Jeroen Olyslaegers and Siel Verhanneman Bridge the Corona Distance in Letters

Would you write each other letters during the coronavirus lockdown? Twenty-four Flemish writers and poets responded to colleague Joost Devriesere’s request with great enthusiasm. Their correspondence has been collected in the book De afstand (The Distance, Houtekiet), of which proceeds benefit the human rights organisation Doctors of the World. We translated the dialogue between Jeroen Olyslaegers and Siel Verhanneman. ‘Everyone is connected, we are all part of the world now, because we share fear.’

___________________________

Kortrijk, Monday 30 March 2020

pandemic

while outside a pandemic seeps across the country like a drop of ink on kitchen paper I watch from behind my newly washed windows

– here and there a streak there are things you’ll never quite get right in your life like cleaning windows and seasoning dishes – how we’re all locked down

others stick rainbows on the inside of the glass and leave white towels flapping on the third floor we haven’t got children to make rainbows and we haven’t got white towels either where do all these people get white towels from suddenly?

for days now we’ve been living hanging on each other’s lips waiting for the other to say something trivial that business with the towels is on his mind and the fact that we finally have support is on his mind too that we’re finally part of the world because now

everyone’s afraid.

Siel

___________________________

The French Ardennes, Monday 30 March 2020

Dear Siel,

Thanks for your mail – it looks like a poem. The last few lines have stayed with me. Everyone is connected, we are all part of the world now, because we share fear. I have often written that we are all connected and that this is the most tragic realisation of all, because we don’t see the implications of that connectedness. But now we do. Years ago, my beloved Nikkie and I, along with our friend Patsy and quite quickly a whole lot of other people, organised soup actions in Antwerp, with ‘we are one’ as our motto or slogan. We distributed free soup to draw attention to all the poor people in our city. I described poverty as a ‘problem of awareness’ for those that are well-off. The average person tries to see as little poverty as possible. We shut it out, often out of fear, because we don’t want to go down that path, a path which – as we suspect – is often endless. I think we dished out soup and other food on twenty-five consecutive Saturdays. During that period all sorts of things went through my mind. Not only did I start looking at the city of Antwerp completely differently, but I also felt a connectedness, a solidarity between the people that helped us. We often went home euphoric. There was something deceptive about that. The following day I would cycle through the municipalities around Antwerp to cure me a bit of the idea that we were changing the world. It was that intense. Because I saw the affluence during those bike rides, the two cars on the drive, the big houses, even the people seemed completely carefree. And that kept me in balance. Connectedness is not something vague. It’s a reality, we know that now. Nor is it something euphoric. It takes very different forms. Fear is part of that connectedness: the fear of infecting someone, the fear of being infected by someone else, fear of the indifference of the people who don’t give a damn about that connectedness.

you know what happens with balance and the peace of mind it gives you – it never lasts long, because everything is in motion

That’s why Friday 13 March was the most difficult day I’ve ever experienced in Antwerp, in the nearly thirty years I’ve lived there. That was when it was announced that all restaurants, cafés and bars would be shut down at midnight. What happened then was hallucinatory. Many people – many young people – went out partying. The bars were full. One of the bartenders went live on Facebook, showing people enjoying themselves madly while the beer flowed. All the warnings were cheerfully ignored, because yes, ‘it was the last time, after all, and we’ve a right to it’. That sort of bunkum kept going round. It was so in-your-face that it wasn’t even worth condemning it. ‘Please, stop and think,’ I wrote on Facebook. I felt like an idiot. What sense does it make to try and explain something to people who think their rights are being violated if the bars are closed to possibly save people’s lives? My wife and I went to bed feeling sad. Scarcely a day or two later we were out of there. We left the city I love so much for the house in the French Ardennes that we bought last year. In recent months, I have often wondered where I could actually live permanently. In the city or here? And I’ve felt hugely grateful that I’ve got both the city and the woods available to me, an old childhood dream that became reality last year. For the first time I felt in balance in that respect. But you know what happens with balance and the peace of mind it gives you – it never lasts long, because everything is in motion.

Jeroen Olyslaegers

Jeroen Olyslaegers© Koen Broos

Once we were here in France – the next day in fact – things suddenly became very strict. No one can go out on the street without a paper in their pocket, dated and signed, explaining what they’re doing there: going to work, fetching food, medicines, or going for a little walk within a radius of no more than a kilometre. We swallowed, and suddenly felt very afraid. But it didn’t last long. There’s something reassuring about strictness. We have one rather modest supermarket here. As you enter you are obliged to wash your hands and disinfect the handles of the supermarket trolley. There is security and a queue. But once we’re home we’re safely ensconced again. There’s more space here and we can store more food. We brought our cat Karma with us. I can work in the garden and write. Every day I’m thankful that my wife persuaded me to leave. After all, I wanted to stay in the city. I wanted to carry on as ‘normal’. I, please note, who labelled that sort of behaviour normalitis. Carrying on as normal – that’s how we exorcise fear, isn’t it? It used to be, anyway, in another era, barely a couple of weeks ago. Since our soup actions, since I started thinking about connectedness and what it means in our society, I’ve had a feeling that something would happen in everyone’s life that would make this connectedness obvious. I often used to think then that that was what I hoped. But now it turns out to be completely different. And I’m watching it from a distance, like everyone, because distance… is what it’s all about. Distance, fear, connectedness, we, everyone, no one excluded.

Warm regards and keep safe,

Jeroen

___________________________

Kortrijk, Thursday 2 April 2020

melancholia metamorphosis

have we all become glass who dares sit down without hesitating, there, on the white bench at the entrance to the park without the fear of breaking

we’re transparent now when we’re the first to decide to cross over so as not to pass someone else whoever made this footpath so small

Siel Verhanneman

Siel Verhanneman© Tine Schoemaker

looking through each other we see it lurking there, the unease, like a second beating heart between the other organs the only travelling we can still do is deep into what we try to remember what being carefree once looked like we fashion a fake version of it swallow it

our glass I complains that it lives caged and behind screens as if we hadn’t always that we can hardly touch no one wants cracks in another person’s matter I put a mark next to the words skin hunger every time I read them. we’re going up the wall we miss nature we’re rediscovering nature we love the little things and each other just that little bit more

while people are dying we become lyrical clap our hands every evening at eight shout

we are one

we see that, in the beating unease

we are one

beats the unease

we are one

Siel

___________________________

The French Ardennes, Thursday 2 April 2020

Dear Siel,

In the mail accompanying the poem you sent me, you tell me that you hesitate to listen to the news, because you regret it afterwards. I completely understand that. It’s also part of our ‘we’, isn’t it? That ‘we’ pops up in your poems, in the last one and in the first one too. But in your first poem that ‘we’ seems to be at home, you and your beloved. And in the second poem I assume that it is all of us. And we all exorcise fear with the information that the radio and television news broadcasts bring us.

For years I’ve really hated the news. It began in the autumn of 2008, when the bomb exploded and the global financial crisis began. I was listening to the twelve o’clock radio news one lunchtime. One item after the other, doom and gloom assailed me. I was seriously considering whether I should go straight to the bank and get my savings, and keep them under the mattress in future or, better still, among the dirty underwear. I was flipping out actually. And then came the stock market reports, as cool as you please – as if nothing were wrong. Then I thought, that’s enough. And I’ve never listened to the news again. I haven’t watched the television news since the early nineties, for the simple reason that I’ve never had a cable connection since I left my parents’ home. Sometimes we’re sitting in the car and the news comes on the radio. We turn it up a bit louder out of habit, and then I start swearing. It’s not news, in my opinion. It’s a series of incantations, exorcisms, and we generally take them much too seriously. It drives some people up the wall when you say that. They think it’s almost a duty to keep informed. But I believe in news that you look for yourself or news that you find. We have to distance ourselves from each other, perhaps we should distance ourselves from what people consider to be news, as well. Because I see a lot of people, on Facebook for example, just going crazy because of all that news. Perhaps it doesn’t work anymore as ritual exorcism? In any case, it’s not enough. And if it doesn’t work as exorcism it becomes poison.

We have to distance ourselves from each other, perhaps we should distance ourselves from what people consider to be news, as well

We exorcise ourselves with the past, too, by ascribing carefreeness to it, as I read in your poem. I get that too. And at the same time, it’s still remarkable these days, we create our own rituals by honouring healthcare professionals with daily applause. It’s quite something, all that exorcism. I certainly don’t think I’m above it. I keep my life together by making little agreements with myself, with meditations and even prayer meetings, with stuff on the yoga mat and wearing a white shirt every Sunday. I’m probably exorcising and ritualising a few things with that as well. But when it happens collectively, it seems somehow to invite satire. The people who work for the food suppliers and the refuse collectors ask, ‘what about us then, don’t we get any applause?’ And there are healthcare workers who are angered by all that clapping too, because ‘they’ve been making cuts in the healthcare sector for years, and now we’re suddenly all heroes, and what will happen at the next elections?’ Do you see? That’s what you get with these exorcisms. They always fall short. Just when you’re hoping they’ll support us all you find they’re faltering. And there’s no memory with them either. Once you start thinking about it all, you get this image of a masked parade that makes you want to laugh, makes us want to laugh at ourselves, myself included. As a writer that makes me sit up and think and take note and run the whole parade through my mind again, yes indeed, while people are dying. That’s what writing is for me, or rather, that’s writing too, continuing to be a seismograph in times of unease.

And yet at the same time I can’t bring myself to do it anymore. Maybe it’s temporary. I don’t know. I read aloud on Facebook, that’s all, at 12.15 and at 20.15. Sometimes I add a comment to this human comedy, but as often as not I remove it again. I’m paring myself down. I’m a storyteller, and the commentator has just become encrusted on me. It’s ballast and ballast makes it more difficult to delve down into yourself, on your inner journey, because that has become the real journey for me. I don’t need a diary to tell me that. Indeed, for me, stay at home is more than the hashtag you see everywhere now, it is an incentive to go deeper into my innermost self. And, while so many people are exorcising themselves with all sorts of stuff, I exorcise myself and try to discover things that live in me, old complaints, the urge for inner truth, and so on and so forth. The first thing I have to learn, so I’ve understood, is to worry less about what people think of me. It’s strange that that’s surfaced. It’s embarrassing too, awkward to just tell you that. But apparently that ballast has to go. The second is to stop being judgemental.

I think I have to take all the time I need to delve further into myself, regardless of the time we have to spend distancing ourselves from each other

One of those young people who partied in Aalst that Friday the thirteenth regrets it, I read somewhere. He and his mates were filmed by the television news, out on the town, living it up that last evening. The images haunt him. He wants to be made unrecognisable in the footage because, yes, he’s young and he didn’t know how bad it was then. A few weeks ago, I could have kicked him in the backside, but now I understand him. We’re in it together, everyone has his reality. We exorcise or don’t exorcise. Follow the news and get palpitations from it or don’t.

Do you know what, Siel? Right now, round 17.10 on 2 April 2020, it’s of no importance at all. None. I think I have to take all the time I need to delve further into myself, regardless of the time we have to spend distancing ourselves from each other. I think I will only discover that ‘we’ again, without being judgemental, if I first take a good look in the mirror and, having hurtled through the wormhole of my own awareness, hopefully discover what or who I am without the exorcisms of this particular period, of each and every one of us. That’s how it has to be, it seems.

Warm regards and keep safe, without poison.

Jeroen

___________________________

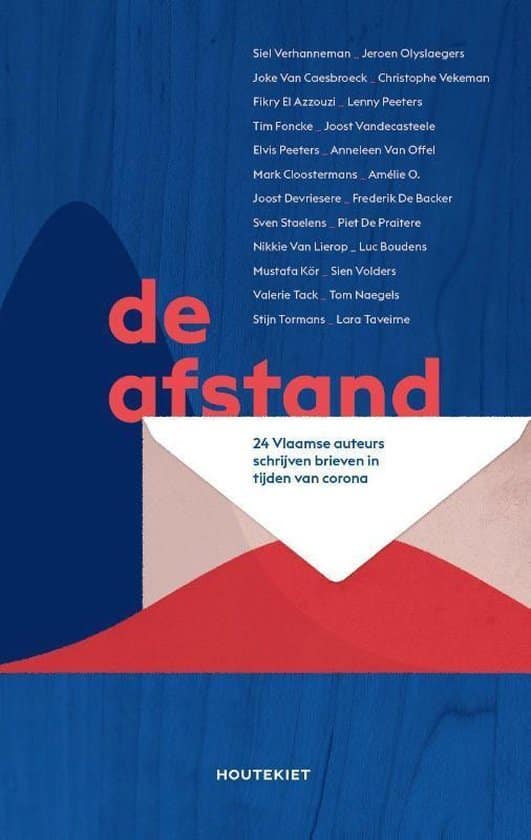

De afstand. 24 Vlaamse auteurs schrijven brieven in tijden van corona (The distance. 24 Flemish authors write letters in times of corona) was published by Houtekiet and contains correspondence between these writers’ duos: Jeroen Olyslaegers & Siel Verhanneman – Christophe Vekeman & Joke Van Caesbroeck – Fikry El Azzouzi & Lenny Peeters – Joost Vandecasteele & Tim Foncke – Lara Taveirne & Stijn Tormans – Tom Naegels & Valerie Tack – Nikkie Van Lierop & Luc Boudens – Mark Cloostermans & Amélie O. – Elvis Peeters & Anneleen Van Offel – Frederik De Backer & Joost Devriesere – Sven Staelens & Piet De Praitere – Sien Volders & Mustafa Kör.