Laura Vroomen’s Choice: P.F. Thomése and Andreas Burnier

Every month, a translator of Dutch into English gives literary tips by answering two questions: which translated book by a Flemish or Dutch author should everyone read? And, which book absolutely deserves an English translation? To get publishers excited, an excerpt has already been translated. This time you will read the choice of Laura Vroomen, who translated work by the likes of Saskia Noort and Ernest van der Kwast.

I’ve long admired the way short stories and novellas can evoke intricate worlds in relatively few pages, conveying a depth that belies their modest size. So I’d like to take this opportunity to celebrate two shorter works of prose.

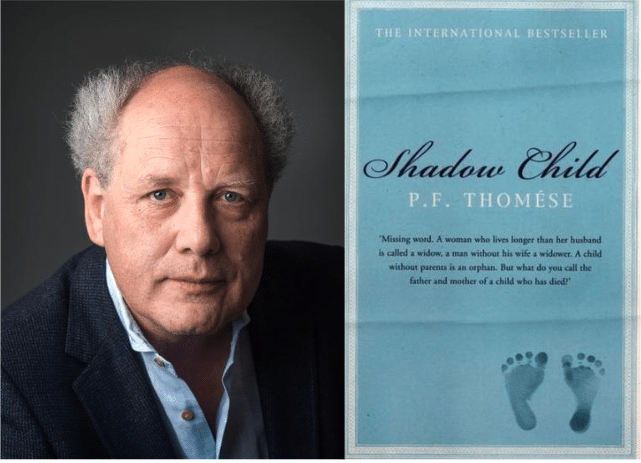

Must-read: ‘Shadow Child’ by P.F. Thomése

This year marks the twentieth anniversary of the publication of P.F. Thomése’s Schaduwkind. A best-seller in the Netherlands, it was published in 2005 as Shadow Child

in a translation by Sam Garrett.

In this compact book, which runs to barely a hundred pages, Thomése mourns the brief life of his baby daughter Isa. But these fifty short chapters defy categorisation. Shadow Child is neither a straightforwardly factual or fictionalised account of what happened to the little girl and her grieving parents, nor some kind of self-help guide, aimed at offering similarly afflicted families a clear route out of grief. It’s more of a free-form meditation in prose, at times abstract, poetic and philosophical, at others specific, mundane and direct. In a seemingly random order, the author tells us about coming home to an empty house to find ‘the little red blanket with the milk stain’, the joy of seeing his child being born, which has a perfect soundtrack in Charlie Parker with Strings, and ‘the flight into Egypt’ with the ambulance rushing the sick child to hospital.

But this is as much an exploration of language as it is a gentle examination of grief. Because as Thomése puts it, ‘if she still exists anywhere, then it’s in language.’ And so he sets about finding the words to describe the indescribable. Perhaps not surprisingly, this really speaks to me as a translator. Words often fall short, but they’re all we have and sometimes, if we persist, they give us great beauty and consolation.

P.F. Thomése, Shadow Child, translated by Sam Garrett, Bloomsbury, 2006, 112 pages

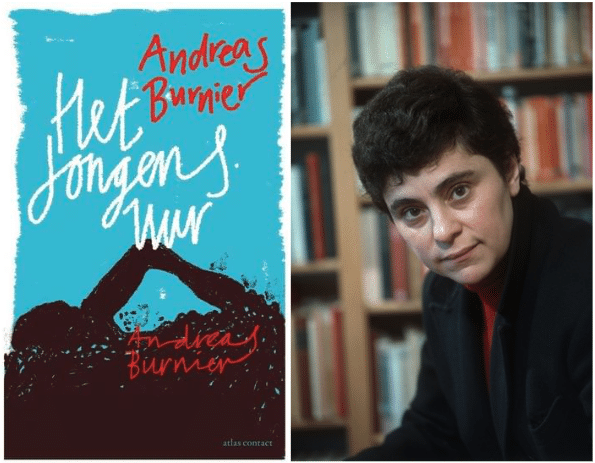

To be translated: ‘Het jongensuur’ by Andreas Burnier

A similarly short and intriguing book, Het jongensuur (Boys’ Hour) was first published in 1969. It was reissued last year and its author Andreas Burnier (1931 – 2002) is currently enjoying a long overdue revival in the Netherlands. Much of her work was ahead of its time in its exploration of issues of gender.

Inspired by the writer’s own experiences during World War II, Boys’ Hour tells the story of Simone who is forced to hide with a succession of adoptive families to avoid capture by the occupying Nazis. Each of her brief stays with these strangers from various social backgrounds (among them farmers, plumbers and intellectuals) reveals a little more about her uncomfortable relationship with her body: as she moves towards puberty, Simone desperately wants to be a boy.

In some ways, the war is incidental here, a backdrop to a multi-layered story about gender identity, class and the all-pervasive role of the church in Dutch society. Burnier paints a picture of a country riven by inequality that is at odds with the Netherlands’ reputation abroad. Add to this an unusual structure – the narrative starts in 1945 and ends in 1940 – and the result is a startlingly original work of fiction.

Andreas Burnier, Het jongensuur, Atlas Contact, 2015, 96 pages

Excerpt from ‘Het jongensuur’, translated by Laura Vroomen

Peat Village 1943

The poor, ramshackle farms were a sight to behold. Only one or two bigger landowners lived in hideous buildings of slightly more generous proportions. That said, the farmers were better off than most. Below them came the shopkeepers, the teachers, the labourers and the farmhands.

I lived with the plumber and his wife. With their twenty guilders a week, their half-acre of land for potatoes and beans and one sheep, they weren’t too badly off. Their small home with adjoining workshop stood at a junction of windy roads. Once a week Aunt sent me down one of these with a pan of soup for Mrs Kosse. This woman was truly destitute, with her eight children and a house reeking of pig piss.

One of the Kosse offspring, Annegien, was in the same year as me. She had lice, like all the other pupils apart from me and the assistant teacher’s twins. It was so bad you could see red, scaly patches through her thin blonde hair. Nobody would sit next to Annegien because she stank. That same stench, but worse, pervaded the house. All the Kosse children carried some of that smell to school. Aunt never used the pot in which I brought them the soup for anything else.

After handing the pan to Mrs Kosse, I’d slip out of the house as quickly as possible. Sometimes I’d chat to Annegien in the backyard. At school I ignored her, but when I turned up with the soup she’d be waiting for me. And because the person who gives depends on the one who receives, I had no choice but to be kind to her. I couldn’t very well pretend she didn’t exist in her own home.

But strangely enough I was also drawn to her stink and her poverty, the way you can enjoy a whiff of your own body odour. And when I’d see her little brother in his tattered clothes, stomping round the dung heap at the back of the house, I sometimes envied them their animal warmth.

It was cold in Peat Village. Most people here belonged to one of the three Reformed denominations, which meant a contempt and hatred for anything vibrant or even just warm. They despised each other and themselves for their innate sinfulness. They hated all that was human in their children, who were begot after a thrust and a grunt and a gruff ‘good night’.

It took me a long time to get my head round their view of the world. At first, I couldn’t even begin to imagine the meaning of ‘sin’, the sin for which you had to ask their God for forgiveness, night after night, on your knees beside your bed. But after six months I’d grown used to it, the way a dim-witted student, having heard his teacher explain it a dozen times, thinks he understands a mathematical proof.

Even the church was something you grew accustomed to.