Jacob Kats, a Forgotten Fighter and Pioneer of Brussels Socialism

He was admired by Rosa Luxemburg and visited by Bakunin, Marx and Engels, yet almost no one knows his name today. Nevertheless, Jacob Kats, Brussels theatre-maker, agitator and organiser, was one of the founders of socialism in the turbulent nineteenth century. Johan Wambacq has authored a book about Kats and, here, he sketches the profile of a writer and activist who always kept the interests of the working people in his mind and heart.

Have you heard of Jacob Kats? No, not the 17th-century poet and politician from The Hague. That was Jacob Cats, with a ‘C’. We are talking about “Father Kats”, with a ‘K’, who was active in Brussels and Flanders during the 19th century. Apart from a few historians, nobody knows about him anymore, but that wasn’t always the case. Jacob Kats (1804-1886) organised political meetings throughout Flanders and was active as a publicist, satirist, playwright, director and actor. In 1902, sixteen years after his death, Rosa Luxemburg honoured him as “perhaps the most original of the international socialist pioneers, the creator of the first workers’ association, of the first democratic folk songs, of the first folk theatre in Flanders.”

Jacob Kats started working in the textile mill where his father was employed.

Jacob Kats started working in the textile mill where his father was employed.© Wikipedia

Jacob Kats was born in Antwerp on 3 May 1804. In 1808 his family moved to Lier where, at the age of six, Jacob started working in the textile mill where his father was employed. The Kats family moved to Brussels in 1819.

The Kats children were illiterate. Jacob was eighteen years old by the time he learned to read and write. From 1823 to 1827 he and his brothers attended one of the free evening schools in one of the 1,500 public schools William I set up in the southern Netherlands during his 15-year reign. Jacob eventually even became a teacher. Three years later, Belgium became independent and the public schools were abolished – the Catholic church’s “revenge” for losing its monopoly on education due to the policies of the energetic William I. In 1831 Jacob was fired from his teaching job and his diploma was declared invalid. Two years later, he was once again earning a poor living as a weaver.

The Brotherhood

In 1833, with his brothers and some other working men, Kats founded The Brotherhood. The association was set up for the – predominantly illiterate – working population, for whom it organised discussion evenings.

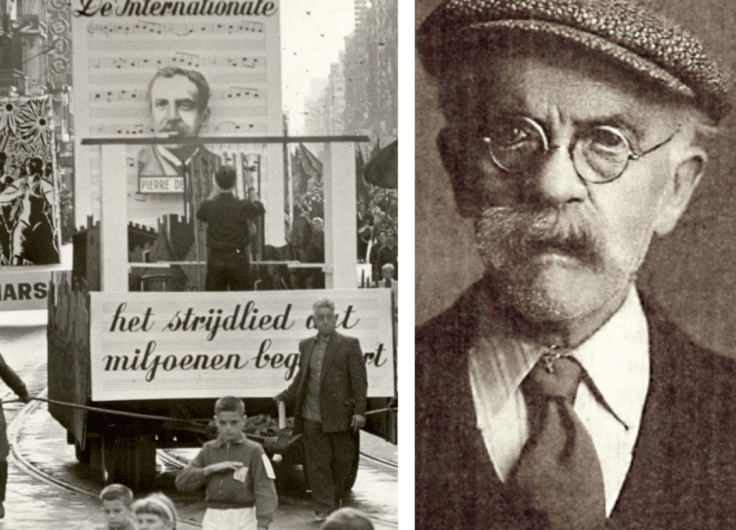

The social-Christian vision of he French priest Félicité de Lamennais inspired Jacob Kats.

The social-Christian vision of he French priest Félicité de Lamennais inspired Jacob Kats.© Wikipedia

Kats was inspired by the social-Christian vision of the French priest, writer and philosopher Félicité de Lamennais and other visionaries. He was supported – also financially – by the journalist and lawyer Lucien Jottrand, one of the key players in the Belgian revolution and later a member of the National Congress. Jottrand recognised a primal talent in Kats – the ability to inspire large groups of people.

In February 1835, Kats established a theatre group within The Brotherhood that included both men and women and, in the same year, wrote no fewer than five pieces for the troupe. Four were popular farces with pointed, political messages. The fifth piece, Het Aerdsch Paradys or Earthly Paradise, sounded a different note. It was “our first and only social Utopia”, wrote Julien Kuypers in Early Socialism to 1850.

Kats’ theatre productions attracted both large audiences and numerous police complaint reports. A bill drafted by Interior Minister Barthélémy de Theux to legalise theatre censorship was a direct retaliation against Kats and The Brotherhood.

Jacob Kats wrote theatre plays.

Jacob Kats wrote theatre plays.© Google Books

The People’s Friend

1835 was a very busy year for Kats who wrote, directed, acted and organised performances with The Brotherhood. … and as if that were not enough, he also threw himself into journalism. At the invitation of Pierre-Armand Parys, who had already published a few of Kats’ pieces, Kats brought out the satirical newspaper Uylenspiegel. And that, too, was closely monitored by the State Security service.

But Kats said goodbye to Uylenspiegel after only one year because he wanted to focus on political activism. His stage performances began to take the form of political meetings. In the run-up to the first meeting, the first issue of Kats’ own weekly magazine, Den Waren Volksvriend, later simply called Den Volksvriend or The People’s Friend, appeared. It was regarded as the “first Flemish workers’ magazine, the organ of the Flemish Meetings” and was published from June 1836 to February 1840. Some four hundred editions were probably printed, barely sixteen have survived.

The first meeting

On Thursday, 11 August 1836, the first political meeting was held in ‘t Lammeken, a café in the Hoogstraat, in the heart of Marolles. The meetings always took place in cafes. It was not long until Kats and his friends moved on to other cities: Leuven, Antwerp, Ghent, Mechelen, Kortrijk, Temse… The Brotherhood held its meetings indoors and ensured an orderly course. Order was important because sometimes the police would send rabble-rousers to the meetings to cause trouble, thereby providing an excuse for law enforcement to intervene.

During one of the meetings, a drunken police commissioner provoked an incident which resulted in Kats being detained as a preventive measure and only released more than a month later. A solidarity campaign was started to cover the costs of Kats’ trial. The call was not only heard throughout Belgium, but also in England, a clear indication that the fledgling labour movement already had international connections and Kats’ work had been making a strong impact from the start.

After having to go behind bars for the third time in 1840, Kats was financially strapped.

After another provoked incident in 1840, Kats was put behind bars for the third time. Again on 11 August, a Tuesday this time, Kats and three others were ordered to report to the prison in the Kleine Karmelietenstraat. They were escorted there by a procession of hundreds of shouting supporters. Kats is the only one who ended up having to serve a full six-month sentence. He fell into financial trouble at this point.

After a forced break lasting a few years, he resumed his meetings and theatrical performances, but at a new location: the Salon de Monplaisir, the first “people’s house” in Belgium. There, he welcomed visitors from abroad, including Mikhail Bakunin, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Karl Grün. In his work Die soziale Bewegung in Frankreich und Belgien (Socialist Movements in France and Belgium), Grün offers an extensive and enthusiastic report on his visit to the Salon de Monplaisir. Kats collaborated with Marx in the Association Démocratique Internationale (International Democratic Association) that had been founded in November 1847 by Kats, Jottrand, Marx and many others.

The violent overthrow of every existing social order, promoted by Max and Engels, contradicted the pacifist views of Jottrand and Kats

However, things did not go smoothly between chairman Jottrand and vice-chairman Marx. Marx considered “bourgeois socialism” as something for weaklings. In their Communist Manifesto, published in February 1848, Marx and Engels made it very clear that the goal of the communists “can only be achieved by the violent overthrow of every existing social order.” This approach completely contradicted the pacifist views of Jottrand and Kats. In the same month, Kats, Marx and Engels, amongst others, spoke at a meeting of the Association Démocratique. Intelligence agencies reporting on the meeting noted that Kats said that the people would have to wait to claim their rights, that the time was not yet right.

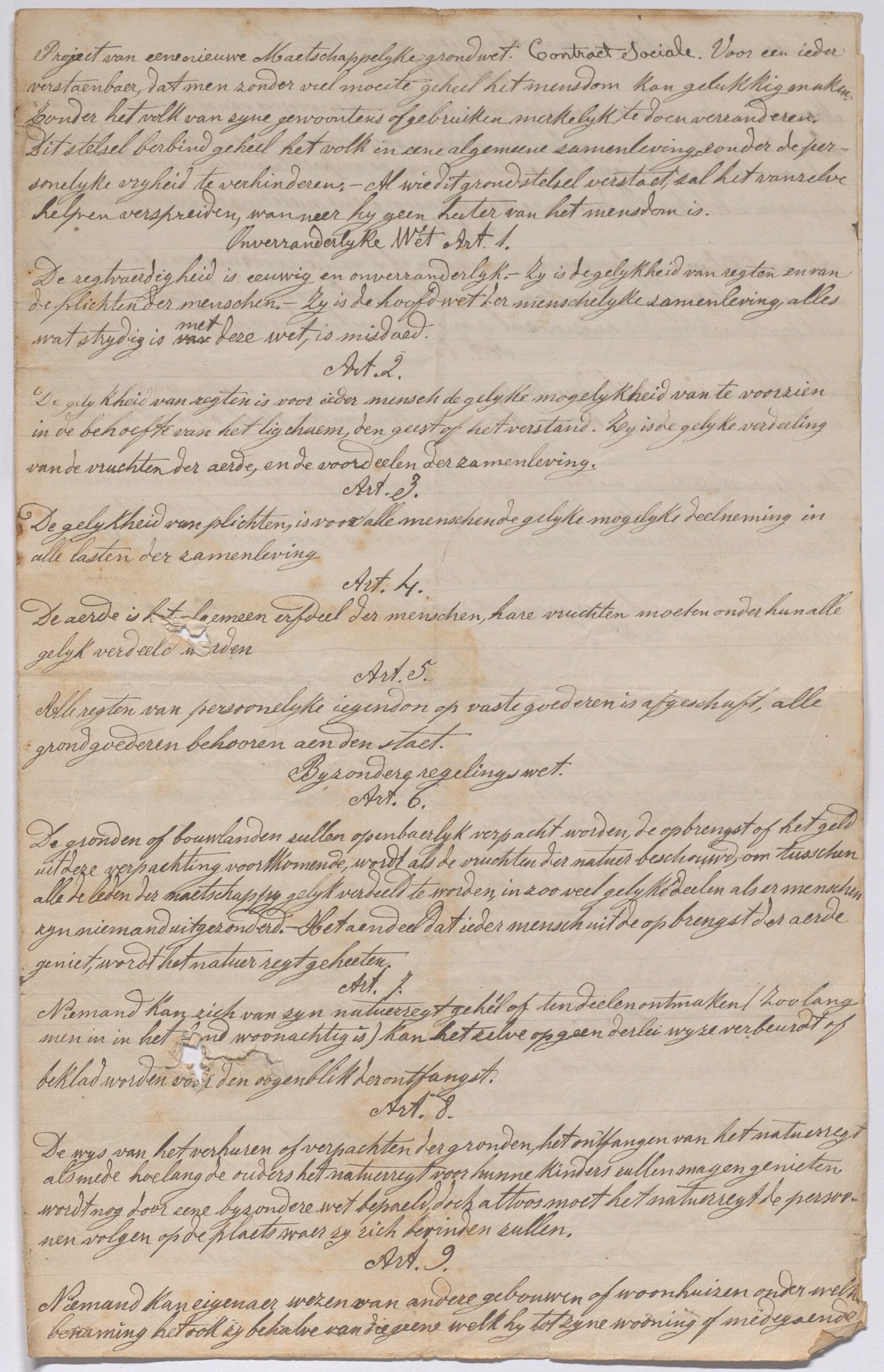

A new constitution and a basic income

On 28 March 1848, the police raided the house of Jozef Kats, one of Jacob’s brothers and confiscated two documents, including a manuscript of the Project for a New Social Constitution. That Constitution has never appeared in print, but clearly came from the entourage and/or the pen of Jacob Kats. In Articles 6 to 8 the idea of a “natural right”, in other words, a basic income, appears.

The manuscript of Project for a New Social Constitution comes from the entourage and/or the pen of Jacob Kats

The manuscript of Project for a New Social Constitution comes from the entourage and/or the pen of Jacob KatsAfter 1848, Kats shifted the focus of his activism back to the theatre and saw some of his pieces appear in the temples of “high” culture. In 1850 the second Language and Literature Congress was held in Amsterdam. Kats gave a speech about language and politics and linked both very naturally to his early socialist worldview. His rhetoric also reveals his literary credo: write in a “short, clear, comprehensible, attractive and instructive” manner. Still good advice for today! He also advocated a global language that would require consultation and cooperation amongst all nations.

Belgian stamp in honor of Jacob Kats and abbot Nicolas Pietkin

Belgian stamp in honor of Jacob Kats and abbot Nicolas PietkinThe following year, the Language and Literature Congress took place in Brussels and Kats was back. If we want to upgrade our ailing mother tongue, he said, we must keep an eye on the public interest. He was referring to the Dutch society Tot Nut van ‘t Algemeen (Society for Public Welfare). Language policy and popular education go hand in hand, he argued, and, finally, all language associations, in the North and South, should set up people’s libraries in towns and villages.

Kats’ Folk Poems were published in 1851 but the volume not only contains poems in the classical sense of the word, but also political treatises arranged in rhyme so that the reader or listener can more easily understand and remember them.

The People’s Theatre and the Flemish Theatrical Association

In 1850 Kats founded a new theatrical troupe: the Tooneel der Volksbeschaving (People’s Theatre). The performances had great success but were also very costly. Five years in, Kats applied for a subsidy from the city council but they only offered him a pittance: 1,200 francs (30 euros). Kats also knocked on the door of the Belgian government, but in vain.

In 1858 Kats brought The People’s Theatre and five other groups under the umbrella of the Vlaemsch Tooneelverbond (the Flemish Theatrical Association). They put on two or three performances a week. Kats appealed once again to the city council. Some council members agreed that De Volksbeschaving was a socially valuable project, and that Flemish theater was the only form of relaxation for the Flemish population of Brussels, who were the majority, but Mayor De Brouckère refused to provide any financial support. As a gesture of good will, however, the city agreed that the 1,200 franc subsidy that The People’s Theatre received would go instead to the Theatrical Association.

After sixty-seven performances, the Theatrical Association began to run out of steam – and money. The group went bankrupt in 1859, which wounded Kats deeply. After a busy and turbulent life, he withdrew from the public eye, despondent and broken by the government. Kats’ world became quiet and still.

Work and capital

In September 1872, at the age of 68, Kats published a sixteen-page pamphlet entitled Work and Capital.

Kats’ text reads like a theoretical elaboration of the utopian ideals that were addressed in his theatrical works, a recipe for realising an ideal society. And all that in only twelve pocket-sized pages!

Work and capital are the two “main sources of human existence,” writes Kats

Work and capital are the two “main sources of human existence,” writes Kats. Without either of these, society will “fall to pieces.” They are inseparable, “for capital can produce nothing without being worked, and without capital little or no work can be done.” Can we reconcile work and capital? Can a “harmonic alliance” be found between masters and workmen? Yes, argued Kats, but only in a system in which the profits derived from capital and labour are shared equally between the two parties. Within such a system, capitalists and workmen will work together in harmony and trust. The workmen will gain in-depth knowledge of their work and their business and, because they share in the profits, they will work with greater zeal and commitment. Order, consultation and frugality will become the norm and will, moreover, exert a positive influence on their behaviour as people and as citizens.

Kats died on 16 January 1886. Nine years earlier, the first socialist parties finally came into the light, in Flanders and Brabant – though Kats was no longer involved. In his In Memoriam, César de Paepe declared: “Had this man died forty years ago, his disappearance would have been an event throughout the country (…); Democratic delegates from all over the nation would have attended his funeral; and the whole working class of the capital would have been moved.”

Almost one hundred years later, in 1978, the historian Karel Van Isacker wrote: “In the beginning was Jacob Kats. (…) In August 1836 (he held) his first meeting “for the working class”. (…) Who could have guessed that this was the start of a movement that, after a maturing process of several decades, would bring the working class out of submission?”

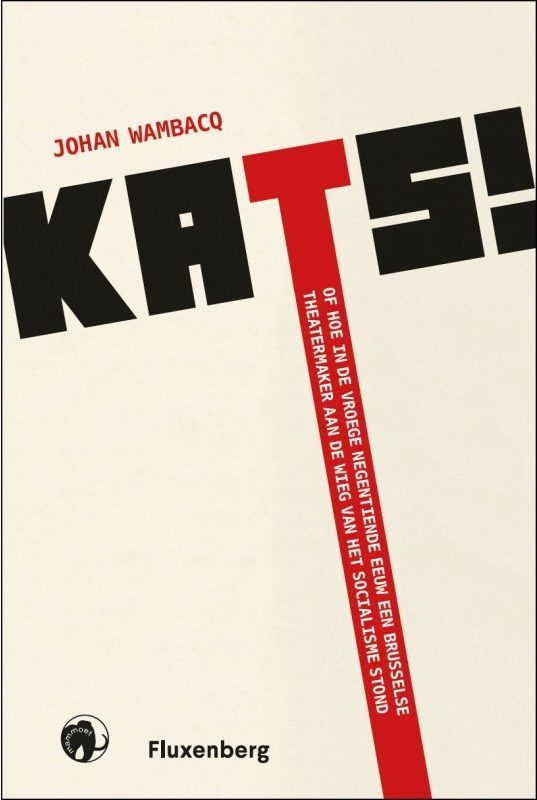

Johan Wambacq, KATS! Of hoe in de vroege negentiende eeuw een Brusselse theatermaker aan de wieg van het socialisme stond, Mammoet (Epo) / Fluxenberg, Antwerp / Brussels, 2021, 295 pages