Circus Steals the Show – Made in The Low Countries

The circus scene in the Low Countries is fully embracing new forms and disciplines. The sector is also experiencing strong organisational growth, but at two different speeds. While artists and companies in Flanders receive structural support from the government, Dutch artists are often left to fend for themselves.

The days when the circus meant nothing more than travelling tents and trained bears are long gone. In Flanders and the Netherlands, a shift has been underway over the past few decades, with traditional circus giving way to a contemporary artistic movement. “Circus has undergone a true metamorphosis,” says Noemi De Clercq, director of the Circuscentrum (Circus Centre) in Ghent. “Contemporary circus emphasises artistic expression and storytelling, combining traditional circus techniques with elements from theatre, dance, and music. This has led to the emergence of hybrid forms, such as the work of Alexander Vantournhout, who blends circus and dance into a unique movement language of his own.”

Circumstances, the company of Flemish choreographer Piet Van Dycke, also blurs artistic boundaries. This is evident in the successful production Glorious Bodies, in which he brings together six acrobats aged between fifty-five and sixty-seven to tell a story through circus and dance about the capacity of our body, about seeing and being seen. In his new show Beyond, six artists, each specialising in a different discipline (ladder walking, acrodance, acrobike, partner acrobatics and (pole) dancing), push their limits. “Circus is thriving and is increasingly recognised as a full-fledged part of the performing arts,” says Van Dycke. “Choreographers and theatre makers see the potential and want to collaborate with circus artists.”

Lieke De Vry, through her exchange project Circus ID, created a performance with young people from Palestine and six Belgian studios

Lieke De Vry, through her exchange project Circus ID, created a performance with young people from Palestine and six Belgian studios© Circus ID

Circus can also be a socially engaged art form. In 2023, Lieke De Vry, who recently received the Ultima (the Flemish Culture Prize) for circus, created a production with young people from Palestine and six Belgian studios through her exchange project Circus ID. The company performed the show, among other places, in the West Bank. “Circus ID illustrates how values of inclusion and solidarity can form the foundation for connection across borders,” wrote the jury of this cultural award from the Flemish Community about the project.

Piet Van Dycke (choreographer at Circumstances): 'Choreographers and theatre-makers see the potential and want to collaborate with circus artists'

“The main difference between then and now lies in the form of presentation,” explains Rosa Boon, director of the Dutch organisation TENT, home for contemporary circus. “Traditional circus offers a succession of acts that revolve around technical excellence, whereas the contemporary form has a more dramatic approach.”

Choreographer Alexander Vantournhout and Emmi Väisänen in every_body

Choreographer Alexander Vantournhout and Emmi Väisänen in every_body© Bart Grietens

Broadening the image remains a challenge. “It is clear that the label ‘circus’ is often avoided,” says De Clercq. “Shows might, for example, be billed as a ‘family performance’, which doesn’t really help the perception. The stereotypes around the circus are deeply rooted in our language; think of expressions like ‘playing the clown’ or ‘the political circus’. With a campaign such as #ookditiscircus (#thisisalsocircus), we at the Circuscentrum are trying to promote a more positive and diverse image. Today, there are many subgenres within the circus, just as ‘dance’ is also an umbrella term for hip hop, classical ballet, modern…”

Every city has a studio

Of the traditional tent circuses, eight are still active in Flanders and eleven in the Netherlands. But the contemporary circus continues to grow, with around eighty Flemish and thirty-five Dutch circus companies. These companies and artists don’t come from nowhere. Flemish circus studios, in particular, are now highly regarded. “In Flanders, every self-respecting small town has a studio where children and young people can learn all kinds of circus techniques,” notes Boon. “In the Netherlands, we were ahead of the game fifteen years ago with organisations such as Circus Elleboog, Rotjeknor, Poehaa and Santelli. Sadly, those days are gone.”

A performance by Circus Elleboog (Elbow) in 1950

A performance by Circus Elleboog (Elbow) in 1950© Fotopersbureau De Boer

Circus emerged as a new art form in the last century and simultaneously became a popular leisure activity. Circus Elleboog in Amsterdam, the oldest youth circus in the world, was founded in 1949 and served as a model within the world of youth circuses in the Netherlands (until it was forced to close in 2020 after subsidies were withdrawn). In Flanders, contemporary circus emerged in the 1990s. “An important milestone was the creation of the International Street Theatre Festival in Ghent (now known as Miramiro) in 1990 and the opening of the first circus studio, Circus in Beweging (Circus in Movement), in Leuven (1993). Another key moment was the appointment of Circus Ronaldo as a cultural ambassador of Flanders in 1998,” says De Clercq. “After that, the circus was increasingly embraced by festivals and policymakers, allowing the sector to professionalise.”

“The Dutch youth circus is very pedagogically oriented,” says Dutch circus artist Zinzi Oegema. “It focuses on coordination and cooperation between the children and young people, but doesn’t really train them to advance to a higher level. In Flanders, some studios spot young people with talent, and the infrastructure offers more technical possibilities for the circus.”

In Zinzi Oegema’s Dutch–Flemish production MAT, seven acrobats explore the art of falling

In Zinzi Oegema’s Dutch–Flemish production MAT, seven acrobats explore the art of falling© TENT / Gerrit Schreurs

Despite this strong foundation, Flanders does not have its own bachelor’s degree programme in circus arts. Artists often seek further training abroad, although some go on to the Brussels-based École Supérieure des Arts du Cirque (ESAC). The Netherlands has two programmes, both highly regarded: Codarts Circus in Rotterdam and Fontys Circus and Performance Arts in Tilburg. In their nearly twenty years of existence, they have played a crucial role in professionalising the sector. And, says Boone, Flemish students are always welcome at these programmes, thanks to the high level they achieve when they leave these studios.

“Precisely because it is such an international melting pot, the study programmes are under pressure,” says Boon. “There aren’t enough Dutch students progressing from circus studios to bachelor’s degrees. Those who do become professional circus artists often head abroad. Only in recent years have Dutch artists remained working in their own country more.”

Flemish artists usually return to Flanders after completing their education abroad. “The workshops they attended as children remain a home base, a community,” says De Clercq. “Besides the Circuscentrum, these are the places they first turn to for further support. Then there are the subsidised workspaces – Circuswerkplaats Dommelhof, CIRKLABO, Miramiro and PERPLX – where they are given time, space and guidance to work on their creations. Flanders does not have a university of applied sciences for circus, but it compensates with studios and workspaces. These development opportunities are less established in the Netherlands.”

Training in a sports hall

Another reason why Flemish artists return is the Circusdecreet (Circus Decree), which is also the biggest difference between the circus sector in Flanders and the Netherlands. The decree recognises the unique nature of circus as an art form and offers both project-based and structural financial support (more than six million euros annually) to a support centre, circus workshops, artists, companies, studios and festivals. “By choosing a separate subsidy line, the Flemish government was able to respond to the specific needs of this emerging sector and encourage its professional development. As a result, Flanders is an attractive base for setting up a company and creating performances,” says De Clercq.

The Circusdecreet has been in effect since 2008 and was improved after an evaluation in 2019. This year marks the end of the first policy period (2021–2025) under the amended decree, and in early May, artists and organisations submitted their new funding applications. “The separate financial resources remain essential for a sector experiencing rapid growth,” stresses Piet Van Dycke. “You cannot expect circus artists to immediately progress into the existing arts system. In the Netherlands, there is no separate support for circus artists, and they have to compete within the broader arts funding policy. After I graduated in the Netherlands, I stayed there for a while. But because of the fragmentation of funds, it turned out to be very complicated to obtain financial support.”

As a circus creator, you can obtain subsidies in the Netherlands, but it remains a challenge. Zinzi Oegema applied for support from the Fonds Podiumkunsten (Performing Arts Fund) for new artists, but noticed that it is only recently that the committee has become more aware of circus as a modern art form. “In Flanders, the government has recognised that the circus is a new art form that requires its own dedicated subsidies. This has allowed the sector to gain real momentum.”

Rosa Boon (TENT circus house): 'Traditional circus presents a sequence of acts focused on technical excellence, while the contemporary form follows a more dramatic line'

In addition to financial support, having a central organisation for the circus arts makes a difference. In Flanders, that role is fulfilled by the Circuscentrum. This subsidised organisation – with around ten staff members – is an important link between policymakers and the field. It closely monitors developments, plays an active role in policymaking, conducts research and promotion, and brings the sector together. Its Dutch counterpart, Circuspunt (Circus Point), operates with limited financial resources and relies mainly on volunteers. It focuses primarily on advocacy and lobbying but has fewer possibilities to offer structural support.

The difference in resources and central structure affects the professional development of circus artists. In the Netherlands, for example, training facilities are considerably less extensive. “If you want to train in the Netherlands, you usually have to rent a hall yourself,” says Boon, “whereas in Flanders, travel and accommodation costs are sometimes even reimbursed.” There are a few Dutch talent development organisations, such as TENT, and workspaces like Diepenheim and Circuskapel Den Bosch, but demand far exceeds supply. Moreover, Dutch venues are often not specifically equipped for circus practice. “In Amsterdam, sports halls are often the only option, or you have to rent spaces from other companies,” says Oegema. “In Flanders, there are not only more workspaces, but the youth circuses are also well equipped. I regularly train in Antwerp at the Ell Circo D’ell Fuego studio.”

Growth

Creating new performances is one thing, but where are they shown? Both Zinzi Oegema and Piet Van Dycke have networks in their neighbouring country and regularly go there to train and perform. De Clercq also stresses the importance of cooperation between the Netherlands and Flanders: “The sector is highly international. Flemish companies look to France as a model in terms of policy, infrastructure, and performance opportunities, but in recent years the Circuscentrum has also focused on exchanges with other countries, including the Netherlands.”

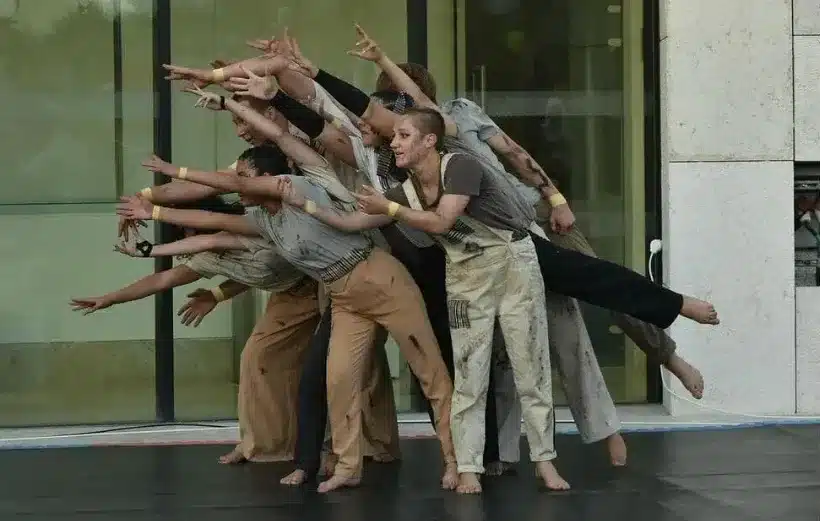

In Beyond by Circumstances, six artists – each specialising in a different discipline (ladder walking, acrodance, acrobike, partner acrobatics and (pole) dancing) – push their limits

In Beyond by Circumstances, six artists – each specialising in a different discipline (ladder walking, acrodance, acrobike, partner acrobatics and (pole) dancing) – push their limits© Jonas Vermeulen / Circumstances

In the Netherlands, there are five festivals dedicated to contemporary circus, including Festival Circolo and Circusstad Festival, as well as initiatives for emerging artists such as Circunstruction in Rotterdam. Flanders boasts a diverse range of venues, with no fewer than thirty festivals placing a strong emphasis on circus, and cultural centres are increasingly programming circus as a fully fledged performing art. “The Circuscentrum regularly organises meetings that many cultural centres take part in,” says De Clercq. “That’s an important step, but we also want to collaborate more with arts centres and festivals.”

In the Netherlands, Oegema also notices that festivals tend to be open to the circus, whereas theatres see it more as a risk. “They have theatre and dance programmers, but hardly any staff who attend festivals to scout new circus productions.” The performances that do manage to secure a spot outside the circus network and thus reach a different audience are often those that intersect with other performing arts. For example, the hybrid productions of Van Dycke’s company, Circumstances, are picked up well by theatres and festivals. “Our work can just as easily be considered dance, which means we perform in many different contexts. We’ve even been on stage at Lowlands, and this summer we’re heading to the Sziget Festival in Budapest.”

The sector in both the Netherlands and Flanders is in full development. Despite the limited resources in the Netherlands, TENT director Rosa Boon is optimistic. “The first artists from the universities of applied sciences graduated about fifteen years ago and are now preparing to perform in large venues. I’m curious to see what that will lead to.”

Flemish productions are already eagerly being programmed abroad. In Flanders itself, all eyes are now on the forthcoming evaluation of the Circus Decree. Piet Van Dycke: “Thanks to the decree, we don’t have to compete with other performing arts. The question then becomes: how can we maintain the sense of solidarity among circus artists now that the sector is growing so rapidly?”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.