The State of Flemish Cinema: Professionalisation Pays Off

It took protests and demands by directors and producers to get a proper Flemish film fund up and running. And while the region was late to the party, the progress it has made in the sector in twenty years is nothing short of remarkable.

It was impossible to miss the headlines as the world’s most famous film festival kicked off this year. “Belgium makes history at Cannes” and several variations thereof dominated the news for a number of days, as a record three films were selected to compete for the Palm d’Or – and as a record three prizes came home with local directors.

It was the first time Flemish filmmakers won both the Jury Prize (The Eight Mountains) and the Grand Prix (Close) – second only to the Palm d’Or – in the same year. Then to top it off, the latest film by the Dardenne brothers – a Flemish co-production – won the festival’s special 75th anniversary prize.

“There is no miracle; we have not found a holy grail,” says Karla Puttemans with a smile. “It’s a combination of coincidence, talent and sectoral support. Right now the reputation of our sector is quite strong abroad.”

Blood, sweat and tears

Karla Puttemans, Head of Content at Flanders Audiovisual Fund

Karla Puttemans, Head of Content at Flanders Audiovisual FundIt was not always so. Puttemans is the Head of Content at Flanders Audiovisual Fund (VAF), which provides financing for film, TV series and digital games, as well as personal coaching for budding filmmakers. She is unique in the organisation in that she was there from the beginning, when VAF was founded in 2002 but also in the lobbying efforts to get it established 10 years earlier.

In the early 1990s, Flanders had no real film industry. While funding for projects had been technically available from the federal government since the 1960s, making one’s way through the process was challenging, and lonely. There were few production companies and no structural assistance. Films that got made were the result of blood, sweat and tears by tenacious filmmakers and producers.

In the early 1990s, Flanders had no real film industry

“You had a producer and the assistant, and sometimes only the producer, and that was the company,” says director Stijn Coninx, who was also part of the early ’90s movement to structure some kind of cinema foundation. He chuckles as he recalls what it was like. “In the 1980s, we produced about three films a year. I was the assistant director on almost every film ever made.”

Grassroots effort

Many producers and filmmakers were involved in the effort to professionalise the industry, including Flemish horror film pioneer Harry Kümel and Robbe De Hert, a key figure in the Antwerp scene – the hub of Flemish filmmaking at the time.

The public-private partnership Flanders Image was formed in 1990 to promote local cinema abroad. But this was just a start for the movement, which really took off a couple of years later with the Oscar nomination for Daens. The 1992 biopic of the famous 19th-century priest from Aalst, who was instrumental in local labour uprisings and condemned for it by the Catholic Church, was the first Flemish film to ever be nominated for the foreign-language Oscar.

It was Coninx’s third film, following two very different projects – broad comedies starring the Flemish comedian known as Urbanus. Those films – Hector and Koko Flanel – were incredibly popular with movie-goers. “Suddenly one million people in Flanders were going to a Flemish movie,” he says. “At the time, that was a lot.”

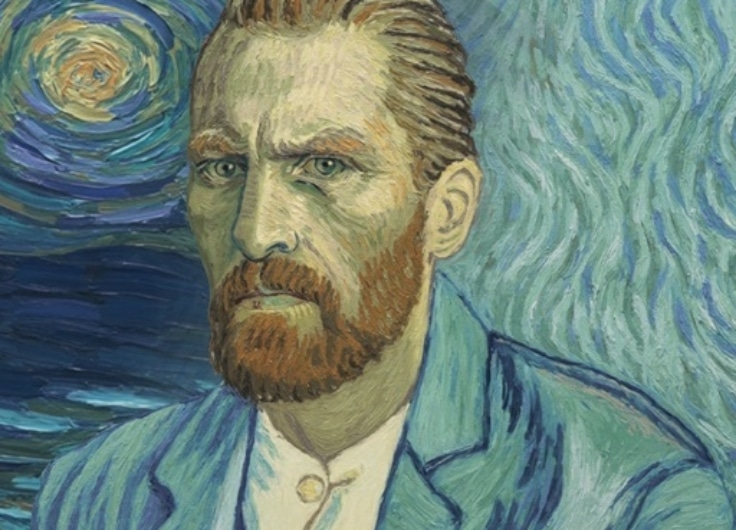

director Stijn Coninx

director Stijn Coninx© IMDb

The international success of Daens came just a few years later. “It was a wake-up call,” says Coninx, “to what was possible.”

Members of the industry began contacting various cabinets in the Flemish government. “We told them they had to do something,” recalls Coninx, “or we are going to leave and make films somewhere else.”

‘Linear approach to film financing’

The regional government quickly established the Fonds Film in Vlaanderen. It was a start, but it was seated within the administration and lacked a holistic approach. “It was a very linear way of coping with film financing,” explains Puttemans, who was then working in the audio-visual department of a copyright agency. “They were very much focused on receiving and choosing projects, funding them, and that was it. Our movement was about creating an independent film institute, like in the Nordic countries. We were always jealous of them because they not only subsidised movies but were also involved in all kinds of activities to create the right environment for films to flourish.”

Karla Puttemans (VAF): 'Our movement was about creating an independent film institute, like in the Nordic countries'

It would take nearly another decade before that dream came true, as the Fonds turned into VAF. In the years between, two key producers – Pierre Drouot and Erwin Provoost – travelled to Los Angeles to study the entire filmmaking process in one of the world’s biggest film industries. They brought famed script doctor Frank Daniel to Flanders to lead classes on screenwriting. Influential Belgian director Jaco Van Dormael, for instance, followed these classes. Coninx calls this period the start of the new Flemish cinema.

Coninx himself studied screenwriting in France. Importing instructors or leaving the country to learn skills flags up another problem. While there were film schools, the classes were taught by filmmakers who themselves had never been formally trained. It was only by perfecting every aspect of filmmaking that the industry could help reform schools so they could send out graduates with the skills they needed in writing, art direction, photography and the post-production process.

Turning points

Today, VAF provides subsidies to film and TV productions as well as game developers. It offers courses and workshops and matches coaches from the industry with new filmmakers. It collaborates with film schools, and it fosters relationships with foreign producers. Flanders Image still exists and is part of VAF.

In 2012, Screen Flanders was launched, which works to bring productions to Flanders and involve Flemish artists and studios in productions abroad. It is greatly helped by the tax shelter, a system of financial incentives launched right about the same time VAF was established.

The 2022 Cannes festival was not the first sign that Flanders’ film industry had reached a turning point. That, says Puttemans, was in 2009, when three productions went to Cannes – De helaasheid der dingen (The Misfortunates) by Felix van Groeningen, Lost Persons Area by Caroline Strubbe and Altiplano by Peter Brosens and Jessica Woodworth. “That was a year where we thought, wow, we really have a lot of talent,” says Puttemans. “I had the feeling that there was something very interesting happening.”

In 2012, Michaël Roskam’s first feature film, Rundskop (Bullhead), was nominated for the foreign-language Oscar. Just two years later the honour fell to Van Groeningen’s The Broken Circle Breakdown.

The change of perception of Belgian cinema over the last 20 years cannot be overstated, according to Christian De Schutter, head of Flanders Image. He credits the arrival “of a new generation of filmmakers like Felix van Groeningen, Fien Troch, Michaël Roskam, who were aiming for international recognition. And 2021 was a bumper year for documentary filmmakers, who won several awards internationally.”

Quirky and human

Looking at movies made by those directors and others from the region does lead to an overall impression of Flemish cinema. “Festival curators tell us that many of our films are quirky but also that our filmmakers approach topics with a lot of humanity, a lot of compassion.”

Van Groeningen’s first feature film, Steve + Sky, was one of the first films VAF subsidised. It has been behind the director ever since, as his career has blossomed, taking him from Flanders to Italy to Hollywood. Director Lukas Dhont, meanwhile, who won the 2022 Grand Prix with Close, has never known a career without VAF, without being surrounded by professionals in every task of making a movie.

Coninx has bridged the decades, continuing to make movies today. The biggest difference is the skill set he says. “It’s so professional now, which is an unbelievable change. You have so many young people with a lot of talent. Making a movie now is a totally different experience.”

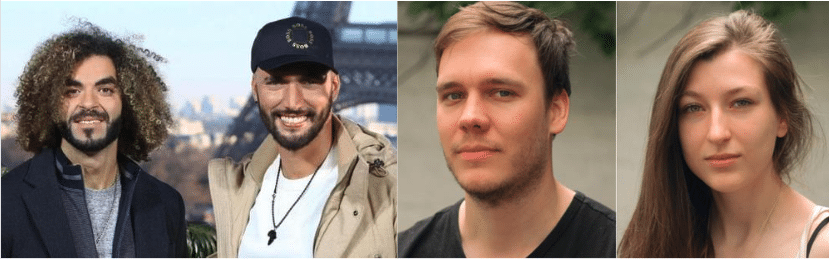

Flemish directors: Who’s hot right now

Lukas Dhont, Eva Küpper, Felix van Groeningen

Lukas Dhont, Eva Küpper, Felix van Groeningen© Wikipedia

Lukas Dhont – Gearing up to be Belgium’s new Cannes poster boy, Dhont made the ground-breaking film Girl, which pulled down four awards at the festival in 2018, including the Caméra d’Or. His 2022 film Close won the Grand Prix for its sensitive portrayal of the changing relationship between two boys on the cusp of adolescence.

Eva Küpper – Always engaging and surprising, Küpper’s many documentaries include Gardenia: Before the Last Curtain Falls, the inspiring story of aging drag queens on one last tour. Her latest film, Dark Rider, follows the Australian Ben Felton as he attempts to break the world speed record for a blind motorcycle rider.

Felix van Groeningen – The director has made seven features, including De helaasheid der dingen (The Misfortunates) and The Broken Circle Breakdown, considered among the finest of modern Belgian cinema. The Eight Mountains – written and directed with Charlotte Vandermeersch – won the Jury Prize at the 2022 Cannes Film Festival.

Adil El Arbi and Bilall Fallah, Marc James Roels and Emma De Swaef

Adil El Arbi and Bilall Fallah, Marc James Roels and Emma De Swaef© rr

Adil El Arbi and Bilall Fallah – The filmmaking duo made a splash with their second film Black, a Romeo and Juliet story played out among rival gangs in Brussels. Hollywood called on them to make the third Bad Boys instalment, which they followed up this year with Rebel, taking on the radicalisation of young Muslim men.

Emma De Swaef and Marc James Roels – Credited with reviving the interest in felt as a material in stop-motion animation, De Swaef and Roels have won multiple awards for their shorts Oh Willy…, This Magnificent Cake! and Otto. Their unique style can be seen on Netflix in the feature film The House, called one of “the scariest stop-motion animation movies to come out in years”.