Can we view 1945 as the zero point of the world we live in today, 75 years later? Certainly, much for which a framework was created at the time – from the welfare state to economic growth, from the moral manifestation of universal human rights to international alliances – is under threat today. Former editor-in-chief Luc Devoldere believes there isn’t much security anymore. ‘The post-war consensus building needs some fundamental maintenance.’

Cheering crowds greet British troops entering Brussels, 4 September 1944

Cheering crowds greet British troops entering Brussels, 4 September 1944© Wikipedia

In May 1945, when the weapons fell silent in Europe and the orgy of celebration and revenge was over, the old continent was able to take stock of its moral and material bankruptcy. It was a year of destruction, rescue and chaos. Hundreds of thousands were left licking their wounds far from home. Would they ever see their homes again? People chose sides, their political camp, or they ended up in an actual camp. At the same time, 1945 was the year of hesitant construction. Of starting over. Of becoming wiser. In London that year, the philosopher Karel Popper published his most important book, The Open Society and Its Enemies. He wrote in defence of liberal democracy against the totalitarianism of the 20th century – from New Zealand, where he, an Austrian Jew, had fled in 1937. The German philosopher Theodor W. Adorno argued that it was barbaric to write poetry after Auschwitz. And in 1962 Remco Campert could hardly believe that, as a 16-year-old kid in 1945, he could write about a pure white birch tree while ‘the world around me was drinking and whoring’.

After 1945 many felt that everything had to be newly rebuilt. Roberto Rossellini filmed Germania Anno Zero (1948) in the ruins of Berlin. Years later, Ian Buruma wrote Year Zero. A History of 1945 (2015).

Can we view 1945 as the zero point of the world we live in today, 75 years later? Certainly, many things were put into motion then – from the welfare state to economic rebirth and growth, from decolonisation to the moral manifestation of universal human rights, bonds and alliances (Benelux, NATO and the European Union) – that seem to be under pressure now, or at least in need of complete reform.

American President Truman signs the NATO treaty in 1949

American President Truman signs the NATO treaty in 1949© Wikimedia Commons

Maybe the term zero point is too strong. There are some other reference points to consider. The British historian Eric Hobsbawm wrote about the Short 20th Century of 1914 to 1991 (in contrast to the long 19th century that ran from 1789 to 1914). In fact, the “Great,” exclusively European, War that started sleepily in 1914 only really ended with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the implosion of the Soviet Union and real Communism in Europe. This implosion also marked the end of the Cold War that had started in 1945. Others see 1918 as a point of no return because of what happened with the Czar, the Austrian and German emperors and the Ottoman Empire: four empires disappeared.

Others point to the Thirty Years of Glory (Trente Glorieuses) (1945-1973), the period of staggering economic growth and prosperity that fuelled the first oil crisis. The Netherlands can claim that its war only ended in 1949 with its loss of sovereignty in Indonesia.

Still, there are sufficient reasons to take 1945 as an important reference point for Europe and, indeed, of the Low Countries. We are now a human lifetime – 75 years – further along.

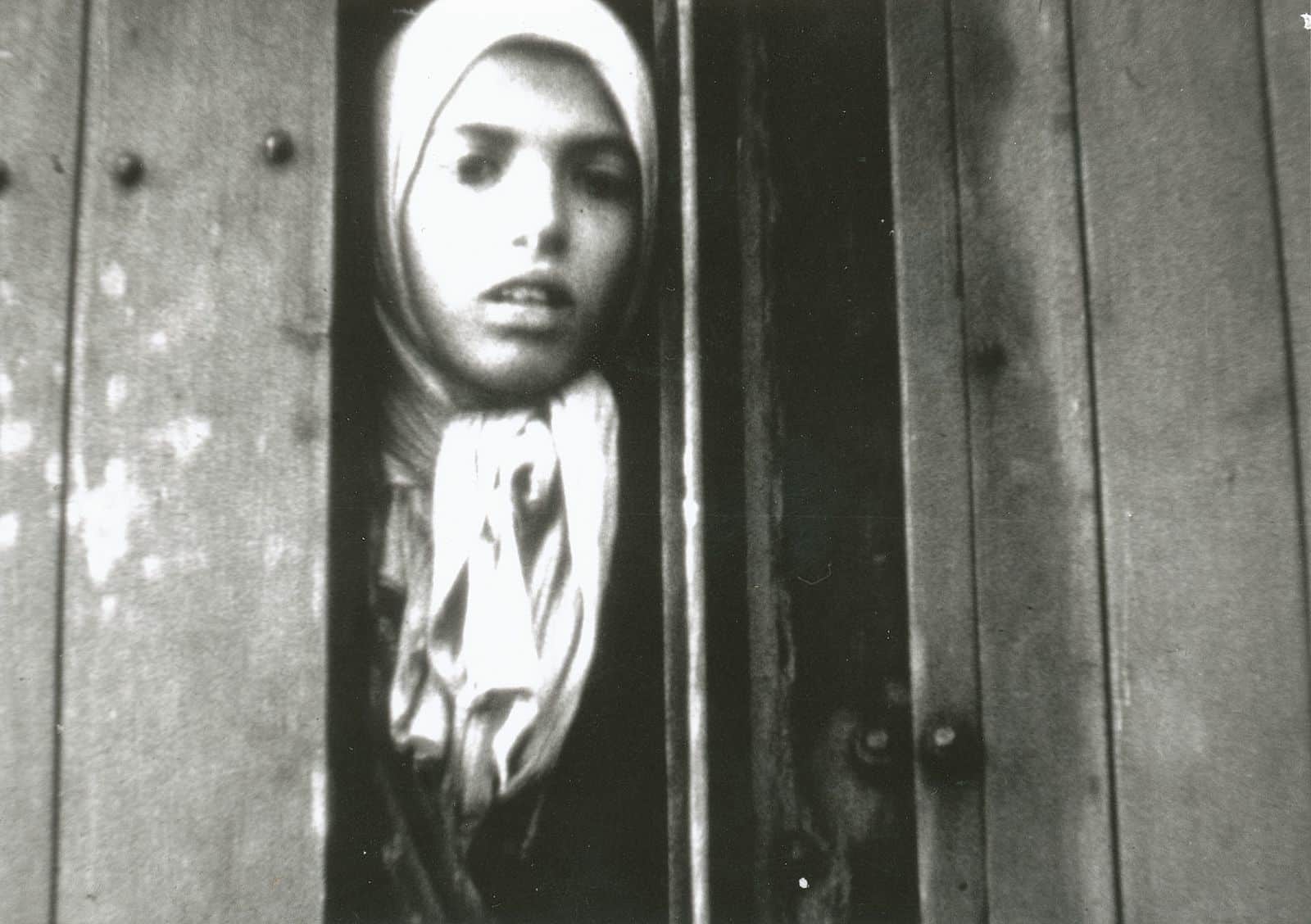

Dutch Roma girl Anna Maria (Settela) Steinbach on the train from Westerbork in the Netherlands to the Auschwitz concentration camp, were she was killed.

Dutch Roma girl Anna Maria (Settela) Steinbach on the train from Westerbork in the Netherlands to the Auschwitz concentration camp, were she was killed.© Wikipedia / Still from film by Werner Rudolf Breslauer

The past of the war, with its collaboration and repression, its resistance to the occupier, the trauma of Jewish deportation and the Holocaust does not seem to have been fully processed. The commemorations limp along and WWII continues to haunt our literature.

Harry Mulisch, the child of a Jewish mother and an Austro-Hungarian collaborator, can rightfully say: ‘I am the Second World War.’ In his debut Marcel (1999) Erwin Mortier could write: ‘The cellar preserved, the attic released.’ In the Spring of 2020, he published a sequel to this – his – family history: The Immaculate. And Aaron Grunberg, a Dutch Jew, continues to clarify his position about the Holocaust (Occupied Territories and With Us in Auschwitz: Testimonies, 2020) (Bezette gebieden en Bij ons in Auschwitz. Getuigenissen, 2020).

Maybe we will need to wait a century to put the Second World War in its proper perspective

Maybe we will need to wait until 2045, a century after the war, once all the eye-witnesses have disappeared, to put this war in its proper perspective and return it to history, as happened in 2018 with the First World War. By 2045 will Germany have left its Vergangenheitsbewältigung, the difficult processing of its wartime past, behind and said goodbye to the moral guilt that still binds the country today?

One hundred years on, will the existential discussions of the Holocaust still be conducted in terms of specificity or uniqueness? Of course, the Holocaust was a very specific genocide but is it unique in the sense that it can escape comparisons with other genocides and be withdrawn from history itself?

What is true in any case is that there is still a great deal of historical research about World War II to come. But a balance must be found between ritual commemoration and historical method. There is, to put it bluntly, a duty to record history, not a duty to remember.

The fall of the Berlin Wall, 1989

The fall of the Berlin Wall, 1989© Wikimedia Commons

The End of Post-War

The fall of the Berlin Wall did not signal the definitive victory of liberal, secular democracy which goes hand-in-hand with a free market economy, as Francis Fukuyama thought with his “end of history”. In fact, we have now come to The End of Post-War, the political and social consensus in Europe attained after the catastrophic Second World War and guaranteed by the Pax Americana.

The believers in this consensus declared that they would leave their nationalism behind them and that Europe would become more unified, would become one, that all ‘nations’ worldwide, would, in the end, be ‘united’. The political elites made a pact with the ‘people’.

Ground Zero with the remains of the World Trade Center after the September 11 terrorist attack in 2001.

Ground Zero with the remains of the World Trade Center after the September 11 terrorist attack in 2001.© U.S. Navy photo by Chief Photographer's Mate Eric J. Tilford

But after 2000, when the two planes flew into the Twin Towers, nationalism and religious fundamentalism are still alive and well. The elites have lost any feeling for the ‘people’ who are beginning to flee from them towards the siren song of ‘populists’.

And here we are in the present-day. The post-war structures need fundamental maintenance.

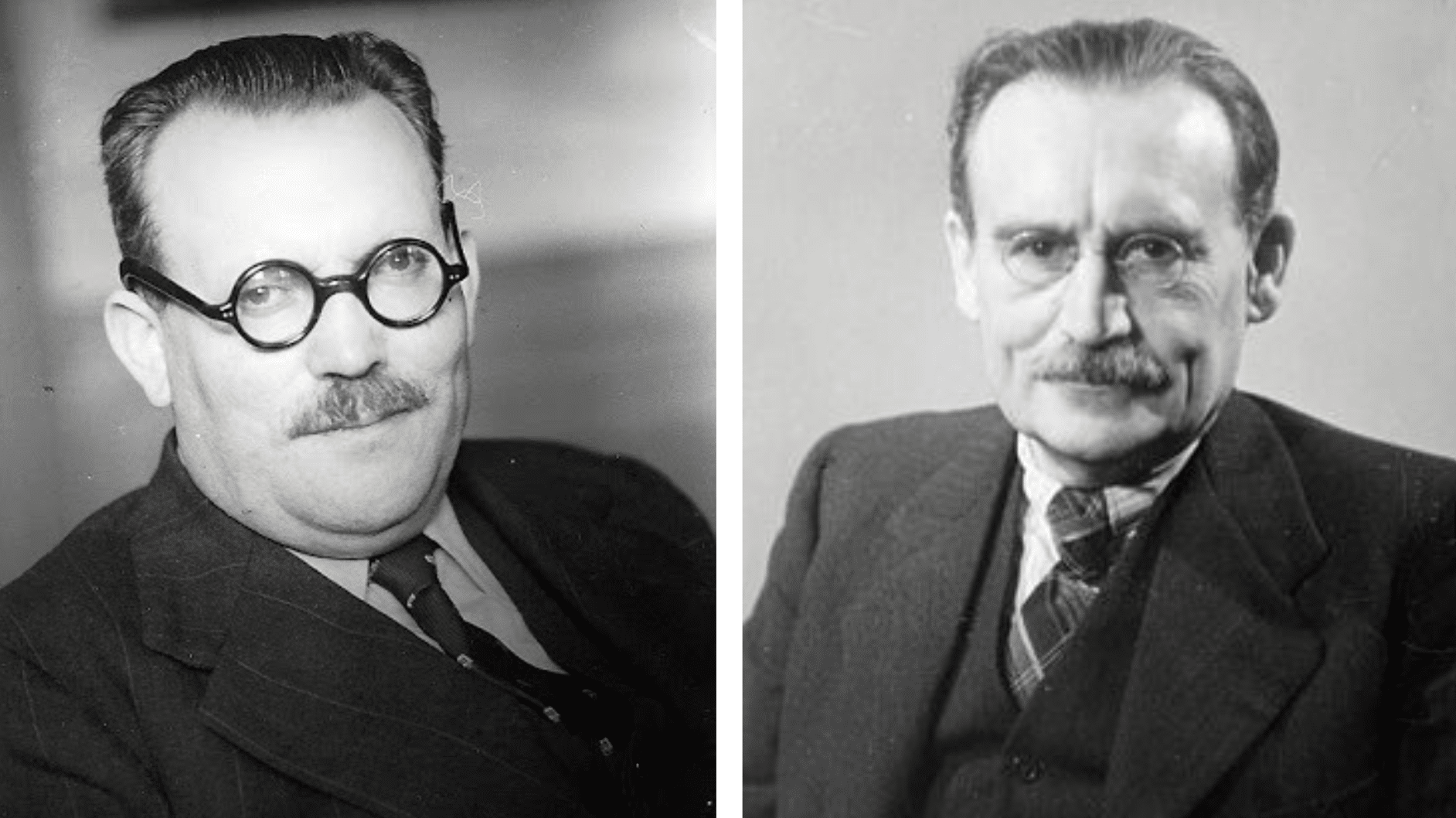

Take the structure of social security: a veritable cathedral, maybe even a work of art. An expensive construction, in any case, that protects us, certainly in the Low Countries, against sickness, unemployment and old age through a framework of insurance, benefits and pensions. This monumental structure brought prosperity and emancipation in its wake. It connected people and stabilised the economic and political systems. It is a social pact that seals an exchange between employers and unions, between labour and capital. In the Netherlands and Belgium, the architects were the pragmatic social democrats Willem (‘Daddy’) Drees and Achiel Van Acker (J’agis et puis je réfléchis) (‘I act and then I reflect.’) Anno 2020 and the system is under pressure. It seems that it might not be self-evident after all and certainly not eternal. It is becoming more expensive. Yet it is crucial to preserve it through intelligent reform and careful pruning.

Achiel Van Acker and Willem Drees, the architects of the system of social security in Belgium and the Netherlands

Achiel Van Acker and Willem Drees, the architects of the system of social security in Belgium and the Netherlands© Amsab / Wikipedia

The unions the Low Countries fell into after 1945 are also in need of some thorough maintenance. The Benelux seems to have been overtaken by the unification of Europe which, in its turn, is also faltering. Not so long ago, a former Belgian Prime Minister said Europe was an economic giant, a political dwarf and a military worm. The worm idea was new. The French president Emmanuel Macron felt free to refer to NATO as ‘brain dead’ because the European countries, except for France, have been too lazy for too long under the umbrella of NATO and especially America, and are not sufficiently prepared to defend themselves. That is the case a fortiori in Europe. The war in the former Yugoslavia was not that long ago. Macron may have the right to be angry when yet another thirteen French soldiers are killed in Mali. Maybe we should discuss a fairer sharing of the burden with him.

On the one hand, Europe is a construction of enforced rules and procedures that are followed even by non-members of the Union such as Switzerland and Norway. On the other hand, the EU remains a soft power

that cannot even guard its borders or agree about the repatriation of the wives and children of IS-fighters, never mind the fighters themselves.

The Europe of the offices is a compromise-mill with a serious deficit of democratic legitimacy. Yet it is an imbroglio that works, that turns out to be stronger than expected and continues to hobble along, clumsily, from event to event.

The European Parliament in Strasbourg

The European Parliament in Strasbourg© European Parliament

After 1945 the nation state and certainly nationalism itself were suspect. A European union was supposed to put an end to the centuries-long violence between European countries, most particularly between France and Germany. People forget that the first loyalty of citizens remains with their nation states, particularly when it comes to something like social security. The system of social security presupposes solidarity and the first and strongest bond is with the nation state. The European bond does not offer that kind of security.

The United Kingdom left the European Union because it clings to its own sovereignty. However much one tries to relativize or rationalise it; citizens continue to give importance to the sovereignty of the nation state in their political conceptions of their own country. This awareness of ‘nationhood’ is stubborn. It is much stronger in the Netherlands than in Belgium or Flanders. The least that you can say about Belgium is that, together with Italy, amongst others, it is one of the weakest nation states in Europe. Moreover, the nation is not aligned with the state in Belgium. Flanders is a paradox; a nation, but with a complex and generally weak national identity that is not shared equally by everyone.

Patrice Lumumba, the first Prime Minister of Congo, delivered his famous attack on Belgian colonialism in the presence of King Baudouin in 1960.

Patrice Lumumba, the first Prime Minister of Congo, delivered his famous attack on Belgian colonialism in the presence of King Baudouin in 1960.Public Domain

We can also speak here about the loss of the colonies that were unsustainable after the war. In Indonesia, the people had already seen how the Western colonisers, untouchable for so long, were beaten and humiliated by the Japanese who, like the Indonesians, were Asians. In Congo, colonisation would continue until 1960. And it took longer until the spirit of decolonisation got underway. In this, too, the Netherlands was quicker than Belgium. Noteworthy is the fact that, currently, it is primarily the Congolese diaspora that cross-examines the Belgians. It’s the second or even the third post-colonial generation that radically imposes its perspective and voice. Henk Wesseling, a historian of the ironic school in Leyden, who finds it a pity that today more importance is placed on remembrance than history, could write laconically in Europe’s Colonial Century. The European Colonial Empires of the Nineteenth Century (Europa’s koloniale eeuw. De Europese koloniale rijken in de negentiende eeuw) (2003): ‘In this book, several statements show just how much Europeans were convinced of their own superiority at the time, and believed they had the right, perhaps even the duty, to colonise and to bring civilisation to people who were living in the dark. There is also sufficient in this book to prove that reality was different. It is only necessary to open a newspaper to see that, nowadays, more attention is given to the latter than the former viewpoint.’ Today, this viewpoint is increasingly disputed.

This article is the English translation of the introduction to the book Nulpunt 1945 (Zero Point 1945, Ons Erfdeel vzw, 2020).