On a visit to the Flemish town of Oudenaarde, British journalist Derek Blyth discovers a battlefield that shaped European history, a cafe dedicated to cycle racing and a tapestry with a secret message.

As the train pulled into Oudenaarde station, I was hoping for a monument. Or a street name. Something to commemorate the Battle of Oudenaarde. One of the four great battles of the War of Spanish Succession, according to the book I was reading. The battles are celebrated in a series of Victory tapestries that hang in Blenheim Palace, near Oxford. The Duke of Marlborough, who led the Allied armies at Oudenaarde, commissioned them in Brussels to hang in his main hall. There really has to be a monument to the battle, I decided, as I stepped out of the station.

I nearly turned around. The station is an ugly concrete building in a sad neighbourhood. It replaced a beautiful 19th-century building with romantic Flemish turrets, one of the most beautiful stations in the country. Mysteriously, the old station is still standing, closer to the centre of town.

Oudenaarde's old railway station is a classified monument since 1994.

Oudenaarde's old railway station is a classified monument since 1994.© Wikipedia / Japplemedia

I passed several cafes clustered around the old station, all now closed down. There was a Stad Gent, a Stad Brussel and a Stad Brugge. Was this a warning? Take the train to Ghent, or to Bruges, go anywhere but don’t come to Oudenaarde, they seemed to say.

I set off down Stationsstraat in the direction of an impressive church tower. The street led to a traffic roundabout. Nothing to write about, I thought, until I noticed the name of the square. Tacambaroplein, the sign said, which sounded exotic. There was a war memorial in a small park off to one side. Voorbijganger Gedenk Maar Wees Niet Haatdragend – ‘As you pass by, pause to remember, but do not nurture hate,’ was the message.

It wasn’t the only war memorial on this square. There was a small monument to a solitary French hero and a rugged stone block with a metal plaque commemorating the liberation of Oudenaarde on 5 September 1944 by British troops and the local Resistance.

'The Grieving Woman' monument was erected in memory of the Battle of Tacambaro in Mexico.

'The Grieving Woman' monument was erected in memory of the Battle of Tacambaro in Mexico.© City of Oudenaarde

An even more impressive monument stood in the middle of the square. A woman holding a laurel wreath rests on a globe. I immediately thought, this must be dedicated to Marlborough. Only it wasn’t. An information panel told the story. The woman holding the laurel wreath is looking towards Mexico, it explained.

Mexico?

The statue is called The Grieving Woman. ‘From her lonely, elevated position she looks in the direction of Mexico, where Belgian volunteers went in 1864,’ the panel explains with a touch of poetic melancholy.

This strange episode began in 1859 when the young Austrian aristocrat Maximilian was invited to become Emperor of Mexico. He cheerfully took up the offer and sailed off to Mexico in 1864. And his Belgian wife, Charlotte, daughter of King Leopold I, went with him, accompanied by Belgian volunteers sent to protect her.

The volunteers had assembled in Oudenaarde and trained in the local barracks before setting off to Mexico. Soon after they arrived, a revolt broke out, and the inexperienced young men were sent to defend the remote town of Tacambaro. Facing an army of over 3,000 Mexican guerrillas, the 300 unlucky Belgians didn’t last long. Most were killed, including the son of the Belgian defence minister, in a disaster that might be called the Belgian Alamo.

Dozens of Belgian volunteers died during the Mexican adventure of Maximilian of Habsburg and Charlotte of Belgium, between 7 and 11 April 1865 in Tacambaro de Collados.

Dozens of Belgian volunteers died during the Mexican adventure of Maximilian of Habsburg and Charlotte of Belgium, between 7 and 11 April 1865 in Tacambaro de Collados.© Wikipedia

It seems Oudenaarde and Tacambaro are now the best of friends. In 2015, to mark the 150th anniversary of the battle, a delegation from Oudenaarde travelled to Tacambaro to discuss an agreement on tourism, education and culture. And a Mexican delegation was warmly welcomed in Oudenaarde. Wees niet haatdragend, you might say.

I was about to head off when I noticed another war memorial in a small enclosed park. The fifth, by my reckoning. The yellow sandstone monument was decorated with two splendid American eagles. It was in memory of soldiers from the United States who fought in another Battle of Oudenaarde. This one took place between 30 October and 11 November 1918. It was fought to secure a bridge across the river Scheldt near the village of Eine. More than 2,000 died in two weeks of fighting, tragically just a few days short of the Armistice.

American soldiers on the main square of Oudenaarde in 1918.

American soldiers on the main square of Oudenaarde in 1918.© City archives of Oudenaarde

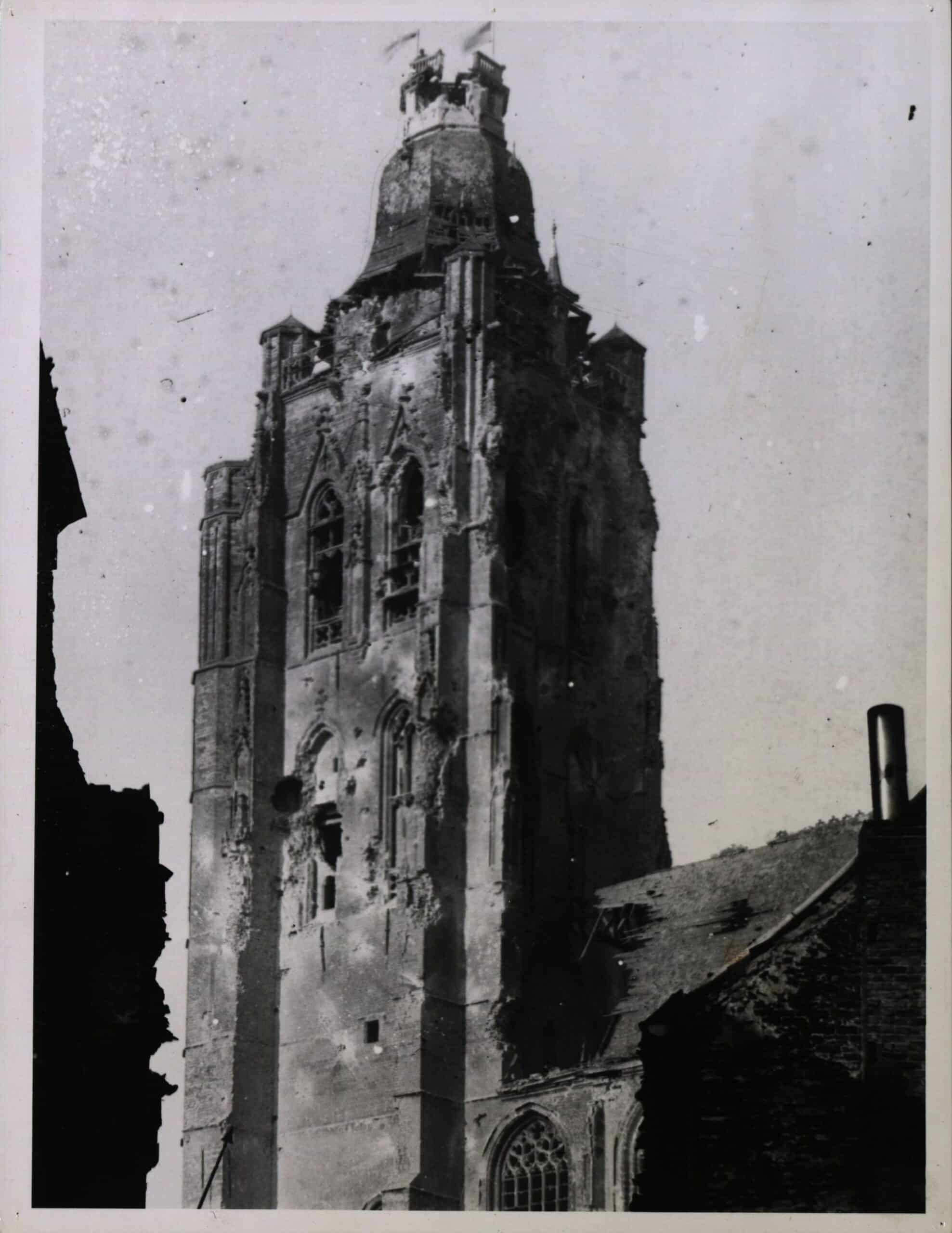

The St Walburga’s Church was heavily damaged during the First World War.

The St Walburga’s Church was heavily damaged during the First World War.© City archives of Oudenaarde

I was starting to understand the history of Oudenaarde. It was a story of one army after another marching through its streets and destroying its buildings. The town is dotted with information signs that show the destruction in 1914-18. I was beginning to wonder if anything old has survived.

The narrow shopping street Nederstraat is a lively and interesting route to the main square with interesting independent shops. I spotted an ice cream salon, a chocolate shop in an old corner building and a bookstore called Beatrijs (almost everything in Dutch, apart from a tiny selection of English and French novels).

It was market day and on the Markt square. The open space was filled with vans selling fish from Nieuwpoort, cheese from Passendale and biscuits from Diksmuide. You could also buy cheap socks, underwear and pink puffy jackets all the way from China.

It had started to rain, so I was looking for a cafe. An Oudenaarde local had advised me on the different cafes. ‘The Carillon is where the locals go,’ he explained, ‘While the cyclists hang out at the Peloton and the young people sit out on the terrace of the Adriaan Brouwer.’

I liked the look of the Carillon. It occupies two small gable houses built against the walls of the church. The carillon bells started to play a folk melody as I squeezed inside. It was 11 am and customers were already well into their first strong beer of the day. I studied the menu. It included local beers like Ename Blonde and Adriaan Brouwer Bruin, as well as a cheeky beer called Klootzakske (Asshole), described as ‘a blond beer with balls’.

Cafe The Carillon

Cafe The Carillon© City of Oudenaarde / R/DV/RS

I just had a coffee. It was 11 am for heavens’ sake. I am not a klootzakske. Soberly, I studied the interior, which sadly is not as old as it looks. It was reconstructed in 1921, after the German army had rampaged through Oudenaarde in 1914-18. The style a mix of old-fashioned half timbering and touches of modern Art Deco. The local artist Edgar Fobert decorated the interior with nostalgic scenes of pre-war Oudenaarde.

The flamboyant town hall of Oudenaarde

The flamboyant town hall of Oudenaarde© City of Oudenaarde

The market was packing up as I left the cafe, so I was finally able to admire the flamboyant town hall built in ornate Brabant Gothic style. It looks rather like the Broodhuis on the main square in Brussels. That is because they were both built by the same architect, Hendrik van Pede. He did Brussels first. Then Oudenaarde asked him to do something similar.

‘Every detail of this fantastic building is worth admiring,’ declared Victor Hugo. I followed his advice, and admired the delicate Gothic stonework, the curious statues and the vaulted arcade where schoolkids were sheltering from the rain.

Hanske De Krijger

Hanske De Krijger© City of Oudenaarde

Right at the top, the figure of the 16th-century city guard Hanske De Krijger (Hanske the Warrior) looks out across the city. According to a local legend, Hanske fell asleep at his post after drinking too much Oudenaarde beer. What a Klootzakske! Hanske couldn’t have picked a worse time, as Emperor Charles V was waiting outside the locked city gates. You might have thought that would be the end of poor Hanske. But the emperor turned out to have a sense of humour. As a gentle rebuke, he ordered the city to add a pair of spectacles to its coat of arms.

The story explained a logo I had seen on the tourist office website. At first, I thought it was a pair of cherries. Or possibly a bicycle. Now I knew the answer. When the city launched a new logo in 2021, they went for the spectacles.

Maybe Charles V decided to forgive Oudenaarde because of something that had happened a few years earlier. In 1521, he was staying in the city while his army besieged Tournai. The city officials in Oudenaarde put on a lavish feast in his honour. While he was staying here, the young Charles had a brief affair with a beautiful local woman called Johanna Van der Gheynst. It led to the birth of a daughter called Margaretha.

The emperor acknowledged her as his daughter and paid for her education. She went on to marry a Medici, followed by Ottavio Farnese, Count of Parma. In 1559, Philip II of Spain appointed Margaret (now ‘of Parma’) as Governor of the Low Countries.

Emperor Charles with his mistress Johanna Van der Geynst at the cradle of their daughter Margaret of Parma, painting by Théodore-Joseph Canneel, 1844, Museum of Fine Arts Ghent

Emperor Charles with his mistress Johanna Van der Geynst at the cradle of their daughter Margaret of Parma, painting by Théodore-Joseph Canneel, 1844, Museum of Fine Arts Ghent© Wikipedia

It was time to visit the town museum MOU. It is located inside the beautiful town hall and the more sober cloth hall next door. The Gothic interiors have been lovingly restored to create an exceptional museum. The highlight is a unique collection of Oudenaarde tapestries dramatically displayed in the vast cloth hall. Many of the examples are ‘verdure’ tapestries decorated with detailed forest scenes. Woven in wool, the works have faded over the years, but it is still possible to enjoy scenes representing the Trojan Wars, hunting parties and rural weddings.

The skilled weavers of Oudenaarde incorporated strange and sometimes amusing details into the tapestries. You might spot a mythical beast, or a mermaid or even a secret erotic message. The weavers often signed their final work with their personal symbol and then added Oudenaarde’s ancient logo in the margin. Look carefully and you will see a pair of spectacles.

Oudenaarde is world-famous for its tapestries.

Oudenaarde is world-famous for its tapestries.© City of Oudenaarde

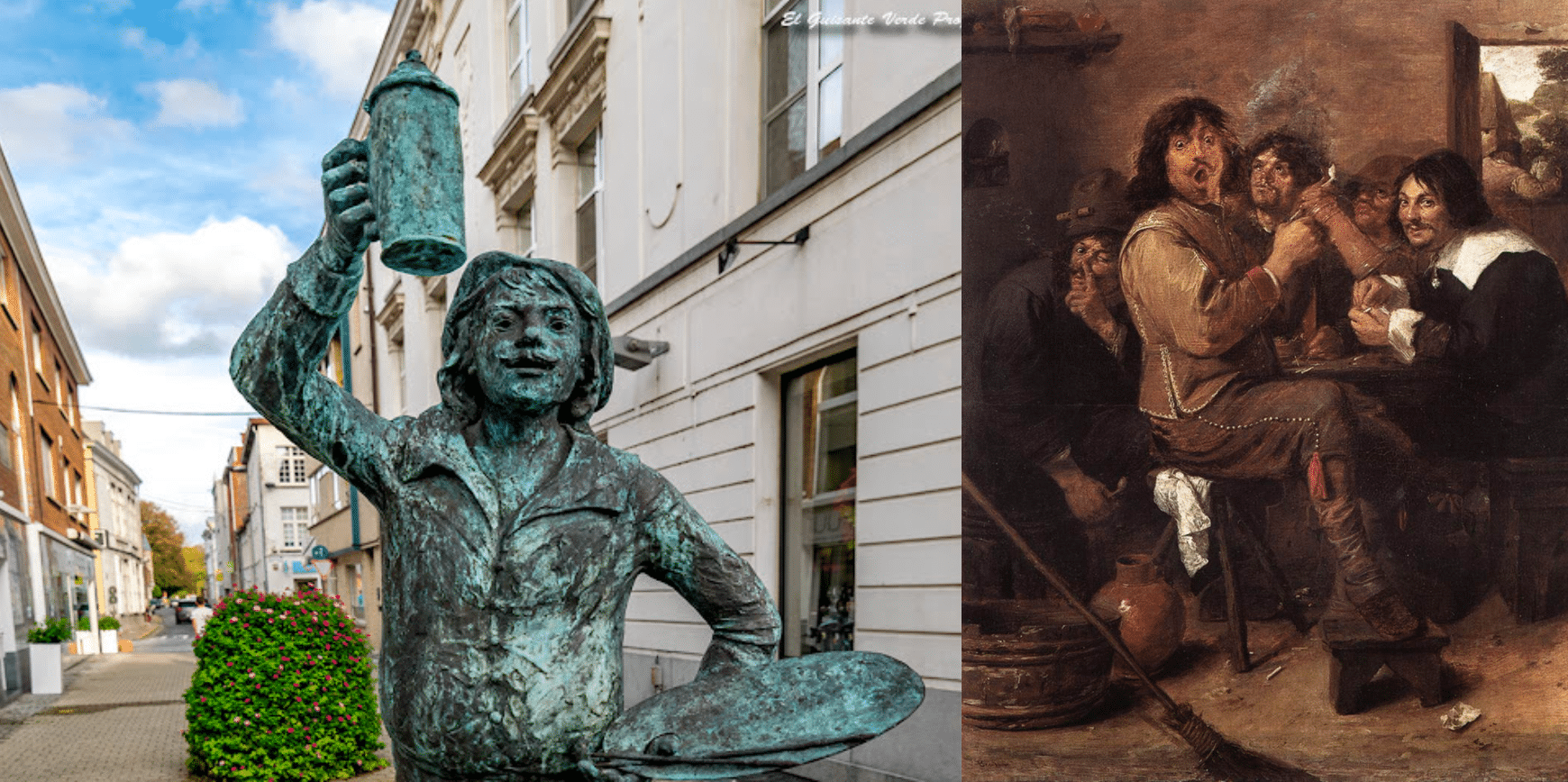

The museum screens a film in one of the old rooms on the ground floor. It is dedicated to the artist Adriaan Brouwer, who was born in Oudenaarde in 1605. Despite the name Brouwer (Brewer), Adriaan had nothing to do with beer. His father worked as a tapestry weaver, and moved to Gouda after the local industry collapsed. Adriaan went on to work as an artist in Amsterdam, then Haarlem and finally Antwerp. He only spent his early years in Oudenaarde, but the town has put up a statue in his honour behind the town hall. He is shown holding an artist’s palette in one hand, a beer in the other.

Statue of Adriaan Brouwer and one of his most famous paintings 'The Smokers'

Statue of Adriaan Brouwer and one of his most famous paintings 'The Smokers'© El Guisante Verde / © Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The MOU Museum has other rooms dedicated to a large silverware collection. In one room, a long table looks as if it is set for dinner with elegant examples of 18th-century silver cutlery, tureens and candlestick holders. Among the glinting treasures, I most enjoyed a quirky silver goblet decorated with a windmill that was used in aristocratic drinking games.

As you wander through the old rooms of the town hall, you come across relics of the city’s history: a fireplace filled with old iron cannonballs, a Gothic meeting hall named after Margaret of Parma, and an attic room where precious silverware is displayed. But, oddly, there is nothing about the history of Oudenaarde. I had been hoping for something about the 1708 battle, but the only relic was a painting of the battle hung without any explanation in a dark corner. It was by Alexander van Bredael, a local artist who also designed tapestries.

The Royal Fountain in front of the town hall was erected with the support of Louis XIV in 1675-77.

The Royal Fountain in front of the town hall was erected with the support of Louis XIV in 1675-77.© City of Oudenaarde

It would be interesting, for example, to know the story of the ornamental fountain that stands in the square outside the town hall. It dates from 1676 when the troops of Louis XIV were occupying the city. The French introduced a number of improvements to Oudenaarde including this splendid fountain decorated with four dolphins. They also brought drinking water to the city through a pipe that ran from a spring two kilometres away on the Edelaerberg.

The French occupied Oudenaarde on three different occasions. They improved the fortifications during periods of occupation and then destroyed the walls when they were besieging the city. During one of the quiet periods, Louis XIV commissioned a beautiful scale model of the city. It is now displayed in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lille, where it shows the brick houses with red-tiled roofs and back gardens in astonishing detail. It also reveals the mediaeval castle on the edge of the city after its walls were partly damaged by French artillery.

Scale model of Oudenaarde, anno 1748-1752

Scale model of Oudenaarde, anno 1748-1752© Musée des Beaux-Arts Lille

But then along came John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough. He had fought battles all over Europe, but he was particularly attracted to the hilly region around Oudenaarde. ‘Nowhere else in Europe is better suited to the conduct of war,’ he argued. He praised the meadows, rolling hills and small villages. It sounded idyllic, as if he was planning a cycling holiday.

I set off from the museum to explore the old town. I soon reached a landscaped promenade that runs next to the river Scheldt. The hydraulic bridge across the river had just been raised to let a huge barge pass through. It gave me time to kill, so I studied a sign mapping a new cycle superhighway that ran along the river. In one direction, Kortrijk, 33 km. In the other, Ghent, 30km. Oudenaarde in the middle.

Church of our Beloved Lady in Pamele along the river Scheldt

Church of our Beloved Lady in Pamele along the river Scheldt© EFlor

Once the barge had passed, I crossed to the other side. This was the independent town of Pamele until it was swallowed up by Oudenaarde in 1543. It has a beautiful stone church next to the river built in the austere Gothic style that developed along the river Scheldt. The door was locked, but a sign outside told an interesting story. Margaret, the illegitimate daughter of Charles V, was baptised here. A century later, the French used the church as storehouse. And in 1918 the building was badly damaged as troops fought for control of the bridge.

Some attractive old buildings have survived on this side of the river, included a beautiful red renaissance building that was once the Maagdendale Abbey. It is now occupied by an art academy that hosts edgy art exhibitions, along with the local archives and an indoor shooting range.

Brewery Liefmans

Brewery Liefmans© Liefmans

Walking in the opposite direction, I came to a brick building where Liefmans brews its cherry beers. It all started in 1750 when Jacobus Liefmans started brewing on the banks of the river Scheldt. But the brand really took off after the company took on Rosa Merckx as master brewer. She is credited with the beer’s subtle taste as well as the stylish silk paper wrapping.

Back across the river, I wandered around trying to find a way into the Begijnhof. Eventually, I came to a red gatehouse that led into a walled cluster of neat white houses overlooking a formal garden. Like every Begijnhof, this hidden spot close to the river feels like a town within a town, a quiet mediaeval sanctuary where single women lived independent lives.

I explored other neighbourhoods where the architecture was a mix of different styles and periods. Even the main church Sint-Walburgakerk was a baffling clash of different styles. I originally thought it was all down to war. But the city officials added to the destruction in the 1960s. They even demolished a cluster of old houses next to the church to build a four-lane highway. Some of the damage has been repaired, but there is still a large car park right in front of the church.

The public library of Oudenaarde is housed in a 18th century building.

The public library of Oudenaarde is housed in a 18th century building.© Wikimedia Commons

Despite everything, Oudenaarde still has some exceptional buildings, including a puzzling Neoclassical building on Markt. Built in the 1780s, it was originally divided in two, with a meat market on the ground floor, and a drawing academy on the first floor. It is now the public library, which explains the motto at the top. It reads, vLEESHUIS, a clever play on vleeshuis, a meat market, and leeshuis, a house for books.

I also discovered a city park called Liedtspark that originally belonged to a 19th-century castle. Landscaped in English garden style, the park has kept its meandering paths, romantic bridges and picturesque ponds. It is enclosed on one side by a stretch of the old city wall that has somehow survived every invading army.

The Centre Tour of Flanders is where you can relive the Tour of Flanders cycle race, also known as Flanders' Finest.

The Centre Tour of Flanders is where you can relive the Tour of Flanders cycle race, also known as Flanders' Finest.© City of Oudenaarde

My short walk in Oudenaarde ended at Cafe Peloton on the Markt. The cafe is attached to the Centrum De Ronde van Vlaanderen (Centre Tour of Flanders), an impressive exhibition centre dedicated to the Tour of Flanders cycle race. I have always struggled to understand cycle racing. And I am not the only one. Among the books on sale in the shop, I noticed one with the title, Hoe wordt je een wielerfan? How do you become a cycle fan?

Would you even want to be one? You stand in the rain, is my experience. Nothing happens for an hour. Then someone shouts, ‘Here they come.’ And then, before you know it, the peloton has flown past. And that’s it for another year.

Together with the Koppenberg and the Oude Kwaremont, the Paterberg is one of the toughest slopes in the cycling race the Tour of Flanders.

Together with the Koppenberg and the Oude Kwaremont, the Paterberg is one of the toughest slopes in the cycling race the Tour of Flanders.© EFlor

I know it’s more than that. The Flemish cycle races are a test of endurance. The low hills around Oudenaarde are gruelling cycling challenges, almost like battles. There’s the Oude Kwaremont, the Koppenberg and more than a dozen other summits where the crowds gather. They might not look impressive compared to the Alps, but these slopes are punishing on a bike. Some of the cobbled roads are protected monuments. Even if they weren’t, no local official would ever dare to put down asphalt.

The low hills around Oudenaarde

The low hills around Oudenaarde© City of Oudenaarde

I sat down in Cafe Peloton to soak up the atmosphere. The interior has historic racing bikes hanging from the walls, along with suspended lights made from bicycle wheels and cycle jerseys displayed in glass cases like precious religious relics. Outside, the terrace at the back has a row of mini exercise bikes, some cycle-based games and a playground with little bikes.

The centre welcomes cyclists from all over the world who have decided to spend a few days in the sacred hills around Oudenaarde. There is secure bike parking, showers and a shop where you can pick up souvenirs. You can also rent a racing bike for the day with breakdown assistance, a shower and a beer as part of the package. Cyclists who spend a night in Oudenaarde often stay nearby at the modern Leopold Hotel, where the bar and restaurant are decorated with giant photos of cycle heroes.

The big race happens every year on a Sunday in early spring (3 April in 2022). The Ronde van Vlaanderen, or Vlaanderens Mooiste (Flanders’ Finest), brings some of the world’s great cyclists to the Flemish Ardennes. Starting off in Antwerp this year, the cyclists follow a gruelling 250km route that takes in 17 steep hills, five villages and several stretches of bumpy cobbled roads. The riders end the race in Oudenaarde where they cross the chalked finishing line under the tower of the Sint-Walburgakerk.

The Tour of Flanders in Oudenaarde

The Tour of Flanders in Oudenaarde© Ronny De Coster

All right, I thought. I am in the world capital of cycling, so I am going to have to get on a bike. I decided to plan a route that would take me to the site of the 1708 battle. I found a detailed account of the battle on the specialised website, Belgium, Battlefield of Europe. Created by a small team of military experts, the site provides precise details of the battle. The French army was the stronger force, with 95,000 troops. The Allied army, made up of troops from Britain, the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany, numbered just 80,000 men.

The Duke of Marlborough at the Battle of Oudenaarde in 1708.

The Duke of Marlborough at the Battle of Oudenaarde in 1708.© Wikipedia

It looked as if I could easily get to the battlefield by cycling down the Scheldt to cycle point 89, then head north to the village of Eine. From here, I would be following Marlborough’s troops after they crossed the Scheldt on the morning of 11 July.

I headed down the Schelde, then swung left to the village of Eine. Then it was a slow climb up to the village of Mullem. I was now riding through fields where Marlborough’s troops had marched as they headed towards the French artillery lined up along the ridge.

Mullem is a pretty village where all the cottages are painted yellow ochre. It could almost be Denmark. Heading up the steep hill behind the village, I passed an elegant castle with a mysterious brick belvedere. It might have been built for stargazing. But no one seems to know. A neat avenue of trees led from here to a low summit with sweeping views across the rolling fields. Here was where the two armies clashed.

Mullem

Mullem© Peggy's Pastime Blog

The cycle route follows the ridge, past a restored windmill. Then the road becomes cobbled for a 1.5km stretch that is a protected monument. Not because of what happened in 1708, but because the Tour of Flanders sometimes passes this way.

Bump. Bump. Bump. I cycled along the road, trying to imagine Marlborough’s troops marching through the fields to my left. I stopped to admire the view. In the distance, across a rolling landscape that reminded me of a Bruegel painting, I could see the tower of Oudenaarde’s church. I decided to head back downhill. It was time for a local beer on the Markt square. Maybe an Adriaan Brouwer. Or I might dare to ask for a Klootzakske.

This article was realised with the support of the Flemish Government.