Before the Architect Came the Painter: Henry Van de Velde as a Visual Artist

As an architect he became famous throughout Western Europe. But what about Henry Van de Velde’s previous career as a painter? From a new and hefty catalogue raisonné emerges the picture of an artist who struggled with social status and innovation in his craft.

Anyone who has ever seen a retrospective of Belgian art may know that the famous architect Henry Van de Velde was once also a painter. Exhibitions generally display his best-known pointillist work: Bathing Huts at Blankenberge (1888), which resides normally at Kunsthaus Zurich. It is without question a relevant work – the French artist Paul Signac regarded Van de Velde as a pioneer of neo-impressionism.

Bathing Huts at Blankenberge

Bathing Huts at Blankenberge© Kunsthaus Zürich

But he was not an early innovator of pointillism, and a new catalogue raisonné published with Ludion by the gallery owner and collector Ronny Van de Velde shows that the French-speaking Antwerper hardly clung to ‘cold’ pointillism for the rest of his short painting career. His later dune landscapes with their arced lines drawn in various pastels may be just as important as his pointillist works, especially in light of Van de Velde’s role as a pioneer of Art Nouveau.

Today we are inclined to assume that the arabesque line or the so-called whiplash motif are autonomous features of Art Nouveau style. But artistic contemporaries of Henry Van de Velde have never doubted that the novice designer inherited these lines from his time as a visual artist. Art historian Xavier Tricot, who introduced and edited the catalogue raisonné, cites Henry Van de Velde’s description of “le démon de la ligne” – a demon that never left him, even after he gave up painting in 1893.

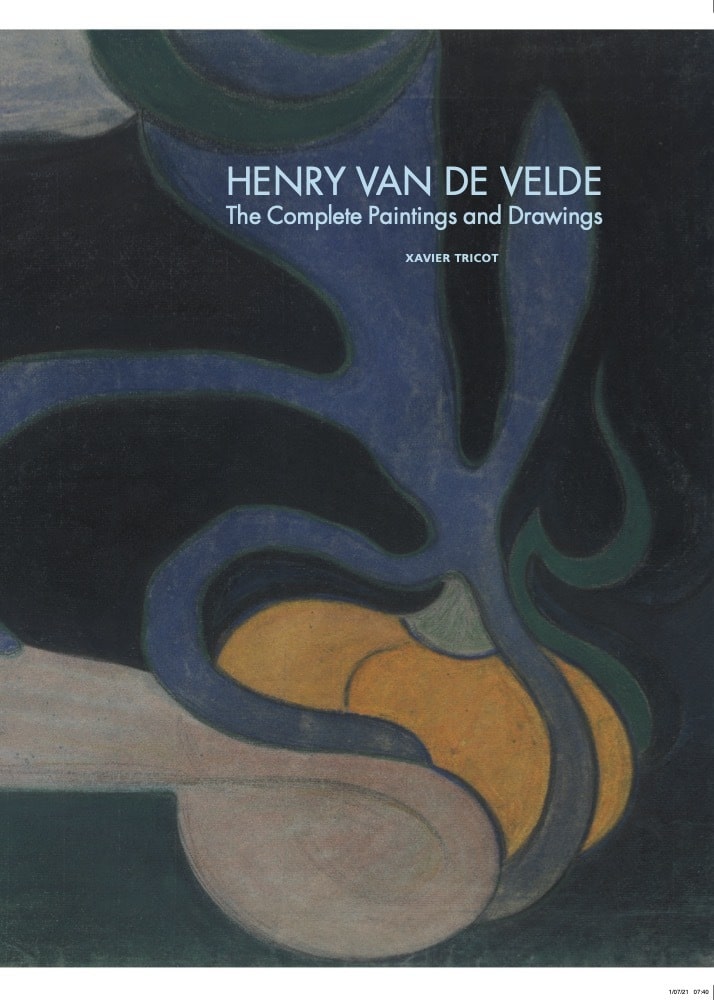

Cover of the catalogue raisonné

Cover of the catalogue raisonné© Ludion

The catalogue raisonné starts with his earliest works in 1882 and documents some sixty paintings and two hundred drawings and pastels. In order to paint a clearer picture of the development of the painter and how other artists influenced his style, we shall proceed chronologically.

This means going all the way back to September 1880, when the seventeen-year-old Henry Van de Velde enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp. His father, who ran a pharmacy on Falconplein, was surprised the second youngest of his eight children did not pursue music. Music had always interested the young man, and father Guillaume was the president of the Société de Musique d’Anvers. Still, the young Henry must have exhibited a material talent even then, because the oldest of his preserved oil paintings – landscapes featuring barns and mills – transcended the niveau of a dilettante.

According to Van de Velde, the Academy building had a suffocating and discouraging influence on generations of artists

From Van de Velde’s memoirs (Récit de ma vie) we know that he did not have the best memories from his time at the Academy (1880 – 1883). He compared the poorly lit and badly ventilated studios of the academy with the halls of a “hospice” and to barracks. According to Van de Velde, the building emanated “deathly boredom” and had a suffocating and discouraging influence on the generations of artists who studied there.

In the summer months he would escape to Kalmthout, where he captured the heath landscapes and outdoor life in his work. In his final year he also received private lessons from the Academy director Charles Verlat, but this did not noticeably influence the artist’s style.

Henry van de Velde painted robust compositions in earthy tones, and peasant life was a favorite theme of his. At the same time, he was also attracted to the lighter work of plein air painters, like those of the Barbizon school in France and the Tervuren school in his own Belgium. These painters would go out with their field easles to capture the play of light at a particular time of day. But as was typical for the young Antwerp-based artist, he never quite mastered the artistic innovations by which he was inspired. Even when thoroughly impressed by the stark depiction of the barmaid in the famous painting Un bar aux Folies Bergère by Edouard Manet in 1882, Van de Velde forged on studiously in his same old style. Nevertheless, he noted with admiration: “Je subit un choc”, resolving to closely follow the clashes between Manet and the conformists.

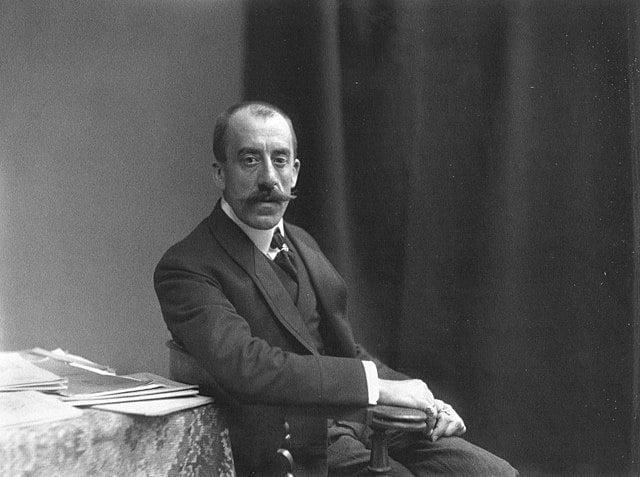

Henry Van de Velde, around 1903

Henry Van de Velde, around 1903© Louis Held, Wikimedia Commons

His own submissions for the Union Artistique des Jeunes in Antwerp, including the portrait of his father, are worthy of recognition, but they are certainly not confrontational works. Henry van de Velde was a co-founder of this art circle, better known for its motto Als Ik Kan – after Jan Van Eyck’s credo. But Van de Velde resigned in 1886 because of their opposition to the Brussels art circle Les XX (Les Vingt), which was a haven for the international avant-garde.

By then he had been living in Kalmthout for two years, and a lightness and spontaneity began to creep into his previously dark and naturalistic style. From 1885 onwards, he began to abandon geometric perspective, which made way for more daring attempts at representing atmospheric depth. Perhaps his exploratory trip to Barbizon in the spring of 1885 was responsible for this shift. During this trip he spent unforgettable hours in the presence of the painter Jean-François Millet, who shared his fascination with peasant life.

Joseph Heymans

In February, Van de Velde moved to the Kempen region, where he lived in the village Wechelderzande in a room above the Keizer Inn. There he met Joseph Heymans, under whose influence he transitioned to a looser style with broad strokes. Heymans would go on to pen a letter of recommendation in favor of Van de Velde to Octave Maus, the secretary of Les XX.

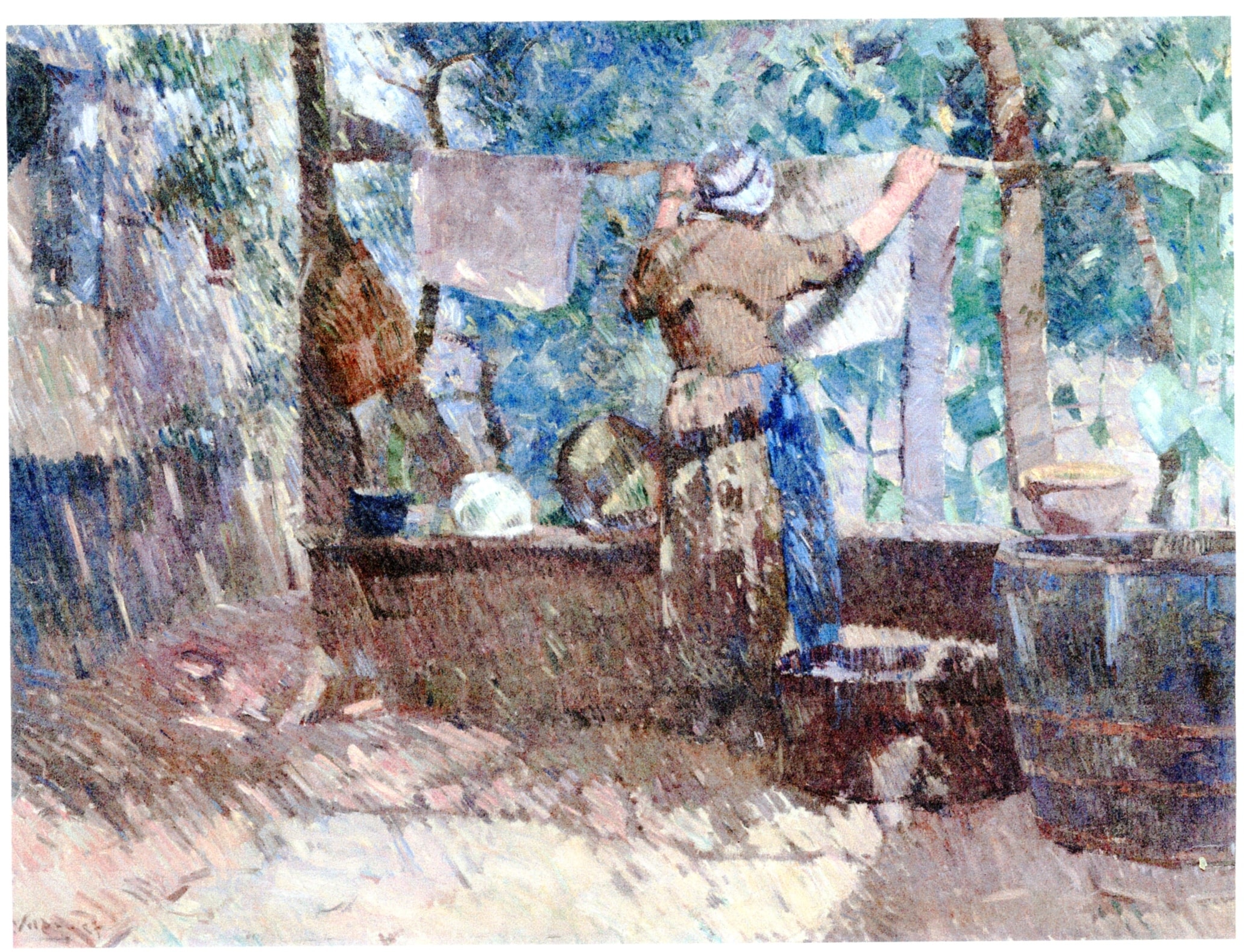

In 1887 Henry Van de Velde went to see the Millet exhibition in Paris, making enthusiastic notes on on every page of the accompanying catalogue. In the wake of this exhibit his own style became more dynamic, featuring thick, nervous brushstrokes and new attention to different shades of light. A fine example of this can be seen in The Washerwoman, in which the sunlight vibrates across the laundry that is hanging out to dry. Using parallel, sometimes overlapping brushstrokes, he also painted the emotional portrait of his terminally ill mother while he cared for her on her deathbed in the summer of 1888.

The Washerwoman

The Washerwoman© Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerpen

Georges Seurat’s pointillist masterpiece Un dimanche après-midi à l’Île de la Grande Jatte blew Van de Velde away at the fourth salon put on by Les XX in Brussels. The dots with which Seurat built the tranquil scene of people relaxing on the banks of the Seine consist of pure colors that only mix upon the retina of the viewer. When he discovered more dot-work by Paul Signac at the next salon, Henry immersed himself completely in color theory and the painting techniques of neo-impressionism. In his memoirs he notes “Je me sentis bouleversé (…) From that moment on, it seemed to me impossible to resist the urge to absorb the theory, rules, and fundamental principles of the new technique in order to experiment with it as quickly and conscientiously as possible.”

But this enthusiasm to throw himself into things was also dampened at times. Henry van de Velde struggled with doubts about the social status and privileges of the visual artist, resulting in periods of apathy interspersed with bouts of hyperactivity. In those more difficult times he found support in Joseph Heymans and, during Sunday meetings in Brussels, from the art patron and lawyer Edmond Picard, one of the driving forces behind Les XX.

When Henry Van de Velde was elected a member of Les XX in 1888 together with Auguste Rodin and Georges Lemmen, he resolutely took the step towards neo-impressionism in his painting practice. Van de Velde submitted six paintings to the exhibition of Les XX in 1889, including his famous work on the beach at Blankenberge.

After his mother’s death in 1888, the painter stayed with his brothers Felix and Laurent in Blankenberge. The dunes and the beach became his main theme, but gradually his faith in pointillism seemed to waver. When Henry van de Velde discovered Vincent van Gogh with his direct, expressive style at the Les XX exhibition around 1890, he was sold once again. He notes that he was left torn between the cold, almost mechanical stippling technique and the passion of direct expression.

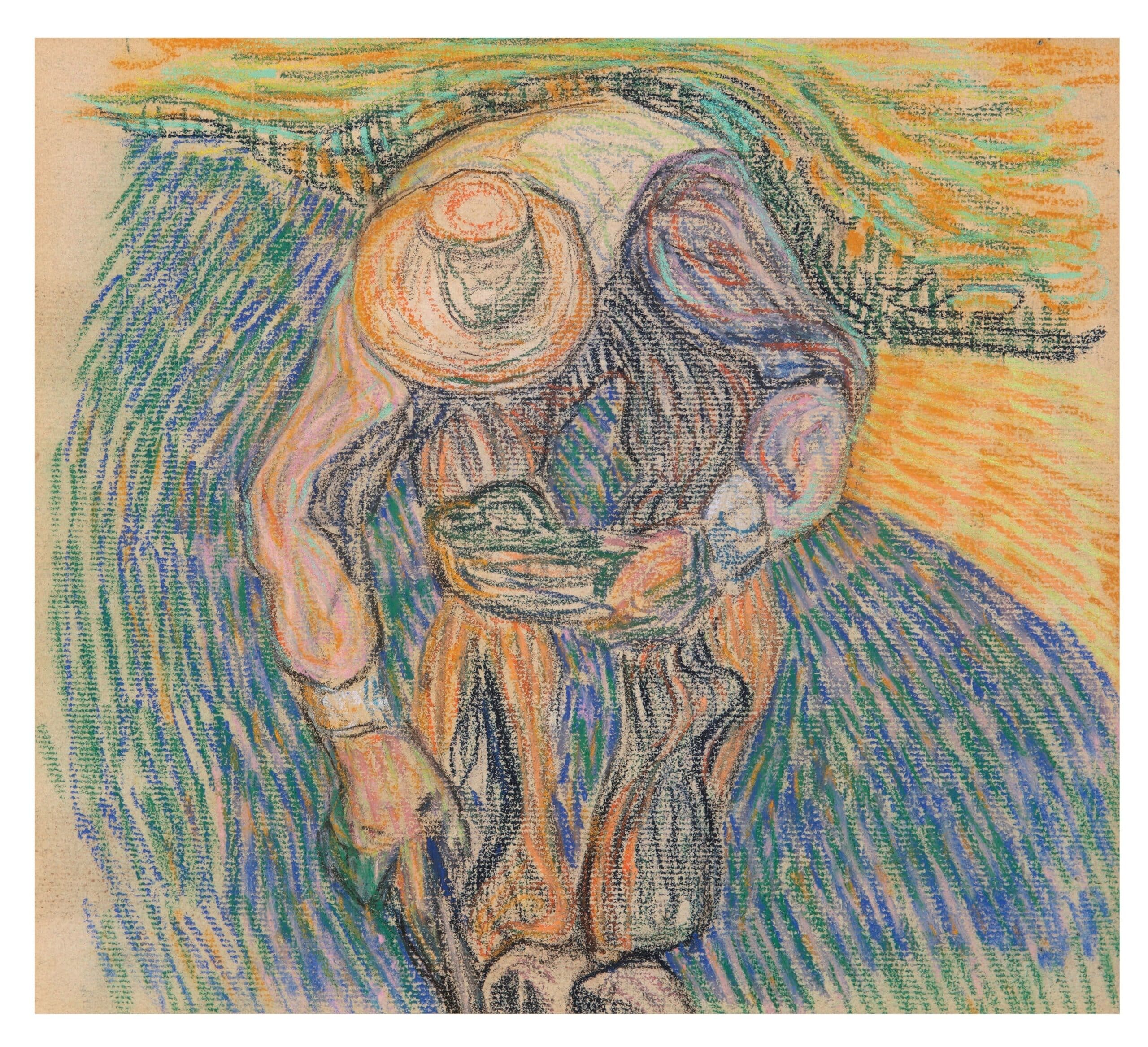

Peasant with straw hat bending

Peasant with straw hat bending© Collection Ronny and Jessy Van de Velde, Antwerp

From 1891-1893, Van de Velde initially played with the effects of light and shadow. But gradually we see Van Gogh’s influence take over in the expressive, uninterrupted lines with which Henry sings about peasant life in oil paints and pastels. This kinship went further than the use of color and expressive brushwork – they also cherished a similar veneration for the harshness of peasant life. During that period Van de Velde wrote an essay on the place of the farmer in art history, and the Dutch artist Jan Toorop, who had been a member of Les XX for some time, convinced Van de Velde to present his lecture Le Paysan en peinture in The Hague as well.

In 1891 Van de Velde and his poet friend Max Elskamp became part of the founding committee of Association pour l’Art in Antwerp, which wanted to shake up a sleepy Antwerp art scene. At the opening of the Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp one year earlier, Van de Velde had already taken a stand against the old-fashioned temple-style architecture. In the magazine L’Art Moderne

he described it as “a docile copy in a so-called neo-Greek style, completely superfluous and worthless”.

After that he often returned to Kalmthout to stay with his sister, where he would visit Villa Vogelenzang on several occasions. The beach and dunes also remained a recurring theme in his pastel studies with striking arabesques. “The beach or dune view is transformed into a decorative pattern,” Xavier Tricot concludes. Van de Velde synthesized nature into an almost abstract interplay of lines, and was in this sense twenty years ahead of Piet Mondrian. But such decorative imagery and graceful lines also dominated in the work of post-impressionists in Nabis and Pont-Aven in that period.

For Henry van de Velde, this phase represented a precursor to his leap into the applied arts. As a painter he was unable to live off his work – his father had subsidized his livelihood for a long time – but in the end it worked out better for him as a designer. After giving up painting in 1894, Henry married the Parisian pianist Maria Sèthe, a woman immortalized still in a dreamy, pointillist portrait by Théo Van Rysselberghe.

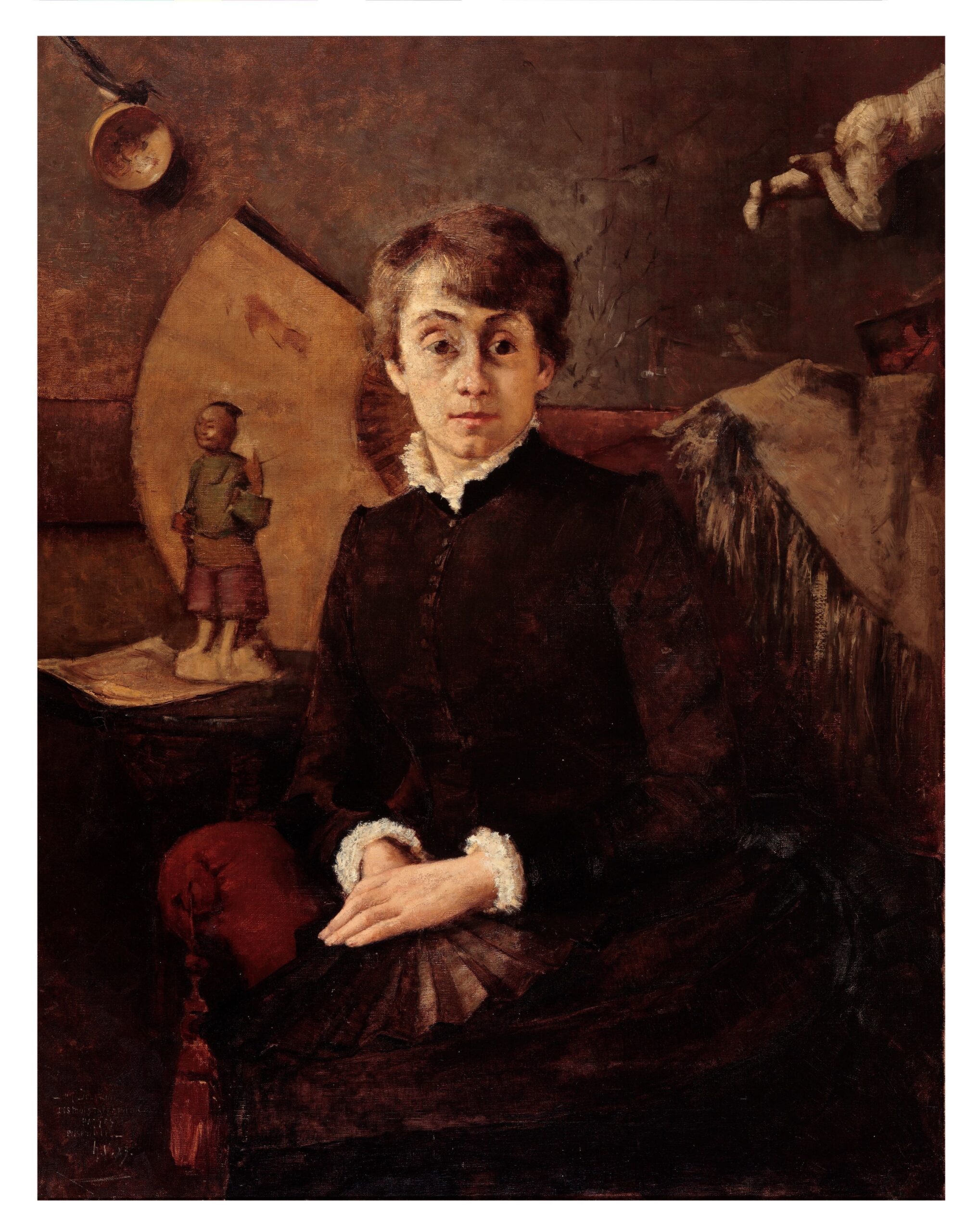

Portrait of Jeanne Biart-Van de Velde, his sister

Portrait of Jeanne Biart-Van de Velde, his sister© Galery Ronny Van de Velde, Antwerp/Knokke

Doubts about his role in society that had hindered him as a young artist disappeared when Van de Velde earned his wings as a designer. With the design of fabrics, utensils, theater sets, furniture and buildings, he had an impact on peoples’ daily lives that he never had as a painter. His mission was to free the world from its ugliness. For him a home is a Gesamtkunstwerk, everything, every ornament and every utensil must breathe harmony and beauty. Ten years after his retirement from painting, Van de Velde became an icon in Germany as the founder of the Kunstgewerbeschule in Weimar and a pioneer of the Bauhaus.

In a foreword to the catalog raisonné, Lisette Pelsers (director of the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo designed by Van de Velde) writes that the architect “never lost his painter’s eye”. In 1921, Henry encouraged his client Helene Kröller-Müller to pursue the acquisition of several Seurat paintings. According to Pelsers, the museum owes a large part of its unique Seurat collection to the architect.

In 1928 paintings by Henry van de Velde were displayed at an exhibition about Antwerp-based painters. In his review, art critic Ary Delen wrote that Antwerp had mistakenly forgotten Van de Velde as a painter. With the recently published catalogue raisonné, Ronny Van de Velde builds a dam against this forgetfulness.