Hendrik Tratsaert: ‘Flanders’ Greatest Enemies Are Self-Censure and Self-Hate’

Flemish self-awareness – for some it’s the highest good, for others a tainted anachronism. Hendrik Tratsaert has taken a position somewhere in the courageous centre of that continuum. The new director of the non-profit Ons Erfdeel, which publishes, among other things, the periodical de lage landen and the website the low countries, regrets that the debate has degenerated into a polarisation between the populist right and the tendentious left, as he said in an interview with the Christian weekly Tertio, which we have translated for you.

For one month they doubled up, the departing director Luc Devoldere, on the threshold of retirement, and his successor Hendrik Tratsaert, who took up the torch on 1 January. Tratsaert is certainly not without credentials. A native of Ostend, he earned his spurs as the driving force behind numerous cultural projects.

Now he has taken over Ons Erfdeel, an institution with a robust reputation. The periodical de lage landen (formerly Ons Erfdeel) has reported on language, literature, art, history and society in Flanders and the Netherlands since 1957. Today it does it in three languages, both online and in print (Dutch, French and English).

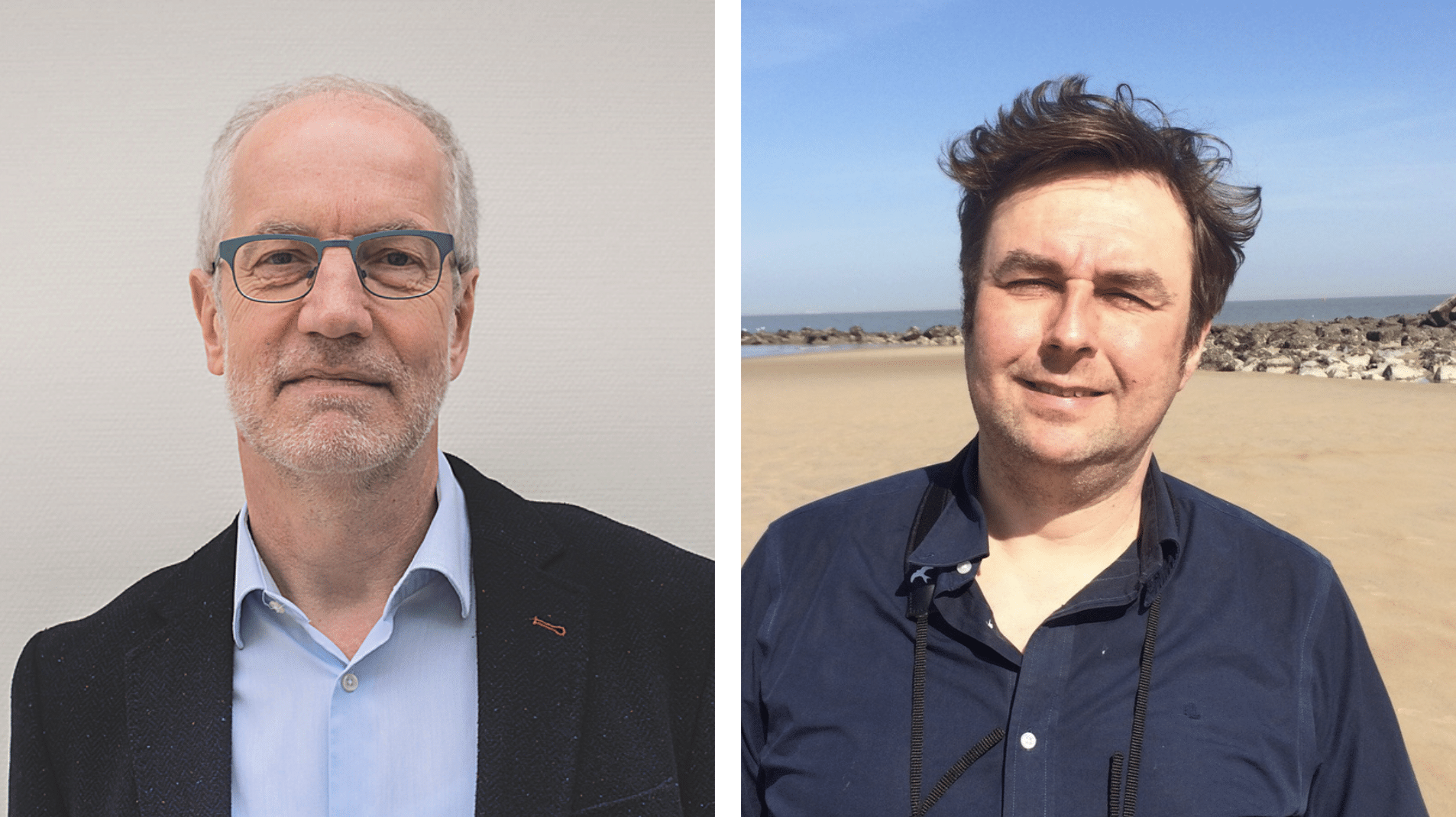

Luc Devoldere (editor-in-chief from 2002 until 2020) and his successor, Hendrik Tratsaert

Luc Devoldere (editor-in-chief from 2002 until 2020) and his successor, Hendrik TratsaertThe period when Ons Erfdeel came into being was steeped in the urge for emancipation. How did the organisation position itself in this?

Hendrik Tratsaert: ‘After WW2 Flanders mirrored itself, in terms of identity, on the Netherlands. It was a necessity. On the one hand, because the presence of dialect was prominent here and, on the other, because intellectuals used French to a large extent. The better Dutch language books were written in the Netherlands. Within the Belgian state structure and the social reality, Flemish emancipatory aspirations flourished. Eventually that led to the establishment of the language border and constitutional reform, which gave Flanders more self-determination.

Jozef Deleu, founder and editor-in-chief of Ons Erfdeel vzw until 2002

Jozef Deleu, founder and editor-in-chief of Ons Erfdeel vzw until 2002© ikwashier.be

The founder of Ons Erfdeel, Jozef Deleu – a real giant – worked tirelessly in the interests of the language, a sound education system, the emancipation of our art forms and the affirmation of Flemish identity. He was an unceasing advocate for recognition, institutionalisation and the safeguarding thereof in government spending.’

So, the approach was political from the outset?

‘Cultural politics. Never partisan but influencing policy with firm recommendations. Over the last twenty years, our political voice has been less loud. Many battles have evolved in the right direction, like the cultural budget, for example, the emancipation of the language and education, and the cooperation with the Netherlands. Our debating culture in the early days, with polemical essays and pamphlets that forced the discussion into the media, gradually shifted towards reflection. The delusions of the day in the generic and social media have increased the need for anchors with deliberation and nuance. That is why we now give more space to long, reflective pieces.

Our presence in the public debate is still non-partisan and based on a long-term view of culture. As far as I’m concerned, an independent Flanders is not essential. And having the right party card doesn’t make you a good Fleming. I prefer to interpret Flemish identity more freely, as inclusive, open to the world and cross-ideological. Both right-wing liberals and left-wing socialists can feel Flemish and affirm their identity as Flemings.

The current identity debate has turned inward too much and become a permanent, self-satisfied reflection of ourselves, whereas a self-confident Fleming looks beyond the borders and enters into dialogue with the world. Those who are small become bigger by relating to others, not by making themselves small(er). Hence the importance of our communications in French and English, which enable non-Dutch-speakers to perceive us as broad-minded Flemings. The debate has degenerated due to polarisation between the populist right and a tendentious left. My activist friend, the author Jeroen Olyslaegers, said in the newspaper De Morgen that he is shifting towards the centre because there are no longer many people there. He confirms what I have felt for a long time, the need for a broad platform, because the extremes are driving us apart.’

‘Flanders and the Netherlands do not form a community of destiny, but a community of interests’, your predecessor once said in Tertio (31/05/17). Is that your opinion too?

‘There is a distinction between the Flemish and Dutch identities. Flemish culture occurs within the linguistic border with some spillover into French and Zeelandic Flanders. In addition to that, there is a large area where Dutch is spoken. To a certain extent these once formed a single identity. After all, when the Scheldt was closed in 1587, a significant part of the Flemish intelligentsia fled to the Netherlands. In Dutch language forums, in books, at universities, in embassies and consulates, we affirm the fact that we speak Dutch.

Hendrik Tratsaert: 'Flemings are the sum of many identities due to foreign domination and alliances.'

Hendrik Tratsaert: 'Flemings are the sum of many identities due to foreign domination and alliances.'For the Dutch, their identity is unambiguous because they are a nation-state. Flemings straddle their linguistic relationship with the Netherlands and their Belgian nationality. And that’s not unambiguous either, with bilinguals in Brussels, and Walloons who until two centuries ago didn’t all speak French but Walloon, which is half-German or a sort of Limburgish. We are the sum of many identities due to foreign domination and alliances. Flemings have to learn to be content with their past and its consequences, their Latin-Romance nature – laid-back and Burgundian – and their Germanic disposition – hardworking and structured. We are not unambiguous, not just one or the other in the same soul.’

Are the Flemings and Dutch growing closer to each other or are they drifting apart?

‘Our relationship has evolved. In the decade from 1970-80, Flemings looked up to the Dutch because they were more secure in their language and pursued a more effective (cultural) policy. In the meantime, due to self-governance, a strong education system and emancipation from dialect, Flanders has become more self-confident. As a result, Flemings no longer see their northern neighbours as an identity to be imitated. These days the Netherlands and Flanders are good neighbours, but I would say that it is more of a marriage of convenience than a passionate love. We are very different. Even our art. You cannot compare the baroque Rubens and the sober Rembrandt – although they were contemporaries – and that is still evident in today’s art production.

Obviously, because of the shared language there is plenty of room for cooperation. Compare it to the Anglo-Saxon world, the historic link between the UK and the US is a question not of roots but of language. That applies equally to la Francophonie. Dutch would benefit from that type of geostrategic zone in which language and culture are promoted, too.’

Is promotion in other language groups important if you want to safeguard a culture? Or do you focus mainly on self-respect and pride?

‘We’ve gone beyond the stage of self-doubt. Now the mantra is more like ‘Show, don’t tell’. Not activism, but a sort of self-evidence – entering into dialogue from a position of love and critical reflection about our own culture. Culture is a major area in which there is a constant exchange. There is too little media coverage from across the language border. Globalisation as a postmodern statement is wearing off everywhere in favour of nationalism and the affirmation of one’s own identity. I regret this evolution, because I believe in dialogue and links within a margin of negotiation or healthy verbal conflict.

Abroad, people are very happy with our French and English reporting. You can only appreciate others by immersing yourself in their culture, but then there must be material available. That’s why we engage in culture export, a mercantile-sounding expression for immaterial goods.

We also maintain good contacts with the many small cells of ‘Dutch language and culture’ at universities all over the world, from St Petersburg to Buenos Aires. Because of this cooperation and appreciation, we are seen as self-confident Flemings extending a hand.’

To what extent is Flemish still synonymous with Roman Catholic?

‘Flanders has been steeped in Catholic culture for centuries and it has permeated our art and our cultural heritage. You cannot understand a painting by Rogier van der Weyden without a knowledge of the Bible. But faith has evolved a lot in our country, and you can’t get around the separation of Church and state. De lage landen reflects that evolution. I regard the close association of Flemish and Catholic by some Flemish nationalists as rather hypocritical. They have few links with the Church and faith but want to emphasise Christian identity mainly for the benefit of a purely anti-Islam discourse.

Roman Catholicism still influences our attitudes and the way we think

In my opinion, the Enlightenment was the most important driver of cultural development. It brought independence of thought and pluralism. If we abandon the values of the Enlightenment – and above all the search for truth – we end up with shallow populism and fake news. However, my belief in the Enlightenment does not detract from my respect for religion. I was brought up as a believer and am familiar with the rituals and Bible stories. The Dutch writer Connie Palmen once said, “the Bible is superior fiction”. And anticlerical writers like Jan Wolkers and Hugo Claus claimed to have learned their language from the Bible and its fantastic metaphors. I endorse that. Roman Catholicism still influences our attitudes and the way we think. My predecessor calls that “post-Catholic”. Catholicism is an historic reference for our culture, but in contrast to that there is now critical reflection and free-thinking.’

Culture is subject to two main pressures these days. The sector has been badly hit by the corona measures and in education the number of teaching hours is in danger of being cut back. What is going on?

‘In the past, all art came from the bourgeoisie and then returned to it. Art has always been the backdrop of power. Jan van Eyck could not have painted the Ghent Altarpiece if it had not been commissioned by the wealthy Judocus Vijdt. The state has taken over that role now and has followed the societal trend of thinking in terms of ever faster and more efficient profit. Culture does not deliver an immediate economic advantage. In a materialistic society that enshrines education in a particular economic system, culture and art come under pressure. Oscar Wilde said, “Art is quite useless”. Culture is not economically useful, but it is worthwhile. For many people, art provides meaning and a transcendental form of comfort, just as faith does for others.

Moreover, art and culture are an expression of our identity. We must dare to affirm that importance in our policies. In Flanders, the concentration of theatres, concert halls and cinemas is one of the highest in the world. All the global stars and alternative performers come here. We have the best choreographs and top painters. We should cherish that, cherish both our old and our contemporary art production.’

How do you rate the current cultural policy? Is it restrictive, as some people say?

‘It is true that over the last 10 years – under three different parties, by the way – there were budget cuts in culture. Even the Flemish Minister-President Jan Jambon began by making cuts, though in the meantime that mistake has been put right, thanks to campaigns by the sector and the support of opinion-makers in the broader social field. During corona, the government created a safety net for the cultural sector, so you can’t claim there were cutbacks. Actually, I think that the sector lacks a certain introspection and self-criticism. Flanders’ greatest enemies are self-censure and self-hate. Self-censure is opposed to critical thinking that dares to go against the grain. Persistent polarisation disrupts the debate, because an opinion is always stuck in one of two camps, the populist right or the tendentious left.

At Ons Erfdeel we want to circumvent that with critical nuance and distance. Self-hatred refers to how Flanders regards itself. It needs to think much more freely and settle once and for all with issues from the past that keep coming back, but which no longer concern the younger generation, like collaboration, for example. Until the state reforms of the 1960s, Flemish identity got too little recognition. But we’ve gone a stage further now, haven’t we? As far as I am concerned, self-confident Flemings have nothing to do with the frustrated Flemings that are still struggling with the past.’

Are you in favour of a Flemish canon?

‘There’s nothing wrong with a canon, especially if it covers the past to, let’s say, WW2. It’s more difficult with living arts because a selection may be presumptive. Only time can judge whether something is significant beyond the borders of the nation – because that is an important criterion. I think that some parts of the intelligentsia have reacted too fast. A balanced jury was put together under the leadership of the prominent and irreproachable historian Emmanuel Gerard, and the whole spectrum is represented equally. Everything depends on the purpose the canon is meant to serve. If it’s a bible to be learned by heart uncritically, then I pass. If it’s a proposal of works to be used in education or to show the highlights of Flemish culture beyond our borders, then I’m all in favour of the project.

Because of populist quibbling, we can no longer look at the canon open-mindedly

The Netherlands has an interesting canon concept with fifty windows on culture, and France has included a selection of culture in the education curriculum. Flemish curricula already include a lot of things that will be in the canon too. Obviously, the selection must be diverse and critical, with regard to sensitive subjects such as colonisation and collaboration for example. Interpretation is everything. I have the feeling that the debate is becoming unnecessarily ideological. Because of populist quibbling, we can no longer look at the canon open-mindedly. There has been hardly any discussion about the composition of the jury, which actually means well done.’

Another concern, young people’s diminishing language skills. Does that disturb you?

‘The risks are twofold, the anglicisation of everyday language, especially in the Netherlands, and colloquial Flemish. I am in favour of dialect, but I abhor verkavelingsnederlands. It irritates me enormously that, in their lust for popularity, celebrities and actors infect Dutch in the media with cheap colloquialisms. There’s nothing wrong with a regional accent; what’s at issue is style, grammar and vocabulary. In the public forum you speak Standard Dutch. Language is a form of hygiene, self-care and communication.’

How does a niche periodical like de lage landen, or its English language counterpart the low countries, survive these days?

‘All periodicals are under attack, but since we digitised we reach three times as many readers. It’s much easier now to respond to current affairs and make links. We use three different media to communicate: magazines, online channels and publications. The proportions have to be right, of course. Online channels require speed, a periodical can take a little more time with things.

Only the quality fora will continue to exist on paper, I think. The greater the care taken, in terms of content and form, the greater the chances of survival. Long essays, for which you take your time and whereby you also enjoy the design and the tactility, will remain. Cheap promotional editions will also survive, but everything in between will disappear in the long run.’

What would you like to achieve as the new director?

‘The periodical needs to become even richer and more urgent, both in form and content. I want to maximise its added value vis-à-vis the websites. I want to engage in the debate a bit more, too – online, in the press, and live in Flanders and the Netherlands. The Dutch presence needs to be stronger as well. But I’m not going to touch the sense of intrinsic quality and the relevance of the mission which my predecessors watched over so carefully.’

This interview first appeared in the Christmas edition of the Christian weekly Tertio.