Colonial Looted Art: How Museums Are Reckoning with Their Past

How are Belgium and the Netherlands dealing with the thorny issue of restituting looted art and investigating its colonial origins? What do museums reveal — and what remains overlooked? Two encounters offer a glimpse of the debate: one with public relations officer Nadia Nsayi at the AfricaMuseum in Tervuren, and another with content director Wayne Modest at the Wereldmuseum in Amsterdam. “It is shameful to display these riches without mentioning colonial plundering.”

It could hardly be more clinical. A twenty-metre-long dugout canoe, carved by hand from a Sipo tree, stands in a brightly lit, white basement corridor. This is where visitors to the AfricaMuseum in Tervuren begin their tour of the imposing royal Colonial Palace. The almost total lack of context turns the utilitarian object into an abstract form reminiscent of a modern work of art, torn from the river of time. On the wall behind it is the intriguing, much-quoted text, “Everything passes, except the past.” The canoe, which comes from a village on a tributary of the Congo River and was shipped to Belgium in 1958, is unmoving.

The large canoe in the AfricaMuseum in Tervuren, with the text on the wall in four languages: “Everything passes, except the past.”

The large canoe in the AfricaMuseum in Tervuren, with the text on the wall in four languages: “Everything passes, except the past.” © Collectie AfricaMuseum

So, how did this huge canoe end up here? The sign on the wall states that, according to the museum archives, it was “made by the inhabitants of Ubundu on their own initiative, as a gift for the former monarch (Leopold III, KW)”, but that “the question remains whether it was commissioned by the colonial administration.”

Spontaneous action

Anyone who takes the trouble to scan the QR code on the pink provenance sticker next to it can read a more detailed story on the museum’s website that makes a spontaneous action by the local population seem very implausible. Before the World Exhibition in Brussels, in 1958, the then museum director, Frans Olbrechts, arranged for the local colonial administration to send a dugout canoe, in which King Leopold III had travelled through Congo a year earlier, to Belgium. On its arrival, it was recorded as a gift from a Mr Van Elsen, the deputy territorial administrator of Ponthierville (Ubundu). The following has been added in bold letters, “Although Van Elsen mentioned the important role of the village chief in making a canoe like this available, he gave no information about discussions or transactions with the Congolese regarding the provision of the canoe for Leopold III.”

As a visitor, how should you interpret this? As legal cover for the museum against restitution claims? Or as an acknowledgement that there was more at stake than just the reality on paper?

Nadia Nsayi of the AfricaMuseum: “African artists are being used to aestheticize and tone down politically sensitive issues.”

Nadia Nsayi of the AfricaMuseum: “African artists are being used to aestheticize and tone down politically sensitive issues.” © Noura Kaddaoui

“I would have liked to see something here about the unequal relationship between the colonial power and its subjects,” says Nadia Nsayi, political scientist and public relations officer at the museum. Since her appointment in 2021, she has emerged as an important critic from within the ranks of the AfricaMuseum itself. She points to the word “acquisition” used in the description, a term that wrongly suggests neutrality and equality. She also points to the way in which the parties involved are described. Nsayi: “Whereas Belgians are mentioned by name in this story, Congolese people are presented as a functional, faceless mass – ‘rowers’ or ‘inhabitants of Bamanga’. Furthermore, even if the canoe was a donation, it was made in an unequal, colonial relationship, two years before Congo’s independence. But that is not mentioned either.”

Swamp

The entrance to the Wereldmuseum (world museum) in Amsterdam is in an equally white basement, where the ticket office and cloakroom lockers are located. A staircase leads up to the strikingly empty belly of the museum: the imposing central hall (lichthal), a darkened space which, with its high vaults, resembles a church. On its right flank, a man-sized projection screen, featuring portraits of a wide variety of people, fires personal, identity-related questions at visitors. These questions relate to the permanent exhibition Things that Matter. When do you feel at home? What do you want your clothing to say? What would you take a stand for?

Bisj pole carved from mangrove roots

Bisj pole carved from mangrove roots© Collection Wereldmuseum, Amsterdam

In the hall, six pillars are decorated with metres-high wood carvings of human figures. What do the signs here say about their origin? They are Bisj poles carved from mangrove roots, used by the Asmat (an ethnic group from the Indonesian province of Papua) in ceremonies to commemorate their dead. They depict deceased children and people killed by enemies. Enemies such as Dutch colonials? That is not mentioned. What is mentioned is that after the ceremony, the poles were thrown into the swamp to rot, thereby promoting the growth of food-producing sago palms. They are therefore also a symbol of fertility, part of the natural cycle of life.

The Wereldmuseum has sixty-three of these Bisj poles in its possession. The sign devotes a single sentence to their origin, “Many of these were collected between 1951 and 1958 by the collector Carel Groeneveld on behalf of the Tropenmuseum in Haarlem and the Wereldmuseum. Here too, neutral-sounding terminology is used, the Westerner is mentioned by name, the Asmat as a group. There is nothing about how the poles were acquired, the conditions under which they were shipped or the role of the museum itself in their “collection”. Nor is there mention of the fact that the Asmat’s territory was part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands until 1962.

Wayne Modest: In the current discussion about restitution, objects are sometimes so dominated by the European question about whether they were stolen that their beauty and meaning are relegated to the background

Professor Wayne Modest, content director of the Wereldmuseum since 2021, who acts as a guide here: “In the current discussion about restitution, objects are sometimes so dominated by the European question about whether they were stolen that their beauty and meaning are relegated to the background. A few of our partners in the country of origin told us to stop referring to their objects as colonial. That is why we put their significance first. But it is a matter of finding a balance. Soon there will be a touchscreen where visitors can request more information about the provenance of the objects”.

Looted art

Modest prefers not to use the term “looted art”. “We find it too simplistic and too limiting. We have 18,000 objects in our collection which we believe may have been looted. Calling them looted art means you fail to take into consideration the rest of the total of 450,000 pieces. That is why we prefer to talk about “object collection during colonisation”, following the example of the Restitutions Committee in the Netherlands. This allows us to discuss the significance of an object. Why people want it back. Whether something was purchased in a power relationship that leaves it unclear whether the seller really wanted to part with it, or whether he was so poor as a result of colonialism that he had to sell it.”

Colonial history is alive and well, considers Wayne Modest of the Wereldmuseum: “When you open your kitchen cupboard and see herbs, or a wooden chopping board or spoon made of tropical hardwood, that is how close colonial history is in our everyday lives!”

Colonial history is alive and well, considers Wayne Modest of the Wereldmuseum: “When you open your kitchen cupboard and see herbs, or a wooden chopping board or spoon made of tropical hardwood, that is how close colonial history is in our everyday lives!” © Mark Uyl

Since 8 May 2025, the Wereldmuseum Amsterdam has been hosting an exhibition devoted to questions like these surrounding provenance research. The exhibition, Unfinished Past: Return, Keep or…, will runs into early 2027. The museum has also dedicated a bay to current questions that put the ongoing discussion about looted art and the way in which pieces are handled into a broader perspective. The former Tropenmuseum (Tropical Museum) was renamed Wereldmuseum in 2023. Since 2014, its mission has been to “inspire global citizenship and thereby contribute to a better world”. The approach is broad, “Wereldmuseum explores what it means to be human, what our connection is to the world around us and how we relate to each other”.

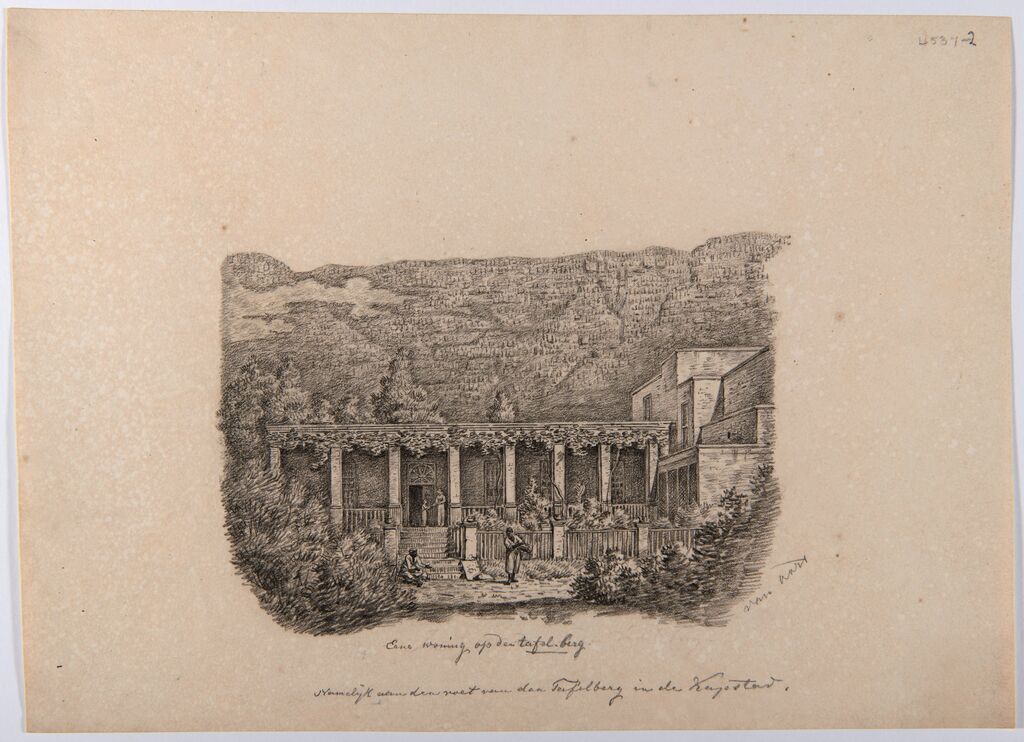

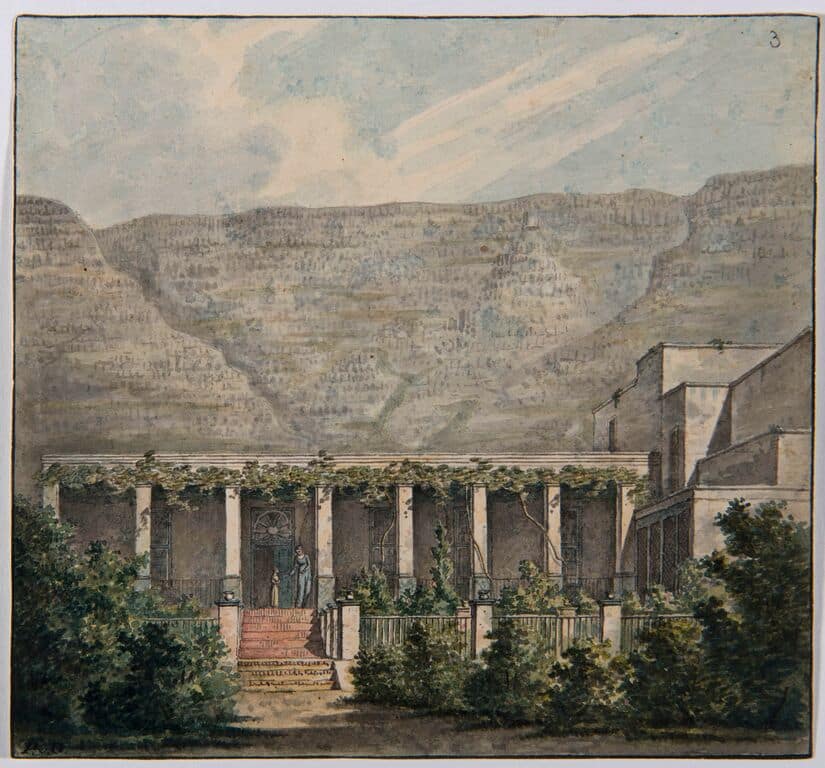

To illustrate this, Modest points to text panels that explain how the distinction between Western “art” in art museums and “craftsmanship” from the rest of the world in ethnographic museums has a stigmatising effect, between “higher” art from Western countries and “lower” art from other parts of the world. Modest: “We want to question those kinds of ideas, decolonise them, rewrite history. Photography, for example, whose invention may perhaps be claimed in London and Paris in 1839, also has a history in Suriname that began in 1845, but that is not always told because we are so busy navel-gazing. Or look at these two sketches, made by the Dutchman Pieter van Oort in South Africa (1826) of the same colonial mansion. The first black-and-white sketch shows two South Africans who were there at the time. In the second, coloured version, they have been omitted because they were not considered significant. We see this as symbolic of how people like that have been erased from colonial history. We are bringing them back into the picture.”

Sketches from 1826 of a colonial mansion in South Africa by the Dutchman Pieter van Oort. The black-and-white sketch shows two South Africans, but in the coloured version they have been omitted. “Symbolic of how these people have been erased from colonial history. We are putting them back into the picture.”

Sketches from 1826 of a colonial mansion in South Africa by the Dutchman Pieter van Oort. The black-and-white sketch shows two South Africans, but in the coloured version they have been omitted. “Symbolic of how these people have been erased from colonial history. We are putting them back into the picture.” © Collection Wereldmuseum, Amsterdam

For another example of critical commentary on the collection, Modest points to a large black-and-white contemporary painting entitled Tales of the Gold Mountain (2012), depicting a ravaged, polluted mining landscape with chains and a cross. “With this work, Indonesian artist Maryanto draws our attention to mining and what extraction means. Some of the first objects in our collection were mineral samples. When you look at the beautiful objects in our museum, you should realise that the metal was extracted from somewhere, and that this still has an impact on the planet today.”

“And here,” says Modest, pointing to another contemporary painting, entitled Reciting Rites in its Sites (2019), which shows a group of women and children in a circle, in a colourful garden with a gazebo, “here the Indonesian artist, Zico Albaiquni, is saying that even the botanical gardens that we enjoy visiting were a colonial project. All sorts of plants from all over the world were relocated to create them.” What Modest means is that colonial history is alive and well. “When you open your kitchen cupboard and see herbs, or a wooden chopping board or spoon made of tropical hardwood, that is how close colonial history is in our everyday lives! We want to draw attention to overlooked, rationalised issues like these.”

Tales of the Gold Mountain (2012) by Indonesian artist Maryanto shows a ravaged, polluted mining landscape with chains and a cross. The painting takes a critical, contemporary look at the Wereldmuseum's collection

Tales of the Gold Mountain (2012) by Indonesian artist Maryanto shows a ravaged, polluted mining landscape with chains and a cross. The painting takes a critical, contemporary look at the Wereldmuseum's collection © Rick Mandoeng

According to Nsayi, museums such as the AfricaMuseum are still not sufficiently aware of their own role, both then and now. She points to the Unparalleled Art room, where Tervuren’s masterpieces are on display. “There is hardly any mention of their provenance. Only function and aesthetic count. Look at the famous Luba mask plundered from the village of Luulu. It’s pure looted art. The text speaks in euphemistic terms of Central Africa instead of Congo and of ‘specific’ history instead of ‘colonial’ history. Africa had its own history before the arrival of the Europeans. What? The Europeans came to bring civilisation? African civilisation, with its kingdoms, is older than Belgium or the Netherlands!”

Nsayi points to the Nkisi Nkonde power statue, an “object” that had a living significance in Congo, “Stolen at the end of the nineteenth century in the Boma region, by the Belgian trader Alexander Delcommune, from King Ne Kuko. Nkisi statues protected the village. If you take them away, you rob a community of its soul. It’s like taking away our statues of the Virgin Mary. For a long time, this controversial looted art was kept in the museum basement. It was brought up when the museum reopened in 2018, was displayed in the temporary exhibition Rethinking Collections in 2024 and is now back here among the rest, as if there is no problem.”

Painful

Nsayi sees another objectionable aspect to the way cultural artefacts are “elevated” to art and contemporary artists are increasingly given a platform at exhibitions in post-colonial museums: “This is not an art museum! African artists are being used to aestheticize and tone down politically sensitive issues.” She points to the transparent curtain created by Congolese artist Aimé Mpane, which has been hung in front of controversial colonial statues in the museum building, and to the symbolically empty chair (Fauteuil Lumumba, 2014) commissioned by the museum and created by Congolese artist-designer Iviart Izamba as a commentary on the 1961 assassination – with Belgian assistance – of Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In Ruwatan Tanah Air Beta. Reciting Rites in its Sites (2019), Indonesian artist Zico Albaiquni is saying that even the botanical gardens that we enjoy visiting are a colonial project

In Ruwatan Tanah Air Beta. Reciting Rites in its Sites (2019), Indonesian artist Zico Albaiquni is saying that even the botanical gardens that we enjoy visiting are a colonial project © Collection Wereldmuseum, Amsterdam

Nsayi: “Imagine if former Prime Minister Alexander De Croo were murdered, cut into pieces and thrown into a hydrochloric acid bath without anyone ever being prosecuted for it. Would it be considered appropriate to dispense with it in a bit of art? This is all still relevant and painful and it’s not over yet! But the timeline stops in 1960, with the independence of Congo. The entire post-colonial period that we are in now, and of which colonial museums are a part, has been omitted.”

Nadia Nsayi : Many Africans do not recognise themselves at all in the caricatured way in which Africa is portrayed here. Imagine if there were a Dutch museum in an African country, filled with cows, windmills and clogs!

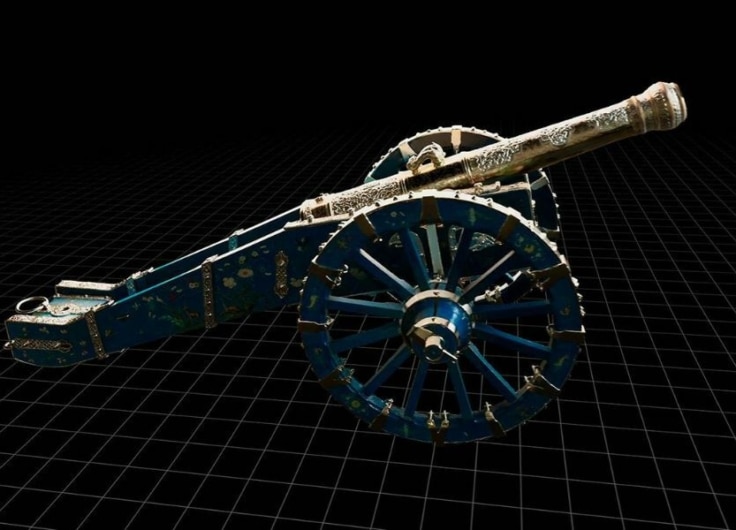

That is why Nsayi finds the name change of the museum in Tervuren problematic. “Why was this colonial museum renamed AfricaMuseum in 2018? It should be a museum about the colonial past and its impact on today. It is not a museum about Africa, but about the former Belgian colonial territories of Congo, Burundi and Rwanda. Established by King Leopold II as propaganda for his colonial plans. A showcase not only of looted artworks, but also a large collection of wood samples and a mineral cabinet, to show what could be obtained there. It was not only culture that was plundered, but nature too. The African Zoology department includes a million fish and six million insects. The museum also has 17,000 minerals, more than 80,000 wood samples and 200,000 rock samples. The collecting frenzy of museums like this is a Western phenomenon. Many Africans do not recognise themselves at all in the caricatured way in which Africa is portrayed here. Imagine if there were a Dutch museum in an African country, filled with cows, windmills and clogs!”

Facade

According to Nsayi, the core of the problem lies in the fact that the role of museums in research and restitution is presented as neutral, but it is not. Nsayi: “That facade must go. It is shameful to display these riches without also showing the colonial plundering and the current consequences, the human toll that is still being paid for them. The conflict with Rwanda in Eastern Congo, which is flaring up again now, is a direct result of this. But instead of a map showing armed conflicts that originated in the colonial era, what you see here is a pseudo-neutral scientific-geographical map showing minerals. Uranium, for example, was crucial in the Second World War. Its exploitation by Belgium enabled the United States to bomb Nagasaki. Without Congo, there would have been no Hiroshima. And here, diamonds. The fact that Antwerp is the diamond capital of the world is thanks to Congo. The approach here is supposedly neutral and scientific, whereas it should also be pedagogical and educational.”

One of the most grotesque “objects” in the proverbial china shop that is Tervuren is the stuffed elephant, placed on a raised platform, towering imposingly above the visitor. Nsayi: “The elephant was shot on commission especially for the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels.” There are many more large stuffed animals on display, as well. The silence that surrounds them is oppressive. There are zebras, buffalos, monkeys, and a complete family of okapis.

Nsayi: “The museum exhibits hunting trophies on the grounds that it is interesting for children, a fun outing for the whole family. But where do we listen to Africans? This violation of African nature and biodiversity is also hidden in the provenance trail that you first have to scan. Even though the museum itself played an active role in this.”

This elephant was shot on commission especially for the 1958 World's Fair in Brussels

This elephant was shot on commission especially for the 1958 World's Fair in Brussels © Africa Museum, Tervuren / Photo Jo Van de Vijver

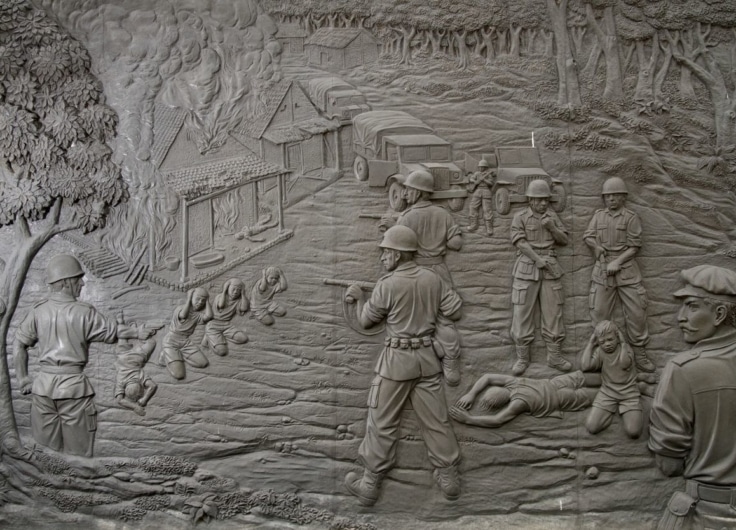

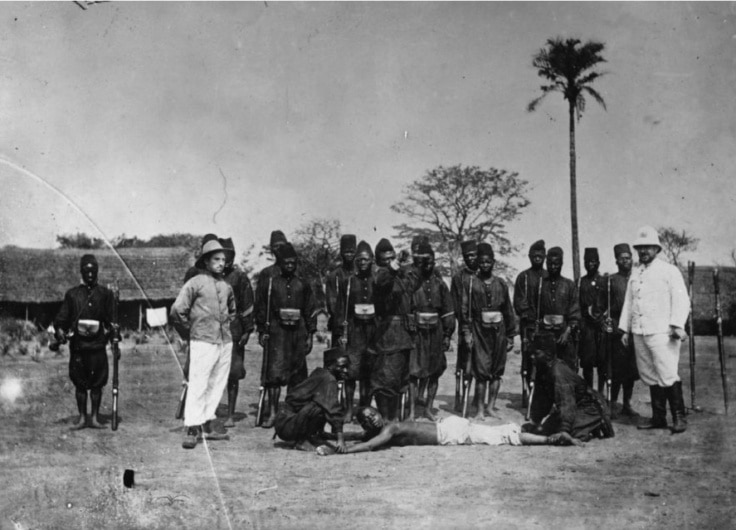

Nsayi believes that the violence of colonisation is still being glossed over too much, that you have to look too hard to find it. “Here,” she points to a collage of small photos on a digital screen that you can bring up at the touch of a button – the Belgian reign of terror in Congo. She points to a still photo, taken by an English missionary, of a Congolese man named Nsala, sitting on a veranda next to two unidentified lumps. Only when you look closer do you see that he is staring at the hand and foot of his little daughter Boali. Hacked off by Belgians during a massacre, because his village failed to meet the imposed rubber quota.

Display

The Amsterdam Wereldmuseum has consciously chosen to focus on other issues than the colonial violence to which people in former colonies were exposed.

Modest wants to move beyond that cliché. He considers inclusivity a given. In addition to providing insight into colonial history, he also wants to contribute to a new narrative. Modest: “I think we should stop displaying violence against certain people for the education of others. We do say, colonialism is racist, it cost many people’s lives and destroyed the planet. But we also want to focus on what was taken from the people: their humanity. By showing how those who were colonised, who had no hope and no reason for optimism, created hope through their faith, by fighting, loving, making music. We always see the enslaved as pitiful, struggling, we don’t see their joy, their creativity. We focus on their pain, we don’t see them as intellectuals and writers, politicians.”

Modest points to a portrait gallery of important thinkers from former colonial territories. “This is part of rewriting that narrative, by saying Anton de Kom, Aimé Césaire, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, Mohammad Hatta were important writers and thinkers, people who imagined what a different world could look like and who wanted to create it.”

Wayne Modest: We always see the enslaved as pitiful, struggling, we don't see their joy, their creativity. We focus on their pain, we don't see them as intellectuals and writers, politicians

Does the Wereldmuseum sweep its painful past under the carpet too easily? Modest: “The criticism of our museum is sometimes that we are not critical enough of our past. But I wouldn’t say that this museum sweeps things under the carpet. We live in a world that was created by colonialism. We must confront that, address it, but we also want to look at the ways in which people who were affected by colonialism created beautiful things and survived.”

Past?

Will the colonial past ever pass? Nsayi’s criticism, which she published in her column in the newspaper De Morgen, among other places, has led to parliamentary questions and discussions with the trade unions. Yet the internal debate – the collective discussion between the director and the museum staff that Nsayi has proposed – has still not taken place.

Nadia Nsayi: The objects on display here were often made before colonization, they can help visitors see that Congolese people did have a culture

Nsayi: “You should not make the colonial past, which is still present today, invisible, you should tell people about it critically. But you cannot open a museum to a diversity of critical voices and at the same time want to offer a pleasant, non-confrontational family outing. What is happening outside the museum in terms of debate, including King Philippe’s expression of regret concerning Belgian colonisation, is now an inspiration for young people of Congolese descent. Do something with that in the museum! The objects on display here were often made before colonisation, in pre-colonial times. They can help visitors see that Congolese people did have a culture, that they did have a civilisation.”

Nsayi concludes with an encounter from 2021, when she organised the exhibition 100xCongo at the MAS in Antwerp, featuring a hundred Congolese objects and the history of their provenance. “Then a young Congolese student intern came up to me and said, ‘Yaya Nadia’, which means something like ‘big sister’ in Lingala, ‘Oh my, we were intelligent!’ For me, that said it all.”

This is part one of a two-part series on looted art. You can read part one HERE.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.