Liberation of Belgium: More than ‘Cigarettes for Dad’ and ‘Chocolates for Mummy’

The commemorative ceremonies marking the liberation of Belgium, 75 years ago by now, spark memories of a joyful age in which friendly tanks triumphantly rolled down the streets. The unbridled enthusiasm Belgians witnessed back then is magnified today, and re-enacted here and there. However, those re-enactments only tell us half of the liberation story.

Re-enactors and bands with a knack for 1940s music are currently living the dream. The Andrew Sisters and Vera Lynn are back in vogue, we are all doing the jive, we’re donning our walls with Union Jacks, and when you look up, with any luck, you might just see a few Spitfires and Hurricanes once again soaring through the air. Nostalgia is reigning supreme.

Cheering crowds greet British troops entering Brussels on 4 September 1944.

Cheering crowds greet British troops entering Brussels on 4 September 1944.© Hardy, Bert, Imperial War Museum Collections

The liberation of Belgium, which began in September 1944, marked the end of four years of German occupation, and all the unpleasantness that went along with that. The arrival of the allied troops, whether they were British, American, Polish or Canadian, was obviously met with an exuberant response. The liberators not only brought the Belgians freedom, but also cigarettes for dad and nylon stockings or chocolates for mummy. Hundreds of young women would throw their arms around the necks of those well-nourished uniformed heroes, and some of them managed to cling on until this day: those ‘sweethearts’ married their ‘Tommies’, and have been living on British soil for much longer than they had ever lived in Belgium.

Collateral damage

Can we label fall of 1944 a joyous time? The Zonneman family, who lived on Abeelstraat in Ronse, 3 September, the day their city was liberated, that day will forever be remembered as the day their young son Eric was shot by a German. The boy, just nine years of age, was simply standing near the front door watching the occupying powers pull back.

Antwerp was liberated on 4 September 1944 by the British 11th Armoured Division.

Antwerp was liberated on 4 September 1944 by the British 11th Armoured Division.On 7 September, while a number of cities and towns were already celebrating, the Vandepitte family home in Gits, West-Flanders, happened to be in the firing line. Two Polish grenades hit the house. Son Georges Vandepitte was mortally wounded. Afterwards, the family counted the bullet holes in the façade: there were forty in total. ‘Collateral damage’ is what they would call that today: devastation in the margins.

German prisoners of war are taken away near Central Station in Antwerp.

German prisoners of war are taken away near Central Station in Antwerp.Two days before Hechtel in Limburg was liberated on 12 September, the Germans found Pieter Evers and his son Jef in the basement of their home and turned a gun on them outside, right by the front door.

On 8 September 1944 the city of Tielt was liberated by the First Polish Armoured Division under the command of General Maczek.

On 8 September 1944 the city of Tielt was liberated by the First Polish Armoured Division under the command of General Maczek.© CIty of Tielt

Another horrible case of ‘unintended injuries’ is the tragedy that played out on 16 September in Kaprijke in the Meetjesland region. The Germans were not prepared to be simply chased away by the Canadians and, therefore, there was a lot of shooting back-and-forth. Newly-weds Omer and Lima Neyt decided to hide in a pit they had dug with their own hands in the field next to Lima’s parents’ farm in Wauterstraat. The Canadians, however, thought Germans were hiding down there, and set fire to the pit. Omer, Lima and a neighbour were burned alive; Lima’s mother died two weeks after that. The young couple will be commemorated with a statue later this month right by the location where the dramatic events unfolded.

Reunion

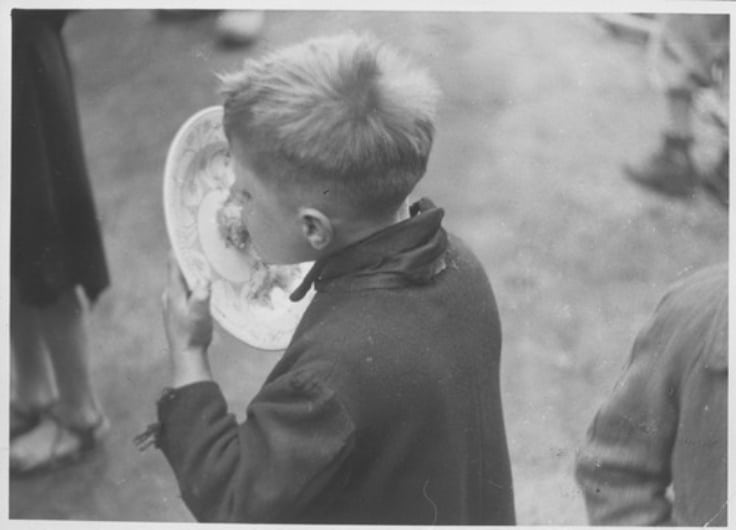

A time of joy? Hundreds of people were finally able to openly mourn those who were lost during the German occupation; hundreds more could begin to long for the return of a loved one they had not heard from for ages: forced to work in Germany, transported to a concentration camp, or ‘simply’ disappeared.

On 29 April 1945, Johan Eekman from Schaarbeek was found more dead than alive underneath a window in the Sandbostel concentration camp, located in the German state of Lower Saxony. At the time, he weighed just under forty kilograms and it would take a year for him to get back on his feet.

In 1943, the Germans sent Ghent brothers Richard and Armand Carlier to the Junker factory in Leipzig. During the bombing raids on the town conducted by the allies in February 1945, they managed to flee the factory. After a hellish trek – on foot and only wearing their ‘pyjamas’ – they found themselves in the American sector. Clutching a very austere food package, they were loaded onto a transport to Namen. In May 1945, they arrived home, and tears flowed down their faces unabashedly. Great happiness in Ghent, eight months after the city’s liberation.

Next: the V bombs

The liberation of Belgium lasted from 2 September 1944 to 4 February 1945 (the capture of the village of Krewinkel in the province of Liège). World War II would only officially end when the Germans surrendered on 8 May 1945.

The destroyed interior of Cinema Rex

The destroyed interior of Cinema RexAntwerp was liberated on 4 September 1944, but it was too early for the city to breathe a sigh of relief. German V bombs caused widespread material damage and claimed a great many lives. The first V bomb in the Antwerp agglomeration was dropped on 7 October 1944 in Brasschaat, the last on 30 March 1945 in Ranst. As a result of those raids, 4,483 lost their lives and another 7,266 were severely injured. The deadliest and most spellbinding V-bomb blast took place on 16 December 1944, when cinema Rex in De Keyserlei was hit. About 567 people were killed. Antwerp-born Henri Peeters survived the bombing because he had been sitting beneath a balcony, which prevented him from being crushed.

Wrong

Was the time of the liberation a joyous one? That depends which side you were on. Then ten-year-old Lieve Bogaert’s dad, from Sint-Amandsberg, was in charge of a German labour camp in Normandy, and was not able to return to Belgium on D-Day for obvious reasons. He and his family fled to Germany. On 1 May 1945 they were sent back home by the Americans. This turned out to be a traumatic journey for the girl who did not have a clue as to which film she was acting in at that time. Once they had arrived in Belgium, her parents were locked away in prison. Lieve was put in an orphanage, her brother in a home for abandoned children. No explanation was provided.

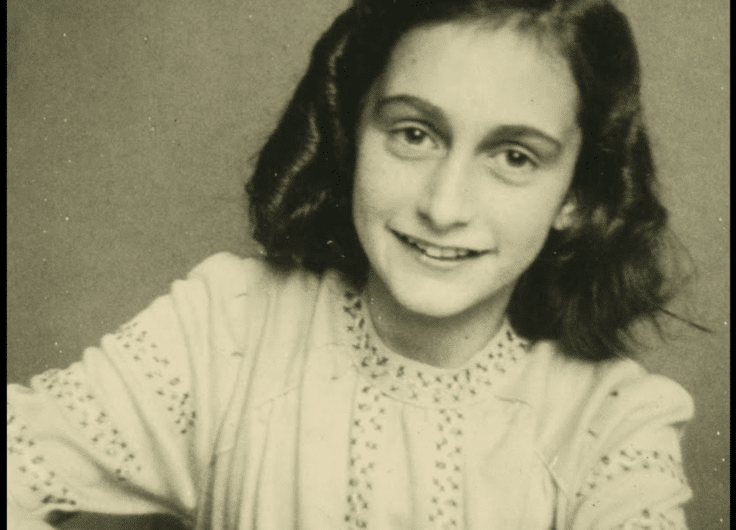

Head-shaving of a woman accused of sleeping with a German Soldier.

Head-shaving of a woman accused of sleeping with a German Soldier.© Carl Mydans/Time Life/Getty

On 4 September 1944, Alfons Van Opstal, from the border town of Koewacht, was taken to the headquarters of the White Brigade in Antwerp. There, he confessed he had been working for the Luftwaffe, and had been a member of the Black Brigade. Afterwards, he was severely beaten.

In October 1945, Martha Claessens from Leuven felt utterly shattered when she heard her sister Jetje being sentenced to death by the court martial in Brussels. Jetje Claessens had been one of the leaders in the fascist youth movement Dietse Meisjesscharen. Her punishment was later changed into life imprisonment, and later still, she immigrated to Argentina – a chivalrous solution to an awkward problem.

German soldiers in Antwerp were locked up in the lion cages of the Zoo.

German soldiers in Antwerp were locked up in the lion cages of the Zoo.© Imperial War Museum Collections

At the time of the liberation of Moerbrugge near Bruges, Robert De Groote, who was nine at the time, was forced to say goodbye to Karl Maier, a German soldier who had been quartered in his family home, and who he had come to regard as an older brother. Karl wept on that 8 September, and said he was terrified the Tommies would shoot him to shreds. Robert never heard from Karl again after that final goodbye. In 1980, he discovered Karl’s name on a tiny cross in the German cemetery in Lommel. Karl Maier had just turned 18 when he died on 9 September 1944 during the Battle for Moerbrugge. That too was part of the liberation of Belgium.