A World First in Rotterdam: Museum Boijmans Opens Its Entire Depot to the Public

Rotterdam is a world first with Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen: the first fully accessible art depot of a museum. The Depot is not only interesting as a special experience and architectural icon, but also as a serious answer to the question of the legitimacy of museums.

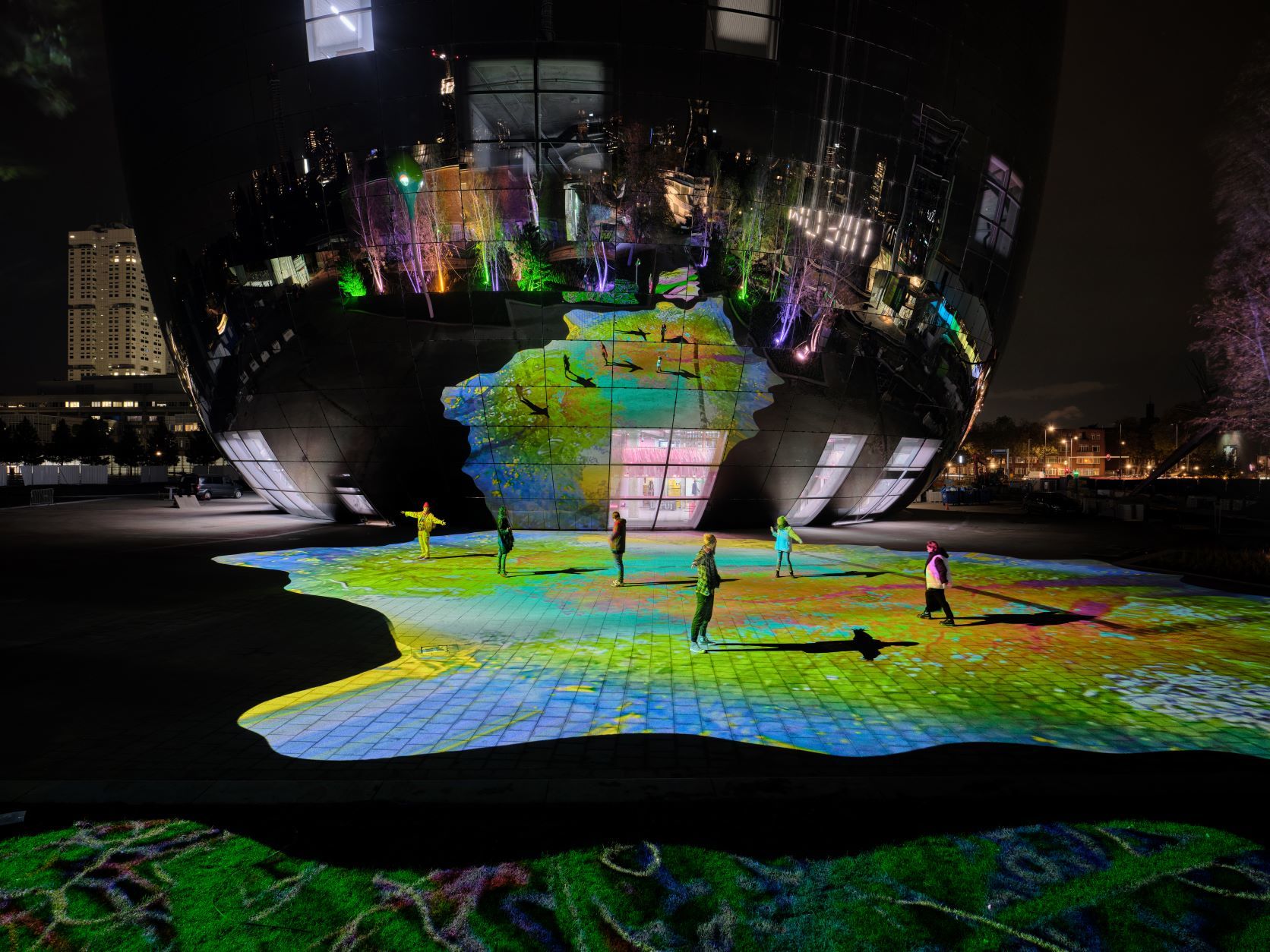

After De Zwaan (Erasmus Bridge), De Koopgoot (Beurstraverse), Het Potlood (Blaaktoren) and De Flipspuit (Hofplein Fountain), Rotterdam now has De Pot. The fact that Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen’s new depot building already has a popular nickname before its official opening indicates that it has been fully embraced by the local population. This is evident from the thousands of selfies taken in front of the building’s mirrored facade in recent months. Furthermore, when the doors opened for a long weekend in September last year for a preview, the seven thousand tickets available were sold out within three hours. Visitors who had managed to get a ticket returned home wildly enthusiastic.

The depot during a preview in September. The people of Rotterdam nicknamed it "De Pot".

The depot during a preview in September. The people of Rotterdam nicknamed it "De Pot".Ⓒ Aad Hoogenboom

Director Sjarel Ex

Director Sjarel ExⒸ Aad Hoogenboom

This has not always been the case. When Boijmans’ director Sjarel Ex first presented his plans for the Depot, his plans were dismissed as megalomaniacal and wasteful. Nature lovers opposed construction in the Museumpark, especially because 255 acacias had to be cut down. The Rotterdam Council for Art and Culture issued a negative advice twice because it considered the plans to be insufficiently elaborated in terms of content and finances. In the city council, there were heated debates about the costs, which turned out to be higher than estimated.

The final price came down to 92 million euros, which is not outlandish for such a project. At least it’s a lot more reasonable than the 259 million euros that the Boijmans’ remodeling and renovation is now estimated at. And that’s where it all started. The construction of the Depot is not a prestige project of an almost-retired director who wants to score one last time, but it is a bitter necessity. The old art storage in the museum’s basement was moderately secure, and when it rained excessively, water gushed in. In 2016, the archaeological exhibit even had to be evacuated. But by then, the vast majority of the collection was already safely housed in five depots across the Netherlands and Belgium.

All the misery was forgotten after King Willem-Alexander opened the Boijmans Depot on November 5th. An event fitting of a royal touch. After all, it is a worldwide premier: the opening of the first fully accessible art depot in the world. And with that Boijmans goes beyond other museums. In order to visit the Sammlungszentrum of the Swiss Nationalmuseum, for example, you have to make an appointment. Schaulager in Basel only gives visitors an idea of the storage space available, but doesn’t let them in. In addition, in the V&A East, where from 2024 onwards the textile and ceramics collection of the London’s Victoria & Albert Museum will be on display, some doors remain closed.

Dutch King Willem-Alexander opened the depot in November.

Dutch King Willem-Alexander opened the depot in November.Ⓒ Aad Hoogenboom

With its revolutionary depot opening, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen addresses one of the most important questions, perhaps the most urgent one, that museums face in the twenty-first century. These institutions were once founded to conserve special objects and preserve them for posterity. For a long time, those treasures were of limited visibility to experts and wealthy patrons. But with the democratization of society, showing and sharing has become increasingly important. In fact, museums nowadays largely derive their legitimacy from interaction with the public, preferably as large and broad as possible.

With its depot opening, Boijmans addresses one of the most important questions that museums face in the twenty-first century

The problem is that the public is not easily tempted by launches of collections. Temporary presentations with spectacular loans or new work are much more popular. The “art hoarding” and the desire for blockbusters to boost attendance figures and keep subsidiary providers happy may make the museum visible, but not the collection. In addition, the aesthetics of the interior have changed over the years so that rooms contain fewer and fewer works.

These trends are illustrated by the history of the Boijmans. When the museum moved into the building at Museumpark in 1935, the entire collection was on display. Eighty years later, only 7 percent of the collection is on display – and with that, the Rotterdam institutions scores no lower than average.

Previously unseen art

With the opening of the Depot, all this unseen art is instantly made available. In a way this is much more exciting than an individual launch of a collection, no matter how bold or grand the setup is. Now the gaze is not directed from image to image in order to convey a specific story, normal practice of a solo exhibition. This means the visitor gets a glimpse into the museum engine room where the meta-story of art collecting is told.

The 151,000 objects that Boijmans collected over 172 years are spread over six floors with five different climate zones for a variety of materials. There are also four restoration studios for photography, textiles, paper, paintings, metal, wood and ceramics.

There are four restoration studios in the depot.

There are four restoration studios in the depot.Ⓒ Rob Becker

There is art everywhere, and it starts right in front of the entrance. It’s where a new video work is projected by Pipilotti Rist, an artist with whom director Ex has maintained a working relationship since his days at the Centraal Museum in Utrecht and who has exhibited several times at Boijmans. Inside the building, art works are wrapped up, in or on racks, but also displayed openly. Prints, drawings and photographs are understandably kept in storage to prevent light damage, but those who wish to see them can make an appointment in a separate study room. There is also a room where films can be viewed.

At the entrance visitors are welcomed by video work by Pipilotti Rist

At the entrance visitors are welcomed by video work by Pipilotti RistⒸ Ossip van Duivenbode

Thirteen display cases for temporary mini exhibitions are up in the atrium. They almost seem to float, making the art seem to become part of a magic show. The eye-catchers are best seen from the stairs that cross the interior space and give the interior a high level of Piranesi.

The display cases for mini exhibitions almost seem to float

The display cases for mini exhibitions almost seem to floatⒸ Aad Hoogenboom

The museum’s collection is not the only thing that is stored and displayed at the Depot. Fifteen percent of the 15,000-square-meter floor area is rented to companies and individuals. KPN, which has one of the oldest and most interesting corporate collections in the Netherlands, is among the first customers. Rental income and sale tickets (adults pay 20 euros) are an important part of the operating model. The Depot will largely pay for itself over a period of thirty years.

Camouflage

An innovative concept deserves an innovative form, and for that Boijmans went to the right person: Winy Maas. In his own words, the MVRDV architect has “made a building that looks like nothing”. In any case, he stayed far away from the traditional depot form: a blind and uninviting box. The Depot is the opposite: modest despite its size and light appearance and charisma. These qualities are largely due to the 1664 mirror glass panels with which the facade is covered. They reflect the surroundings, and make the building blend into its surroundings, almost like a form of camouflage.

The trees on the roof have the same effect. The 75 birches and 25 pines have been raised to withstand the wind at 34 meters, and an ingenious irrigation system keeps them in top shape – at least they look better than the sickly acacias that were cut down for construction. Viewed from above, the vegetation on the rooftop continues into the park. Back at ground level, the connection to the surrounding greenery is maximized by the narrow base of the bowl-shaped building. The Depot has a literally small footprint.

There are 75 birches and 25 pines on the rooftop terrace.

There are 75 birches and 25 pines on the rooftop terrace.Ⓒ Ossip van Duivenbode

Rotterdam – called “the largest sculpture park in the Netherlands” by Winy Maas – has gained an architectural icon with the Depot. It is also interesting for the non-art lover: on the roof there is a restaurant where you can dine or have drinks with a lovely view. The long tables, designed by interior designers from Concrete, can be folded to create an impressive event space.

Those who enter the terrace and walk around will sooner or later find themselves facing the Boijmans museum tower, which is exactly the same height. That view is a reminder that the museum will remain closed for at least another seven years, leaving a significant hole in the cultural program of a rapidly growing city that is always hungry for more. In that respect, the opening of the Depot has come not a moment too soon.