My First Murder. A Short Story by Martin Michael Driessen

Former opera and theater director Martin Michael Driessen (b. 1954) is an acclaimed writer. His novels Rivers and The Pelican were translated into English by Jonathan Reeder. The American-born Reeder, based in Amsterdam, also translated Driessen’s story My First Murder from the collection of short stories of the same name. You can read it here for the first time in English, with an introduction by Reeder himself.

The Dutch newspaper Trouw

reviewed Martin Michael Driessen’s recent collection of stories, Mijn eerste moord, with the words: ‘Driessen is an outstanding storyteller. It’s clear in everything [he writes] that Driessen is also an opera and theater director: his prose is tautly staged and has a clear plot. […] He knows exactly what he is doing and where he wants to go.’

Driessen’s delightful short story My First Murder is precisely such a piece of writing. He lets the reader know right off the bat what kind of narrator we are listening to and the kind of absurd reasoning we can expect in the next couple of pages. And, as in his novels Rivers and The Pelican, he has a plot twist in store that turns the notion of justice, fair play, and a ‘proper’ ending on its head.

Translating this gem was both a challenge and a treat. Challenging because the narrator, while some years older at the time of the telling, is still in many ways a child; a treat because it is laced with Driessen’s typical black humor, and because he is indeed an imaginative storyteller who can devise a ‘killer’ plot.

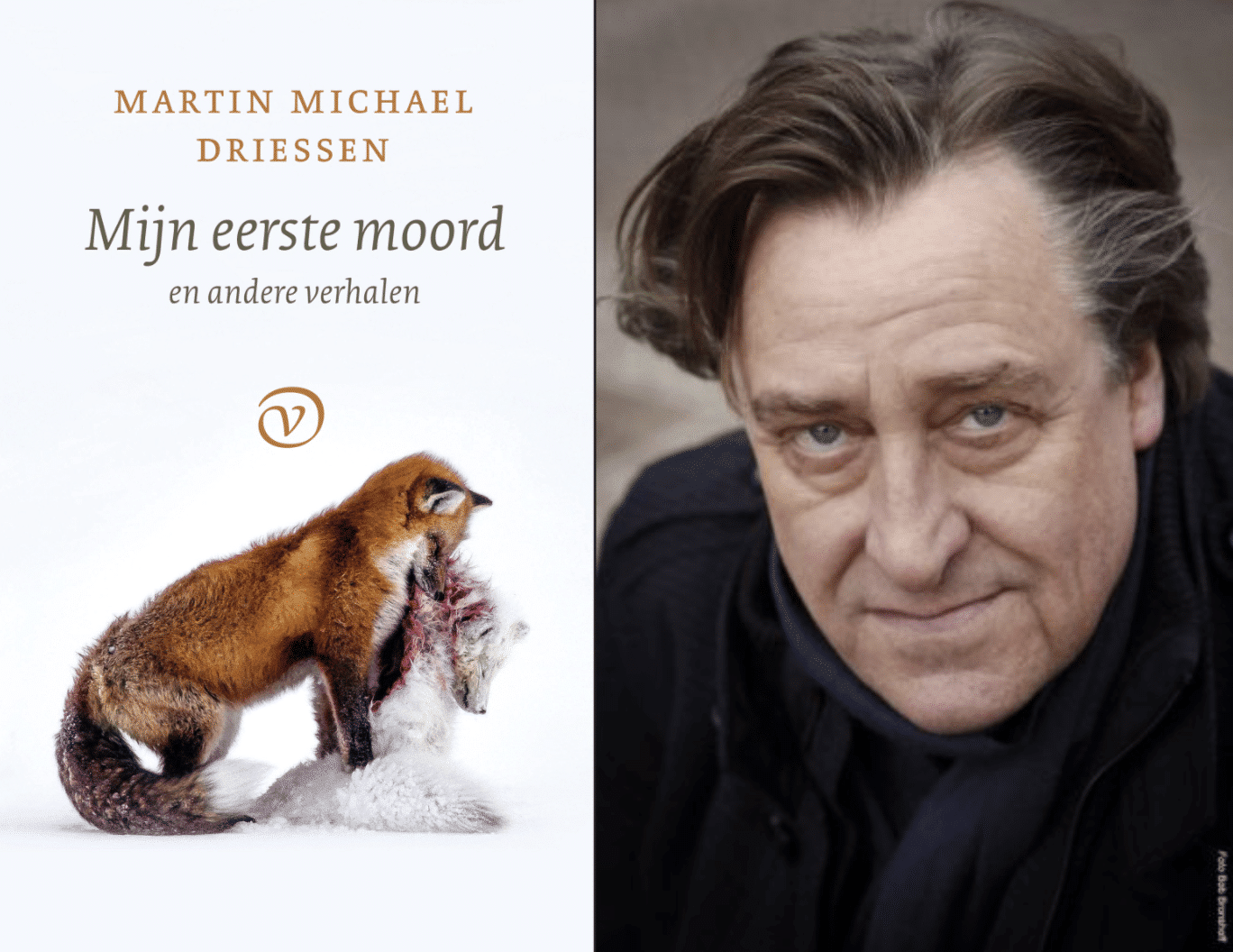

Martin Michael Driessen

Martin Michael Driessen© Bob Bronshoff

My First Murder

I was in kindergarten when that thing with Joey happened, that’s how I know we were still living in Bloemendaal. There was one of those power sheds and beyond it was a narrow canal, and across from that were the train tracks, where the train rode that my father took home from his job in Breda, and sometimes I was allowed to meet him at the station.

Joey and I used to play down by the canal, even though we weren’t supposed to, but it was a dumb canal anyway, ’cause there were no sticklebacks. I thought Joey was pretty stupid, but he was my only friend. One time we were sitting behind the power shed, it was made out of a kind of concrete with shells in it, and we could never get the door open. The door was steel and painted green, and was at the front. We watched the Haarlem train pass and I said, I wonder if you could get a train like that to jump the rails. Joey reckoned we’d need his father to help, and decided it wasn’t such a good idea after all because then the train might fall onto their house and his bedroom was at the back. It wasn’t even his real father anyway, it was a stepfather. They did have a dog, though, Bonito. A lot of dogs have better names than kids do.

Joey started throwing clods of dirt into the canal, to make holes in the duckweed. But there weren’t any ducks, they were all further up in the pond in the park. It was a dud canal, actually. After a while he said, I’m gonna go get a stick to poke around with, you want to, too? I didn’t feel like it. We can push the lily pads underwater, he said. I thought that was a dumb idea, so I just stayed put.

Another train passed, going the other way. Joey waved but I didn’t, because no way was my father in it, he was still in Breda. Joey was wearing weird gray woolen shorts. There was a lot about him that was weird, this was because his mother came from Germany. He also had a really weird school bag that you had to carry on your back. It was German, too.

Anyway, what happened was: at a certain point I was standing behind Joey and all of a sudden I figured it would be better if he was just gone. So I gave him a shove. A really hard one. He fell in, but not face-first like I’d expected; he twisted as he fell and looked really surprised. That was the only time anyone had looked at me surprised while they’re falling over. He landed with a smack, the duckweed heaved in all directions, and by the time it settled back into the middle I was clambering back up to the power shed, because I wasn’t sure what to do next. Lucky thing that train had already passed, just imagine if somebody had seen me and called the police.

But when I turned and looked, I didn’t see anything, so I went back down. It took a minute, but Joey’s face poked up through the duckweed. That wasn’t the plan, so I took the stick he’d used to dunk the lily pads and pushed him back underwater. After a while he came back up again, and I pushed him back under until he stopped bubbling. Then I had to wait while another train passed. After that he didn’t do anything at all, his face had gone all white, but he didn’t seem to mind. Fine by me. I got my scooter, ’cause we were on the scooters, and rode home. It was just a short way but I took my time because I had to think things through. Only at the very end I sped up and shouted, ‘Mama! Mama! Joey fell into the canal!’

The effect was huge. Mothers came rushing out from all sides and ran down Elm Street towards the power shed, some of them still wearing their aprons. I coasted calmly after them. Three mothers were standing in the canal, and they dragged Joey out of the water. I parked my scooter next to Joey’s. The mothers all screamed, and mine held him upside down by his ankles and a whole lot of green water came out of him, it was a real fuss.

A few days later I got a big box of milk chocolates from his parents, because I had saved his life. Later, Joey said I had pushed him in, but of course no one believed him.