Moulding Life: Artists Craft with Fungi and Bacteria

From pathogens to nature’s binmen – fungi, bacteria and algae have many functions and associations. Artists and designers are increasingly embracing the sensory properties and sustainable potential of these obstinate microorganisms. Say hello to bioluminescent fungi and microbial weaving.

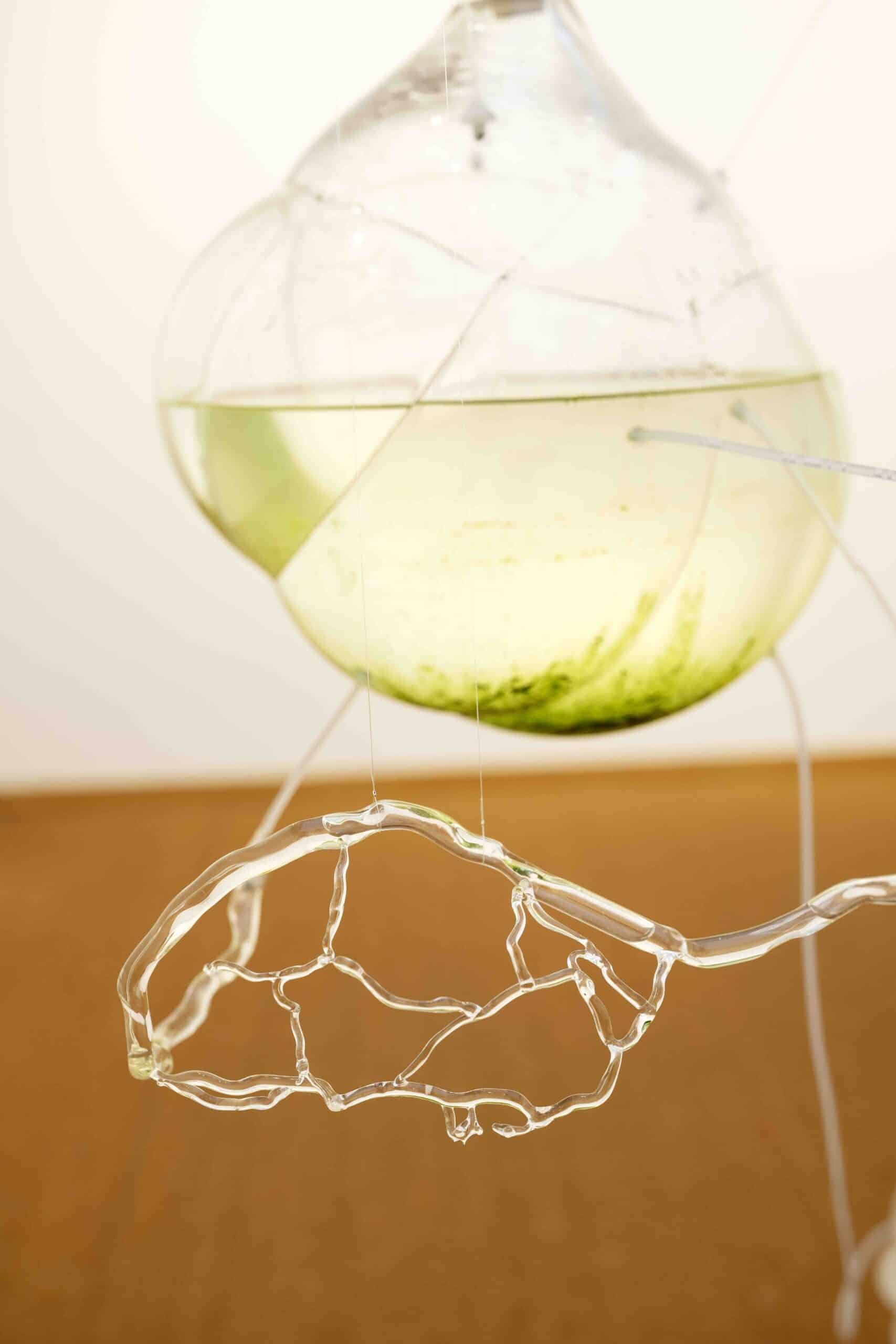

The glass balls of Feeling Strained (2023) appear to contain lunar landscapes, but it’s actually yeast. These microorganisms grow as part of this installation by Belgian artist Isabel Fredeus (b. 1991), but they’re not the only ones growing inside the glass balls. Because their vessels are contained but not sterile, other life forms can also make a temporary home there, resulting in the creation of small-scale alienating landscapes. Feeling Strained is simultaneously close to nature as well as a slice of distant science fiction.

‘Feeling Strained’ (2023) by Isabel Fredeus is simultaneously close to nature as well as a slice of distant science fiction.

‘Feeling Strained’ (2023) by Isabel Fredeus is simultaneously close to nature as well as a slice of distant science fiction.© Cedric Verhelst

The (re)discovery of the microorganism

Microorganisms have miraculous properties that are being (re)discovered by more and more people, from scientists to laymen. A huge audience has been reached through things like the documentary Fantastic Fungi (2019) of Louie Schwartzberg, as well as the book Entangled Life (2020) by biologist Merlin Sheldrake. According to the cataloguing website Goodreads, around 30,000 users have already read Sheldrake’s book – a considerable number for what seems like a niche subject.

This audience has become more acquainted with what Sheldrake calls the Wood Wide Web – a complex, underground network of communicating fungi. The more common term is mycelium. The Flemish-Dutch duo Wes Nijssen (b. 1985) and Bram van Wichelen (b. 1984) have made an artistic translation of it through their interactive light installation Mushlooms

(2023). Art, science and sensory experience come together in the installation. Using a mycelium-like network of threads, fungus-shaped objects light up in response to environmental factors such as air pollution. It seems a bit surreal at first, but there really are mushrooms that glow in the dark.

Art, science and sensory experience come together in the interactive light installation ‘Mushlooms’ (2023) by Wes Nijssen and Bram van Wichelen.

Art, science and sensory experience come together in the interactive light installation ‘Mushlooms’ (2023) by Wes Nijssen and Bram van Wichelen.© Wes Nijssen / Bram van Wichelen

Life, death and stubbornness

Anyone who has seen Fantastic Fungi knows what television can do that a book can’t – treating the viewer to spectacular time-lapse images of emerging fungi. They are presented almost like flowers blossoming. In other words, microorganisms can be incredibly sensory as well, but this isn’t the only aspect of fungi that inspires artists. Fredeus, for example, says that the mycelium bridges the gap between life and death. Certain fungi clear away dead plant material, making them nature’s very own binmen. They are minuscule, but able to manage vast swathes of land.

This interaction between macro and micro is an important theme in Fredeus’ practice. Another example of this is that microorganisms are also abundantly present in the human body, and are particularly important for keeping our digestion on track. Moulds are also often associated with dirt and disease, an association their fellow microorganisms – bacteria – also have. This kind of tension plays a role in the art and design that makes use of, or is inspired by, these special life forms.

Another charming aspect of microorganisms is their stubbornness. Seaweeds and algae, for example, are sometimes seen as plants, but they aren’t. Fungi have only been considered a separate kingdom for a short time, now residing next to fauna and flora as funga. For convenience’s sake, they were often bundled in with flora, but funga have commonalities with both animals and plants.

Microorganisms are hard to classify, which is attractive to artists, designers and other makers who work in interdisciplinary ways

It’s not difficult to imagine how this tricky classification is attractive to artists, designers and other makers who work in interdisciplinary ways. For example, Fredeus has learnt from researcher Elise Elsacker how to grow mycelium herself, to investigate its sculptural qualities. The hyphae in Fredeus’ installations show different behavioural patterns than they do in petri dishes. In turn, such artistic discovery provides Elsacker with starting points for new experiments – talk about interaction. Artists, designers and other makers regularly collaborate with scientists – but more about that later.

A lunarlandscape made from mould

Fredeus, Nijssen and Van Wichelen are not the first artists to be fascinated by microorganisms, there is already quite a tradition in this field. Fungi, seaweeds and algae have been used for decades as subjects and as materials for works of art. For example, some Baroque still life depict mushrooms and in the nineteenth century, many drawings were made using fungi, in part as a result of the fact that fungi were being observed more and more seriously in a scientific sense.

Since the 1950s, microorganisms have also been used as material for works of art. For example, American artist Gordon Matta-Clarke’s The Land of Milk and Honey (1969) is part of the Stedelijk Museum’s collection in Amsterdam. The artwork – a kind of fossil or moonscape behind glass – is indeed made using two unusual materials – milk and honey. If you’re wondering how that’s going, there’s now a large layer of mould growing on it. This is of course quite filthy, but at the same time very intriguing – a work of art that very slowly changes shape, even years after the untimely death of its creator in 1978.

From fear to imagination

A number of artists in the Low Countries have also been working with microorganisms for a long time. In the Netherlands, for example, Lizan Freijsen (1960-2024) has been inspired by fungi since the 2000s. This fascination appears to go back to her youth, holidaying in a chalet in the woods, “There were mould stains on the ceiling above my bed, which gave me a kind of unsafe feeling. I would look at it until the point I could see something in it, and only then could I go to sleep. I used my imagination to transform my fear,” she says in an interview with art magazine Palet. This is a typical combination of the mixed feelings that many people have towards microorganisms. When the fear is overcome, the space for fantasy is created.

Freijsen's fascination with mould is manifested in her large, hand-tufted carpets such as ‘Van Dortmoss’ (2018).

Freijsen's fascination with mould is manifested in her large, hand-tufted carpets such as ‘Van Dortmoss’ (2018).© Lizan Freijsen

Freijsen’s fascination with mould is manifested in her large, hand-tufted carpets. The colours are based on specific fungi and she uses their growth patterns as a source of inspiration for the final shape of each piece. The art looks both natural and handmade – like the fungi you might see on a tree stump or under a microscope, and at the same time inviting to the touch because the fabric looks so soft. The tactile experience is therefore important to Freijsen. You could consider it a way to make renewed contact with the nature that you previously kept at arm’s length, perhaps because you experienced it as dirty. Could there be a better (unintended) metaphor here for how many people rediscovered the nature around them thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic?

Collaborating with bacteria and algae

For Freijsen, fungi are a source of inspiration, but she does not use them as a material. This is different to the Belgian artist AnneMarie Maes (b. 1955), who combines art and science, the result of which can be seen in the ongoing Laboratory for Form and Matter

(since 2016). This laboratory began with a fascination for bacteria and natural networks in a broader sense. She has now investigated a wide range of techniques, materials and processes including 3D printing, laser cutting and making biotextiles using microorganisms. Her laboratory’s aim is to develop new materials. However, in an interview with Hilde Van Canneyt she noted, “I feel like an artist first and foremost. For example, I don’t know how I would approach the same topics as a scientist. I need to work visually.”

AnneMarie Maes, ‘L’Origine du Monde’, installation, 2020. Installation with living cyanobacteria colonies that photosynthesize during the duration of the exhibition, absorbing CO2 and releasing oxygen. The colour green deepens as the bacteria multiply.

AnneMarie Maes, ‘L’Origine du Monde’, installation, 2020. Installation with living cyanobacteria colonies that photosynthesize during the duration of the exhibition, absorbing CO2 and releasing oxygen. The colour green deepens as the bacteria multiply.© AnneMarie Maes

This need is evident from the subsequent successes the laboratory has had, including the installation L’Origine du Monde (2020) and the two-part exhibition Sensorial Skins + Woven By Nature (2021), in which Maes exhibited sculptures and textile artworks made from biological materials constructed using bacteria and algae. Just like with Freijsen, this produces attractive-looking textures, but in this case, there is an extra dose of spectacle – the fact that such tiny, mysterious organisms can weave such enormous expanses of fabric.

AnneMarie Maes, ‘Sensorial Skins’, since 2016, installations and sculptures made from bacterially produced leather.

AnneMarie Maes, ‘Sensorial Skins’, since 2016, installations and sculptures made from bacterially produced leather.© AnneMarie Maes

Alternative forms of research

In addition to making new materials, microorganisms have a wide range of practical applications, from antibiotics to cleaning up oil spills. They can also be used to break down plastics. It’s therefore not surprising that designers, who are more environmentally conscious than ever before, are also drawn to working with funga and bacteria.

I have previously written about the Dutch biodesigner Emma van der Leest (b. 1991) for the low countries (Jan 2020). She has created her own lab in a former swimming pool, using mostly recycled facilities. For example, the discarded brewer’s fridge turned out to be an excellent location for growing bacteria. These aren’t the only microorganisms Van der Leest works with, she also focuses on fungi and algae. She uses these for all kinds of sustainable purposes, including bacterially made vegan leather.

You could call Van der Leest’s and Maes’ practice an alternative type of research, which seems to be becoming increasingly popular among artists and designers. This is probably also to do with a broader development and a growing realisation that you don’t have to be a scientist to work with microorganisms. You can very easily find instructions for all kinds of DIY projects online. You can cultivate microorganisms for a variety of purposes, from removing stains and bad odours, to protecting your flowers against unwanted insects. In fact, various websites promise that there’s really no need for a laboratory at all.

A prototype of ‘Growing Materials’, Emma van der Leest’s plastic replacement made from fungi and hemp.

A prototype of ‘Growing Materials’, Emma van der Leest’s plastic replacement made from fungi and hemp.© Emma van der Leest

The non-sterile environments in which Fredeus presents Feeling Strained also point in this direction – an artistic practice does not necessarily have to conform to scientific conventions. As exciting as these developments are, there is one caveat: it’s not always clear whether projects involving microorganisms, especially when it comes to biomaterials, can be reproduced easily or scaled up. Are they carried out with the intention of eventually being put into production, or are they more speculative and exploratory in nature?

From academy to Dutch Design Week

Of course, we don’t have to demand that artists and designers scale up production. Their experiments can of course remain explorations, which don’t necessarily have to have practical results. But with all the discussions surrounding the state of the environment, it’s tempting to imagine a future where economies of scale can be achieved, and sustainable alternatives for materials and products can become the norm. In any case, a large network, a mycelium you could say, has emerged in the Benelux around working with biological materials, and the overlap between art, design and science. An important player here is the Design Academy Eindhoven, which attracts students from all over the world, who sometimes remain to teach there. Although Emma van der Leest didn’t get her degree from Design Academy Eindhoven, she did teach there. There is even an MA offered in Biodesign.

A large network has emerged in the Benelux around working with biological materials, and the overlap between art, design and science

Microorganisms find their way into art and design education, as is also evident from the BIO MATTERs research program at the AKI ArtEZ University of the Arts in Enschede. On the website, they talk about “DIY biology, biohacking, life sciences and speculative ways and methods of working with living bodies”. The goals are multifaceted – concretely, biomaterials are developed, but in a broader sense the program is about preparing for “new theoretical and practical insights into how to live with constant uncertainty about the future”.

Such issues trickle down to a broader audience, partly thanks to the busy Dutch Design Week (DDW) in Eindhoven. As part of DDW 2023, Dutch artist-designer Arne Hendriks (b. 1971) set up a space called Buro Miso. Visitors could learn to make and eat miso – fermented soy paste from Japan. According to Hendriks, miso can be used as a way to smooth the path of social change – including things like the clean energy transition and reducing overconsumption. In an interview on the DDW website, Hendriks explains this idea, “A little a jar of miso – the story and the metaphorical power behind it, will hopefully help bring change to bear. Simply because it makes us look at the essential aspects of life differently. As an artist, I believe it starts at that very fundamental level. The rest will come later.”

That last sentence may sound a bit speculative, but in 2020 Hendriks took concrete steps with his Mycelium Pigeon Towers, an ongoing project in Amsterdam in which he has built pigeon towers using waste from oyster mushroom farms. Mixed with the pigeon droppings, this produces fertile soil on which fungi grow that can be safely picked and eaten.

And since fungi, algae and bacteria are gaining ground in the creative sector, Hendriks’ sustainable “later” may come sooner than you think. The question then is whether bacteria, algae and fungi will have become the standard for many materials and products. Fear not – artists will undoubtedly continue to find new ways to relate to the alienating charms of microorganisms.

AnneMarie Maes currently has two exhibitions running based on microorganisms. Her solo exhibition Matter of Kinship can be viewed until April 30th 2024 at Fundação da Casa de Mateus (Vila Real, Portugal); along with Sensorial Skins.

Lizan Freijsens piece The Fungal Wall (2021) can be seen until 2030 in Micropia (Amsterdam), the world’s first museum of microbes.

Arne Hendriks’ Mycelium-Waste-Pigeon-Towers can be seen in the area around Mediamatic (Amsterdam).