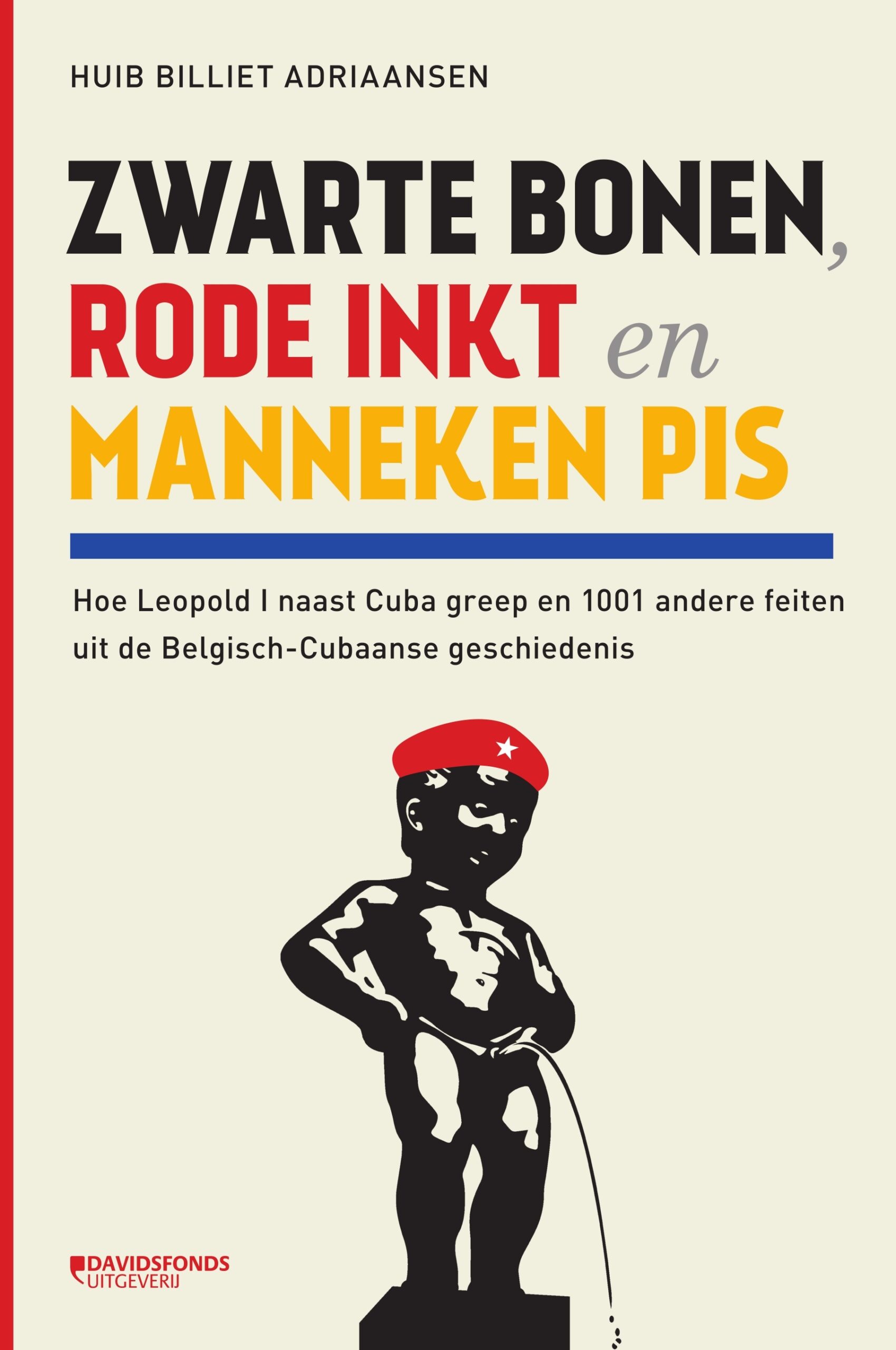

Our Man in Havana and Other Facts about the Belgo-Cuban Connection

Had it been up to King Leopold I, Cuba would have been a Belgian colony. There is, after all, a Manneken Pis in Havana. And both the Cuban revolutionaries and the government troops fought with machine guns stamped made in Belgium. You can read about these facts – and much more – in an exciting book about the shared history of Cuba and Belgium since the early sixteenth century.

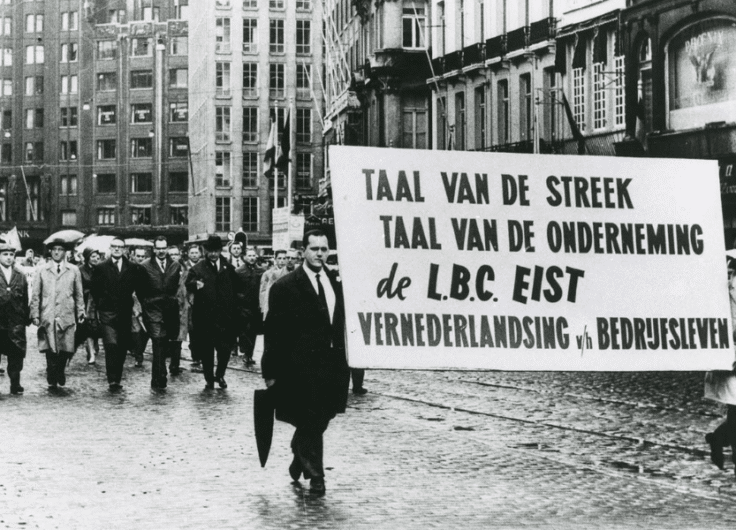

Map of Cuba from the Mercator Hondius 'Atlas Minor'

Map of Cuba from the Mercator Hondius 'Atlas Minor'Cuba. Off the top of my head, and with no recourse to Google, I think of sugar, cigars, beards & uniforms, the Bay of Pigs, Our Man in Havana, free health care and Cuba Libre. My first impressions may have been somewhat limited but, thanks to Huib Billiet Adriaansen’s book Zwarte bonen, rode ink ten Manneken Pis (Black Beans, Red Ink and Little Peeing Boy) I’ve recently gained many more. That’s the added value of reading ‘1001 facts from Belgian-Cuban history’, as the subtitle of the book suggests. Adriaansen has incorporated five hundred years of history into a series of chronologically ordered “press releases”.

It all starts on the Garenmarkt in Bruges. There stands the Court of Cuba, where Jan de Witte lived, the man who was allowed to call himself Episcopus Cubansis for a while. In 1517 the young king Carlos I appointed this wealthy and nobleman of Bruges as the first Bishop of Cuba. De Witte never set foot in Cuba but from the old continent, he turned his mind to the job, appointing an archdeacon, a teacher, choristers and a treasurer for his overseas diocese. The cathedral that was eventually built was not much more than a wooden shack at that time, but the newly appointed prelate nevertheless provided a guard to keep the street dogs out of God’s house.

Later reports confirm that soldiers from the Low Countries, along with craftsmen, merchants, aristocrats, spies and even drummers were sent to Cuba.

Havana on a coloured print from an edition of the book 'De nieuwe en Onbekende Wereld of Beschryving van America en 't Zuid-land by Arnoldus Montanus'.

Havana on a coloured print from an edition of the book 'De nieuwe en Onbekende Wereld of Beschryving van America en 't Zuid-land by Arnoldus Montanus'.The second chapter starts with Belgian independence. In 1831, the ship Jean Key was the first to sail into Havana’s harbour under the Belgian flag, much to the dismay of the Dutch sea captains who were already there. A few years later, the first Belgian consul arrived. Diplomatic and mercantile ties were cemented. Belgian bricks, textiles and oil were exported to Cuba; cane sugar and tobacco were imported to Belgium.

But King Leopold I wanted more: he had developed a taste for colonialism and wanted to buy Cuba. His Minister Plenipotentiary in London informed Lord Henry Palmerston of this proposal, but the English Foreign Minister believed that Belgium – still a very young country – did not yet have enough hair on its chest to father an adopted child, especially not the ‘strapping, strong and stubborn scion of another parent.’ As a result, Cuba remained in Spanish hands well into the nineteenth century.

José Marti: 'Cuba and Belgium are both countries of modest size, surrounded by large, powerful and often hostile powers.'

This brings us to the Cuban freedom fight that, after 1868, led to a sequence of three wars. It was during this time that the journalist José Martí became a folk hero. He was the one who pointed out the similarities between Cuba and Belgium: they were both countries of modest size, surrounded by large, powerful and often hostile powers. Additionally, Belgium’s political stability, liberal constitution and established neutrality appealed to the political imaginings of Cuban academics, students and aspiring reformers.

Bronze soldier holding a Belgian rifle, at the Pantheon of the Revolutionary Armed Forces at Colón Cemetery in Havana.

Bronze soldier holding a Belgian rifle, at the Pantheon of the Revolutionary Armed Forces at Colón Cemetery in Havana.Belgium honoured its neutrality by supplying weapons to both the Spanish troops and the insurgents. In the latter case, some care was taken for the sake of discretion when, in 1869, the revolutionaries received a number of machine guns from Liège labelled as “meat mincers” – oh the vagaries of waybill descriptions!

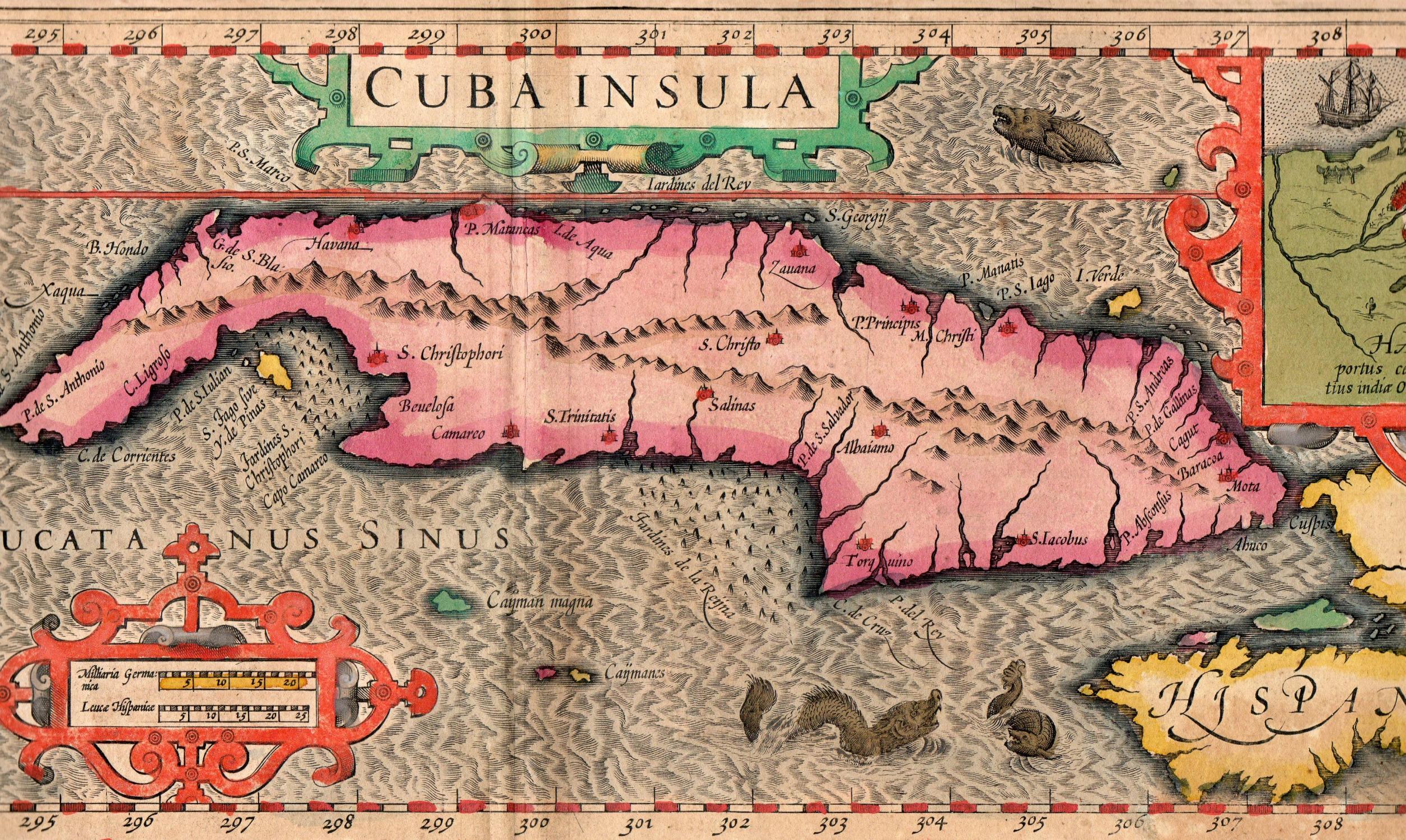

By 1902 Leopold II was one of the heads of state who wrote to congratulate the new “Cuban Republic” (read: American protectorate), which it remained until 1934. However, it wasn’t all peace and quiet and pats on the back. A few years later, Leopold II’s royal note was repudiated. The newspaper Cuba y América ran a strident campaign against his policies in the Congo. Eventually, after some diplomatic efforts, all the ruffled feathers were smoothed.

Letter from the Belgian King Leopold II congratulating Tomás Estrada Palma, the first President of the Republic of Cuba, 24 June 1902.

Letter from the Belgian King Leopold II congratulating Tomás Estrada Palma, the first President of the Republic of Cuba, 24 June 1902.Adriaansen continues with some less controversial stories about Belgian racing pigeons that will take all the prizes in Cuba and about Maurice Des Ombiaux’s Petit Traité du Havana (Small Treatise on Havana, 1913), in which the prolific writer from Namur praised the Cuban cigar as the best remedy for an unhappy love life. Cuban publications cited his advice, although his particular suggestion to smoke Havanas in autumn, when the delicious aromas of tobacco blended with the scent of dead leaves, was not particularly relevant in the subtropical climate.

Manneken Pis, found in the Santo Suárez district of Havana.

Manneken Pis, found in the Santo Suárez district of Havana.© Anne-Marie Helon

In the period between the anti-imperialist congress at the Egmont palace (1927) and the World Expo in Brussels (1958) the lazos de amistad – bonds of friendship – were regularly mentioned. Textiles and sugar continued to be traded, and in Flanders, we began to see the first cafes and cabarets with the words Cuba or Cuban in their names. Author Karel Jonckheere (1906-1993) visited the island and wrote his travel stories Cargo and Tierra Caliente, in which he confides that his blonde hair, which made him the ‘biggest ugly person in Western Europe’ was a big hit with the Cuban ladies. Copies of the Manneken Pis (Little Peeing Boy) appeared in Havana and Camagüey, and Leopold III visited a Cuban cigar factory, a few schools and a maternity hospital.

The final two paragraphs of the book illustrate the somewhat awkward dance between post-revolutionary Cuba and Belgium which, according to the author, ‘stubbornly continues to play the consensus builder card.’ It was an era of arms transfers and diplomatic incidents, but also – especially after the 1990s – of increasingly intense cultural and economic cooperation. During his visit to Cuba in 1968, the famous Belgian author Hugo Claus called the revolution ‘a concrete fact’ and Fidel Castro ‘a clever statesman’ – and this despite having been pelted with stones by children on a previous visit because of his rather American-looking clothing.

Cartoonist GAL's drawing on the occasion of Louis Michel's motorbike ride in Havana in 2001.

Cartoonist GAL's drawing on the occasion of Louis Michel's motorbike ride in Havana in 2001.© GAL

In 2001, Belgian Secretary of State Louis Michel chugged along Havana’s seawall on a vintage motorcycle. During the Belgian Presidency of the European Council, Michel hoped to strengthen ties with Cuba and stimulate political dialogue. He made a positive impression, even if he himself was a bit disappointed by the rigid position of Fidel and Co. towards the rest of the world.

However, Belgian singer Lou Deprijck (Two Man Sound, Lou & The Hollywood Bananas) had no complaints. After one mojito too many, he tumbled off a balcony and, several open leg fractures later, became acquainted with Cuban health care: the nurses were gorgeous, and patients were allowed to smoke cigars in bed!

Front page of the Cuban newspaper La Lucha on the occasion of the Belgian national holiday in Cuba, 21 July, 1918.

Front page of the Cuban newspaper La Lucha on the occasion of the Belgian national holiday in Cuba, 21 July, 1918.Not every ‘news clipping in Adriaansens book is this kind of jolly anecdote. Some are rooted in historical significance, such as the stories about brave acts of war committed by some locals under the “Rey Caballero” Albert I as an expression of Cuban Belgophilia.

Streets (and even one café) are called Bélgica, the 21st of July is suggested as the National Day, and during the war, the wife of President Mario García Menocal created a Belgian support committee.

But there are also parts of the book that remain a bit reductionist and pointless. That is not a reproach to the author. Cuban-Belgian relations is the string on which he has to place both shiny pearls and slightly duller pebbles. And all in all, that results in a lovely jewel.

Huib Billiet Adriaansen, Zwarte bonen, rode inkt en Manneken Pis. Hoe Leopold I naast Cuba greep en 1001 andere feiten uit de Belgisch-Cubaanse geschiedenis, Davidsfonds, Antwerpen, 2020, 240 pp.