The Sodom of the North. Homosexuals Were Burned at the Stake in Medieval Bruges

Belgium is one of the most tolerant countries when it comes to LGBTQ rights. But it hasn’t always been that way. Nowhere in Western Europe were homosexual men persecuted as much as in Bruges in the late Middle Ages. Research by historian Jonas Roelens shows that the economic crisis, the need for scapegoats and prejudices against foreigners may have played a role in this.

Bruges, 26 January 1558. Two boys, 19-year-old François van Daele and the just 14-year-old Willem de Clerck, were sent to the scaffold. Despite their youth, both were given very heavy sentences. François and Willem were to be flogged until bleeding with rods, and then their hair would be burned off with a glowing hot iron. After these gruelling tortures, the boys were banned from Flanders. Their punishment? They had had ‘unnatural sex’ with a priest. This shocking case offers an intriguing insight into the prosecution of deviant sexuality in the Southern Netherlands, and the importance of social capital in sentencing.

Bruges monks at the stake in 1578

Bruges monks at the stake in 1578© City Archives of Bruges, Collection G. Michiels, nr. 54

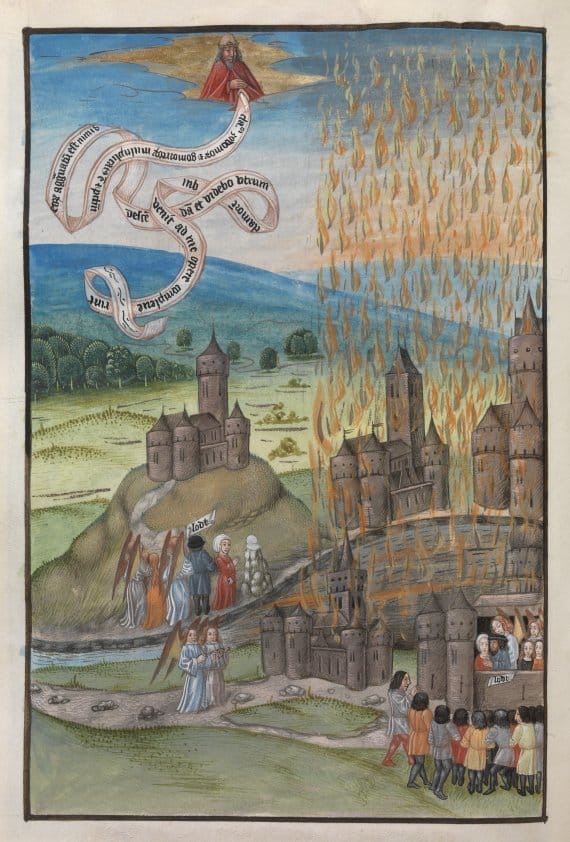

François and Willem were accused of sodomy. This Biblical term refers to the Old Testament story of Sodom and Gomorra. Both cities were destroyed by holy fire because the men were having sex with each other. In the late Middle Ages, the term sodomy was used to describe almost any sexual activity that did not have procreation as the goal. Masturbation, bestiality, anal sex between men and women, sexual abuse of children and homo-erotic activities were all referred to as sodomy. Society placed a series of sexual activities that we do not even associate with each other under the umbrella term ‘sodomy’.

At the stake

The concept of ‘sexual orientation’ did not even exist. Committing sodomy was considered as an individual’s choice. And it was a choice that could have severe repercussions. Sodomites were considered to be acting against the natural order and divine hierarchy and could potentially call down the wrath of God on society. Because of this, they had to be punished severely. Sodomites were sentenced to death by burning at the stake. In certain cases, the fact that an individual had not initiated the sodomy but was only a passive participant, was taken into account. They were sometimes ‘lucky’ enough to receive a lesser punishment. This was the case with François and Willem.

Anonymous, Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, from Biblia Figurata by Raphael de Mercatelis

Anonymous, Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, from Biblia Figurata by Raphael de Mercatelis© Archives of Saint Bavo's Abbey, Ghent

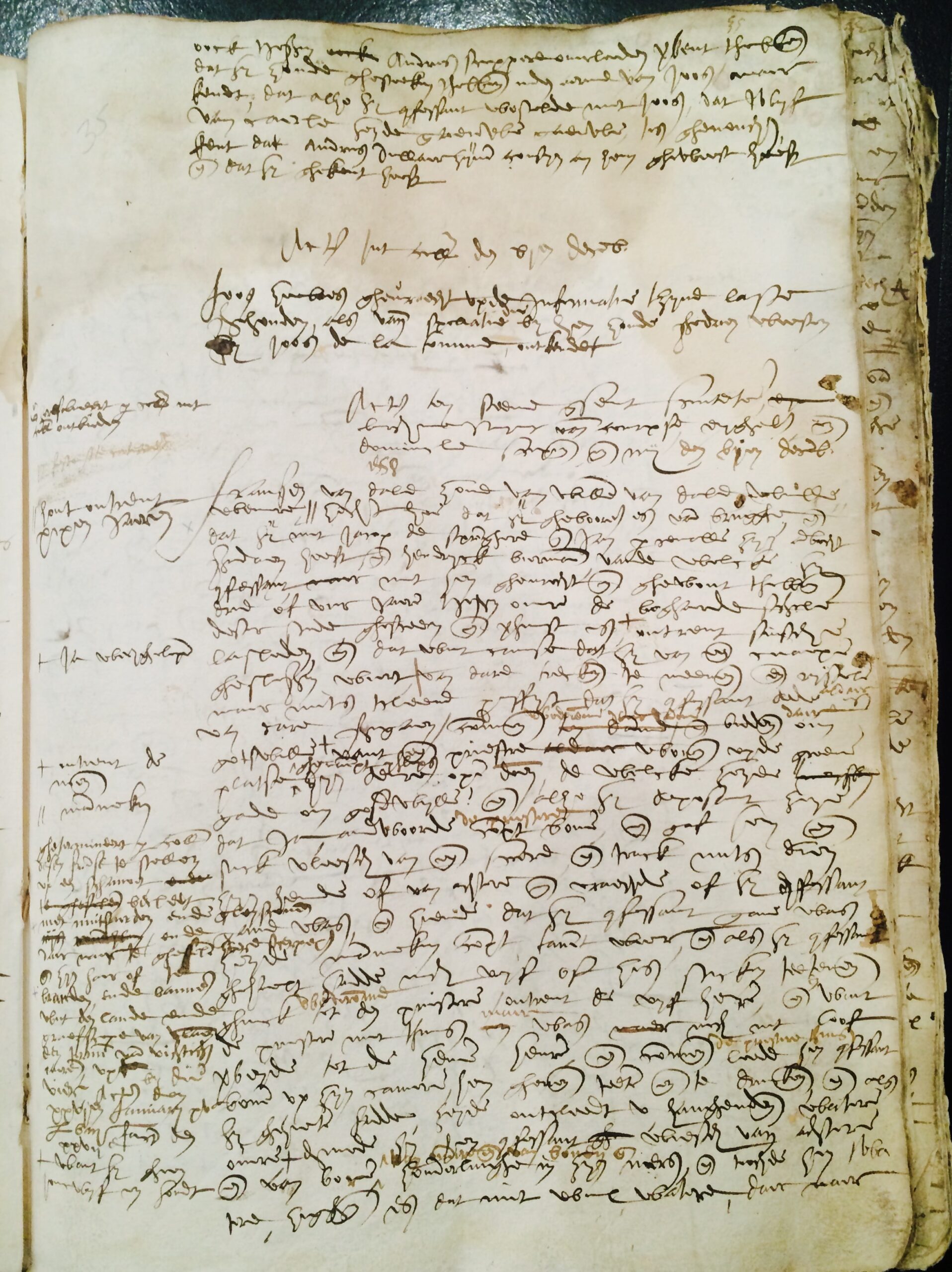

The story of the two boys can be found in the Bruges’ ‘Bouc vanden Steene’, which includes the accounts of all questioning and confessions under torture in the prison. These statements were, thus, made in the torture chamber. From that account, it appears that the priest with whom they had sex had some rather unorthodox preferences for someone of his background. The priest met the boys in the Sint Jan’s Hospital in Bruges and regularly invited them, individually, to spend the night with him at home.

There, they had sex, during which the priest masturbated and had penetrative sex with François and Willem several times. Apparently, he first liked to penetrate the boys anally with a candle before he had sex with them. Or, in the words of Willem: ‘ende nam een hende van een kerse ende stack hem confessant dat in zyn fondament ende datte terstont wut treckende stack zyn mannelickheyt in zyn fondament’.

Excerpt from the interrogations of François and Willem, Bouc vanden steene (1558-1559)

Excerpt from the interrogations of François and Willem, Bouc vanden steene (1558-1559)© City Archives of Bruges

Somewhat naively, the boys described how the priest did this several times in a row until some ‘wetness came out of the priest’s “manhood”’ (‘natticheyt uit de ‘mannelickhede’). It seems that he did not solely prefer boys. On one occasion the priest failed to get an erection while having sex with Willem. Afterwards, according to the boys, the priest complained that he could not ‘become erect, even if he were with all the women in the world (‘al ware ic tusschen alle vrauwen van de werelt, ic zoude niet staen’).

Clerical protection

Despite this setback, the sexual activity between the priest and the boys continued. During the day, the priest had to celebrate mass but on one occasion, before he prepared for mass, he first commanded Willem to wait for him in the bed, and then after mass came home and had sex with the boy. The behaviour of the priest was anything but what one might expect from a religious man.

Although sodomy was an ‘unnameable sin’, clerics were punished much more lightly than laypersons

Still, he does not appear at all in the legal documents of the Bruges’ magisterial courts. Priests were, in fact, protected from prosecution under secular law. They were only answerable to the ecclesiastical courts. However, the priest in question did not even appear there. It is unlikely that he was punished as severely as François and Willem.

Although sodomy was an ‘unnameable sin’ and one of the most serious transgressions a person could commit, clerics were punished much more lightly than laypersons. Generally, they were fined or made to fast on bread and water in the ecclesiastical prisons for a while. Sometimes they were banned from going on, or forced to undertake, pilgrimages, but were usually spared the physical punishments.

The sins of youth

François and Willem certainly could not count on that kind of protection. Even their youth was not considered a mitigating circumstance, though it could be in other places. In other cities, for example, Florence, homo-erotic activity involving adolescents was often viewed as a youthful indiscretion. It was not considered abnormal that young men who were not financially able to marry and set up a household would gain sexual experience from each other as a rite of passage into adult life.

In Florence, homo-erotic activity involving adolescents was often viewed as a youthful indiscretion.

In Florence, homo-erotic activity involving adolescents was often viewed as a youthful indiscretion.That kind of reasoning was not common in the Southern Netherlands. Probably due to the fact that there was no hard and fast rule determining when adolescents could be considered as adults and, therefore, be held responsible for their sexual activities. In the Southern Netherlands, legal age was determined by social custom, which varied from one place to another. This ambiguous situation left the door open for the local courts to make ad hoc decisions in cases involving adolescents. While one 14-year-old might be considered an innocent victim of sexual abuse, another might be accused of committing sodomy and would be severely punished.

This ad hoc approach was responsible for the high number of prosecutions in the Southern Netherlands. While doing my doctoral research, I compiled the numbers of sodomy charges between 1400 to 1700 in Antwerp, Bruges, het Brugse Vrije (the Franc of Bruges), Brussels, Ghent, Ypres, Louvain and Mechelen. Extensive archival research into numerous legal documents indicates that in that period at least 204 trials were held, involving 406 individuals. No less than 252 of the people charged had to suffer for their ‘unnatural’ sexual predilections ended up at the stake. More than half of the defendants who were accused of sodomy in the Southern Netherlands were, therefore, put to death.

These macabre numbers contrast starkly with the situation in the rest of Europe. In other cities, such as London, Paris and Amsterdam, sodomy cases were rare in the 15th and 16th

centuries. The Southern Netherlands was, thus, one of the most active regions in Europe for prosecutions for sodomy in the Medieval and Early Modern periods.

Scapegoat theory

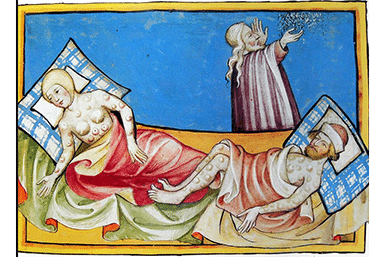

There is no single cause for these high prosecution figures. On the one hand, they serve as an example of Scapegoat Theory, developed by Robert Moore in 1987. He proposed that authorities in the Middle Ages were increasingly looking for ways to marginalise minority groups. The focus on these groups as the collective enemies of society served as a lightening rod for community unrest. Prosecuting a scapegoat creates the illusion that the authorities have any social crisis under control.

Depiction of the Black Death in the Toggenburg Bible (1411)

Depiction of the Black Death in the Toggenburg Bible (1411)Scapegoat Theory is certainly applicable to Bruges, the city where François and Willem were sentenced. Between 1450 and 1550 the city was struggling. Bit by bit, Bruges had lost its monopoly as the most important trading centre in Western Europe. After several cycles of plague in the 14th century, the population had decreased and, although many luxury goods were still bought and sold in Bruges, the city seemed to be past its heyday. The end of the 15th century was marked by political revolutions that caused a great deal of unrest: unrest that was fatal to the mercantile climate of the city.

Additionally, the silting-up of the Zwin meant that direct market access between Bruges and the North Sea could not be maintained. Foreign merchants increasingly chose to move their business activities to other cities in the Netherlands such as ‘s Hertogenbosch or Antwerp, which eventually took over the title of most important port town in the region of Bruges.

Whether by accident or not, the timing of the socio-economic stagnation in Bruges coincides very neatly with the increasing number of sodomy cases brought in the city, the majority of which were recorded between 1450 and 1525. It is in times of social unease, more than in moments of flourishing prosperity, that scapegoats are needed.

Social background

Still, we should be cautious in applying Moore’s scapegoat theory. He places the responsibility for the search for undesirables almost fully on the church and secular authorities. Other historians emphasise that, in the past, sodomy was used as a handy tool in of the modern state-building process. The prosecution of a minority group was, as a result, viewed as a way of showing the local population who was the boss in Bruges. Although this element certainly may have played a role, we can hardly expect that the Burgundian duke Phillip the Good or the Spanish king, Phillip II, could monitor every bedroom in Bruges for irregular behaviour. Even for the local bailiffs, the ruler’s representatives in the city, this would have been a Herculean task.

A group of homosexual monks is taken away by soldiers near the city wall of Bruges. The print refers to the trial of the monks in 1578 (see above).

A group of homosexual monks is taken away by soldiers near the city wall of Bruges. The print refers to the trial of the monks in 1578 (see above).© FelixArchives, Antwerp

The urge for stronger approaches to sodomy must, therefore, have been supported at the grassroots level. Sodomy was a ‘crime’ that, in comparison with other crimes such as theft or murder, rarely left any trace. Certainly not when homo-erotic acts, forbidden according to the municipality, were consensual. Naturally, this was not the case for acts of failed seduction, in which sexual advances made at the local hostelry or bathhouse were not welcomed by certain people, who then took the erstwhile seducers to court. In many sodomy cases there was no hard evidence so local magistrates often depended on the local gossip mill when following up on cases of sexual deviancy.

In many sodomy cases local magistrates often depended on the local gossip mill when following up on cases of sexual deviancy

In such cases, a person’s social background played a significant role. In cases of sodomy where the accused was upper middle class, married, a responsible citizen and pursuing a trade… they could count on witnesses who could enter favourable pleas in the case. This was less likely to occur in cases where a defendant who was already part of a marginal group or community was accused of sodomy. Migrants and undesirables, who were often already considered suspect, are over-represented in these cases in many regions of Europe. This was because gossip about these groups was often already circulating and, as a result, they were handed over to justice much more readily.

Erotic fates

How the sexual activities of François, Willem and their priest ended up in the court, we do not know. It is likely, however, that their erotic escapades were already the subject of local gossip in Bruges. Rumours concerning the priest, who lived with the boys the ‘way a man lives with a woman’ (‘dat hy met hem confessant soude leeven of gheleeft hebben ghelick met een vrauwe’), appear in the documentary evidence.

The priest was kept out of the picture while the two boys paid the price

That even the erotic fate of a priest came to the ears of the authorities by way of local gossip says something about the spirit of the times in 1558. Clerics were exempt from trial in the secular courts, but the population still gossiped about them freely. It is possible that the Reformation, the effective spread of Protestantism and the criticism of the many abuses perpetrated by priests in the Southern Netherlands may have had fuelled this gossip. But it is equally possible that this case came to light because the poor socio-economic situation in Bruges heightened the need for a scapegoat and the denunciation of behaviour considered unacceptable. Nonetheless, certain ancient traditions persisted; thus, the priest in question was kept out of the picture while the two boys paid the price.

In this sense, the case of François, Willem and their priest symbolises both the intense repression of sodomy in Bruges and scapegoat theory. Furthermore, this story illustrates the importance of social capital and the double standards that dominated the prosecution of ‘deviant’ sexual behaviour. In this manner, this case may even serve as a mirror for contemporary society.