong, South Sulawesi, early January 1947. Shortly hereafter, another 24 prisoners were executed. By order of the commander, the bodies were left on the ground for half a day.

The bodies of c. 30 Indonesians, arrested and shot by Dutch special forces in retaliation for an attack on the prison and homes of two Dutch officials in Barroe kampong, South Sulawesi, early January 1947. Shortly hereafter, another 24 prisoners were executed. By order of the commander, the bodies were left on the ground for half a day.Source: H.C. Kavelaars, NIMH

The lack of Indonesian input in the Dutch design undoubtedly had also to do with the fact that Indonesian historians saw “violence” as a primarily Dutch problem. They wanted a dialogue with Dutch historians about a broader colonial story, as well as to challenge the way their own national history is framed. But that did not fit the Dutch project frameworks, which were focused on the violence committed by their own armed forces. The Indonesians did choose to participate in the project; head researcher Bambang Purwanto saw the collaboration as an important opportunity for both countries. But they expressed themselves independently of the Dutch project under their own title, Proclamation of independence, revolution and war in Indonesia 1945-1950 (Proclamatie van onafhankelijkheid, Revolutie en Oorlog in Indonesië 1945-1950). Few could miss the irony of this situation.

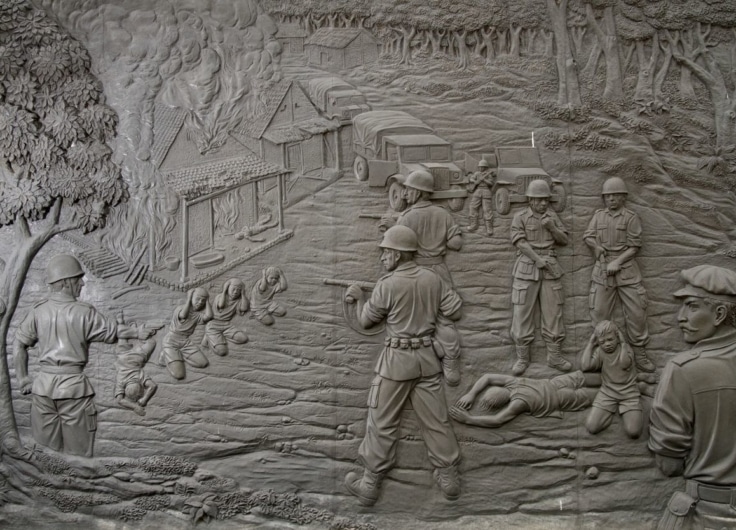

The annual commemoration at the war memorial in Balinese Marga in 2014.

The annual commemoration at the war memorial in Balinese Marga in 2014.© Anne-Lot Hoek

A cannonball to shoot a mosquito

Soon after it started, in late 2017, there was criticism of the design of the Dutch project from several quarters. Critical scholars and publicists like Ethan Mark and Lara Nuberg, as well as activists like Jeffry Pondaag and Franscisca Pattipilohy felt that the design was too colonial and input from Indonesians too limited. Veterans groups and voices from within the Indonesian community, such as Hans Moll from the Federatie Indische Nederlanders, a federation for Dutch people with roots in the former Dutch East Indies, considered in turn that the design had an overly anticolonial political bias.

“Discussion” of the research intensified and attempts at public intimidation by activists against participating researchers became a common occurrence. The Indies monument in The Hague, for victims of Japan during the Second World War in Asia, was also daubed with paint. There was intense debate about the Bersiap, Indonesian violence that broke out in 1945 against the Dutch, Chinese, Moluccans and even Indonesians. The Bersiap had been added to the project as a research topic at the demand of the government. One group of critics felt that this demand seemed to imply that the war had begun with the Bersiap, whereas the history of the colonial past should be the main focus, and the other group felt that Indonesian violence was not sufficiently emphasised in the project design. Tempers ran high again in February 2022 over the interpretation of the term Bersiap in the Revolusi exhibition in the Rijksmuseum (11 February to 5 June 2022). Even before the exhibition had opened, charges were filed against both a Dutch and an Indonesian (guest) curator and the General Director of the museum, and the museum was threatened with violence.

Campaign image of the Revolusi exhibition at the Rijksmuseum

Campaign image of the Revolusi exhibition at the Rijksmuseum© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The discomfort that presumably arose among the project leaders of the Dutch study concerning outside criticism must have contributed to the ponderous way in which criticism was dealt with within the project. A discussion about the solo authorship of the historical synthesis – the concluding summary – by just one of the project directors (Gert Oostindie) had to be forced open under pressure from a number of researchers. Participation in the public debate led not infrequently to disapproval from above. The objection that colleague Esther Captain and I expressed in the weekly newsmagazine De Groene Amsterdammer, in 2019, in an article by Niels Mathijsen – that the planned synthesis still lay in the hands of a single director, despite all the criticism, and that no international researchers were involved in the synthesis – was condemned by the project leadership. And that was neither the first nor the last time that there was a negative reaction to researchers in the media. As a fellow researcher aptly put it, the project management was using a “cannonball to shoot a mosquito”. I feel that that attitude was not in line with the word “polyphony”, which the management itself used so often.

What also echoed in the criticism – both from outside and inside the project – is that the research design and final responsibility lay mainly in the hands of three Dutch institutions and project managers. In Belgium, the expert team was less organised from above and an important role in the introduction to the historical synthesis was also played by (female) historians from universities, like Sarah Van Beurden (Ohio State University) and Gillian Mathys (University of Ghent). Moreover, the Belgian team also consisted of experts from other disciplines and an activist expert, Anne Wetsi Mpoma. Nadia Nsayi, therefore, finds it remarkable that it is possible, in the Netherlands, for a number of institutions to have free rein in organising such an important study. “That would certainly not happen in Belgium”, she says.

War crimes as well as the colonial system

The results of the Dutch study were announced on 17 February 2022, with the publication of the final report, Over de grens (Beyond the pale). I had already distanced myself from it in 2020 due to my position as an independent researcher. The main conclusion was that the armed forces had used structural and extreme violence and that the government had looked the other way. The terms “structural” and “extreme violence” did away, once and for all, with the idea that there were only “excesses”, as was suggested still in the Excessennota in 1969. The most important thing about these conclusions is therefore, in my opinion, that a large group of historians now fully accept the gravity of widespread violence, which will, I hope, have repercussions in the culture of remembrance and in education. This is still necessary in the Netherlands, where some groups continue to rake up the old perspectives.

A large group of historians now fully accept the gravity of widespread violence, which will, I hope, have repercussions in the culture of remembrance and in education

At the same time, however, the discussion quickly arose about the term “war crimes”, which was missing from the main conclusions. As a result, several experts and critics, including myself, consider that the idea that the Netherlands was not guilty of war crimes and that other countries were has still not been dealt with clearly enough. The euphemistic use of the word “excess” in 1969 was supposed not only to cover up the structural nature of the violence, but also to prevent comparison with German and Japanese war crimes. The fact that the Dutch authorities have also evaded responsibility for these crimes for so long and on all sides, as is well illustrated in Maurice Swirc’s book The Indish cover-up (De Indische doofpot, Arbeiderspers, 2022), makes it even more unpalatable. Using a term like “war crimes” would have brought the issues of liability and responsibility into the foreground and shifted it to politicians, such as popular former Prime Minister Willem Drees, Louis Beel and Huib van Mook.

It is striking that one of the project leaders, Frank van Vree, admitted in the radio programme OVT,

just three days after the publication of the results, that war crimes should indeed have been mentioned in the final conclusions, and that another project director, Gert Oostindie, spoke in a work from 2015 of possibly tens of thousands of war crimes committed on a structural basis, but now stated otherwise.

In contrast, the Belgian experts’ conclusions state that colonial violence originates from a colonial system and is, at its core, about exploitation and racism, which they emphasise with the term “systematic” i.e. policy based. Expert Anne Wetsi Mpoma wants to designate colonialism as a crime as well. According to Gillian Mathys, one of the experts who worked on the Belgian synthesis that was drawn up for the commission in October 2021, the experts struggled with the tensions between academic and legal interpretations of atrocity crimes. They particularly wanted to emphasise “that all the violence was systematic, and therefore a fundamental and intentional part of the colonial system, and not incidental or the result of individual excesses”. Regarding responsibility, therefore, they point to the whole period, the Church, the state and the royal family, as well as the trading companies. In De strijd om Bali (The Battle for Bali), I fully subscribe to the Belgian conclusion that violence was inherent to the colonial system, which is why my book starts in 1846. However, I consulted former lawyer Victor Koppe and legal philosopher Wouter Veraart and, as far as they are concerned, the concurrent use of “war crimes” or even “crimes against humanity” for the situation in Indonesia, is not at odds with this. The systematic character of the violence was already anchored in language by officials such as “liquidation” and “elimination” of the resistance.

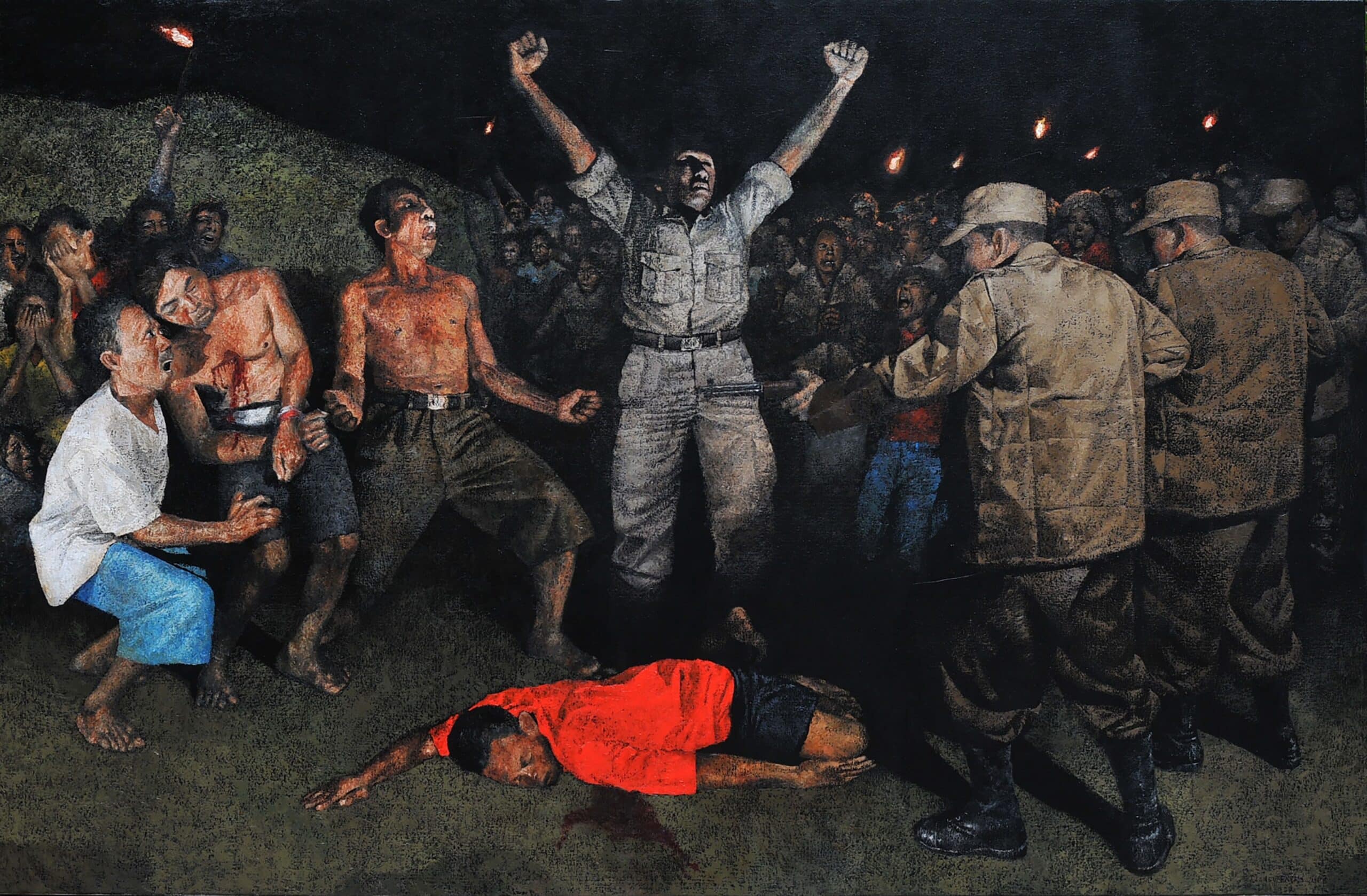

In the painting 'Eksekusi Letda Reta', Balinese artist Mangu Putra depicts his uncle's execution in 1946.

In the painting 'Eksekusi Letda Reta', Balinese artist Mangu Putra depicts his uncle's execution in 1946.© Mangu Putra

Reconciliation: genuine commitment

The Dutch government, unlike the Belgian made official apologies. Prime Minister Mark Rutte did that a few hours after the results of the Dutch study were published. However, it all happened so fast that it looked more like his umpteenth press conference than a carefully considered attempt at reconciliation with Indonesia. The Indonesian journalist Feba Sukmana, for instance, wondered despairingly during the previously mentioned radio broadcast why no apologies were offered for the entire colonial past, the exploitation, the oppression, the racism and the Cultural System. Likewise, the state once again dodged the question of whether it sees this violence as war crimes.

In the Netherlands, possible political steps such as reparations for Indonesia and the Indonesian and Moluccan communities are still unclear at the time of writing (early June 2022). (1) What was striking was that the Foreign Affairs commission roundtable discussions on the study, which were held with Dutch interest groups, mainly gave the impression that the divisions already existing in the societal debate had become wider rather than narrower. In Belgium, the commission has started to open up colonial archives and make financial resources available to African communities. (2) A commission has been set up to “decolonise” public spaces in Brussels, and legislation and a commission consisting of Congolese and Belgians has been set up for the return of looted art. Opinions are still divided on financial reparations. On 20 June 2022, decades after Patrice Lumumba’s murder, the Belgian Prime Minister finally returned his tooth to his descendants.

Reconciliation requires generous gestures, as well, such as attending commemorations and independence anniversaries (the Netherlands, incidentally, has never fully recognised 17 August 1945 as the date of independence of the Republic of Indonesia). Heartfelt words are part of this. The Belgian King Philippe demonstrated that. In contrast to his predecessors, he expressed his regret to Congo and the Congolese diaspora. He did so first in 2020, at the commemoration of sixty years of Congolese independence, the same year in which the Dutch King Willem-Alexander apologised for excessive violence during the Indonesian War of Independence.

The sincere commitment that the Belgian King showed remains absent in the Netherlands

The regrets expressed by the Belgian King may not have been an official apology, but he did intrinsically outdo King Willem-Alexander. He wrote a letter to the Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi acknowledging the suffering of the entire colonial period, as well as the impact that the colonial past has on society today. “He showed that it did not stop with decolonisation. That, for a lot of people, was a very important acknowledgement”, according to Nadia Nsayi. On 8 June 2022, during a visit to Congo to celebrate Congolese independence, King Philippe went a step further by naming colonialism as racist and paternalistic. It is this explicit condemnation of the colonial project that was missing from Prime Minister Rutte’s apology. Again and again, the sincere commitment that the Belgian King showed remains absent in the Netherlands. (3) It is to be hoped that the Dutch government may still come up with a political statement that goes further than a correction of 1969. So, the Dutch self-investigation, like the Belgian one, is not the final destination but a step forward in an important social process.