How Even William the Silent Could Not Hold the Netherlands Together

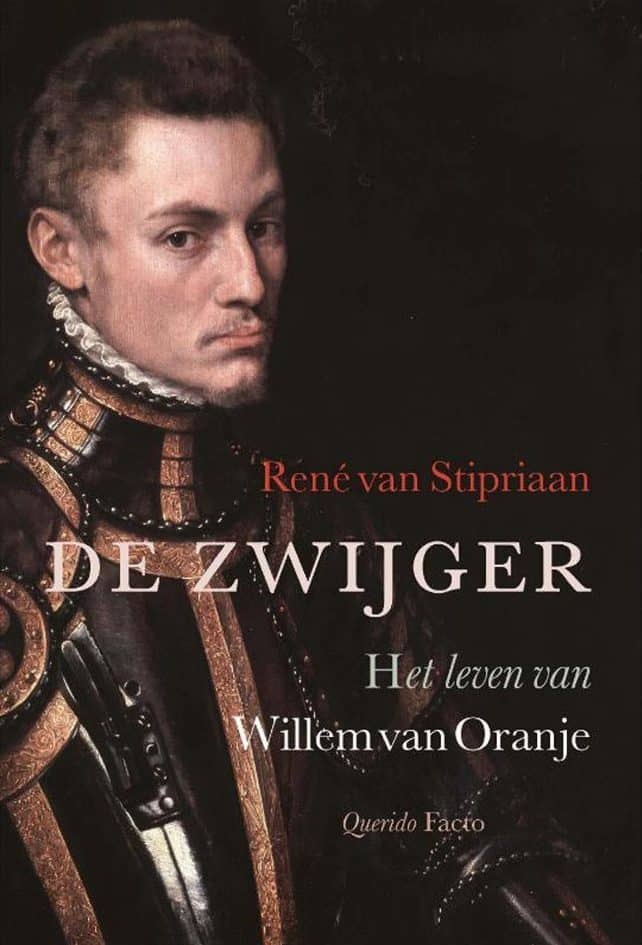

Last year, cultural historian René van Stipriaan’s long-awaited book about William of Orange, Father of the Dutch Nation, was published: De Zwijger. Het leven van Willem van Oranje (The Silent. The Life of William of Orange). During the height of his power, it seemed that Orange would become the Father of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, of north and south. Quite why this did not happen at the end of that turbulent sixteenth century is outlined by Van Stipriaan in this exclusive piece for The Low Countries.

On 30 January 1648, European powers signed a peace accord in Münster in which the Republic, consisting of seven independent northern Dutch regions, was recognised as a sovereign state. With this, the rift between north and south in the Netherlands was formally ratified. This rupture had already been inevitable for some time and, as time has told, was definitive. The short period after the Napoleonic Wars, from 1815, during which both regions united under one (Northern Dutch) monarch, was not a success. In the summer of 1830, a revolution began in Brussels that resulted in the establishment of an independent Belgium after only a few months.

The Ratification of the Treaty of Münster in 1648, painting by Gerard ter Borch.

The Ratification of the Treaty of Münster in 1648, painting by Gerard ter Borch.© Rijksmuseum

Quite apart from the question of whether this in itself is regrettable, it is clear that both Belgium and the Netherlands have become progressive and prosperous nations since 1830 that have never since engaged in a mutual armed conflict and that even cooperate well with each other. People sometimes dream of a reunification of the two countries, such as the mayor of Antwerp, Bart De Wever, for instance, in the summer of 2021. De Wever was referring explicitly to Flanders, however, and not to Belgium, which he suggested should only seek to collaborate more closely with the Netherlands in future. This “Flemish” caveat makes it immediately clear how people develop their own projections when thinking of the Netherlands, irrespective of whether they are united or not.

How do we arrive at the idea of a United Kingdom of the Netherlands?

Yet, how do we arrive at the idea of a United Kingdom of the Netherlands? And what caused the different regions to drift apart? Was it preventable? And, if so, who held the key? Many lines trace back to the early years of the Revolt, during which William of Orange (1533-1584) forged an alliance of nobles, merchants and preachers, who fought against the sovereign authority of the Spanish king, Philip II. For a long time, Orange seemed capable of bringing together the various rebellious regions in an unprecedented alliance. What precisely his role in this collaboration was and what he thought about the future of the Netherlands is a story to be told in five episodes.

Philip II, King of Spain, Reproaches William I, Prince of Orange, in Vlissingen upon his Departure from the Netherlands in 1559. Painting by Cornelis Kruseman, 1832

Philip II, King of Spain, Reproaches William I, Prince of Orange, in Vlissingen upon his Departure from the Netherlands in 1559. Painting by Cornelis Kruseman, 1832© Rijksmuseum

Episode 1: peace – it has promise

At the beginning of the Revolt, the mutually united and independent Netherlands were a fairly new phenomenon. In the late Middle Ages, the delta of the Rhine, Meuse and Scheldt consisted of an archipelago of counties and duchies that were more likely to wage war with one another than to seek out cooperative alliances. From the beginning of the fifteenth century, the Burgundian lords, who were gaining control over an increasing number of these provinces, encountered great difficulty in pacifying this region.

© Wikimedia Commons

Born in Ghent – and perhaps for that reason still feeling a connection to the Netherlands – sovereign lord Charles V of the Habsburg House finally forced a far-reaching integration of the Dutch provinces into an independent Burgundian Circle (regional group of states) at the Diet of Augsburg in 1548. The older ties of different provinces – such as that between Gelre, Utrecht and Overijssel with the Holy Roman Empire, or Flanders with France, for example – were loosened as much as possible. As a result, the internal cohesion between the seventeen provinces – from Artesia and Luxembourg in the south to Groningen and Friesland in the north – was potentially greatly strengthened.

What Charles likely had in mind was a strong, prosperous buffer state that could help keep his arch-enemy France from intervening in the Holy Roman Empire. Stubborn princes, and not to forget Martin Luther, were already presenting him with enough challenges there in his capacity as emperor.

The seventeen provinces, however, had little more in common than their geographical proximity and had been used to running their own affairs for centuries. Attempts by Charles V to forge them into a more administratively and economically unified whole were largely unsuccessful. The provinces attempted to hold on to their rights for as long as possible, which were often laid down in so-called privileges. These privileges, such as tax exemptions, control over infrastructures etc., often constituted competitive advantages over other regions. In this way, Dutch provinces were more frequently competitors than allies.

Philip II of Spain, painted by Sofonisba Anguissola in 1573.

Philip II of Spain, painted by Sofonisba Anguissola in 1573.© Wikimedia Commons

In 1555, Philip II took over the sovereign authority of the Netherlands from his father Charles V and continued the efforts to forge the Netherlands into a unity. In practice, a unified government also meant increased power for Philip himself as the ruler, who had far-reaching absolutist aspirations. Philip’s will should ultimately prevail everywhere. In order to achieve this aim, he drew increasingly more intensively on the services of seasoned jurists such as Granvelle and Viglius, who, especially from 1560, made attempts to rein in regional aspirations.

Philip did not want to be seen to make a single concession to Protestant movements such as the Anabaptists and the Calvinists

The prominent position of a born organiser such as Granvelle within the state enterprise came at the expense of the authority that high nobles, such as William of Orange, Lamoraal van Egmond and Philip van Horne, believed was theirs to claim. A conflict began to smoulder. This could have fizzled out with a little massaging from Philip II but he was determined to push through his absolutist agenda by any means necessary. Meanwhile, he entered into another serious conflict with the cities and provinces about tax payments and attempted once again to convert old local rights into new central regulations. In retrospect this was a necessary modernisation, but it touched upon the pride and economic interests at the heart of the wealthy merchant classes in particular. Moreover, Philip did not want to be seen to make a single concession to Protestant movements such as the Anabaptists and the Calvinists. They were arch heretics in the eyes of the devoutly Catholic Philip II: on that point there could be no compromises. The Calvinists in particular developed into militant fighters for their faith from 1560.

Episode 2: do not come for our rights, our beliefs, our interests

It was this mixture of anti-absolutist, anti-Roman Catholic and also anti-Habsburg sentiment that sought a way out in 1566; first in a thinly veiled conspiracy of protesting nobles and, shortly after, in hedge preaching and the Iconoclastic Fury. William of Orange (1533-1584) was the richest and most important nobleman of the Low Countries, he was stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht and also the most important noble in Brabant. Moreover, at least nominally, he was the first adviser to regent Margaret of Parma. In these tumultous months, William of Orange remained the focus of attention. What was he going to do? Did he dare to defy the regent and Philip II?

William of Orange, painted by Anthonie Mor around 1554.

William of Orange, painted by Anthonie Mor around 1554.© Wikimedia Commons

The inconvenient truth at this time for Orange was that the Spanish king and his chief confidents had known for years that Orange was pursuing his own ambitious agenda to reduce the power of the Habsburgs in the Low Countries and, concomitantly, to increase the power of the native nobility, which included almost certainly his own. Although peace had largely returned by the end of 1566, Philip II decided to send his most important and notoriously heavy-handed general to the Netherlands: The Duke of Alva. Orange realised that it was wise to relocate to the familial castle, the Dillenburg, deep in the German Reich. Shortly after, his possessions were confiscated by the Spanish government in absentia.

From that moment forth, Orange fought openly against the Habsburg regime; initially with very little success. He ran himself into great debt after two failed campaigns in 1568 and 1572 and lost all creditworthiness. By the summer of 1572, Orange was thus not only robbed of virtually all his possessions and heavily burdened with debt but, even worse, he had lost all credibility with friend and foe. In the meantime, Alva had been able to bend events to his will through tremendous displays of military strength. Hundreds of people were summoned before a special court: the Council of Troubles, which was soon nicknamed the Council of Blood. Those summoned to the council were often made to forfeit their assets before being sentenced to death.

The Duke of Alva presides over the Council of Troubles.

The Duke of Alva presides over the Council of Troubles.© Wikimedia Commons

Episode 3: Orange in Holland

Without hoping for miracles, William of Orange travelled to Enkhuizen in Holland in October 1572, where several cities had revolted in the past six months. He relayed to his brother Jan rather dejectedly that he expected to “find his grave there”. Here, Orange allied himself with Holland – the jovial nobleman, whose most important and expropriated possessions were mainly in Brabant, now had to deal with frugal and calculating Dutch merchants and city administrators. At first sight, quite a different set of folk than those people from Brabant and Flanders. Dutch merchants often travelled on sea voyages themselves – they were more like transporters than traders. The south was much more oppulent; Flanders in particular had a flourishing industry in luxury products, and the Brabantine Antwerp had grown in the last half century into a trading city where almost everything was for sale and the whole world came to do business.

In the years following 1572, the struggle played out primarily in Holland and Zeeland. The imaginative battles for cities such as Den Briel, Vlissingen, Haarlem, Alkmaar and Leiden strengthened the position of Orange as the leader of the Revolt. In Holland and Zeeland, Orange became the connecting link between his local allies. In this position, he made use of the network of well-disposed administrators that he had built up long before 1566 as the governor of the king.

Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, the Duke of Alva, painted by Anthonie Mor in 1549.

Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, the Duke of Alva, painted by Anthonie Mor in 1549.© Wikimedia Commons

Alva was run aground by these two rebellious provinces. His last strong bridgeheads – Amsterdam, Haarlem and Middleburg – also threatened to fall into the hands of the rebels in the not-too-distant future. New tax measures, such as the introduction of the Tenth Penning, made Alva very unpopular across the Netherlands. After running into financial difficulties, Alva lost the confidence of Philip II. His successors Requesens and Don Juan did not fare much better.

After a lengthy siege in the summer of 1576, the Spanish army reconquered Zierikzee and appeared to be regaining control of the situation. But things took a turn for the worse for the Spanish government. The underpaid army mutinied, advanced towards Flanders and plundered Aalst, before thundering into Antwerp, where enormous devastation was wrought. This ‘Spanish Fury’ led to a collective trauma in Antwerp and the distaste for the Spanish troops and the regime that Philip II had organised became commonplace throughout the Netherlands. Alongside Holland and Zeeland, all other provinces began to revolt. The Spanish troops had to leave the country.

The Spanish Fury, anonymous, ca 1585, MAS, Antwerp

The Spanish Fury, anonymous, ca 1585, MAS, Antwerp© Wikipedia

Episode 4: Orange’s ‘Finest Hour’

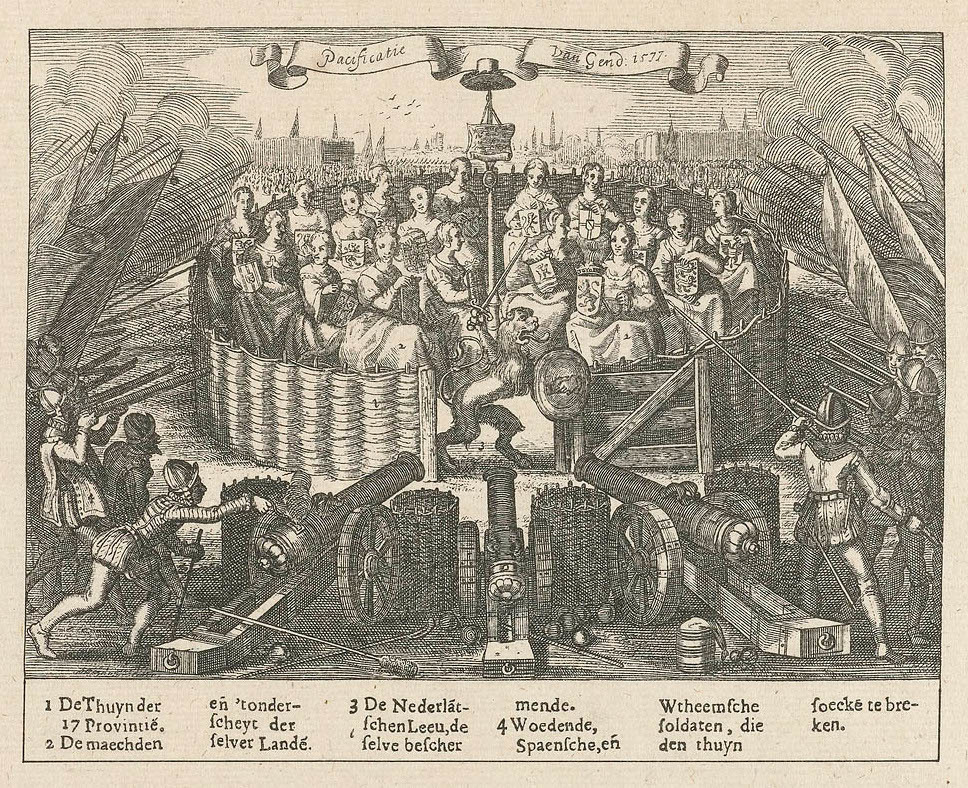

This demand was ratified across all provinces in the Pacification of Ghent in November 1576. Orange was quite clearly the orchestrator of this display of Dutch unity. He had proven his political intuition in the months preceding through his flawlessly anticipated diplomacy and propaganda. Indeed, Orange had long since been fanning the flames of the anti-Spanish sentiment by widely disseminating rather unnuanced printed matter, while allowing his officers to work on the spirits of the Brabant and Flemish cities in the meantime.

Reproduction of the allegory on the Pacification of Ghent, 1576, after Adriaen Pietersz. van de Venne

Reproduction of the allegory on the Pacification of Ghent, 1576, after Adriaen Pietersz. van de Venne© Wikimedia Commons

During the Pacification everything fell into place; Orange was now considered in both north and south to be the absolute leader of the anti-Spanish resistance. This triumph, however, was soon to be spoiled. In the years prior to the Pacification, the Calvinists had often been Orange’s most tenacious allies and had since moulded religious life in Holland and Zeeland to their will. The Calvinists now demanded space to practice their religion in other provinces too and, when Orange allowed it through a religious peace accord, they immediately attempted to dominate all aspects of religious life in cities where they had a large following, such as Ghent, Bruges, Brussels and Antwerp. Orange had given them an inch…

The situation in the south became unstable; Catholic factions arose that wanted to stop the Calvinist advance, the seemingly perfect facade of the Pacification broke down. The south was plunged into a grim civil war. Orange lost control of the situation.

The first decades of the Revolt were characterised by a crisis within the central authority

The first decades of the Revolt were characterised by a crisis within the central authority. It was not only the Spanish regime that failed to bring the provinces to heel and encourage cooperation; the same fate now befell Orange. Meanwhile, he was ruling together with the States General and it proved impossible to take rational decisions quickly. Many of these ended in a sluggish unwillingness to lend support to other provinces – very recognisable for those who now look at the operation of the European Union. The longer this malaise lasted, the more cities and provinces started to follow their own agenda.

Episode 5: casual decisions

Very casually, an economically flourishing Holland began to organise a security cordon for itself. Holland became increasingly involved in the administration of the Utrecht region, concluded all kinds of treaties with Zeeland and gradually constructed a belt of fortifications in the river area. This pursuit of security was aptly described in the propaganda of the time as a fenced garden, also known as a Dutch garden.

Detail of the drawing 'Stop rooting around in my garden, Spanish pigs', 1578-1582

Detail of the drawing 'Stop rooting around in my garden, Spanish pigs', 1578-1582© Rijksmuseum

William of Orange hoped for a long time that the united Netherlands would still be able to keep the Spanish regime at bay, or at least to strip it of its military means of power, but in the meantime, he cooperated fully with Holland and Zeeland to erect barriers against any potential Spanish invasions. Thus, Heusden was annexed to Holland and converted into an imposing fortified city shortly after the Pacification of Ghent. The Brabant town of Geertruidenberg, originally owed by Orange himself, had already fallen into the hands of the rebels in 1573 and was also converted into a modern fortress. The Dutch and the Zeelanders ensured that the city continued to be supplied.

Within a few years, under the guise of ensuring more security and no doubt with the best intentions in mind, a dividing wall was erected between north and south. Orange himself added a crowning achievement to the work, when he took the initiative to build a new fortified town in 1583 in the region where he had held so many possessions – not only Geertruidenberg but also the ancestral castle of the Nassaus in Breda, which now lay in the hands of the Spanish. In the Ruigenhil polder that had been drained in the years previously, the contours of enormous defences arose within a few short months, which were intended to offer security to a city of several thousand citizens and garrison soldiers: Willemstad.

Capture of Geertruidenberg, 1573, anonymous, after Frans Hogenberg, 1613-1615

Capture of Geertruidenberg, 1573, anonymous, after Frans Hogenberg, 1613-1615© Rijksmuseum

Every invading force from the south was compelled to take increasingly large diversions and maintain increasingly long supply chains due to the line of defences that now surrounded Holland. By the time that Amsterdam crossed over into the rebel camp in 1579, it was supposed that the Spanish army would no longer pose a serious threat to Holland and Zeeland. After a decisive commander in the Spanish service, Alessandro Farnese, brought Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp to their knees in quick succession between 1584-1585, however, it became clear precisely how provisional the construction of this cordon had been.

But it was also an expression of a lack of unity – Holland and Zeeland chose quite clearly for their own interests and made very little effort to keep the south in the hands of the rebels.

And where did Orange stand in the matter? He cooperated fully in the preparations for that dividing wall. But it was against his will – he believed in the unification of all seventeen provinces of the Netherlands. When that turned out to be neither tenable nor justifiable, however, Orange must have thought that it was high time to save what could reasonably still be saved, while others were busy keeping the anti-Spanish rhetoric alive in Ghent, Bruges, Antwerp and a number of other cities in the south. At that time, it seemed that half a “free” Netherlands was still better than no Netherlands at all.

De zwijger. Het leven van Willem van Oranje (The Silent. The Life of William of Orange), Querido Facto, 2021, Amsterdam, 944 pp.