The Influence of Netherlandish Printmaking Spanned From Italy to Russia

It is noticeable that there has been an international passion for prints from the Low Countries recently. Museums from all over the world have been organising exhibitions and congresses on engravings and etchings, especially those from the dawn of the Golden Age. That is not really surprising because, from the 16th century onwards, the centre of European printmaking was in the Low Countries. First in Flanders and then in the Netherlands.

In the late 16th and the 17th century there was a sudden explosive production of prints in the Low Countries. This massive production was mainly due to the establishment of print shops. These functioned not only as shops but also as international meeting places for artists, art dealers and buyers. The most important print studio in 16th-century Europe was, without doubt, In the Four Winds, a print shop that the painter and engraver Hieronymus Cock (1517-1570) and his wife Volcxken Diericx (ca. 1525-1600) opened in Antwerp in 1548.

In the Four Winds, Hieronymus Cock and Volcxken Diericx’s print shop in Antwerp (right) Engraving from 1560 by Joannes and Lucas van Doetecum after Hans Vredeman de Vries, Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels

In the Four Winds, Hieronymus Cock and Volcxken Diericx’s print shop in Antwerp (right) Engraving from 1560 by Joannes and Lucas van Doetecum after Hans Vredeman de Vries, Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels© Wikimedia Commons

In the Four Winds was a place of cultural exchange, where a rich cross-fertilization of cultures took place, where Italian and Flemish artists, merchants, humanists and art dealers from the whole of Europe met each other, where prints were traded and where new trends in art emerged.

We have a print of the shop by Joannes and Lucas van Doetecum, after Hans Vredeman de Vries, that offers us an idealised imaginary view of the street with In the Four Winds on the corner (figure 13 from Scenographiae sive perspectivae from 1560). Cock stands in the doorway of his shop and his wife poses behind her counter. Below the engraving we read, Laet de Cock coken om tvolckx wille, or ‘Let the Cook [Cock] cook for the benefit of the people [tvolckx]’, a pun on the names of the owners, Cock and his wife Volcxken. A pithy detail is that the wife of Hieronymus Cock, Volcxken Diericx, ran the most prestigious print shop in the North for another thirty years after the death of her husband, in 1570, and proved to be a clever businesswoman.

Thousands of prints found their way from here to the rest of Europe and established the fame of Flemish printmaking in the art world of the time. From Italy to St. Petersburg, the influence of printmaking from the Low Countries was huge.

Thousands of prints found their way from In the Four Winds to the rest of Europe and established the fame of Flemish printmaking in the art world of the time

It was Hieronymus Cock who helped establish the fame of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and others, all over Europe. Bruegel drew more than sixty designs for Cock, which were then cut in copper by the best engravers of his time. The complete collection of Bruegel’s very diverse prints is still housed in the Print Room of the Royal Library of Belgium and was exhibited in its entirety, in Brussels, on the occasion of Bruegel Year, in 2019. Those who visited the exhibition will have been overwhelmed by Bruegel’s genius and talent and will probably understand very well that his fame in his own time was primarily derived from his printmaking.

Some may perhaps be most impressed by his series of twelve Large Landscapes, which have had a pioneering and lasting influence on European landscape art. I personally was particularly charmed by the inimitable storyteller and mocking moralist directing his sarcasm at mankind’s weaknesses in his many narrative etchings. I can stand for several minutes enjoying a satirical print like The alchemist. The portrait of the alchemist and his fanatical experimentation, a foolish materialist, squandering the last of his possessions in a fruitless search for the philosopher’s stone, as he drives his family into the poorhouse, impoverished and hungry, is both witty and wry. The open book, with the unmistakeable wordplay Alghe – mist ‘all missed’, is a compelling summary of the print’s message and is, at the same time, a typical feature of printmaking, which frequently linked image and text to make a meaningful whole. The alchemist, standing there amid foul smells has, after all, missed everything (alles gemist) life has to offer and, above all, abandoned his family to their sad fate.

The alchemist (1588), engraving by Philips Galle (1537-1612) after Pieter Bruegel the Elder

The alchemist (1588), engraving by Philips Galle (1537-1612) after Pieter Bruegel the Elder© Wikipedia

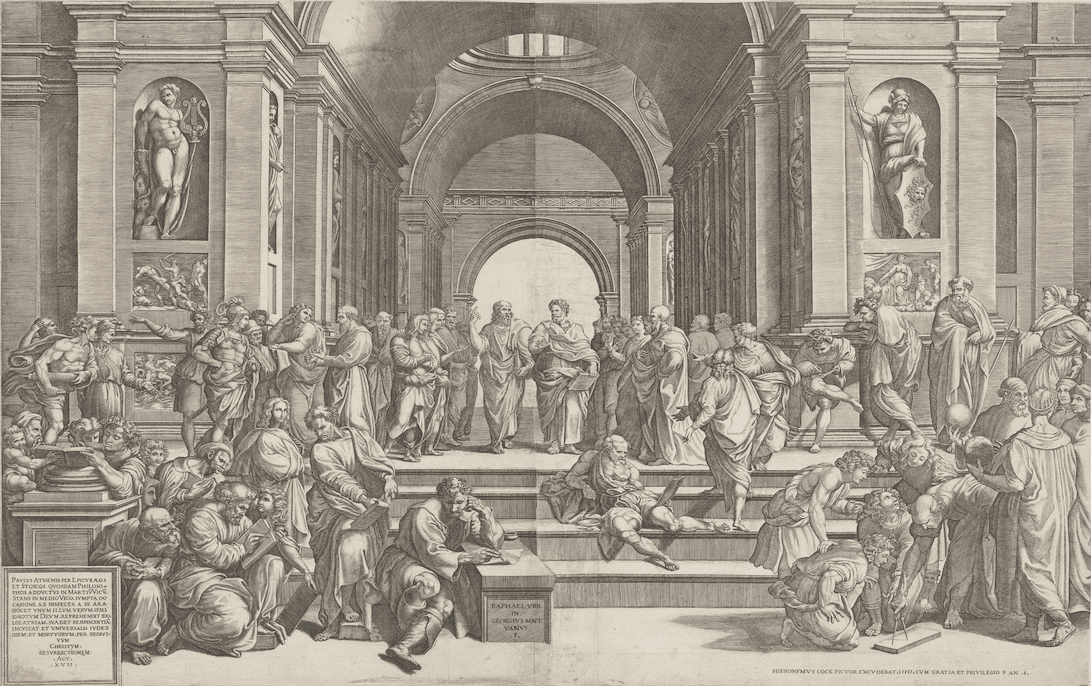

Hieronymus Cock has remained best known as the publisher of Bruegel’s prints, but he was first and foremost a shrewd merchant with a nose for business, refined taste and an international outlook. In 1550 he took on the renowned Italian engraver Giorgio Ghisi, who engraved six large plates for him, including the magnificent copperplate engraving of The school of Athens, Raphael’s famous fresco in the Vatican. Thanks to prints like these, art in the Low Countries came into contact with the Italian Renaissance, so print shops acted as influential stimuli in the cultural mobility of Netherlandish art.

Etching is a much faster technique than engraving, so it was used more frequently for prints that dealt with current affairs or for cheaper prints

Initially, prints were mainly engravings. However, engravings were more laborious and time-consuming than etchings, requiring the artist to engrave directly onto his copperplates with a burin. An engraving like The school of Athens could keep an experienced engraver busy for a year. Etching is a much faster technique, so it was used more frequently for prints that dealt with current affairs or for cheaper prints, such as illustrations for bibles meant for the general public. Etchers could just draw straight onto the coating covering the copperplate with their etching needle. The drawing was then burned into the copper with acid, after which the coating was removed. It was much faster than engraving and, in addition, more copies could be made from an etching plate.

The School of Athens, engraving by Giorgio Ghisi (1520-1582) after Raphael

The School of Athens, engraving by Giorgio Ghisi (1520-1582) after Raphael© Rijksmuseum

Copperplates were a precious commodity and were therefore used with great care. If there was renewed demand, they were reprinted, with modifications if necessary. We know, for example, that Rembrandt very often made changes to etching plates that had previously been printed, working with a so-called dry needle or, in other words, straight onto the copperplate.

Printmaking in the Netherlands

In the early modern period, there was no marked division between printmaking in Flanders and in the Netherlands. Engravers travelled easily from South to North and vice versa. There was a brisk trade in copperplates, too. For example, the Collaerts, a Brussels-based family of engravers, had close contacts with print publishers in Amsterdam and Haarlem.

Detail of a map of the Netherlands and surroundings from 1630, showing the "Fisher logo" of the Visscher family, mapmakers in Amsterdam

Detail of a map of the Netherlands and surroundings from 1630, showing the "Fisher logo" of the Visscher family, mapmakers in Amsterdam© Wikipedia

Conversely, the Haarlem print publisher Claes Jansz. Visscher, who had an extremely flourishing business on the Dam in Amsterdam, owed his early successes to the publication, in 1612, of a series of landscapes which he had copied from two sets of landscapes that Hieronymus Cock had published in Antwerp, in 1559 and 1561. Indeed, throughout his life, Visscher bought the copperplates he copied – mainly landscapes – elsewhere. He was the top print producer in the Netherlands and sold anything for which he could find an eager public, be it Bible prints, political prints, portraits, maps, landscapes, or even lottery prints.

Hendrick Goltzius, a chameleonically gifted printmaker

The most famous and most gifted early modern engraver in the Netherlands, Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617), also worked both in the South and the North. He started off engraving for the publishers Hieronymus Cock and Philips Galle in Antwerp, but later he went to work for Hans Jacops in Amsterdam and Harmen Adolfz. in Haarlem. Then, from 1582, he began to publish prints himself and managed a successful print business, likewise in Haarlem.

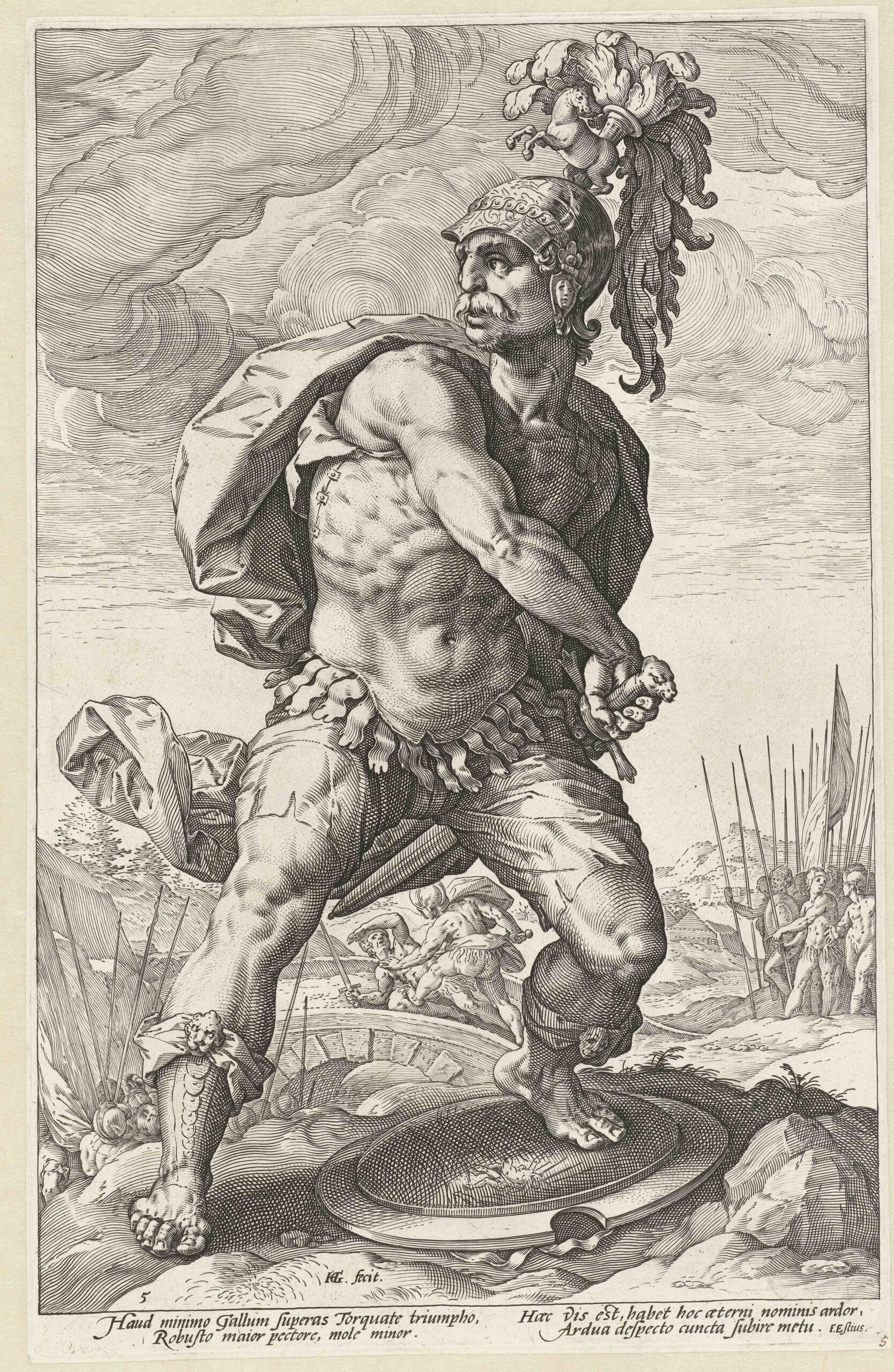

Goltzius was wonderfully inventive and a revolutionary stylist, and constantly introduced new sorts of prints. In his Schilder-Boeck (The Book of Painters), published in 1604, his friend and biographer, Karel van Mander, referred to him not undeservedly as the Proteus or Vertumnus of the art, ‘because he has miraculously mastered the art of imitating the various styles of the greatest masters’. Over and over again, he managed to amaze and surprise art lovers from all over Europe with fantastic prints and innovative techniques. His Four Disgracers and his Roman Heroes introduced a typical northern mannerism, with pronounced anatomical exaggeration and twisting, with superior and extremely detailed surface graphics, and graceful, swelling burin lines.

Over and over again, Goltzius managed to amaze and surprise art lovers from all over Europe with fantastic prints and innovative techniques

The Roman hero Titus Manlius Torquatus (1586), pictured here, from a series of ten prints, is a monumental soldier, who fearlessly draws his sword from its scabbard against the background of a battle scene, in which he vanquishes a Gallic soldier. It is a picture of extraordinarily vital strength and intensity, demonstrating incredible technical refinement in the graphic expression of anatomy, light and shadow.

After his death, Goltzius’s mastery was long underestimated, but in recent years his art has enjoyed renewed interest worldwide, including an exhibition that was enthusiastically received in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Toledo Museum of Art in Toledo.

(continue reading below the picture)

Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1616/1617), Titus Manlius Torquatus (1586) from the series The Roman Heroes, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1616/1617), Titus Manlius Torquatus (1586) from the series The Roman Heroes, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam© Rijksmuseum

Rembrandt, the great master of printmaking in the Golden Age

During the first decades of the Golden Age, Netherlandish artists like Esaias Van de Velde, Jan van de Velde II, Willem Buytewech and Adriaen van Ostade actively looked for new technical means of expression to be able to graphically reproduce the tonality and atmosphere of paintings more closely. They used dashes, new hatching techniques, broken lines and dots.

Printmaking did more even than painting to familiarise Europe with art from the Low Countries

The great master of 17th-century Netherlandish etchings, Rembrandt (1606-1669), must have studied all that experimentation with more than ordinary attention. In the more than three hundred etchings that he left us, he ingeniously combined all sorts of techniques and took the art of printmaking to unprecedented heights of perfection. Rembrandt continued to experiment throughout his life. He knew which scratches and strokes to use on the copperplate for the right effect, made his own etching ground and tested how acid ate into the copper to create shadow. Often, he did not even make a sketch first, but worked directly on the plate with his etching needle. The effects of light and shadow had never before been so nuanced when printed in black and white on paper.

The Three Trees (1643), etching by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Three Trees (1643), etching by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam© Wikipedia

In The Three Trees (1643) we see how a thunderstorm passes through a summer sky. The clear sky above the meticulously detailed trees is gradually covered by the roughly incised slanting slashes of a thunderstorm. This is his most famous and most frequently reproduced etching, because of the sublimely dramatic light effect, but also because of the surprising combination of techniques: etching, dry needle and burin. While the thunderstorm is scratched roughly into the plate with sharp, diagonal dry-needle strokes, the peaceful scene on the left, with the group sitting outside under the storm clouds, has, in contrast, been carefully drawn with fine curving lines and makes a sophisticated chiaroscuro effect with the three trees on the right.

Ecce Homo (1655), etching by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669)

Ecce Homo (1655), etching by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669)© Wikipedia

This etching is very different from two other famous monumental prints of his, the Hundred Guilder Print and the Ecce Homo. The Hundred Guilder Print is actually a depiction of several Bible stories in one print, all taken from chapter 19 of the Gospel according to St Matthew, but it takes its title from the fact that the then impoverished Rembrandt himself had to pay a hundred guilders to buy back a copy of his own etching. The Ecce Homo, from 1655, is an extremely large etching on expensive Japanese paper, in which Christ is shown to the people. Its rare first state was sold in 2018, by Christie’s in London, for three million euros.

Artistic influence

Printmaking did more even than painting to familiarise Europe with art from the Low Countries. As early as the 17th century, Netherlandish prints were being eagerly collected by art-lovers and monarchs from all over Europe. Painters were very well aware of that, and several painters made engravings or etchings themselves or had them made of their own work.

For example, in 1655, Rembrandt made an etching of his painting Abraham’s Sacrifice, from 1635. In the same way, landscape painters like Hercules Segers, Esaias van de Velde and Abraham Bloemaert made the Dutch landscape widely known. Cornelis van Haarlem (1562-1638) had Goltzius make copies of his classic mythological works, such as Two Followers of Cadmus Devoured by a Dragon (1588) and The fall of Ixion (1588), which gave him name recognition abroad.

As early as the 17th century, Netherlandish prints were being eagerly collected by art-lovers and monarchs from all over Europe

Rubens, too, understood the importance of etchings of his works. He surrounded himself with the best engravers of his time, both Flemish, like Theodoor and Cornelis Galle, and Dutch, like Willem van Swanenburgh, Pieter Soutman and Lucas Vorsterman, to avoid poor-quality pirate copies being distributed.

Because, indeed, the enormous popularity of prints meant that quite a few engravers surreptitiously distributed pirate copies. Great artists, such as Rubens, Van Dyck and Jordaens, preferred to choose their own engravers. Precisely because of the many prints, the artistic tradition of the Low Countries ensured enormous cultural mobility in European art. Netherlandish printmaking had a strong impact on religious art in the Balkans, for example. In Paris, too, there was a large influx of Flemish prints in the 17th century, and we can see the influence of Netherlandish engravings on Russian decorative art.

Friedrich Hollstein (1888-1957)

Friedrich Hollstein (1888-1957)Netherlandish printmaking was a source of inspiration even for Persian painters during the period 1650-1680. Recent art history research has made this increasingly clear. The same recent research interest has led to a prestigious international compilation of all the Dutch and Flemish etchings, engravings and woodcuts from the period 1450-1700. It is known as The New Hollstein, after Friedrich Hollstein who, till his death in 1957, worked on a large reference catalogue. Since 1999 it has been constantly supplemented with new volumes, full of updated scientific information, filled lacunae, and fresh insights. New collections are still being discovered and studied, and it is obvious that scientific research into Netherlandish printmaking will continue to rise.

This article was first published with the title Nederlandse prentkunst bekend van Italië tot Rusland, in Neerlandia, 2020, volume 124, no. 2, pp. 24-27. Neerlandia, a Dutch-Flemish journal for language, culture and society, is published by the Algemeen-Nederlands Verbond (ANV).