New Biography Sketches Portrait of ‘Maverick’ Erasmus as a Tragic Optimist

The Erasmus that Sandra Langereis sketches in her biography feels pleasantly familiar: a man with great ambition, who took full advantage of the technical innovations of his time, and who took orders from no one. But his success also had its drawbacks.

A biographer who wants to portray a figure from a more distant past has a challenging task ahead of them. People from a different age lived, according to the famous opening sentence of L.P. Hartley’s novel The Go-Between, in a foreign country. They did things differently from us, thought and wrote in an idiom that is not akin to our own. This is the case a fortiori

for Erasmus (1466-1536). Although he came from Rotterdam, grew up in the Netherlands, and later returned regularly to these regions, he did not write a single word in Dutch.

Erasmus was already famous in his own lifetime. Constantly looking for new patrons to provide him with an income, and a printer and publisher who could meet his high expectations, he moved from city to city throughout Europe. Erasmus’ oeuvre is extensive: to this day scores of influential thinkers and administrators invoke his work but his ways of thinking is largely lost to us five centuries later.

Sandra Langereis

Sandra LangereisⒸ Geert Snoeijer

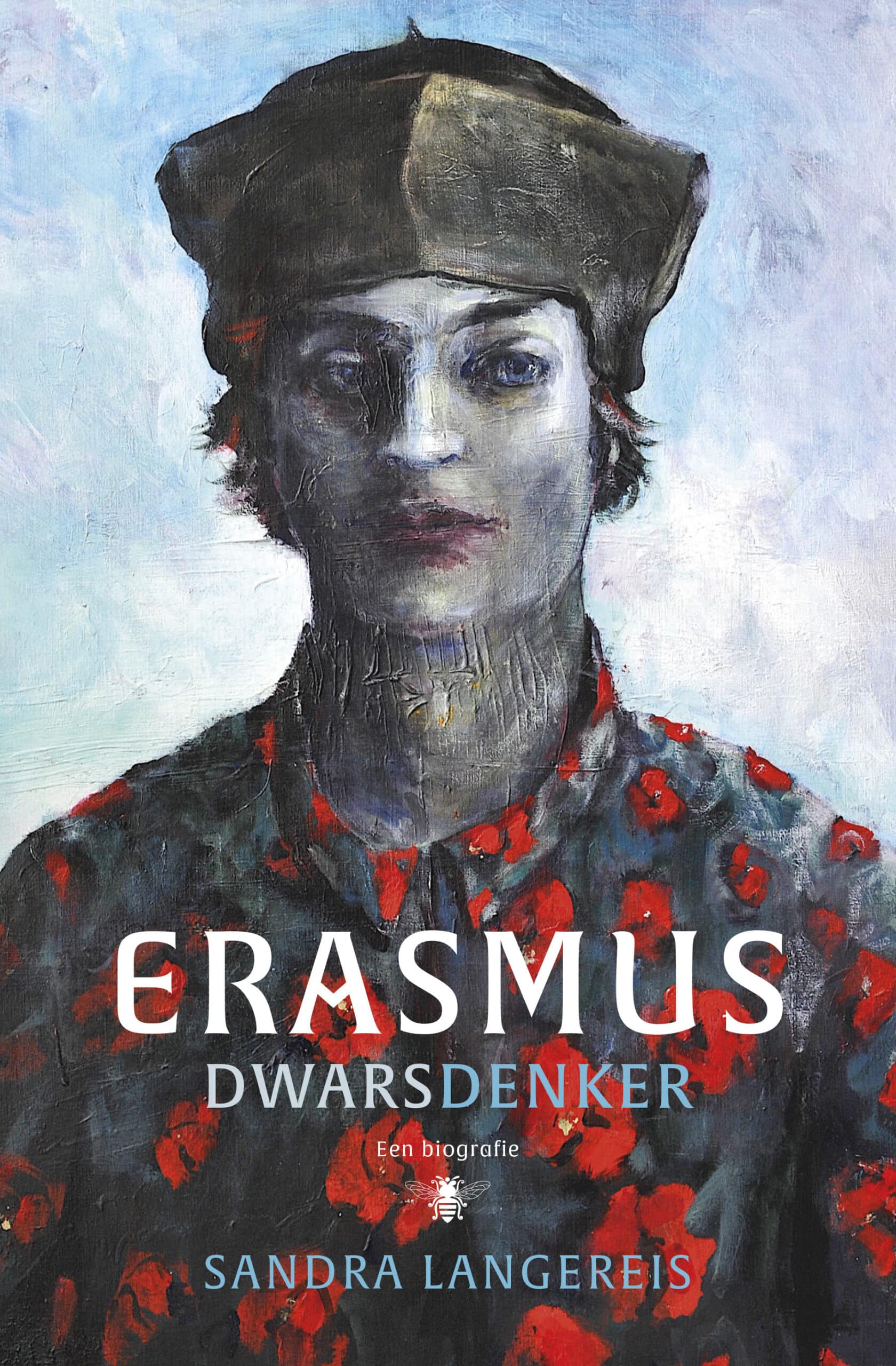

Of course, Sandra Langereis is aware of the distance that separates us from Erasmus. It is exactly for this reason that she chooses explicitly to bring the hero of her biography closer to the reader. A young Erasmus graces the cover in a shirt adorned with poppies, just as he was painted by Neel Korteweg, looking as though he were a modern-day hipster. At times this intervention results in speculative insights, at others they are more surprising. Langereis suggests, for example, that Erasmus believed in the principle of male love and labels him the ‘forefather of Dutch cabaret’ following an analysis of his In Praise of Folly with reference to the radical lyrics of the duo Freek de Jonge and Bram Vermeulen, who worked together under the name Dutch Hope in Dark Times.

The consistently playful, and at times even jocular, tone that accompanies such perspectives does not detract from the seriousness of Sandra Langereis’ work. At the end of her detailed prologue, in which she recounts that if not Erasmus’ fame then at least his likeness had reached already as far as Japan by the early seventeenth century, she leads her hero centre stage and, with reference to Ezra Pound and Harry Mulisch, has him proclaim: “End Fiction. Try fact!”

It becomes possible to imagine how profound the knowledge revolution instigated by Erasmus was. According to Langereis, this was his greatest achievement

In the following six hundred and fifty densely printed pages, Langereis disseminates frequently unknown facts in great detail, providing an abundance of context. It is one of the great charms of this book. In light of this, it becomes possible to imagine how profound the knowledge revolution instigated by Erasmus was. According to Langereis, this was also his greatest achievement.

Erasmus, who was the son of a student who had died relatively young while studying in Italy and working as a copyist and a student priest, soon foresaw the opportunities presented by the printing press. Henceforth, numerous people living at a great distance from one another would be able to access texts, and therefore also knowledge, and discuss these with each other through their letters. For an ambitious scholar, this development presented excellent opportunities, provided that he found an internationally operating publisher willing to print his works. It is therefore only right that Langereis pays ample attention in her work to the relationships between Erasmus and his publishers.

In Venice, he lodged for some seasons with the famous Aldus Manutius. Fleeing from the Ottoman advance, numerous Byzantine scholars had settled near the lagoon. The Greek manuscripts they had brought with them, first put into print by Manutius and his colleagues, caused a great sensation. Suddenly, an entirely new antiquity surfaced: the springs that Cicero and all those other Roman authors had tapped into and that had remained unknown for centuries.

Desiderius Erasmus receives the Book of Truth by Jacobus Baptist

Desiderius Erasmus receives the Book of Truth by Jacobus BaptistⒸ Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

This revelation led Erasmus to focus on the Greek basic text of the Bible. Following in the footsteps of Lorenzo Valla and other Italian humanists, he had become convinced that careful study of those earlier Greek texts would yield a better Latin translation than the Vulgate, which had been badly corrupted over the centuries. In this way, a believer would be able to appropriate the original Christian teachings in order to become a better person.

Erasmus provided this “improved” Latin text of the New testament based on various Greek manuscripts in his Novum Instrumentum of 1516. Printed in Basel by the publishing house Froben, this work soon found its way to libraries and scholars throughout Europe and had enormous impact. During the remaining twenty years of his life, Erasmus would publish four more versions, invariably updated, under the even more ambitious title Novum Testamentum.

Erasmus believed in a dialogue with his readers. Each time they presented him with a previously unknown manuscript with original Greek texts there arose a new opportunity, by means of comparison between all those different manuscripts, to reconstruct a version of the Scripture that was as uncorrupted as possible.

no matter how hard Erasmus and his supporters studied, no irrevocable truth emerged from their toil. It only led to gloom

Erasmus was in essence an optimist. In his view, sustained study and debate would ultimately lead the benevolent being back to the divine truth that had disappeared from view during fifteen hundred years of Christianity. But contained in this voluntarism was also Erasmus’ greatest tragedy: no matter how hard he and his supporters studied or how passionately they disagreed with each other, shifting commas and suggesting new nuances of the text, no irrevocable truth emerged from their toil. On the contrary, it led only to gloom.

This was compounded by the split in Western Christendom following Luther’s bold indictment of the papal indulgences trade of 1517. In both camps the doctrinaires who believed the immutable truth was given by God quickly took over. In fierce terms, and with a heavy hand, they turned against Erasmus and his kindred spirits. But, unlike his “arch friend” Thomas More, who would eventually be executed by Henry VIII for resisting his top-down church reform, Erasmus had no talent for martyrdom.

Unlike his 'arch friend' Thomas More, Erasmus had no talent for martyrdom

Supported by his now permanent publisher Froben, the aging and isolated Erasmus withdrew to Basel and later also briefly to the nearby Catholic city of Freiburg im Breisgau. There he taught young admirers, who lived with him for a fee, the intricacies of humanism and maintained his correspondence with a circle of friends and colleagues scattered all over Europe. At sixty-six, an advanced age for that time, he died in bed.

In the past century, two important Erasmus biographies have appeared in Dutch. Johan Huizinga, who published his account in 1924, was stern in his view of the half-grown chamberlain. The socially engaged cultural historian accused Erasmus of wavering between the old church and the Reformation and never coming to a real decision. In 1986, the Reformed church historian Cornelis Augustijn recognised that Erasmus was, above all, a pioneer of ecumenism.

Such preoccupations are, like for most of us, quite foreign to Sandra Langereis. Christianity is no longer the self-evident frame of reference within which all our comings and goings take place. We miss, above all, Erasmus’ familiarity with the ancients: sometimes they still inspire us but the idea that, after centuries of “darkness”, we might finally measure ourselves against their ideas, seems ridiculous to us. We no longer speak their languages and, even if a few still read them, they do so with much difficulty.

Langereis’ Erasmus, on the other hand, feels pleasantly familiar. Marked by the absence of a safe haven and burdened with incredible ambition, Langereis’ literary godchild set out early on in life in search of social success. In doing so, he took full advantage of the possibilities presented to him by the fledgling technique of printing with loose lead type. But his eventual success came at a high price: Erasmus set the bar high for friendship and his impudence frequently put off potential lenders. Langereis’ Erasmus is his own master and nobody’s servant. It is an appealing and contemporary story and Sandra Langereis tells it beautifully.