‘De Randen’ by Angelo Tijssens: A Desperate Search for Affection

In pared-back prose, Angelo Tijssens tells the story of a gay man’s laborious search for a speck of love and affection.

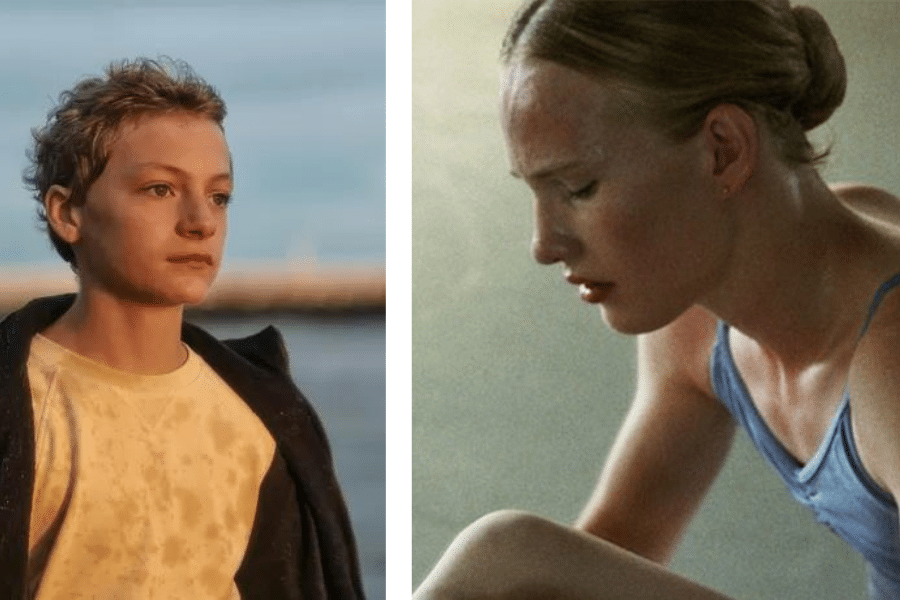

If you have seen the films Girl or Close by Lukas Dhont, or attended a theatre show by the Ontroerend Goed collective, you have already been acquainted with the storytelling talents of the Fleming Angelo Tijssens (b. 1986). To film (as a co-scriptwriter) and theatre, Tijssens has now added a new narrative form to his repertoire: the novel. Although his debut De Randen (The Edges) does hover between a novella and a novel, given its limited scope and focus on just one event and protagonist.

Angelo Tijssens

Angelo Tijssens© Borgerhoff & Lamberigts

As it is, the story of De Randen (The Edges) is pretty simple. When his mother dies, a man travels back to the place where he grew up in search of an old childhood sweetheart. Their renewed encounter brings back all sorts of memories, of his difficult childhood, with a tyrannical, alcoholic mother, and the gradual discovery of his sexuality.

It is clear there is not a lot of love in this man’s life, not then, and not now. His first encounter with people who are gay is with “the brothers” who live next door, until his mother discovers that they are not brothers at all, but “gays”, one of the many terms of abuse he hears. He understands that is something that is dirty, wrong, and the colourful beads he got from the men are thrown back over the hedge, although he does manage to save one from the clutches of his fuming mother. At school, meanwhile, the boy is labelled a social misfit.

Luck, or misfortune, well that’s something that happens on TV, in soap operas. Real life is an exercise in leaving behind

His first sexual experiences are just as loveless and bleak as the humiliations he endures at the hands of his mother. In the changing cubicles of the swimming pool, there are hand jobs and blowjobs, with a boy his age and with “the belly”, an older man. He later recognises him as the vendor in a snack bar, although he had already suspected as much from smelling “the belly”.

One time it seemed to go well, there seemed to be some love involved. But that also came to an end quickly because luck, or misfortune, well that’s something that happens on TV, in soap operas. Real life is an exercise in leaving behind. But still our narrator cycles through the pouring rain to this old love, looking for some affection, an ounce of warmth, a speck of love. Or maybe he is looking for what he left there with him.

Stills from the films 'Close' and 'Girl,' on which Angelo Tijssens collaborated as a co-scriptwriter.

Stills from the films 'Close' and 'Girl,' on which Angelo Tijssens collaborated as a co-scriptwriter.After their initial discomfort, the two men slowly warm up. The narrator opens up bit by bit, recounting stories he has never told before, because “not talking about scars has become second nature.” Now he lets his scars be caressed, even kissed, and it feels like a safe home.

But memories cloud the reunion. Our narrator has been with countless men, but for his childhood sweetheart it was only that once. After that first time, their breakup had been inevitable. But now there is doubt. The discomfort, the inability to really communicate, to express their feelings for one another, seeps out from the pages. What did they know then? What do they know now? How much have they changed? How terribly have they remained the same? How have their wanderings changed the course of their lives?

The discomfort, the inability to really communicate, to express their feelings for one another, seeps out from the pages

It is the style and language of this debut, much more than the story, that make it remarkable. Tijssens’s writing is economical, with short sentences and simple words. Often more is left out than said. Much is left to the reader’s imagination, who can shape their own story around what is given.

Tijssens mentions no names, no city, no time, everything has been stripped away until only the essential remains. We know nothing about outward appearances, except for the fact that the narrator once shaved off his long hair because he no longer wanted to be called “Miss” by unobservant ticket inspectors.

This is pared-back prose of a kind one rarely encounters in Dutch literature, prose that is reminiscent in places of Raymond Carver’s short stories. The show, don’t tell principle is implemented here to the extreme. There is no explanation, no context. As a result, it is also evocative and mysterious, compelling, and moving, sometimes poetic, often very raw.

As a debut, this short novel is promising, and at barely more than a hundred pages (there are no page numbers, which seems a bit pretentious, as if even those would distract) Tijssens perfectly maintains the tension in his bare prose. It will be interesting to see if he can do that with longer texts as well. And if not, we might have an excellent short story writer here. There is always room for more of these.

Excerpt of ‘De Randen’, as translated by Elisabeth Salverda

You taste blood and you smell wet lime. With half a bucket of lukewarm water and an old sponge earlier that day you had wet the edges of the wallpaper, because it makes it easier to detach from the wall with a palette knife, carefully, so you don’t accidentally chip the plaster. You will frequently smell wet lime, which you can taste on the back of your tongue. You will move at least nine more times. You will lose everything you currently own. Everything that seems valuable will vanish. Some things you will lose along the way, others you will flog intentionally to buy food or cigarettes, still others you will burn, give away, leave behind. You want to shout but you can’t because there is a hand around your throat. That hand is pressing your head against the wall. Black plastic tiles fall down, the most nocturnal frames of a comic strip crumbling before your eyes. You see the darkest squares, glue residue on the back, glue residue on the wall (and the time that slowly squeezed between them and moisture and soap residue). The people who lived in the house before you, an older couple who never had children, had thought it a good idea in times of prosperity to reject the old-fashioned tile and opt for the material of the future: plastic. What’s more, they also went for a soft blue wallpaper that you just now scratched off decades later. There’s blood on your lip, blood running down your chin, down her fingers. You can hear her voice echoing in the room where the tiles are falling. You have nothing, you have nothing on and you are nothing. She keeps repeating that last bit, loudly, you are nothing. It reverberates and the water is now sloshing over the rim of the bath. You don’t know what it is you did wrong, but it doesn’t matter now. You clasp your hands around her wrist and squeeze as hard as you can, but you seem to be tightening the grip around your own neck like a pair of pliers. You hear less and less but you see her mouth open and close. You can smell cigarettes, taste them too, as she spits in your face and loosens her grip, causing you to inhale hard, just before the back of your skull hits the rim of the bath. You try very hard not to cry as your mother storms out, through your bedroom, down the stairs, out the door, into the car, down the drive, until all is quiet. Until you begin to sob, gasping for breath, your throat full of lime, the fake tiles floating in the now-cold water, empty shells on brackish water. You cup your hands into a bowl and wash your face clean. You run your finger over your lip, feel the inside of your lip. You realize you’re not bleeding, and then you cry even more. You heat up some soup without turning on the lights. Your larynx hurts when you swallow but you eat without making a sound because you never know. You lie down, Beauty and the Beast are dancing on your bed sheets, but you pretend to be asleep and hope everything will be over soon.

Angelo Tijssens, De Randen. Borgerhoff & Lamberigts, 2022