How Huib Hoste Fought for a Modernist Rebuilding of the Westhoek

After the First World War, West Flanders’s Westhoek looked like a moonscape, littered with craters and munition. But rebuilding started almost immediately after the last shots. Flemish architect Huib Hoste played a unique role in this. Under the influence of his Dutch colleagues, he advocated a new architectural idiom to embody the changed postwar society. But his innovative ideas quickly clashed with residents and their yearning for the past. Nevertheless, Hoste did manage to leave behind some modernist pearls in the Westhoek.

‘Rebuilding had to happen fast, so the decision was taken to appoint an architect for groups of two or three municipalities. I was allocated Zonnebeke, amongst others, and the young ‘frontline priest’ asked me to build a new church to replace the one that had been completely destroyed. It was to be a Romanesque church, that was the order. ‘One with heavy walls and sparse openings, then?’ I asked. ‘No, a church with rounded arches’, came the answer. The Bishop approved my design and I won’t tell you how we managed to circumvent the commissions. I gave the priest a church with rounded arches, a reinforced concrete roof, visible from the inside, a tower next to the church, and so on. Actually, the priest was not very pleased; he had a banal retaining wall built instead of the one I had drawn and, with the exception of the main altar, he had the furnishings designed and produced by others in a very different spirit. Nonetheless, a lot of priests who had to build a new church went to visit Zonnebeke, praised it highly, wanted nothing but a church of that type built and… gave the job to others’. [1]

In the former frontline region of West Flanders, there are hardly any buildings from before the First World War. After the utterly devastating impact of the war, it was the reconstruction of the Westhoek that gave it its present appearance. The debate about what shape postwar reconstruction should take started as early as 1914. [2] The British garden city movement and hygiène urbaine were high on the agenda. In a garden city district, workers live together in reasonably comfortable houses in a green environment with communal facilities. Hygiène urbaine, on the other hand, was a French influence whereby redevelopment and healthy living conditions were the priority. [3]

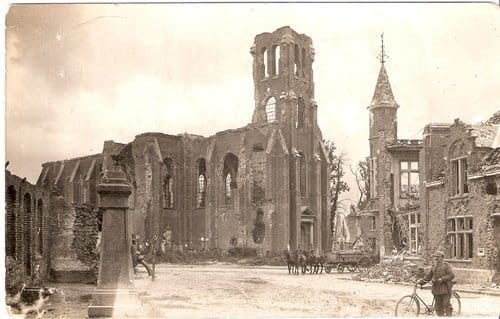

The destroyed Church of Our Lady and town hall of Zonnebeke, after the First Battle of Ypres in 1914

The destroyed Church of Our Lady and town hall of Zonnebeke, after the First Battle of Ypres in 1914© Westhoek Verbeeldt

Traditionalists versus modernists

The debate was mainly dominated by the so-called traditionalists and modernists. Traditionalists wanted to rebuild municipalities to once again look as they had historically. Anything that did not match the typical local, historical architecture should, in their opinion, be rebuilt as historically correct as possible. In their wake, regionalists advocated the use of local architectural features, but approved the use of modern building techniques behind the facades.

Modernists saw both aesthetic and ethical problems with faithful reconstruction

Modernists’ views were less clearly defined, but they all rejected traditional reconstruction. In fact, it was a discussion that had been going on already before the war. In addition, the modernists saw both aesthetic and ethical problems with faithful reconstruction. Although it was technically possible, modernist critics complained that viewers would never have the same aesthetic experience as they would with a medieval building, with worn stone stairs or weathered sculptures, for example. Modernists also disagreed on ethical grounds with this approach to history. Reconstruction along the lines of the prewar model meant striving for a historical continuity that no longer existed as a result of the war. [4]

Despite all the plans and preparations, however, the postwar reality was beyond anything that could have been imagined. Many municipalities were officially one hundred per cent destroyed and therefore only still existed on paper. Yet a few years later that cheerless wasteland would have a new face. [5]

Laws on reconstruction

Two laws formed the most important legal framework for reconstruction in the Westhoek. The Legislative Act of 23 October 1918 on the right to compensation bound the Belgian state to restore damaged property to its original state. This meant that war damages were settled with each owner separately. As a result of this fundamental principle, overall restructuring across the boundaries of different parcels was more or less excluded. The basis for reconstruction was the prewar property situation, so the idea of building new town centres was replaced by urban beautification.

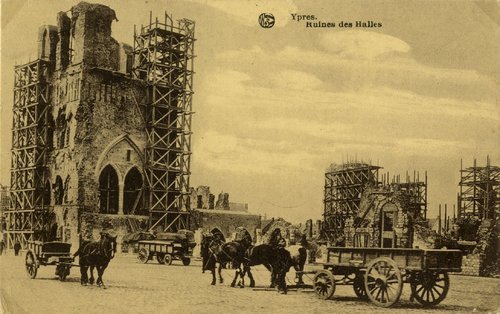

The Ypres Cloth Hall under construction in 1919

The Ypres Cloth Hall under construction in 1919© Westhoek Verbeeldt

The second law that significantly influenced reconstruction was that of 8 April 1919 on the adopted municipalities. Municipalities could have themselves ‘adopted’ if at least ten per cent of their buildings had been destroyed and there were no financial resources to repair the damage. To enable smooth administrative and financial implementation of the law, a special service for the devastated regions, called the Dienst der Verwoeste Gewesten, was set up. [6] Of the 95 municipalities in the Westhoek, 71 were adopted. [7] As a result, local governments were no longer responsible for the organisation of the reconstruction, instead High Royal Commissioners were in charge of approving both the budgets and the building and street plans. It was this same High Commission for Reconstruction that appointed Huib Hoste as the town planner and architect for the municipalities of Zonnebeke, Geluveld, Beselare, Wervik and Geluwe. [8]

Influence of Dutch modernists

Modernist architect Huib Hoste (1881-1957) in the 1920s

Modernist architect Huib Hoste (1881-1957) in the 1920s© Fonds Huib Hoste, Sint-Lukasarchief, SOFAM - België

Hoste can be considered as a pioneer of modernism in Belgium. Born in Bruges on 6 February 1881, he grew up in a traditionally French-speaking and strictly Catholic environment. Neogothic and eclecticism characterised his early years. However, even before the First World War, he was captivated by Dutch modernist architecture. When he fled to the neutrality of the Netherlands during the war, he became completely immersed in it. There he got to know the work of his colleagues Berlage, Van ’t Hoff, Kramer and De Klerk and artists like Van Doesburg and Mondriaan.

In 1916, while he was still in exile, Hoste designed the Belgian Monument in Amersfoort, a memorial from Belgian refugees to thank the Netherlands. [9] It already featured the linear idiom and the importance of volume that were the basis of his later creations. He introduced a cubist style into Belgian architecture, in which new materials such as glass, steel and concrete were essential. [10] Hoste started experimenting with form and colour, whereby abstract planes predominated. Rather than decorative details being used on facades, the facades themselves were decorative. [11] The furniture had to be integrated into the whole, as well. [12]

The Belgian Monument in Amersfoort, designed by Huib Hoste

The Belgian Monument in Amersfoort, designed by Huib Hoste© Wikipedia

In 1920 Hoste designed a store in Wervik. IJzerhandel Vandensteene – Plancke was the first shop building to have a concrete frame. The premises were symmetrical and soberly built. Two years later we could see the same symmetry in a row of houses in Roeselarestraat (9-19) in Zonnebeke. Hoste also drew up an urbanisation plan, the local school with a house for the headteacher and the church with a presbytery. [13]

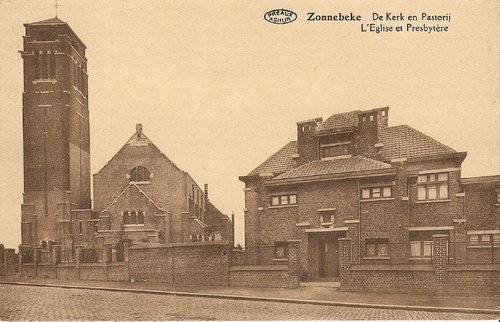

The Church of Our Lady in Zonnebeke is considered to be the first modernist church in Belgium. However, despite the use of reinforced concrete and the cubist idiom, the church has much of the traditional hall churches. [14] A hall church is one with a nave and a couple of side aisles. In Zonnebeke, too, we find a nave and two side aisles, although Hoste transformed the latter into passageways. The Catholic faith and an awareness of Flemish nationalism continue, even later on, to be a latent presence in his designs. Together they form a traditional undertone in his modernist treatments. [15] But in terms of idiom and plan this church would likewise be quickly supplanted. [16]

The Church of Our Lady and presbytery, Zonnebeke, ca. 1932

The Church of Our Lady and presbytery, Zonnebeke, ca. 1932© Westhoek Verbeeldt

No cubism and no Hollandism

Nonetheless, Hoste’s importance as an innovator should not be underestimated. The correspondence in 1922 between Pastor Delrue van Geluveld and Huib Hoste proves that many people were just not open to his new concepts. ‘We asked you for a gothic church, i.e. our fatherland gothic, like everywhere else. Here, as in other places, you have stuck to your own idea and come up with cubism and Hollandism. Well, we’ll have none of that! As men of God, we do not want a second Zonnebeke. We want a triangular choir, porch and frontal facade with three large windows, a tower with a steeple and not a stone oven, a nave not a barn, not even from the outside.’ After repeated modifications Hoste’s design was refused. Jules Coomans, the town architect of Ypres, took over the job. [17]

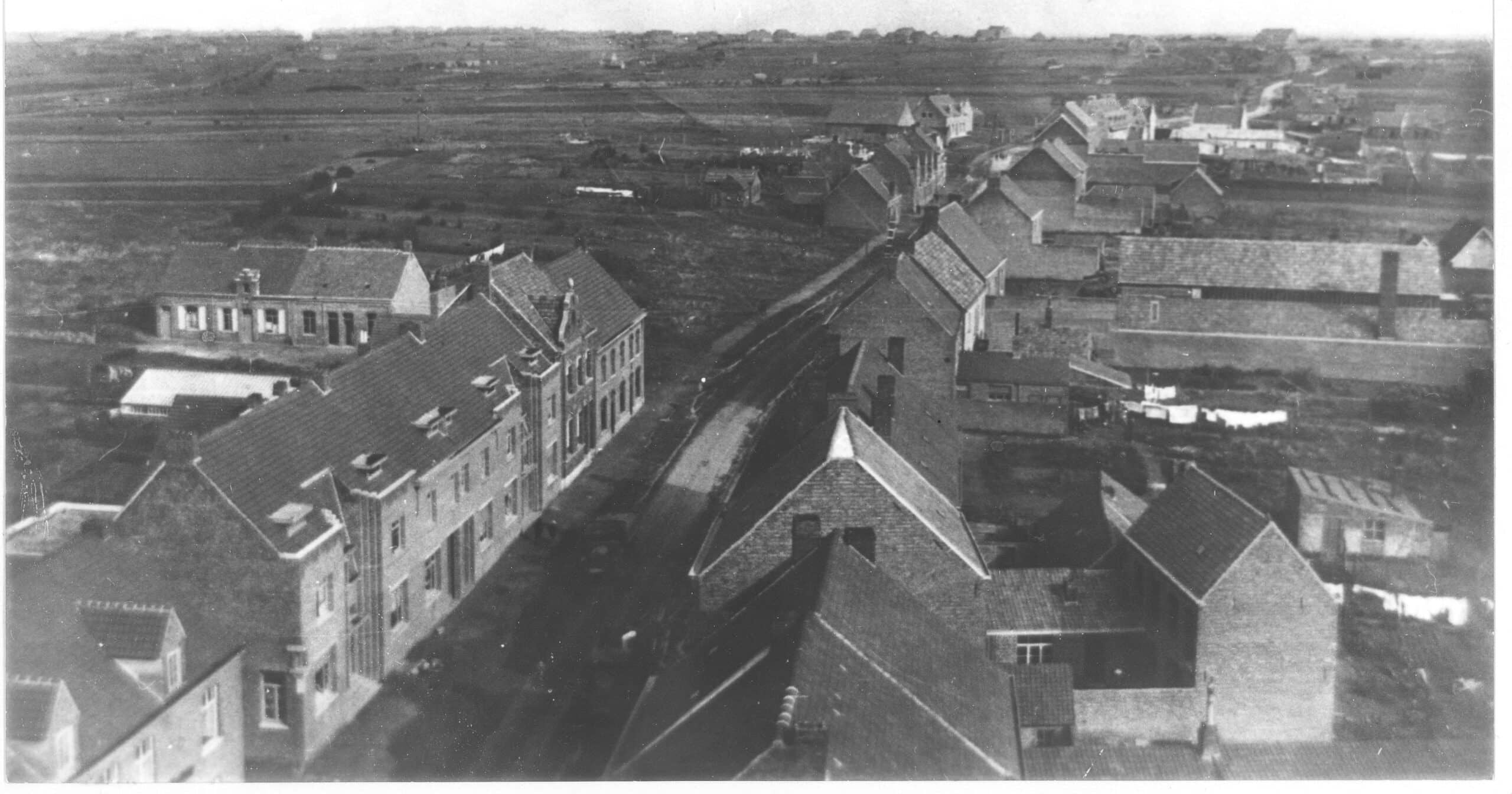

Aerial photo of the Roeselarestraat with row of houses, designed by Hoste, Zonnebeke, anno 1924

Aerial photo of the Roeselarestraat with row of houses, designed by Hoste, Zonnebeke, anno 1924© De Zonnebeekse Heemvrienden

Because most buildings in the frontline towns eventually all had the same external characteristics as before the war, we refer to ‘reconstruction style’ or ‘new old’. Yet it would be wrong to suggest that the Westhoek was rebuilt identically. Often it is the well-known public buildings that were reconstructed to look identical. Some buildings were never rebuilt, were corrected or were built in a different location. In this case, regionalism dominated, but it is, by definition, only a ‘facade architecture’. Behind the ‘old’ facade there is a modern interior built with new materials. Modern architecture, with Huib Hoste as its best-known proponent, contrasts starkly with the ‘reconstruction style’. However, this innovative building style was only implemented sporadically. [18] ‘The few isolated examples of modern architecture that were built, rari nantes in gurgite vasto, for almost all of which we have Hoste to thank, prove that, if people had wanted to, we could have built something beautiful, something real, something new, something perfect.’ [19]

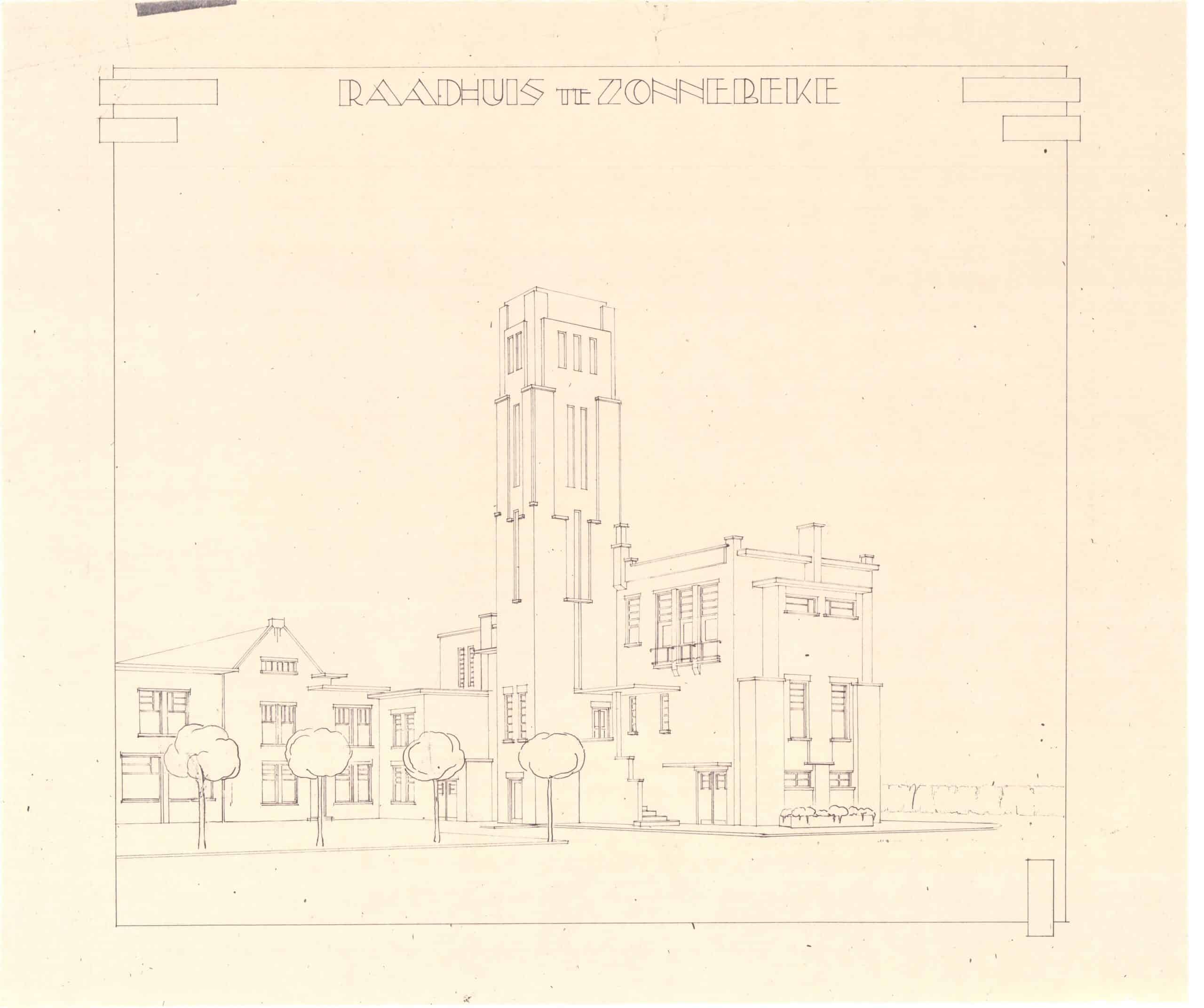

The 1920s were turbulent years for Hoste. He left the building site of the church in Zonnebeke early, after a fatal accident and a dispute with the local council. His exceptionally modern design for the town hall was rejected. A sloping roof was put on the presbytery, which had been finished in 1929, because the flat roofs leaked. [20]

Hoste's exceptionally modern design for the town hall was rejected

Hoste's exceptionally modern design for the town hall was rejected© De Zonnebeekse Heemvrienden

Yet at the same time Hoste acquired (inter)national renown. He was given an award for his design for a ‘study-cum-smoking room’. In 1927 he obtained a professorship at La Cambre, the renowned architecture and visual arts school founded by van de Velde. A year later he was present at the creation of CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne), the most important forum for modern architecture. But, just as his career was taking off, another fatal accident occurred on a building site in Bruges and it stalled. Hoste moved to Antwerp, remaining true to his ideals, but never received the same recognition again. [21] ‘I aroused a good deal of interest and a lot of curiosity, but that was about it.’ [22]

In the Westhoek, 2020 is the Year of Reconstruction. Various partners in the region are working together to develop a comprehensive programme of exhibitions, events and routes to immerse visitors in the story of the reconstruction on some iconic sites in the Westhoek. In Zonnebeke the focus is on the unique story of the architect Huib Hoste.