White verandas, gently swaying palm trees, indigenous nannies playing with Dutch children in the grass, white men in spotless white uniforms and exotic landscapes. This is a prime example of the image many Dutch people have of the overseas territories during the colonial occupation. But where do these images come from?

These romanticised and somewhat distorted images are mainly inspired by the many amateur films that were made – particularly in the Dutch East Indies, but also in Suriname – and distributed from the late 1940s till the forced departure of many of the Dutch in 1957.

Those Dutch people who sought their fortune on the other side of the world were generally well-to-do, so many of them possessed a camera. The long journey to Indonesia was the ideal opportunity to get the camera out. The rolls of film were then sent back from the Dutch East Indies to the Netherlands with a letter, as a kind of ‘movie’. Once people arrived in the Dutch colony, they documented their stay there – the large villas, the (indigenous) servants, Dutch friends, Dutch things. Just as, these days, one only shows perfect pictures on social media, the tensions that existed between the Dutch and the locals did not appear in these home movies. In general, the move and their stay in the colony was a grand, exciting show. For many it was a huge culture shock as well.

Propaganda film

A number of propaganda films also supported the positive image of the colony, not only in the motherland but outside it, too. In the United States, especially, they could be useful, given the Americans’ great aversion to colonialism. It was important not to put too much stress on the image of the Dutch East Indies as a colony.

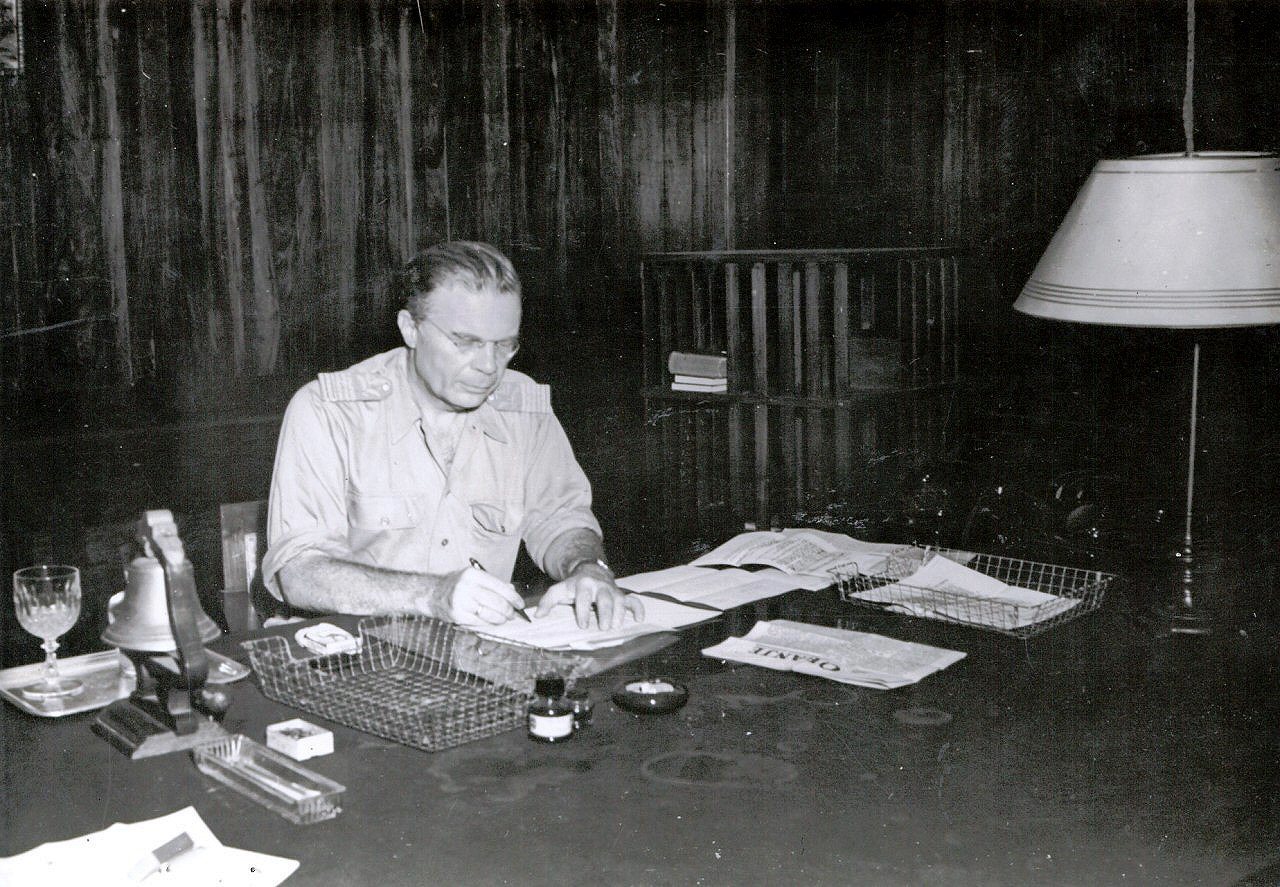

Huib van Mook in Batavia

Huib van Mook in BataviaIn 1938, the director of Economic Affairs in the Dutch East Indies, Huib van Mook, said, “The need for representative film material on the Dutch East Indies has been demonstrated so often recently that I consider myself discharged from the obligation to say much about it.” “At this juncture films are unequivocally part of a Government’s equipment”, he commented above a note that he speedily dispatched to The Hague. Van Mook had a plan. Twelve short documentary colour films – with sound – should be made about the Dutch East Indies. The result could be seen in 1941. The ten-minute-long High Stakes in the East was a documentary that completely ignored the acts of war there, except for the statement that the battle for the archipelago had been lost. Only the landscapes, the culture and the economy were dealt with in the documentary. What was stressed was the importance of recapturing the territory, to prevent all the valuable raw materials falling into the hands of the Japanese. Even though High Stakes in the East was a biased propaganda film, it was still rewarded with an Oscar nomination.

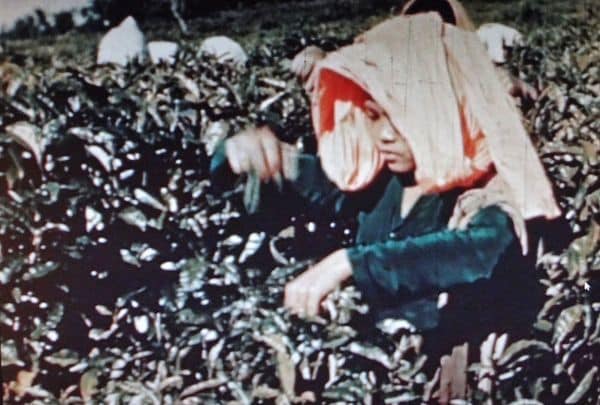

Stills from 'High Stakes in the East', 1941

Stills from 'High Stakes in the East', 1941Films from the decolonisation period

During the decolonisation period, which started after 1945, there were news reports about the situation in the Dutch East Indies, but these only touched on the number of dead and the political developments. What it was like for the ordinary soldier was barely mentioned, apart from a few amateur films. But these showed nothing of battles or skirmishes either. There was, for example, ‘What we did in our free time’ (Waar onze vrije uren bleven), by the army doctor Hans Nicolaï, in which soldiers with binoculars lie around on the beach ogling women in bikinis. Indonesië 1947-1950 by W. Dussel was more ‘correct’. Soldiers could be seen eating together and offering medical help.

The Netherlands managed to keep the misery of the war in the East Indies off the big screen, states Gerda Jansen Hendriks in her thesis, ‘An exemplary colony, a study of government films between 1912 and 1962’ (Een voorbeeldige kolonie, een studie naar overheidsfilms tussen 1912 en 1962, 2014). “In the propaganda films, which are used almost thoughtlessly again and again even today when the focus is on Indonesia, you will never see anything about the fierce guerrilla war that raged there. There are no iconic images, like those we know from the Vietnam war. We have to make do with films in which Indonesia is a country that cannot manage without the help of the Netherlands and the Dutch military.”

In terms of physical characteristics, the war of independence that raged in the Dutch East Indies in the 1940s was very similar to the Vietnam war. It was an uncoordinated guerrilla war in the tropics. Yet no images of the Indonesian independence struggle that might develop into a symbol of the war were kept. Such images of the Vietnam war were.

Still from 'Max Havelaar', a movie by Fons Rademakers, 1976

Still from 'Max Havelaar', a movie by Fons Rademakers, 1976© EYE Filmmuseum

Feature films

A number of very influential feature films and series have been made by Dutch directors about the overseas colonies. There are films with the Dutch East Indies in the leading role, including the 1976 film Max Havelaar. This film by Fons Rademakers, after the famous book of the same name by Multatuli, the pseudonym of Eduard Douwes Dekker, tells the turbulent story of a man who stands up to the corrupt government system. The book is considered to be one of the iconic works of Dutch-language literature and it even had (with a delay) a big influence on colonial policies. Havelaar, with his very critical view of the Dutch East Indies, was literally given a face in the film. It gave the Dutch population a penetrating view of the atrocities that took place in the Dutch East Indies.

However, Max Havelaar

was not the first critical film. Forty years earlier, Johan de Meester and Gerard Rutten’s Rubber had already shown day-to-day business in the Dutch East Indies. The film denounced the large-scale exploitation for the promotion of trade without any consideration for the welfare of the indigenous population. The film caused uproar in the Netherlands. The newspaper De Telegraaf

spoke of a ‘scandal film’.

There are also films in which the colonial administration in the Dutch East Indies provides more of a background. Hans Hylkema’s Oeroeg (1993), after the novella of the same name (1948) by Hella S. Haasse (1918-2011), gives a realistic view of the relationship between the Indonesians and Dutch in the 1940s. The film tells the story of the friendship between two boys. Johan is Dutch and Oeroeg is Indonesian. As children they were inseparable, but after the police actions Indonesia is no longer the safe colony it once was and Johan doubts whether he and Oeroeg can still be friends. The presence of the then-Queen Beatrix at the première was seen as highly symbolic. In 1993 this chapter of Dutch history was difficult to discuss.

The television serial De Stille kracht (The Hidden Force), after the eponymous novel by Louis Couperus (1863-1923), describes the uneasy relationship between Indonesians and Dutch people. The serial is set in Java, where an indigenous natural order prevailed alongside the Dutch administration. It was upheld by the so-called hidden forces or goenagoena, a term that refers to sorcery.

Still from 'Hoe duur was de suiker' (The Price of Sugar), a movie by Jean van de Velde, 2013

Still from 'Hoe duur was de suiker' (The Price of Sugar), a movie by Jean van de Velde, 2013© EYE Filmmuseum

Suriname was also the subject of films and series about the Dutch colonial past. In 2013, the film Hoe duur was de suiker? by Jean van de Velde, after the book The Price of Sugar by Cynthia McLeod (° 1936), was in the cinemas. The story describes what went on in Suriname in the period 1765-1779. It was the heyday of the sugar plantations, but it was also a period marked by the so-called Boni wars, in which the slaves revolted under the leadership of the half-Dutch, half-indigenous Boni. In the film, the plantation owners live in constant fear of attack by maroons (escaped slaves) led by Boni.

The best known film about Suriname, however, is Wan Pipel by the Surinamese-Dutch director Pim de la Parra. This 1976 film received a lukewarm reception in the Netherlands, but in Suriname ‘the first Surinamese film about Suriname’ was almost immediately seen as a classic. The portrait of Roy, a Creole economics student, who goes back to the town of his birth, deals with political and racial tensions. It was the first feature film to play in Suriname after the country obtained its independence and de la Parra was one of the few filmmakers who showed any interest in the country.

Besides this influential feature film, the documentary Faja Lobbi, which won a Golden Bear at the 1960 Berlin Film Festival, also stands out. Directed by Herman van der Horst, the documentary focuses mainly on the interior of Suriname, with its diverse population of Creoles, Hindustanis, Javanese, Chinese, Indians and Maroons.

Stereotypes must go

Fierce discussions about the Dutch colonial past and how it should be dealt with flare up regularly. A good example is the call that has resounded recently to rename streets, tunnels and schools that bear the names of controversial colonial ‘heroes’. In recent years the call for more awareness of the colonial past has grown considerably and films can contribute to that too.

In 2015, Floortje Smit suggested in the newspaper de Volkskrant that “Films should also dare to show the dark pages of the Dutch colonial past. And stubborn stereotypes in films should be identified as often as it takes for them to disappear.”