#23 – Geert Groote and the Modern Devotion’s Fight Against the Excesses of the Church

In the late Middle Ages, innovative ideas entered the Roman Catholic Church thanks to a Dutch priest. Geert Groote is known as the father of the Modern Devotion, a religious movement, that can be considered one of the forerunners of the Reformation. His spiritual legacy had followers across Europe for many centuries.

At the beginning of the 15th century, towns in the Oversticht, the region which mostly makes up today’s modern province of Overijssel but at the time was controlled by the prince-bishop of Utrecht, reached their medieval zenith largely because of their involvement and affiliation with the Hanseatic League. Strategically positioned along the IJssel river, which connected the Zuiderzee to the Rhine, towns such as Deventer, Kampen and Zwolle were able to take part in the sprawling trade network of northern German cities which dominated trade over the North and Baltic seas.

Map of the Low Countries with the main trading towns on the IJssel in the Oversticht: Kampen, Zwolle and Deventer. Made by David Cenzer.

Map of the Low Countries with the main trading towns on the IJssel in the Oversticht: Kampen, Zwolle and Deventer. Made by David Cenzer.But although the trading connections brought increased power and wealth to the region, it was also here that a new spiritual movement known as Modern Devotion was founded by a man called Geert Groote, who rejected the materialism and excesses of the Church and its clergy and called for sober, inward, religious reflection. His followers, known as the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, would spread throughout the Low Countries and parts of Germany creating schools, copying and producing books, and increasing literacy levels throughout society.

Engraving of Geert Groote

Engraving of Geert GrooteGeert Groote was born in Deventer, one of these big trade towns on the IJssel, in 1340. He was the only son of a wealthy patrician cloth merchant. His father, Werner, was in the ruling elite of the town and served as the city’s treasurer on two occasions during Groote’s childhood.

It is reasonable to assume that the young Geert was being prepared to follow in his father’s footsteps. But, life in the 14th century was unforgiving at the best of times and in 1350, not one, but both of Groote’s parents died of the Black Plague. Now suddenly orphaned, he was put in the care of an uncle and studied at the famous Latin School in Deventer, before being sent at the age of fifteen to Paris for further study at the Sorbonne, funded by the wealth he had inherited after the death of his parents.

Groote graduated from the Sorbonne at eighteen years of age, and although the full details of the next few years of his life are largely unknown, it is believed that he continued living and working in Paris for the next few years, studying medicine, theology, astrology and canon law. On two separate occasions during his time in France, he acted as the representative of the town of Deventer to the antipope in Avignon and he eventually earned positions working as a Church administrator in Aachen in 1368 and then in Utrecht in 1372.

Groote studied medicine, theology, astrology and canon law

So, Groote grew up privileged, with financial means, extremely well educated, and through his early work life would have learned how to wheel and deal with the elite of the Church hierarchy, knowing whose hands to shake and which wheels to grease to manoeuvre his way up the ladder. Up until this point, his life was much like that of many others who operated in that upper realm of the social spectrum.

But sometime around 1372-1374 Groote experienced a life-changing epiphany. According to one story, Groote suffered from a severe illness which brought him to the edge of death. A priest was brought in to give him the last rights, but upon seeing books in his house which he claimed contained “black magic” refused to perform the ritual. Upon this, Groote took his books to the main square of Deventer, known as de Brink, had them publicly burned and thereafter made a full and unexpected recovery from his illness. Following this he decided to give up his former lavish lifestyle and start afresh on a new spiritual path.

Medallion with the effigy of Geert Grote at the Latin School in Deventer

Medallion with the effigy of Geert Grote at the Latin School in Deventer© Wikipedia

Whatever the veracity of this story may be, it is clear that something majorly altered his outlook on life. In 1374 he had his family home in the city of Deventer transformed into the Meester Geertshuis, a kind of hospice or shelter wherein poor women could serve God. There they would engage in devotional prayer, care for the sick, support themselves through manual labour like sewing or weaving, and were free to leave if they wished. He then went and spent a large part of the next five years living in a Carthusian monastery called Monnikhuizen, near Arnhem. Whilst there he never took vows, but he must have spent hours undergoing intense personal reflection, analysing his life up until then and where he could change his ways.

Furthermore, Groote also clearly thought about the material body by which people connected to God, the Church, considering its current state and whether it truly served the purpose it was meant to. At some stage, he came to find himself filled with criticisms towards it. According to van Engen’s Sisters and Brothers of the Common Life, Groote found his old lifestyle “more unclean than he had words for”. Instead, he resolved that the way to live a truly Christian life was to imitate Jesus Christ and his initial followers, and wrote down resolutions about how he would do so.

Geert Groote determined that the Church was being tainted by the self-interest of the priests, bishops and clergy

He saw all kinds of corruption in the Catholic Church if viewed through this more austere lens, and he now turned against it. He determined that the Church was being tainted by the self-interest of the priests, bishops and clergy who were taking positions purely to gain personal wealth, property and prestige. He targeted pluralism, which had become common practice. This is where people would attain multiple benefits, and salaried positions within the Church, but the actual work of which they could farm out to others for a lower amount.

Basically, rich people were getting richer for nothing by manipulating the mechanisms of Church administration. He also found it incongruous how many monks lived lives of luxury inside monasteries whilst simultaneously begging for money on the streets. Groote was vehemently against the taking of concubines by priests, another practice not difficult to find being engaged in. He believed that what was important was one’s own personal connection to God and he wanted to get away from what he saw as the worldly and corrupting distractions within the Church to focus on the true meaning of piety and Christianity.

In 1379 he was encouraged to go visit the prince-bishop of Utrecht and, perhaps surprisingly, the prince-bishop showed an interest in the things that Groote was saying. He was allowed to become a deacon, a kind of travelling lay preacher who would go from town to town in the Nedersticht and the Oversticht giving the word to crowds of people. He spoke in Deventer, Zwolle, Utrecht, Amersfoort, and Delft, and began setting up houses and schools across the region. He worked with a man named Florentius Radewyn in creating a house in Deventer where teams of young priests could copy books. His most famous work is a Book of Hours, a prayer book written in the Dutch language, not Latin, which made it possible for common people to work on their own personal spiritual development. In so doing he attracted both followers and detractors.

Book of Hours by Geert Groote, ca. 1460-70

Book of Hours by Geert Groote, ca. 1460-70© Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht

You might very well imagine that a bunch of priests, living deluxe lifestyles with their mistresses, did not exactly like the message that Groote was spreading. In 1383, enough pressure was put on the prince-bishop of Utrecht by opponents of Groote that he was compelled to cease allowing unordained deacons, like Groote, to preach. Within twelve months of that ban, Groote’s remarkable life came to an end, when he succumbed to the same fate that his parents had, the plague.

Devotio Moderna

Although Groote himself died, his message did not. His ideas resonated with many people. It is important to remember that the Catholic Church at this point was in a moment of crisis, there were two men running around claiming to be Pope and the abuses which he pointed out must have been glaringly obvious to many.

By writing in the vernacular he brought the message of Christ’s life and the ideals by which one should live to have a virtuous life to a much larger audience. Some historians have suggested that Groote can be viewed as a forerunner to Martin Luther and the Reformation, whilst others point out that this is probably going too far. It does seem that Groote was more interested in attacking the morality of the clergy and trying to bring about change within the established Church, rather than going after the theological foundations which underpinned the Church itself, as Luther would do.

By writing in the vernacular he brought the message of Christ’s life and the ideals by which one should live to have a virtuous life to a much larger audience

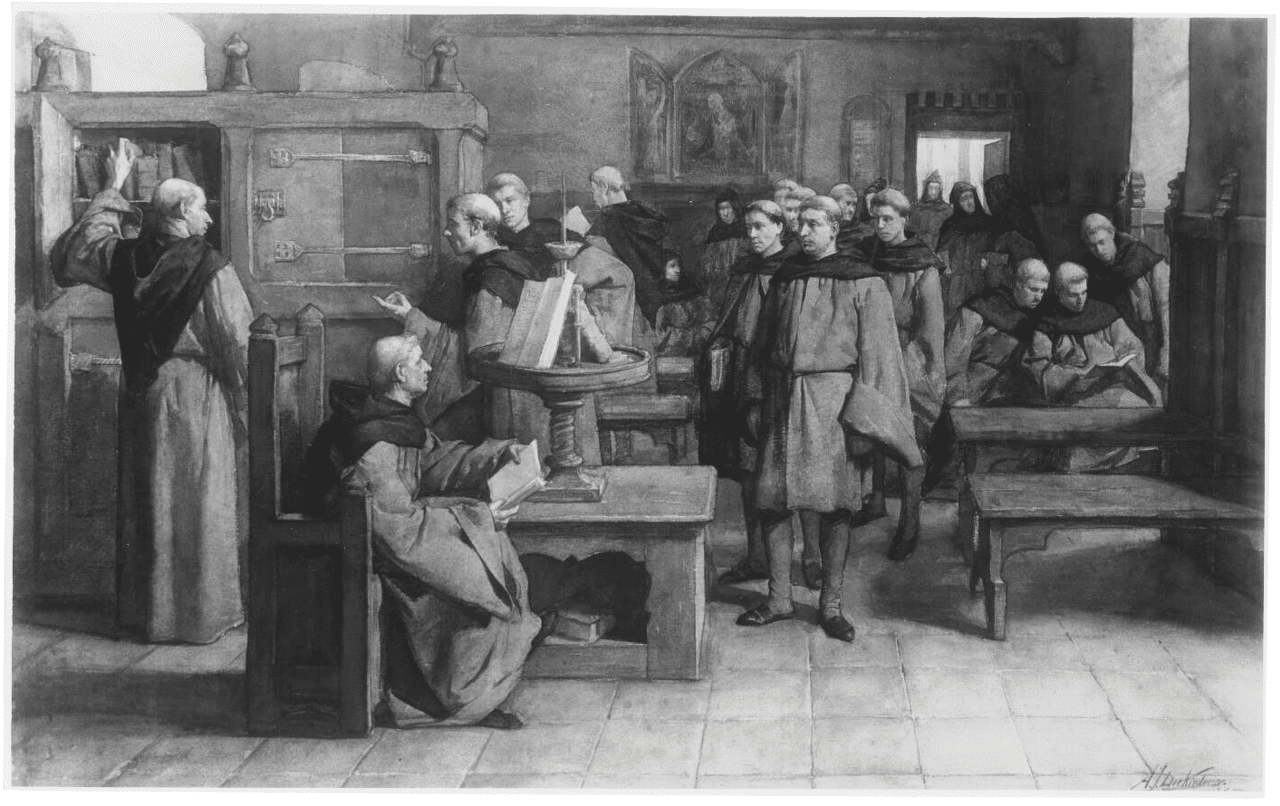

Whatever the case may be, the movement he created became known as Devotio Moderna, or Modern Devotion. There were three separate branches of “the Devout” as they became known. Women who Groote had housed in his former family home in Deventer laid the foundations for the Sisters of the Common Life, and an analogous group made up of men became known as the Brethren of the Common Life. The third branch, set up by his colleague Florentius Radewyn, was a more formally organised monastery at Windesheim, close to the town of Zwolle.

The Brethren and Sisters of the Common Life

were communities of mostly lay people who took no vows, yet dedicated themselves to a lifestyle of doing charitable work, taking care of the sick, reading and studying the Bible and other religious texts, copying books and setting up schools to educate the masses. Although the first of the houses set up by the Brethren of the Common Life were based in Deventer and Zwolle, from there they spread throughout the Low Countries and Germany. Houses were opened, amongst others, in Amersfoort in 1395, Munster in 1401, Delft in 1403, den Bosch in 1424, Doesburg in 1426, Groningen in 1430, Gouda in 1445 and Utrecht in 1474. Unlike monks and nuns who lived cloistered lives, locked behind large walls and separated from the societies around them, members of the Brethren of the Common Life were encouraged to take an active role in the wider community.

Romanticised depiction of Geert Groote with his followers (Modern Devotion), later Brethren of the Common Life. Watercolour by Anthony Derkinderen, 1885.

Romanticised depiction of Geert Groote with his followers (Modern Devotion), later Brethren of the Common Life. Watercolour by Anthony Derkinderen, 1885.© Wikipedia

The efforts of the Brethren of the Common Life in regard to education are famous to this day. Many members worked in prestigious educational institutions and the schools in which they were influential were renowned for the quality of education and attracted the best scholars of the day. In addition to this, they also enabled poorer children and children from rural areas to attend the public schools in towns. The houses which they created also acted as a kind of dormitory for these children and the Brothers would pay for the school fees of those who could not afford it, as well as offer them tutoring and spiritual guidance. The schools run by the Brethren of the Common Life were also simply huge. It’s estimated that up to a quarter of the residents of Deventer and Zwolle were being taught by the Brothers. In other towns, the Brethren also set up boarding schools which were renowned for their strict discipline.

Many famous pupils attended schools run by the Brethren of the Common Life. These include Desiderius Erasmus, although admittedly he did not have many nice things to say about them, writing once in a letter that he found his stay at the school in ‘s Hertogenbosch a waste of time because he knew more than his teachers did. Martin Luther himself attended a school run by the Brethren at Magdeburg and Thomas of Kempen was taught at the Latin School in Deventer which was led by one of the Brothers. Kempen’s book, The Imitation of Christ, lays out the principles of the Modern Devotion movement and provides spiritual instruction. It would become one of the most read Christian devotional books of all time, still thought to be the second most read book in Christianity to this day, behind only the Bible.

In their essay Why Did The Netherlands Develop So Early, Ter Weel, Webbink and Akçomak claim that the most important legacy of the Brethren of the Common Life

was their role in building what they called “human capital” in the Low Countries. Through the copying of books, and eventually printing after the invention of the press, by creating educational institutions and promoting learning for all, the Brethren of the Common Life helped raise the level of literacy in the Low Countries to a much higher level than other contemporary and nearby societies.

In the Netherlands in 1500 the number of book editions created per capita was 25% higher than in Germany, 3 times higher than in France, around 8 times higher than in Spain and Portugal, and 10 times higher than in England. In addition to this, the presence of a Brethren of the Common Life house also played a strong role in city growth in the period between 1400-1560; those cities with a Brethren house grew on average 35% more than those without. This suggests that the strong presence of the Brethren of the Common Life also helped fuel economic growth within the Low Countries in this time period.

This article is part of a podcast on the lucrative involvement and trade relations of the towns in the Oversticht with the Hanseatic League in the Middle Ages.