When the Netherlands Was Suffering Through the Hunger Winter

Although liberation was in sight, in the Netherlands the harsh winter of 1944-1945 became a symbol of the people’s suffering during World War II. More than twenty-thousand people died of hunger and cold. The severe wartime winter became known as the Hunger Winter.

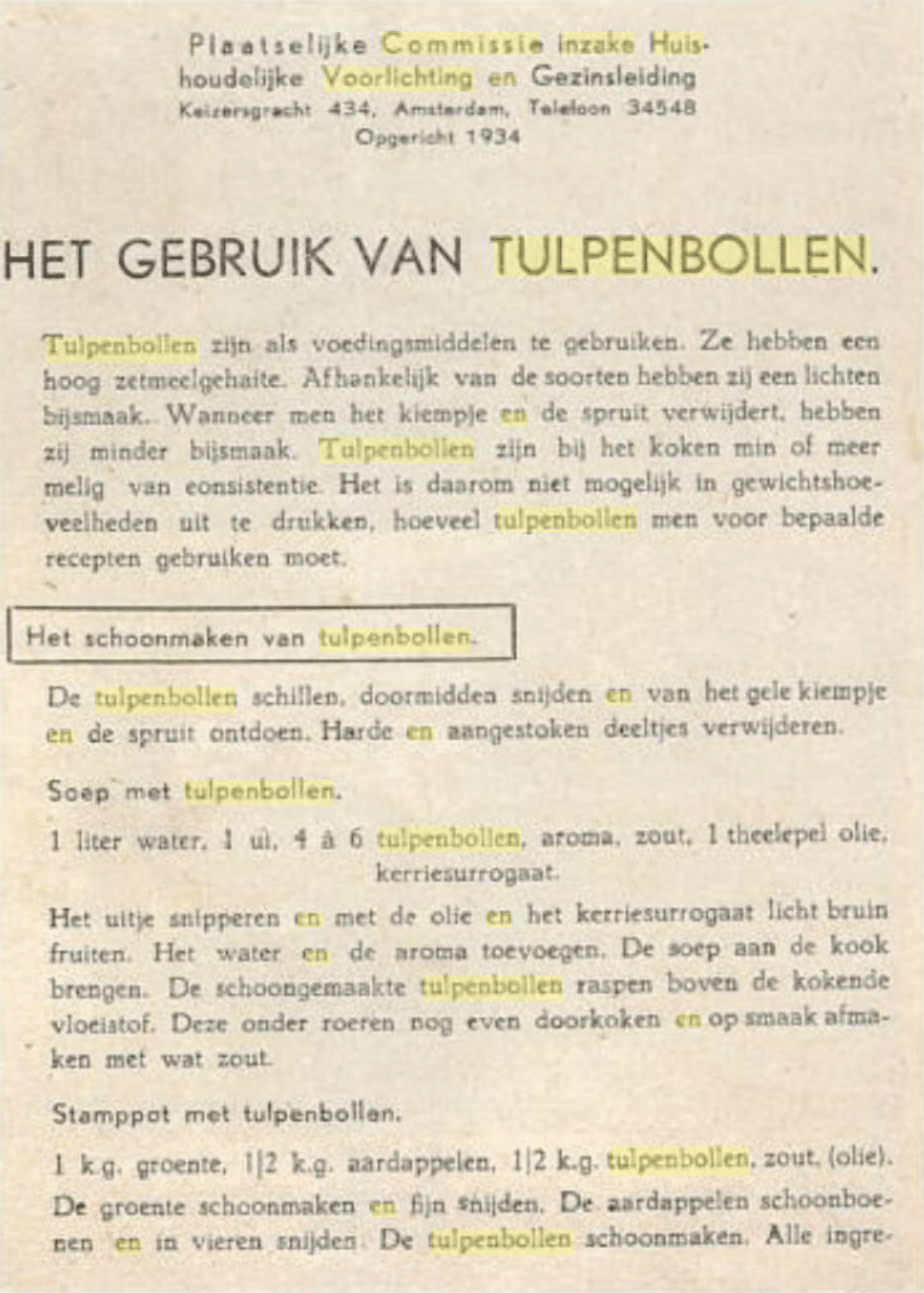

‘When the bulbs are properly hard and dry, they’re a delightful, nutritious delicacy, with a flavour similar to that of dried domesticated chestnuts.’ In the seventeenth century tulip bulbs were still seen as a luxury product, but in 1944 they had become an ingredient of biscuits, soups, purees, cakes and stews.

How to prepare tulip bulbs?

How to prepare tulip bulbs?The food shortage during World War II demanded a great deal of culinary creativity from Dutch women, who received good advice from the government, doctors and national newspapers. In 1945 the Amsterdam Local Committee for Domestic Education and Family Management published a cook book on the use of tulip bulbs. After all, when people are really hungry, they will eat everything. And eating had kept the population in the Netherlands occupied throughout the war. The food shortage compelled people to be thrifty and the governments to come up with alternative distribution systems. Real famine, however, only became an issue in the Netherlands after the end of the war. Liberation brought the most difficult trials for the civilian population.

Dolle Dinsdag celebration (5 September 1944) in Rotterdam. The city was not to be liberated until May 1945.

Dolle Dinsdag celebration (5 September 1944) in Rotterdam. The city was not to be liberated until May 1945.© Wikipedia

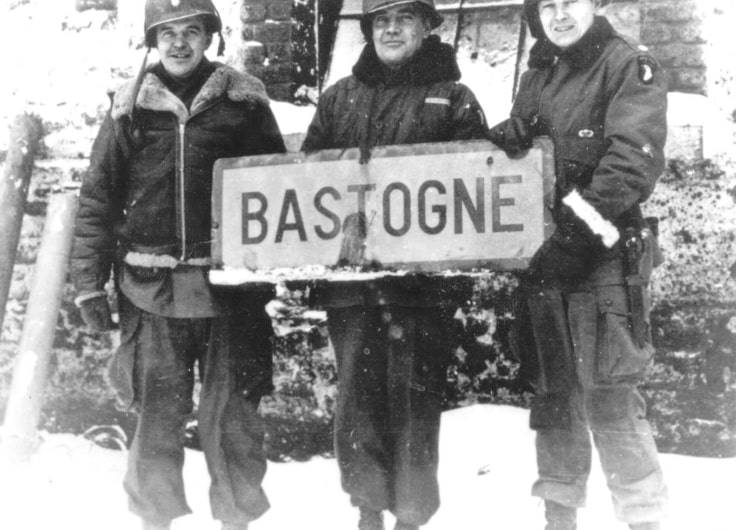

After the Normandy landing at the start of June 1944, the Dutch population trusted that the war was almost over. On 5 September – known as Dolle Dinsdag or Mad Tuesday – the German soldiers fled en mass. People expected to welcome the Allied troops at any moment. Aiming to make things easier for them, the Dutch government in exile called for a complete rail strike on 17 September, ‘in order to hinder enemy transport and troop concentrations as far as possible’. But the liberation of the Netherlands didn’t go as planned and in autumn 1944 the frontline came to be situated in the middle of the Netherlands. For the part of the country still under occupation, this was the beginning of the most difficult time in four years.

German soldiers leave after rumours about the imminent arrival of the allies.

German soldiers leave after rumours about the imminent arrival of the allies.© NIOD

Although they fully understood that this would raise difficulties, the Dutch government refused to withdraw the call for a strike. The railways remained unused. The German occupier reacted with similar actions and stopped all food transports to the west of the country. This cut off the population in the occupied area from the outside world. Food, fuel and other supplies no longer entered the region, with inevitable consequences. Although the exact figure remains unknown, it’s likely that around 22,000 people died of hunger, cold and disease, all within a couple of months.

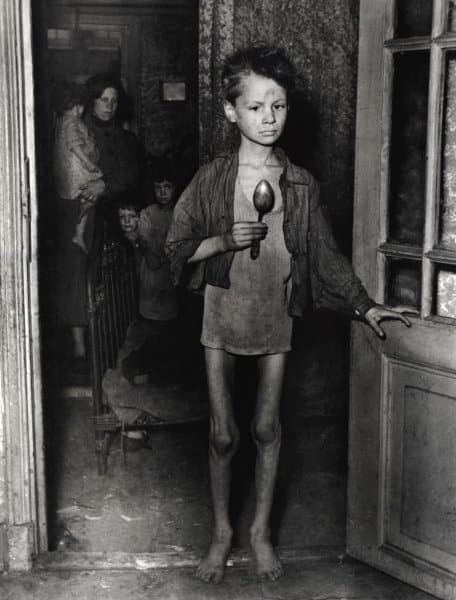

Starving boy in Amsterdam, 21 December 1944.

Starving boy in Amsterdam, 21 December 1944.© M. Meijboom, collection Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam

The winter of 1945 was also severe and the daily life of the Dutch people primarily revolved around survival. Men remained at home as far as possible – fearing arrest and transfer to Germany. Women and children went out to gather food or scraps. Driven by hunger they left the cities for the countryside to buy food from farmers, often in exchange for clothing or jewellery. Family members outside the occupied area sent postal packages of food. Then the German occupiers dealt the population a further blow, prohibiting packages of more than 200 grams. By the end of the winter many of the city residents were too weak or ill and the searches for food decreased in number.

Queuing up for food

Queuing up for foodAid came only bit by bit and initially only from the Netherlands itself. Family members tried to get food into the occupied region as often as they could, undernourished children were placed in foster families in the countryside and in October 1944 soup kitchens that had closed earlier in the war reopened. After a long time in a queue, people were able to obtain a modest meal there, albeit of low quality.

Children desperately looking for food in The Hague.

Children desperately looking for food in The Hague.International actions only started up at the end of the war. The first foreign aid came from the Portuguese Red Cross, followed in January 1945 by a consignment from Sweden. They were used to make what they termed white bread, which in fact only slowly found its way to the hungry people. Only a few days before the liberation of the Netherlands did British planes drop food. With the special permission of the Germans, packages were deposited on derelict land. The relief was enormous, especially a few days later, on 5 May 1945, when the occupation ended.

A 115 Squadron Lancaster dropping food packages over the Netherlands.

A 115 Squadron Lancaster dropping food packages over the Netherlands.The consequences of this catastrophic hunger winter remained visible for years. Although there was soon an end to the extreme hunger, it was a while longer before the free market for all foodstuffs was restored and the effects of the famine on the health of the population were discernible for years to come. The photos of emaciated children in search of food were exhibited and distributed soon after the war. They very fittingly depicted the bitter misery which part of the Netherlands suffered at the very end of World War II.