Godfried Bomans: Chronicler of a Changing Catholicism

Godfried Bomans died on 22 December 1971, but he did not really disappear. The charismatic Dutch author, who in his relatively short life amassed a large and varied oeuvre, is still read, and his tall figure is etched into the memories of many Dutch and Flemish people – like a monument.

That statue symbolises a series of contrary qualities: style, courtesy, rudeness, irony, traditionalism, humour, Catholicism, philosophy, melancholy, nostalgia, nuance, romanticism, realism, homeliness, sensitivity, egocentricity. And meanwhile we can also add loneliness. With all these attributes, it seems Godfried Bomans is difficult to grasp several decades after his death, though people like to think they know him.

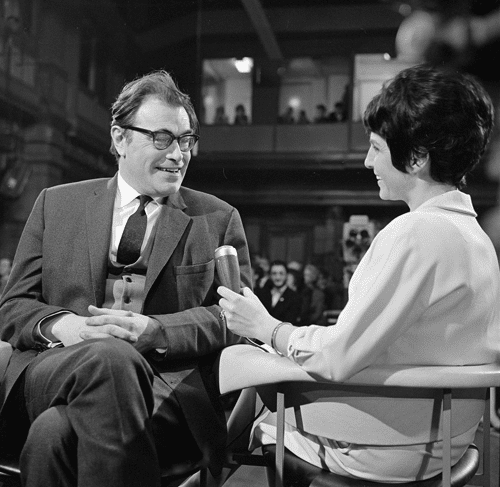

Godfried Bomans, interviewed on television by Mies Bouwman

Godfried Bomans, interviewed on television by Mies BouwmanBorn in 1913 in The Hague, Bomans grew up in a well-to-do family. His childhood and adolescent years played out in the heyday of the Roman Catholic faith when daily life was lavishly sprinkled with holy water. The Bomans family was an exponent of this religion, which the young Godfried felt ambivalent towards. On the one hand he was sensitive to the atmosphere and finery of Catholicism, on the other hand the associated dogmas instilled a crushing fear in him. Hell, Heaven and Purgatory. Everyday sin and mortal sin. Thinking about these things often kept him awake at night. He also felt burdened by the name his parents had given him, Godfried, with that weighty “God” in it. He would rather have been called Fred.

He experienced his parents as distant. He later portrayed his father, a lawyer and politician, as an unapproachable stranger with whom any form of normal communication seemed impossible. He wrote little about his mother, but she too offered him little warmth and kept her distance. Godfried Bomans grew up in an environment that offered him every conceivable material comfort, that infused daily life with prayer and holy masses, but in which affection was rarely given. The young Godfried begged for attention and warmth.

In his first works he already wielded the weapons of humour, irony, and nonsense, which he deployed against an essentially inhospitable world. Pieter Bas appeared in 1937, Erik of het klein insectenboek (translated as ‘Eric in the Land of the Insects’) in 1941. These were years when the world was turbulent and on fire. A world that would never be the same after 1945.

After an initial rebuilding of times past in the fifties, which have now been somewhat too harshly archived as oppressive and dull, the sixties caught ablaze. Left-leaning young people tugged so heavily at the tablecloths of neat bourgeois society that its tea lights, biscuit tins and the “right-wing” newspapers of authoritarian father figures ended up on the floor. Everything had to change. Words like “tradition” and “conservative” became an affront.

Before that great social upheaval, a fresh wind had already started to stir in the Catholic Church. Convening the Second Vatican Council, Pope John XXIII initiated reforms in a faith that had been deadlocked for centuries. But in everyday life, the breeze that he advocated, fuelled certainly in the Netherlands by the revolutionary zeitgeist, grew into a strong wind that often took on a hurricane force. Unshakeable truths and expressions of faith turned out to be less shock-resistant than had been thought, and Gregorian chants were replaced with committed protest songs by Bob Dylan and Joan Baez.

Godfried Bomans did not live to see the results of these modernisations; he died in the midst of this tumult that rattled the foundations of his Catholic existence.

Dominating, directing

The changing tide in the Netherlands and Flanders actually contributed to Bomans’ status, who in an atmosphere of confusion, compassion, wonder, displacement and liberation reported his observations on the developments in his inimitable way – ironically and thoughtfully. He did this not only in his short pieces in the Volkskrant newspaper, which we would now call columns. From around 1960 he was regularly seen on screen; the programme Hou je aan je woord (Keep your word) had made him a television personality that added to his renown as a writer. In that programme, North and South came together: the Flemish Karel Jonckheere presided over a select group of writers, who all played around ingeniously with the Dutch language. Harry Mulisch was there, Hella Haasse, and Victor van Vriesland, with Bomans at the centre.

His contribution was noticeably greater than that of more highly rated literary authors such as Mulisch and Haasse. They were clearly still not at ease on camera. Bomans, on the other hand, made somersaults in the language, came out with successful and less successful words of wisdom, cracked jokes and invented limericks. The live audience slapped their knees, the viewers at home were entertained. Virtually everyone that watched television in the Netherlands witnessed Bomans’ jokes and antics. In those days there was only one network, but in the border regions the channels of neighbouring countries could also be picked up. Thus Flemish viewers discovered Bomans as a television star and were similarly charmed.

His status grew rapidly the more he showed his face. In 1963 he presented the Grand gala du disque, a programme in which he awarded ‘Edisons’ to artists for their achievements. It became a festive broadcast with a touch of dinginess. Celebrated singers like Corry Brokken and the teenage star Françoise Hardy were used as a target for his jokes and the great Marlène Dietrich, visibly bewildered, had to endure a dubious speech. There were differing views among the public about Bomans’ Edison awards, but his performance gained near-legendary status over time.

'If only my wife had one leg like that', Bomans joked in his introduction to Marlène Dietrich on television

The joke that Bomans made in his introduction to Dietrich – “If only my wife had one leg like that” – has been replayed over and over and is, in terms of image and text, etched in many memories. The same goes for other appearances: excerpts from Hou je aan je woord (Keep your word) are regularly dusted off and replayed as well. In all those clips you see a Bomans in his element. He enjoyed performing, being in the spotlight, audience at his feet laughing and clapping. The response was immediate, ego-stroking and left him wanting more. Television had discovered him and he had discovered television.

Bomans wanted to dominate, direct, be loved and liked. That need for attention was constant; his television appearances show him posing, exaggerating, and eager to please. He understood the possibilities of the medium early on and exploited them in his own way – presenting as a jack-of-all-trades: entertainer, cabaret artist, stand-up comedian, clown, philosopher. With a perfect sense of timing, he performed clumsiness, absent-mindedness, half-mumbled casual asides, managing to elicit laughter from the audience time and again. When interviewed himself, he knew how to make the interviewer almost invisible, or at most no more than a prompter for his compelling phrases and witticisms. On television, he built up an empire of devoted followers.

The period in which Godfried Bomans dedicated himself fully to television is regarded as the demise of his authorship. Apart from journalistic contributions, bulletins and some occasional assignments, his hands penned nothing more substantial. As Bomans had in his early days produced exceptionally strong work – Pieter Bas, Erik, Sprookjes (Fairytales) – unfortunately for him, this meant that his readers expected new books that were at least as good. However, it is not fair to dismiss his television work as just easy money. Much of his screen performances were expressions of narcissism, but he made television history by being himself.

Bomans the television star lives on in the collective Dutch and Flemish memory at least as much as Bomans the writer. Certain clips of his performances have been elevated to the status of a standalone sketch, thanks to their numerous replays. Few writers have so many images of themselves embedded in public memory. The fact that he was a writer too in the end was by the by.

The old gone, the new not yet underway

In Dutch and Flemish homes Bomans was seen as a pleasant guest who transcended the border between North and South, always remained polite and was a bit naughty. Precisely during the period of shifting norms and values, Bomans remained a recognisable solid institution. There was revolt, there were happenings and demonstrations – against the Vietnam war, for example – but it was all championed by a progressive vanguard, which would only gain broader public support much later.

The vast majority of the Netherlands and Flanders remained conventional. For these people Bomans was the symbol of an orderly “bourgeois” society, especially at a time when many were considered to be on the rampage. His humour was provocative, but never crude. Bomans thereby reached a wide audience; in a still compartmentalised society he, the Catholic, was not picky and he also performed for other broadcasting stations like AVRO and NCRV.

The progressives, especially the young, perceived him differently. They saw a complacent gentleman who wanted to be fun all the time and laughed at his own sometimes stupid jokes. A gentleman who spoke a bit posh – and, a mortal sin in those days, had conservative views. His pieces in the Volkskrant were seen as reactionary and occasionally provoked strong reactions in circles of De Rode Jeugd (Red Youth).

The romance of Catholic life, which had glittered so grandiosely, was stripped down, in the Netherlands slightly more zealously than in Flanders.

But Bomans’ outlook was not frozen in time. In particular, the shifts in the institution that had coloured his life from his earliest childhood, from warm red to inky black, affected him emotionally. Amazed and engaged, he observed the changes in “his” church, watched how newly redundant confessionals were dismantled, listened to sermons on oppression and solidarity, pityingly observed the priests wearing gloomy turtlenecks and the nuns in unflattering suits, came across the bruised plaster casts of Saints Agnes and Antonius at a flea market. The romance of Catholic life, which had glittered so grandiosely, was stripped down, in the Netherlands slightly more zealously than in Flanders.

Bomans saw that a cultural era was rapidly coming to an end. While rationally he could accept that, it hurt his feelings. With the dismantling of all pomp and circumstance, the atmosphere of his youth was also discarded. He hurriedly set down a number of striking characteristics from his Catholic past on paper, collected in 1970 in Beminde gelovigen (Beloved believers).

The old has gone, the new has no clear form yet, he stated. He was well aware that nostalgia could strike in the face of all reason, but he also knew that this was a longing for the atmosphere of a lost childhood. Those who looked back soberly knew, however: “We lived in a complacency rooted in fear.” It was an aphorism that many Catholic Dutch and Flemish people recognised.

In 1969, together with the Catholic writer Michel van der Plas, he published In de kou (In the cold), the result of a series of conversations they had had about their Catholic childhoods, the changes and the future, in which their children would live with less certainty and less mysticism. Bomans saw a new world emerging, in which things simply referred to themselves, with no double meanings. He knew that longing for the homely warmth of “the past” was no longer an option. Everyone had grown up.

His articles and stories about the church of his youth have attained the status of a true cultural monument

Bomans thus came to symbolise the entire development in the Catholic Church. He personified the safe but defeated past, the liberating though simultaneously confusing present and an as yet unclear future. Many years after his death, now that Catholic life is on the verge of beggarhood and few beloved believers are left, his articles and stories about the church of his youth have attained the status of a true cultural monument.

For the television programme Bomans in triplo (1970), Bomans travelled to the monasteries where his sister Wally and brother Arnold were Sister and Father, respectively, and talked to them about their youth, duties, faith, and the survival of religion and monastery, which was threatened by the erosion of Catholicism and the decline in those seeking vocation. In the Netherlands and Flanders, people were moved by this much-talked-about show, in which a mildly philosophizing Bomans took a restrained position and made no attempt to make people laugh.

He showed his best, earnest side. A side that was not new, but had until then mostly been masked by mockery. Pared back to the essential, Bomans walked with his sister and brother in the relics of an almost vanished world. Bomans in triplo became a subdued memorial of traditional monastic life, as it had flourished, especially to the south of the big rivers. These were the last convulsions of a Catholicism, as it had been depicted particularly in the works of older Flemish writers such as Ernest Claes and Felix Timmermans.

Thinking of Flanders

Bomans has written extensively about Belgium and Flanders. In 1967 he wrote a series of articles for Elsevier, ‘Denkend aan Vlaanderen’ (Thinking of Flanders), about the place that endeared and amazed him. From a rather generalising point of departure, thinking in terms of “us” and “them”, he arrived at various, not always flattering, characterisations of Flanders and the Flemish. He described “the” Flemish student’s distinctive timidity, compared the interior of the typical Flemish living room to a funfair, observed a complete lack of pathos in the neighbouring people and believed that there were more eccentrics than in the Netherlands. On the other hand, he openly declared his love for the warm, melodic language and Flemish tolerance – and the pubs in Flanders he liked to visit.

Four years later, in the spring of 1971, Bomans spent twelve days in Belgium, where he conducted interviews for the television series Een Hollander ontdekt Vlaanderen (A Dutchman discovers Flanders). The somewhat joking tone of a few years earlier had disappeared. The Netherlands had been adrift for several years and Bomans saw his country changing. From this environment, in which everything was in motion, he approached Flanders as a safe fortress with much that was precious.

The questions he asked and his reflections on the answers of the interviewees show an unwavering love for “this blessed land”, which for him harboured greater intimacy and warmth than the Netherlands. For him, everything felt “warmer” just south of the Moerdijk bridge and in his interviews, he pronounced his love for the village water pumps and pubs, which appealed to his need for cosiness. He again paid tribute to the Flemish accent he found so lovely and the richness of language with its beautiful archaisms. He further praised the Flemish for their kindness, tolerance, and respect for other people’s opinions, where the Dutch were generally annoyingly direct and explicit.

Bomans never really felt at home in his own time, and the disappearance of specific Catholic cultural expressions reinforced that

Bomans never really felt at home in his own time, and the disappearance of specific Catholic cultural expressions reinforced that. He was a romantic, astray in the here and now. Just as the child Godfried yearned for another name, the grown-up Bomans sought escape routes to make life enjoyable. His fairy tales and humour provided a solution. The cosiness of the Biedermeier era, Dickens’s time, had more appeal for him than the time of apartment buildings and passenger planes. He was under the illusion that Flanders, more than the Netherlands, had retained something of an atmosphere dear to him.

But during his visit in 1971 he had to recognise that Flanders had also grown up – stripped back, Bomans wrote. The land of Ernest Claes and Felix Timmermans had become part of the land of Hugo Claus and Louis Paul Boon. Lode Craeybeckx, mayor of Antwerp in 1971, later said that he had the impression that Bomans had been somewhat disappointed when he travelled through Flanders. He had hoped to locate something of the rustic, idyllic Flanders, but was forced to conclude that life had moved on south of the rivers. Pastoor Campens zaliger (Pastor Campens fondly remembered), a title by Ernest Claes, had taken on a symbolic charge.

Alone on Rottumerplaat island

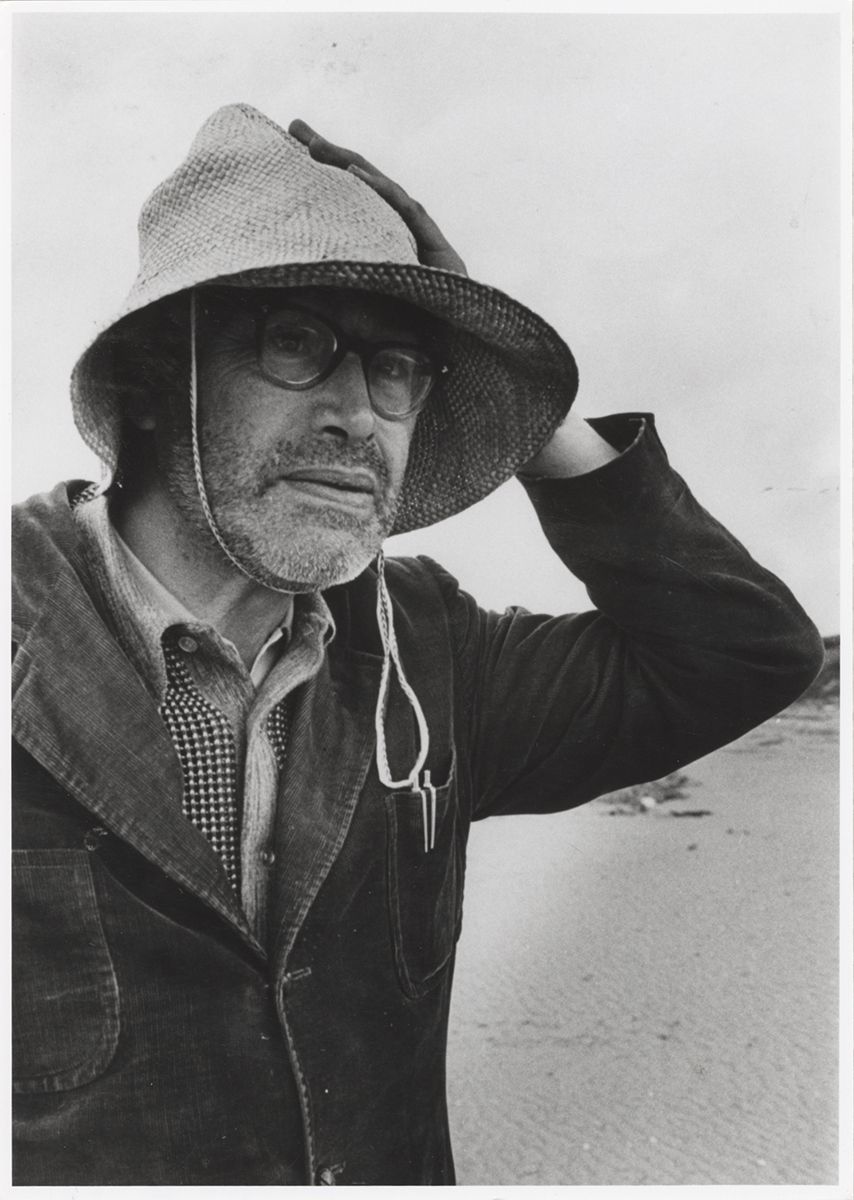

Bomans’ image was again supplemented and changed when, in the summer of 1971, he accepted an invitation from AVRO and VARA to stay on the island of Rottumerplaat in the North Sea. Again it was television that made an essential contribution to the memory Bomans would leave behind. Viewers encountered a vulnerable, dejected, suddenly aged man, who felt miserable on the island, with no people, separated from civilization by water with only screeching seagulls that frightened him for company. For the first time in a very long time, he was alone, without other people to make him sparkle, without an audience applauding him.

Thrown back on himself – but who was he? Could he still find himself among all the roles he had played? The sublime writer. The joker. The roguish presenter. The would-be Saint Nicholas. The stand-up comedian. The Catholic. The restless husband and father. The organiser of confusing games and practical jokes, of which his friends – did he actually have any? – had been the target so many times. On the lonely Rottumerplaat island, Bomans slid from introspection into depression, which, it seemed, eventually resulted in a tentative catharsis. He thought a lot about the past and, he wrote in his diary, only now saw who he was, understood how he had come to be so and that it had to be like this. “That’s how it all turned out and I’m healing from my wounds.”

Bomans at Rottumerplaat

Bomans at RottumerplaatⒸ Literatuurmuseum Den Haag

He did not get much time to allow this insight to sink in, because half a year after Rottumerplaat he died unexpectedly. His stay on the island thus became legendary for many. The Bomans of that time as he was seen on film and in photographs – tired, worried, desolate – was unfamiliar and already seemed in the grip of his impending death. Thereafter it was said: he had had such a hard time on Rottumerplaat that he succumbed. The Rottumerplaat myth still feeds the imagination: in 2008 a theatre performance about Bomans’ island adventure was staged on the nearby island of Terschelling.

More mystery

Bomans entered the grave as the melancholy philosophizing, carefully formulating storyteller who had enlivened society with his fairy tales, humour, and fantasy. A man with a penchant for cosiness and homeliness, with whom many identified but who for others symbolised a small-minded and bygone era. During his funeral, people crowded around the cemetery, so as not to miss anything of the macabre event.

The sheer amount of attention was a prelude to the years that followed, when Bomans continued to enjoy intense interest from a large audience. His reputation turned posthumously when it became known that he had been with other women while married. This information reinforced the image of the lonely Bomans, as had been seen on the uninhabited island, and also made him more puzzling: who had Bomans, outwardly appearing so normative and noble, been in reality? Because of his frequent television appearances, people thought they knew him, but now it transpired that he had also other unknown sides to him. As more anecdotes about him surfaced – about his egocentricity, his need to disrupt people and situations, his loneliness – the mystery of his person grew.

The appreciation of Bomans as a writer has remained fairly constant, but it can nevertheless be said that for many young people in the Netherlands and Belgium he is a forgotten author. The same applies, of course, to other writers who have been dead for years and, like Bomans, represent another world, an era past its sell-by-date. For Bomans in particular, his careful, somewhat baroque language use is far removed from the current “fast” colloquialism and his cautious, balanced judgments is out of tune with the often-fierce positions of our time.

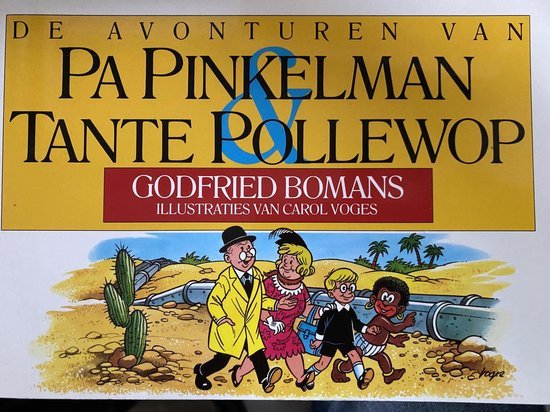

His humour, especially in his early work, seems quaint to the modern reader, and his themes – Catholicism! – have become slightly dated. Nevertheless, in June 2008, in response to a theatre show about his popular comic strip heroes Pa Pinkelman and Tante Pollewop, it was written: “His work is difficult to categorise, but he was certainly a great stylist. Bomans’ work is characterised by versatility, a great sense of humour and indestructible irony.”

The same qualities characterised his appearances on television. Anyone looking at old images of Bomans in the current atmosphere of hardened social and political debate will be overcome by a sense of nostalgia. A longing for nuanced commentary that provides perspective, delivered in a somewhat wordy, but above all beautiful and subtly ironic use of language, which was so appreciated both in Flanders and the Netherlands.