Leonardo da Vinci: The One and Only ‘Uomo Universale’

500 years ago, on 2 May 1519, Leonardo da Vinci died in Amboise. On the occasion of the anniversary of his death, editor-in-chief Luc Devoldere makes a few comments on the notion of the uomo universale.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, Tongerlo Abbey, 1498

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, Tongerlo Abbey, 1498France and Italy are still battling it out over who can claim Leonardo da Vinci as their own. American art historian Jean-Pierre Isbouts contends that the grand master actually helped paint a copy of The Last Supper at Tongerlo Abbey. This almost full-scale Limburg version is indisputably one of the very best copies of the Milanese masterpiece, which started to fall in disrepair soon after it was finished in 1498, seeing Leonardo painted on dry, rather than wet, plaster with tempera in the fresco secco technique. Meanwhile, the original in Milan has been restored so many times, one might start to wonder whether it is in fact still truly Leonardo’s painting. Considering this, you do not have to fly to Milan; instead, just pay a visit to Tongerlo, where a version of the masterpiece has been on display ever since 1545.

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da VinciIf you have ever acted pretentious about any of your achievements – be they intellectual or practical –, you should read the application letter thirty-something Leonardo da Vinci sent to Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan. Whatever we may do, pales into insignificance compared to what this painter, sculptor, and architect managed to accomplish in his lifetime. The engineer who designed bridges, aqueducts, canons and catapults, knew that mathematics was the basis of everything, but was also able to custom-design parties with special effects and gadgets. He was also a perpetual dreamer, and would come up with impossible models, objects that would actually be made centuries later, including bikes and tanks. True, he left many designs unfinished (that should not come as a surprise when you are capable of so much), made regular mistakes, and wanted – and did – too much.

Leonardo referred to himself as ‘omo sanza lettere’, illiterate, as he had not been educated in the scholarly language of Latin. Nevertheless, he was still able to make sharp observations in that language, and coined some wonderful Latin aphorisms. He spent the last few years of his life in Amboise, where he was given a chateau by King Francis I, topped with a generous fee to spend a full year thinking and doing what he wanted, free of any specific responsibilities. All the King wanted in return was to have pleasant conversations with the artist.

François-Guillaume Ménageot, The death of Leonardo da Vinci in the arms of Francis I, 1781

François-Guillaume Ménageot, The death of Leonardo da Vinci in the arms of Francis I, 1781© Musée de l’Hôtel de Ville, Amboise

Most likely, Da Vinci, who had a penchant for young men, did not die in the King’s arms, as one painting in the Amboise room in which he died would have us believe. When Leonardo passed away, Francis I stated that such a man should be mourned by all of humanity for it is not in the power of Nature to create another.

Model of da Vinci’s armored vehicle based on his sketches

Model of da Vinci’s armored vehicle based on his sketches© Wikimedia Commons

Leonardo went down in history as the uomo universale incarnate: artisan, scientist, and artist, all rolled into one. In the century that followed, science, technology and literacy would drift apart permanently. Today, we are still dealing with a gap between literacy and numeracy, i.e. natural sciences, mathematics, and technology on the one hand, and liberal arts and humanities, the humanistic disciplines, the world of the literary intellectuals on the other. British scientist and novelist C.P. Snow described it as “two cultures” in his acclaimed 1959 lecture in Cambridge.

Things are not looking up. Ever since the explosive growth of – predominantly – the natural sciences in this Modern Age, we seem to know more and more about less and less.

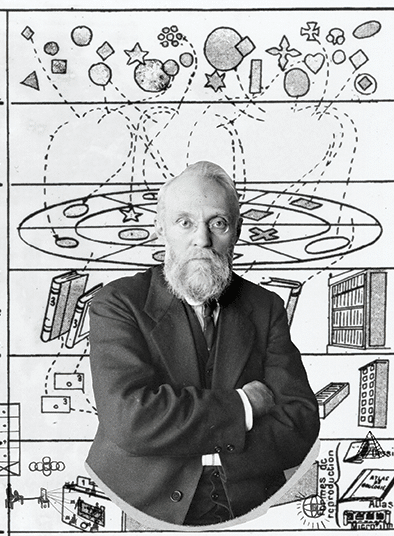

Paul Otlet

Paul OtletIn the fourth century B.C., people dreamed of collecting every snippet of available knowledge on papyrus scrolls in the great library of Alexandria. At the start of the twentieth century, Paul Otlet, a Belgian, aimed to capture the entire world’s knowledge by means of… index cards. His so-called Mundaneum

was never finished. The 1990s marked the exponential growth of the modern Internet, which would bring us one step closer to Otlet’s dream. What has changed, however, is that we have gotten used to the idea of not having to know anything, as everything can be found within seconds. Our knowledge has become virtual. Our knowledge is interconnectedness, with the possibility of knowledge. We are connected, anytime, anywhere, empty and full of expectation.

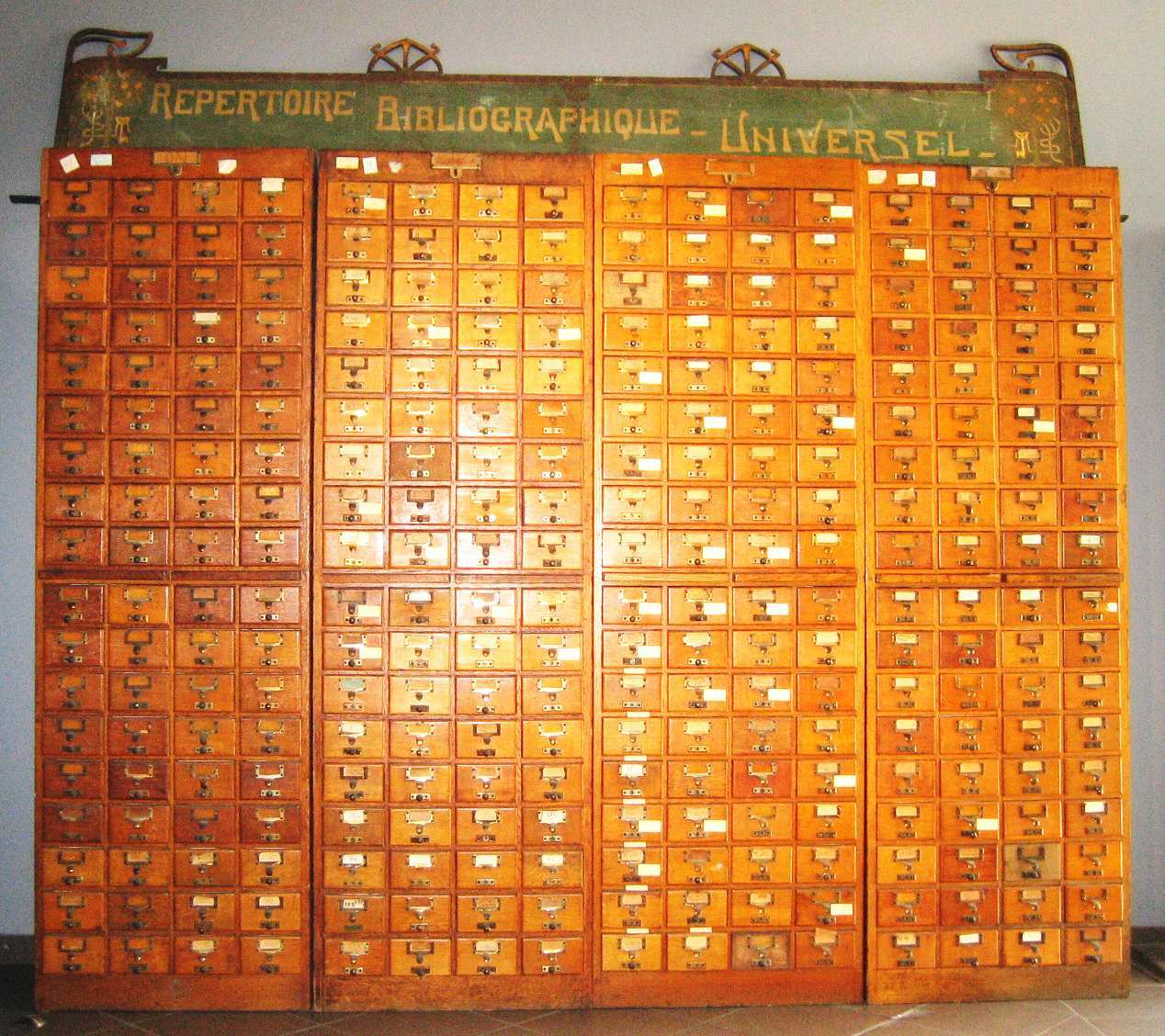

Drawers of the Mundaneum's Universal Bibliographical System

Drawers of the Mundaneum's Universal Bibliographical SystemMaybe this alleged uomo universale never truly existed. Let us invent him, right here right now, as a necessary, useful figment of our 21st

century imaginations. A contrary, unzeitgemässe

version.

He will choose conversations over communication, the meandering path over the straight one, the detour over the destination. He knows all the French King ever really wanted from Leonardo was a conversation. He will not take dilettantism as a reproach, but will wear it as a badge of honour. His freischwebende Intellligenz will pursue leggerezza, a lightness – not the airiness of a feather, but that of the bird – and above all: sprezzatura, the art of making what is difficult seem effortless, the art of… hiding the artistry of art, a noble nonchalance.