James Ensor, Painter of Both the Exalted and the Vulgar

On 19 November it will be 70 years since James Ensor died in a hospital in Ostend. Writer Koen Peeters, who published his novel A Room in Ostend this year, brings an ode to this ‘realist, pleinairist, painter of light and masks’, who would go and salute his own statue at the casino.

Over the last three years I would go to Ostend for two days every month, accompanied by my good friend Koen Broucke. What we enjoyed doing most was to drop into people’s homes, and look out of the highest window in the building. Ostend from an attic room.

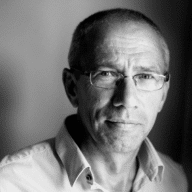

James Ensor at work

James Ensor at work© Fonds Ensor

City scenes from above, just like the young Ensor who enjoyed painting from his attic studio. Up there, there is more sky than houses, the closeness of the sea is palpable. Up there, all is ephemeral clouds, mists and light. You also see how small people are, parading around and taking their daily walk along the dyke. Every time I think of James Ensor.

And even in the many auction houses and flea markets of Ostend I recognise the remnants of bourgeois interiors, dark and perishable, like the hybrid compositions of Ensor’s still life paintings.

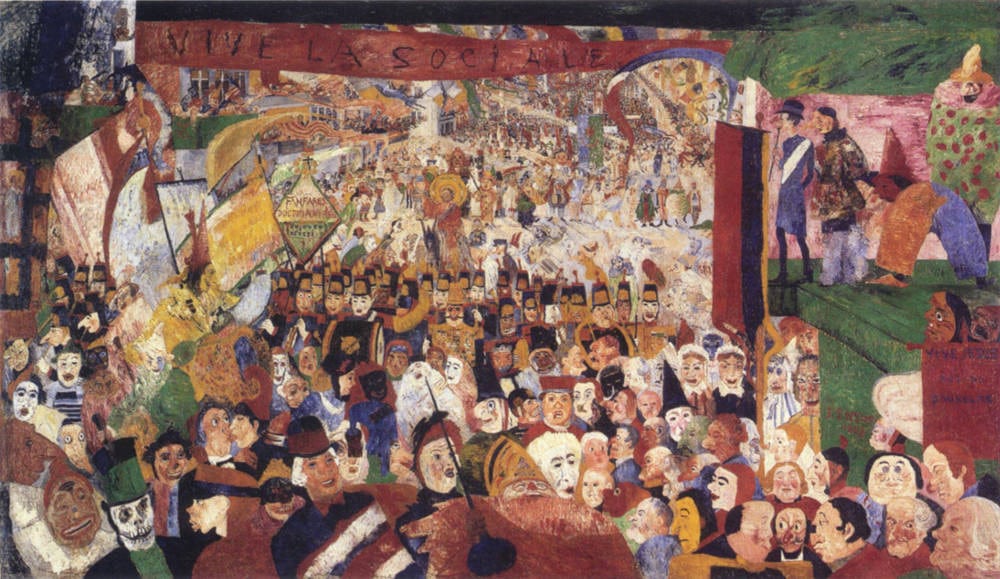

A few times we accompanied Xavier Tricot, Ostend’s Ensor-expert. His life’s work is the James Ensor Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings. As long as new and fake works keep appearing, that work won’t be finished. We walked with Tricot through the Langestraat, Van Iseghemlaan, the Adolf Buylstraat and the Vlaanderenstraat, and he pointed to houses. Or rather, the places where Ensor had lived and worked, because all but one of those houses have disappeared. On the corner of the Vlaanderenstraat and the Van Iseghemlaan he pointed up. ‘There, in that apartment building with the tinted windows, he painted his Christ’s Entry Into Brussels.’

Nothing is safe in Ostend.

Ostend! How everything evaporates and changes. It is just like Ensor saw Ostend transforming.

James Ensor, Christ's Entry Into Brusselsl, 1888

James Ensor, Christ's Entry Into Brusselsl, 1888© J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

As a young boy James saw how the city canals were filled in and the city walls were demolished. Ostend went from being a garrison town, to a petit Bruxelles. The ramparts became a mundane promenade with an increasing number of new and newer hotels, and a casino. It was here that Leopold II invested his stolen money from the Congo. People took the waters. People went roller-skating, did archery, pigeon shooting, played tennis and took up equestrian sports. Whenever the young Ensor wanted to escape all of this, he took his brushes and palette knife, and set up his easel in the dunes. He painted the sky and the sea. He became more and more occupied with colours. The atmosphere, the mist on the horizon, grey-green and grey-blue.

He studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Art in Brussels. On winter evenings he visited the left-liberal Ernest Rousseau and his wife Mariette, with whom shy Ensor was secretly in love. He came into contact with other intellectuals, lovers of art, freemasons and nobility. However, he only achieved measured results at the Royal Academy. People called him the Grim Reaper because he dressed in black and was tall and slender.

Mariette Rousseau and James Ensor, ca. 1888

Mariette Rousseau and James Ensor, ca. 1888photo by Ernest Rousseau junior

Ensor retreated to Ostend to help his mother in her shop. He wrapped up porcelain and faience, and seashells for collections. His mother thought he was slow, but he worked hard in his studio – for his whole life: 850 paintings, 100 etchings and thousands of drawings. Realist, pleinairist, painter of light and masks. Voilà, his career.

Rejection made him irritable, but at the same time, he seemed to relish incidents, refusals to exhibit his work. All the while, he painted mass scenes. Piles of people, crowds, social unrest. ‘He was well acquainted with the exalted, but liked to wallow in primitivism and vulgarity too’, says Xavier Tricot.

Ensor locks himself into this grumpy and mocking artist-character. He draws grotesque fellows, bare bottoms, defecation. His irony is grubby and generous. He chooses the everyman and laughs with the Beau Monde and the tourists who buy seashells in his mother’s shop.

Ensor paints against the church, the king and the establishment, but at the same time he is bourgeois with a sense of justice

He meets his long-term girlfriend Augusta Bogaerts, whom his family forbid him to marry. They meet each other in hotels in Brussels. Another girlfriend calls him a terrible lover. Sexual impotence. Psychoanalysts talk of castration, transvestism and anxieties. He paints beheadings, eunuchs, snobs. He especially mocks himself, in the same way Christ is mocked. Did he too know that he would still be proved right?

Ensor paints against the church, the king and the establishment, but at the same time he is bourgeois with a sense of justice. Over the years, and with the success that finally, and liberally arrives, he becomes complacent and greedy. He enjoys having his ego caressed. He makes replicas when people ask him to. He wasn’t even particularly socially minded. He had sympathy for little people like workers, fishermen, washerwomen, but only on a theoretical level. It was by no means political.

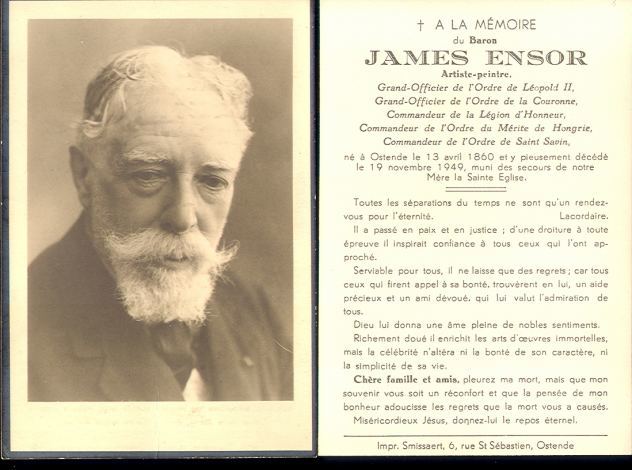

In 1929 King Albert I makes him a lord. He paints even more self-portraits, floral arrangements, still lifes, increasingly harmless and rosy. Still lifes with herring, crab, bottles, shrimp and rye. Savoy cabbage, peaches and cherries. Vases and flowers and a dead duck or cockerel. Admirers come to visit him and he grumpily shows them his blue salon with its piano and harmonium.

Meanwhile, we wander along the dyke with Xavier Tricot. ‘Ensor’s grandmother even had a dressed up monkey with which she went out’, explains Tricot. Ensor also practiced this type of gaudy walking, and went to greet his own statue at the casino. In his later life he had turned into a round-bellied bourgeois gentleman with a white beard and a dirty black suit. He died on November 19th, 1949, in a hospital in Ostend.

Tomb of James Ensor; Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-ter-Duinenkerk, Ostend

Tomb of James Ensor; Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-ter-Duinenkerk, Ostend‘There are no longer any privately owned Ensor paintings in Ostend’, says Tricot. Only stories and the ghost of Ensor, busy destroying itself. More than ten years ago the letters BARON were stolen from his grave, an anarchistic stunt carried out by De Stoete Ostendenoare (The Fearless Ostenders). The letters have since been stuck back on. Soon a spacious, residential tower block with 26 floors will be erected on the Oosteroever. The name: Ensor Tower. Ensor was avant-garde and at the same time mercantile and opportunistic because money had to be made. After all, everyone wants money.

We – everyone, just like artists – are delicate people searching for recognition. But what sublime, delightful and sometimes hilarious art James Ensor has left behind for us.

Many thanks to Xavier Tricot. In May 2020 a new Ensor Space will be opened next to the Ensor House on Vlaanderenstraat. The first exhibition Tricot will be organising there is Ostend and James Ensor.