Pink Triangles: Adopted Memories of Gay Persecution in Nazi Europe

For a long time, the persecution of gay men and women during the Second World War went unrecognised. Meanwhile, the pink triangle became a universal symbol of the havoc caused by homophobia. At Kazerne Dossin in Mechelen, an exhibition highlights the precarious situation of gays and lesbians in Nazi Germany and the occupied countries of France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

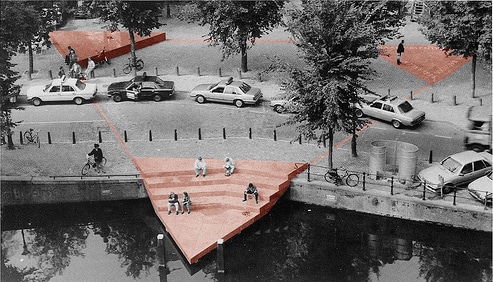

Since 2007, in Verviers, Belgium, a plaque has commemorated the gay and lesbian victims of the Nazi regime. More than 10,000 of them were deported; 6,000 men and women never returned. Twenty years prior, the Homomonument was erected in Amsterdam, commemorating those same victims. The pink triangle – a symbol used by the Nazis in some concentration camps to identify homosexuals – figures prominently in both memorials. No Belgian or Dutch, however, was pinned a pink triangle during the Nazi era.

Between optimism and oppression

The exhibition Homosexuals and Lesbians in Nazi Europe, on view until December 2023 at Kazerne Dossin in Mechelen, demonstrates that those wanting to understand pink triangles must look back to the 1920s. The shock of Nazi persecution was all the greater after the optimism of the early twentieth century. The first gay associations emerged in Germany and the Netherlands. They published their own magazines, which were openly available at newsstands.

In Germany, a broad consensus grew that Paragraph 175 of the penal code (the section that criminalised homosexual acts) was ready to be ditched. In France and Belgium, where homosexuality was not prohibited, activism remained more limited. But also there, gay life flourished in major cities. Bars and clubs for gays and lesbians, such as Eldorado in Berlin or Magic City in Paris, were immortalised in art and literature.

Exterior view of the Eldorado club, Berlin, 1932

Exterior view of the Eldorado club, Berlin, 1932© Collection Bundesarchiv Bild

The optimism and glamour of the 1920s should not obscure the fact that this was also a time of oppression, despair and fear. In Germany, not only did the infamous Paragraph 175 allow prison sentences for male homosexual acts, but the aversion towards homosexuality also regularly led to extortion and suicide.

In the Netherlands, Article 248bis of the penal code criminalised gay and lesbian contacts between people above and under the age of 21. The idea behind that law was that homosexuality mainly arose because adult men had seduced malleable youths. Moreover, in Germany, the Netherlands, France and Belgium, the laws on public indecency could be used to prosecute homosexual contacts. In each of these countries, the police organised sporadic raids in gay bars.

Decadent gay culture

During the rise of the Nazis at the end of the 1920s, Magnus Hirschfeld became the ultimate symbol of what they perceived as a decadent and derailed gay culture. Hirschfeld was Jewish and gay, director of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaften in Berlijn, and an authority on sexology. He propagated the idea that homosexuality was innate, but not a disease. In 1930, Hirschfeld noticed the increasingly hostile climate and left Germany. Three years later, students with Nazi sympathies ransacked his institute. The extensive library went up in flames.

Costumed party at the Hirschfeld Institute of Sexology, Berlin, 1920

Costumed party at the Hirschfeld Institute of Sexology, Berlin, 1920© Magnus Hirschfeld Gesellschaft e.V., Berlin

Not all gays were as forward-thinking as Hirschfeld. Initially, some admired the cult of masculinity and aesthetics of virility of National Socialism. Ernst Röhm had no problem reconciling his homosexuality with his position as head of the Sturmabteilung. After Röhm was eliminated during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934, little doubt remained about the view of the Nazis towards homosexuality. In 1935, the Nazis tightened Paragraph 175: Thereafter, any sign of desire between men, even kissing, was punishable by up to ten years of forced labour. Surveillance tightened and informants were given free reign. The famous Eldorado closed its doors, and the building became home to Nazi headquarters.

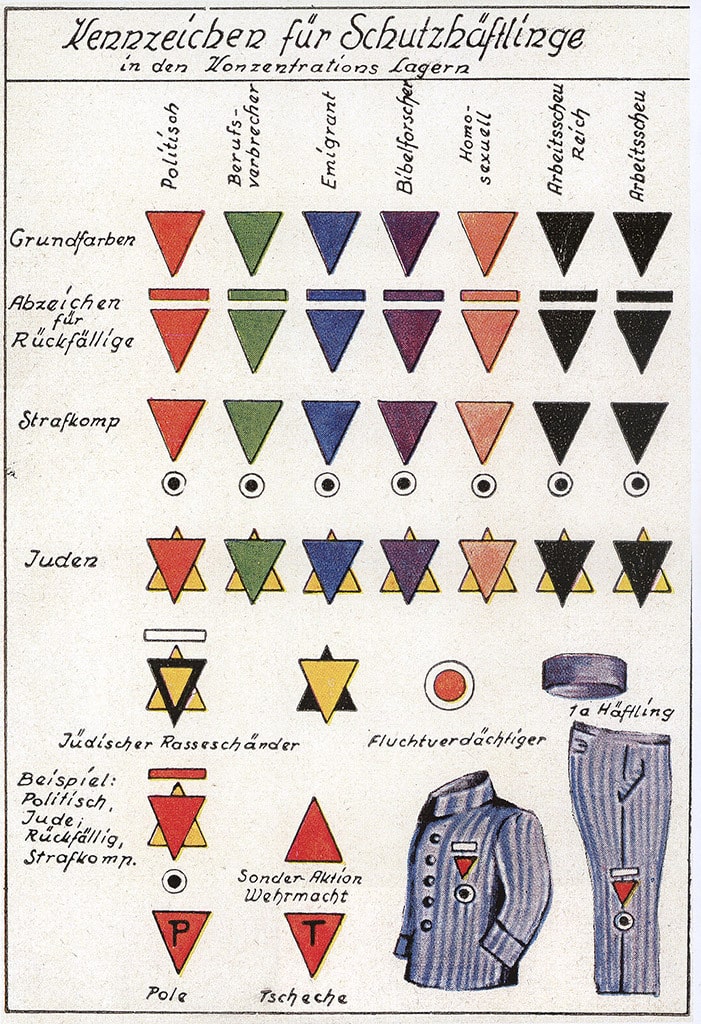

In Nazi Germany, courts sentenced an estimated 50,000 men for homosexual acts, mostly to prison. Approximately 10,000 of them ended up in concentration camps after their sentence. It is estimated that roughly 6,000 of these men perished there. Unlike for Jews, there was no comprehensive plan to annihilate gays. At some concentration camps, though not everywhere, gays were identified with a pink triangle. Some of them were also castrated, and on a number of gay men, doctors performed medical experiments that were supposed to lead to their ‘cure’. Not only deliberate murder, but also suffering led to their life’s end.

Although the memorial plaque in Verviers suggests otherwise, the Nazis perceived lesbians as less of a serious threat to the German race. They did not persecute them for their sexuality.

In 1933, the famous Eldorado closed its doors, and the building became home to Nazi headquarters.

In 1933, the famous Eldorado closed its doors, and the building became home to Nazi headquarters.© Collection Landesarchiv, Berlin

Ten years in prison

The persecution of gays was primarily a concern in Germany. Unlike the persecution of the Jews, the Nazis did not systematically persecute gays in the German-occupied territories. Shortly after the occupation had begun in the Netherlands in 1940, the Nazi regime enacted Regulation 81/40, a law modelled on Paragraph 175. The regulation made sex between men punishable by up to ten years in prison. This came next to the already existing Article 248bis, which determined the higher age of consent for homosexual contacts. However, the Nazis left the actual search and prosecution of gays to the Dutch police. As before the occupation, they did not make this a priority.

Altogether, several hundred gay men in the Netherlands came in contact with the justice system during the occupation. That was in line with the number before the occupation; the number of convictions may have even decreased. Most of those convicted were imprisoned.

In Belgium as well, the occupation did not lead to major changes in this area. Homosexual relations were not punishable before the war or during the occupation. When the German military court prosecuted a resident of Brussels in 1942 for forgery and fraud, they did not condemn him for the homosexual acts he had confessed to.

The court-martial ruled that homosexual acts between adults in Belgium could not be prosecuted. The only ones who were sometimes targeted by the Nazis because of their homosexuality were German soldiers and Belgians in the German service. As far as is known, nine of them were convicted under Paragraph 175.

Gays and lesbians who were targeted by the Nazis for being Jewish or supporting the resistance often received harsher treatment

The limited prosecutions for homosexuality in the Netherlands and Belgium did not mean, of course, that gays were unaffected by the occupation. Gays and lesbians who were targeted by the Nazis for other reasons – such as being Jewish or supporting the resistance – often received harsher treatment. Like other citizens, they had to live with arbitrariness, hardship, food shortages and curfews.

Especially in the Netherlands, many gay bars closed during the occupation. In Belgium, however, many remained open. At the exhibition, we hear the testimony of the Brussels lesbian Suzanne De Pues, who later founded the first Belgian gay movement. Sometimes, a German soldier would stop by a gay bar, have a beer and leave. Other documents also show that the German occupier closely watched Belgian gay bars – mainly to prevent German soldiers from frequenting them – but did not intervene.

Despite the hardship and fear, the occupation sometimes offered new homoerotic possibilities. In her dissertation on homosexuality in the occupied Netherlands, for example, Anna Tijsseling cites the account of gay actor Jaap Hoogstra. The implementation of a ‘Sperrzeit’(curfew) meant that people were no longer allowed to go out after 9 or 10 pm. Whoever was elsewhere at that time, had to spend the night there. This gave rise to a new term in the gay scene: the term ‘Sperrzeit’ became ‘sperm time’.

Harsh repression after the liberation

Ironically, in large parts of Europe, the liberation did not mean ‘liberation’ at all for gays. On the contrary, in the Netherlands and Belgium, the postwar period led to harsh repression. This is a subject largely overlooked by the Dossin exhibition. Regulation 81/40 may have disappeared in the Netherlands after the war, but the number of convictions of gays reached a peak in 1949 due to more frequent appeals to Article 248bis.

In Belgium, things remained quiet for a while, but in the 1950s the police also started taking much stronger action against homosexuality. This eventually resulted in a new penal code in 1965, Article 372bis, which, as in neighbouring countries, set the age of sexual consent higher for homosexuals than for heterosexuals.

In the late 1950s, In West Germany alone, courts convicted more men than in all of Germany during the war years

Even in Germany, the situation for gays hardly improved after the end of the Nazi regime. Paragraph 175 persisted after the war. The German Democratic Republic soon reintroduced the less far-reaching pre-Nazi version, but in West Germany, the Nazi regulation remained in force until 1969. Some men convicted under Paragraph 175 had to continue serving their sentences after the liberation. After 1945, the persecution of gays may not have reached the same proportions as during its peak in the late 1930s, but in West Germany alone, courts convicted more men under Paragraph 175 in the late 1950s than in all of Germany during the war years. Moreover, once convicted, it was often difficult to find a good job.

The pink triangle as a symbol

Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that gays who had been persecuted under the Nazi regime did not immediately speak up after the war. This only changed after the 1970s under the influence of a new generation of gay activists. In fact, gay movements had discovered that, politically, the story of victimisation was very interesting. Though the pink triangle was all but forgotten in the 1950s and 60s, it returned in the 1970s.

Nazi concentration camp badges

Nazi concentration camp badges© Wikimedia Commons

In 1972, under the pseudonym Heinz Heger, the Austrian Josef Kohout wrote about his experience as a gay man at Camp Dachau: Die Männer mit dem rosa Winkel (The Men with the Pink Triangle). His memoirs ensured that a wide audience became acquainted with the persecution of gays by the Nazis, and with the pink triangle. That image became even more popular thanks to the play Bent (1979) and later a film (1997) by the American gay and Jewish author, Martin Sherman, inspired by Kohout’s story. For gay movements, the pink triangle became a means of demanding political reform. They were unacknowledged victims of the Nazi horrors.

In the 1970s, gay activists did not shy away from bold claims. The Nazis are said to have killed 200,000, 300,000, or even three million gays in concentration camps. Where was the recognition? The compensation? Radical gay movements used the pink triangle as a provocative symbol of pride. Especially in the US – where the symbol was actually completely unknown – the pink triangle became a strong political image.

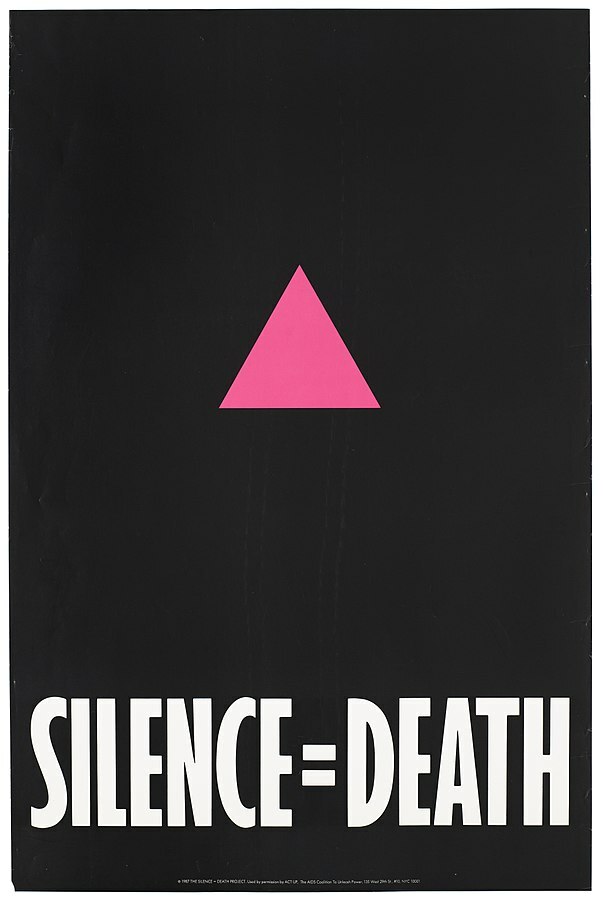

The poster ‘Silence = Death’ equated the negligence of the American government during the AIDS epidemic with the persecution under Nazism, USA, 1986

The poster ‘Silence = Death’ equated the negligence of the American government during the AIDS epidemic with the persecution under Nazism, USA, 1986© Wellcome Library no. 669136i

The horrors of the Nazi persecution became what we could refer to as an ‘adopted’ memory. Though they had taken place elsewhere, the events became part of the collective memory. Using the image of the pink triangle, the poster ‘Silence = Death’ equated the negligence of the government during the AIDS epidemic with the persecution under Nazism.

The pink triangle lost some of its specific context and became a broader symbol of victimisation. Perhaps partly through activism in the US, the pink triangle re-emerged as a symbol in Western Europe. The fact that the memorials in Amsterdam and Verviers use the symbol fits in perfectly with that perspective. Belgium and the Netherlands adopted the memory of the gay persecution by the Nazis – even though it had not taken place in their own country.

There is little doubt that the pink triangle and the narrative of Nazi persecution led to political success. But it also came with risks. The real history of discrimination and persecution of the LGBTQ+ community is partly externalised: it is all the fault of the Nazis. Belgians and Dutch are not to blame. Moreover, the obscene violence of the concentration camps dwarfs other forms of discrimination. So what does the queer community have to complain about today?

Additionally, the pink triangle and Nazi violence inevitably place the focus on the suffering of white gay men. They emerge as the ultimate victims, to the detriment of lesbians, trans people and queer people of colour. The other forms of oppression that they often had to deal with and continue to experience get lost in the margins.

Designed by Amsterdam-born artist Karin Daan in 1979, Amsterdam’s Homomonument was the world’s first major monument commemorating gay and lesbian victims of the Third Reich.

Designed by Amsterdam-born artist Karin Daan in 1979, Amsterdam’s Homomonument was the world’s first major monument commemorating gay and lesbian victims of the Third Reich.Homophobia today

The exhibition at Kazerne Dossin treads a fine line between emphasising the suffering that gays and lesbians endured and nuancing myths of victimisation. The exhibition shows regulations and figures, police reports and memoirs, interviews and photos. The stories of dozens of gays and lesbians who lived during the Nazi era (from Germany, Austria, France, the Netherlands and Belgium) are nuanced and diverse. They show joy and sorrow, resistance and betrayal.

At the same time, some promotional texts particularly emphasise victimhood: the fate of gays and lesbians has been ‘unrecognised for a long time’; the exhibition sheds light on their ‘precarious situation’. Ultimately, the exhibition makers want to warn about the consequences of homophobia and queerphobia today. Therefore, the pink triangle may still remain relevant after all. An adopted memory, with all its flaws, can also be a powerful symbol.