Wessel Verrijt’s Structures Are Always on the Road

Like his (mobile) installations, Wessel Verrijt seems to be moving endlessly. The artist from Eindhoven is always in-between residencies, performances and exhibitions. Whenever he arrives somewhere, he immediately erects a new work on-site, often recycling discontinued pieces, manifesting in a refreshing DIY aesthetic.

A group of young men is moving small carts along the street, packed to the brim with pallets, bits of plastic and something most closely resembling a blanket. The mere act of watching the procession while trying to deconstruct what is being transported is a joyful activity. A sense of old-fashioned gloating is hard to suppress: the carts’ contents often balance precariously in place or fall off entirely, upon which the journey needs to be temporarily paused.

It is 2016, and the artist Wessel Verrijt (Lierop, b. 1992), then still a student, is moving materials from his backyard studio to the Temporary Art Centre (TAC) in Eindhoven. The move, which lasts approximately an hour and a half, doubles as a performance – an artwork in itself called Het Verrijtbaar Museum (which loosely translates as Het Verrijtbaar Museum (The Moveable Museum) while playing on the artist’s surname). A condensed registration can be found on the streaming site Vimeo. The title is a quip: the artist’s main objective is the collecting itself, not the registration or preservation. This journey will become an important moment in his artistic development: after this, travel becomes an integral part of his artistic practice.

Carnivals and fairgrounds

It is easy to explain things in hindsight – Verrijt readily admits it – but two childhood fascinations can be traced back to his practice: fairgrounds and the carnival. Born and raised in Lierop, the artist describes both events as highlights in his small Brabant village. As a child, he would come to watch their construction and was struck by how snug the attractions would fit into the vans, both upon arrival and departure. It was not until much later that he realized how much this process was reflected in his own methods of tying materials and artworks onto his cart, journeying to the next destination.

Two childhood fascinations can clearly be traced back to his practice: fairgrounds and the carnival

The temporary character of his work bears a strong resemblance to the parades of his youth: a collection of audio-visual impressions that would hit the viewer even before coming around the corner. As an image, the parade exemplifies a state of movement and transience, making it a natural source of inspiration for Verrijt, whose work embodies both characteristics. Once broken down, his artworks are recycled, almost like a methodology of collaging. For the artist, this impermanence is a source of beauty, because it demands a more attentive spectator.

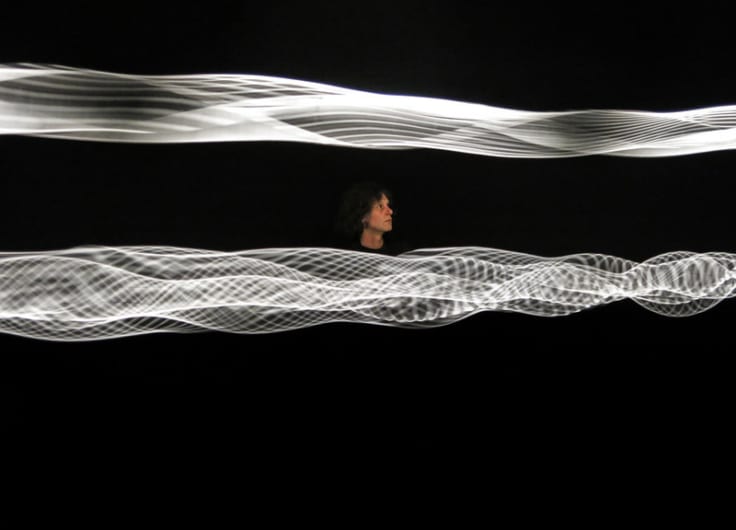

Parade of the Autonomous, Graduation Show AKV St. Joost, ’s-Hertogenbosch, 2018

Parade of the Autonomous, Graduation Show AKV St. Joost, ’s-Hertogenbosch, 2018© Wessel Verrijt

While at the St. Joost art academy in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Verrijt started to build installations using materials found on the street and in garbage bins: pieces of cardboard and textiles for example, but also gardening tools. It all started when he found a plank partially covered in pink wallpaper, littered with scratches. As an object, it immediately inspired Verrijt: what was the story behind it? Under no circumstances would he consider smoothing the paper, which would erase the object’s original purpose, however suggestive. By using discarded materials Verrijt imbues his art with a fresh charm that is rough and material-focussed, in an era when art is often presented in HD on smooth digital screens.

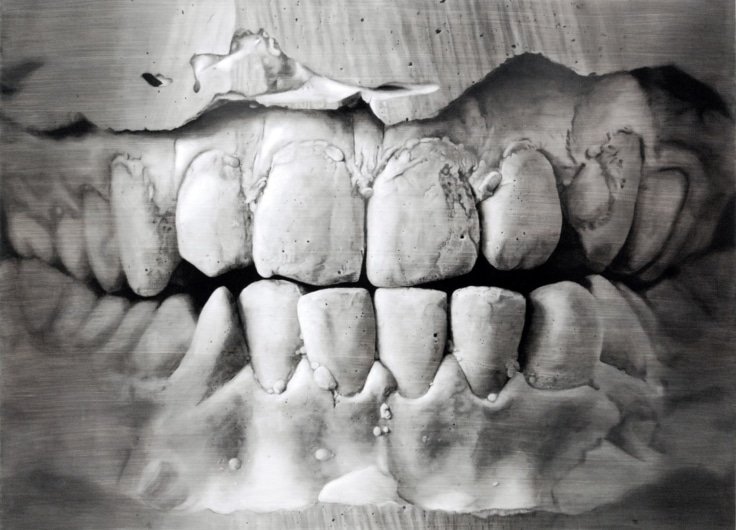

Wooden Parakeet, group show, Temporary Art Centre, Eindhoven, 2020

Wooden Parakeet, group show, Temporary Art Centre, Eindhoven, 2020© Wessel Verrijt

Before long, his collections and installations outgrew the artist’s first studio. Verrijt started building a larger workspace in the academy; a studio that could double as an installation, as well as a background for performances. This being a temporary structure, Verrijt soon found himself looking for a new space within the academy, which, in turn, also needed to be torn down. This ceaseless repetition of construction formed the basis for what Verrijt calls the fundamental narrative of his artistic practice: that of a wandering artist, travelling continuously between residencies, performances and exhibitions. This life of variation, however, offers a myriad of opportunities to find new discarded materials.

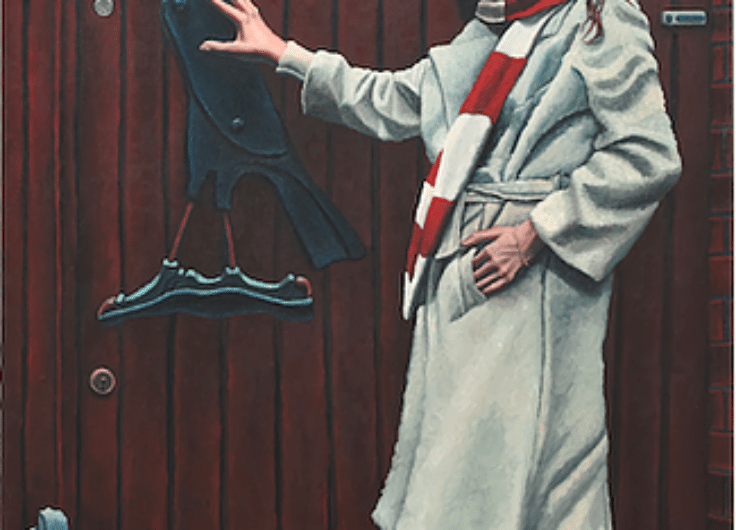

Film experiment, Studio Hemelrijken, Eindhoven, 2020

Film experiment, Studio Hemelrijken, Eindhoven, 2020© Wessel Verrijt

Do It Yourself aesthetics

Verrijt’s oeuvre can be roughly divided into two parts, both offering a varying degree of installation and performative elements. On the one hand, he presents large, ramshackle installations that fill the gallery space and can be moved by the artist or others through controlling certain mechanisms. The Wall Crusher (2019) is a robot-like figure that, by moving its arms, slams pots and pans together much like a crab moves his claws. The movements give the work a clear theatrical and performative element. These types of installations get their compelling presence from their DIY aesthetic. The Wall Crusher holds your attention because it can’t live up to the promise of its title – you expect the machine to fall apart before it can take down the wall.

The Wall Crusher, group show, De Fabriek, Eindhoven, 2019

The Wall Crusher, group show, De Fabriek, Eindhoven, 2019© Wessel Verrijt

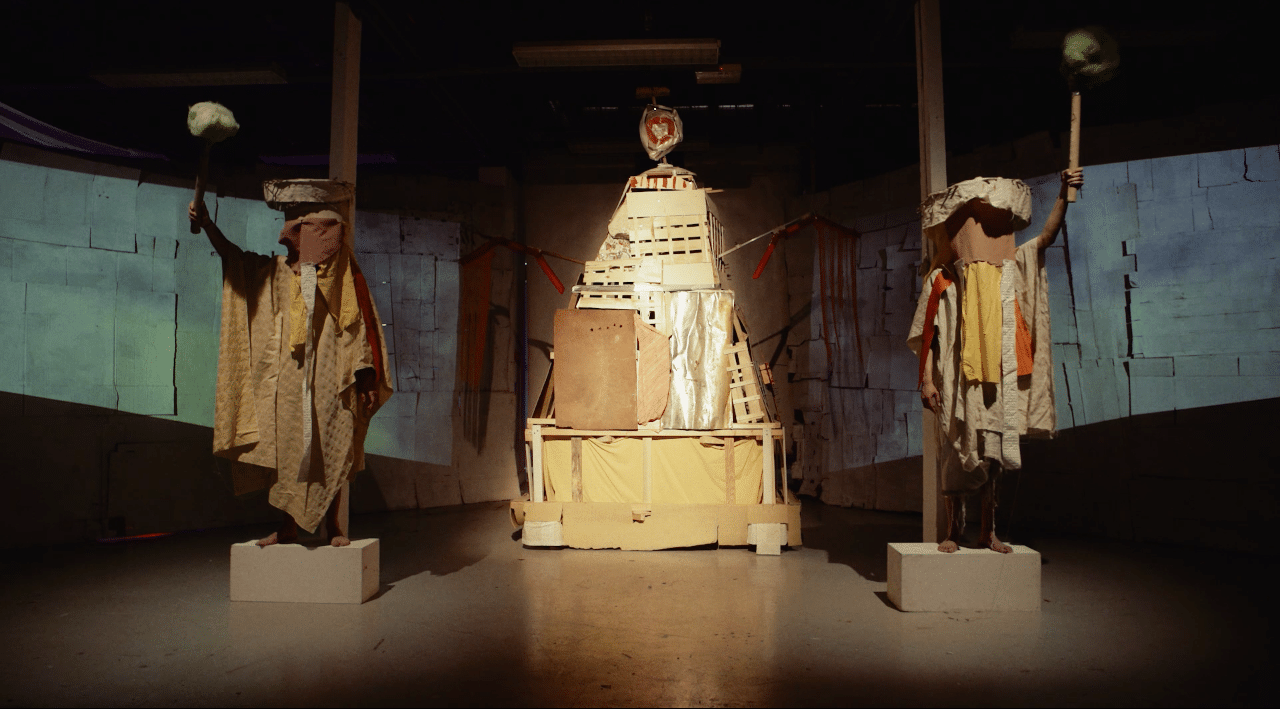

The other part of Verrijt’s practice encompasses the carnivalesque parades for which the artist and his friends dress up in strange, sometimes knight-like outfits that are installations in themselves. These medieval fighters have fascinated Verrijt since his youth, drawn from the Grail Knights of Monthy Python and the titular hero of Floris. The latter makes an appearance in one of his installations.

The Procession, Nijmegen Art Night, Derde Wal, 2019

The Procession, Nijmegen Art Night, Derde Wal, 2019© Wessel Verrijt

For The Procession (2019) Verrijt put on a cardboard harness. Because of the limits, they put on a person’s visibility, movement and navigation, these constructions often do not make the finish line – they are clearly not meant for the battlefield.

Where his installations, within the enclosed space of the gallery, invoke worlds of their own, Verrijt’s knights seem lost in the world outside. However, those who encounter them might wonder where they came from, and potentially feel inclined to assign meaning to their origin stories and goals, contributing in this way to the larger narrative they belong to.

Maintaining legacy

Storytelling is at the core of Verrijt’s oeuvre, and the above elements give insight into the artist and his inspirations. He talks about Jan Švankmajer (1934), the Czech (animation) director whose work was highlighted with a major retrospective at the Eye Film Museum in 2018. By presenting that much work simultaneously, the director’s obsessions and interests were put into context; increasing the power of each individual film or work. For Verrijt it is challenging to approach his oeuvre in this way, as a whole, because its nature is more fleeting than it would have been had he been a painter or sculptor. Although he values this temporary element, he also values results. It remains painful to break down an installation.

Photography proved unable to properly document the kind of spatial and moving work Verrijt produces. Partially because of that he has started to dedicate himself more to video as a form of preservation and a way to shape his portfolio. Where the registration of The Moveable Museum

was produced using documentary strategies, his recent videos have been consciously designed to be works in their own right, incorporating music and montage. In Floris & Sindala (2019) he even uses stop-motion techniques. As a medium, video allows Verrijt to direct the viewer’s attention, which he finds interesting and wants to keep exploring. This makes sense, because what is video but a parade of images?