Matea Bakula Looks for Material Reincarnation

As an artist, why would you ignore the natural capabilities of your materials? Sculptor Matea Bakula prefers to work with cardboard and polyurethane, amongst other things, because of their specific character and ‘behaviour’. Bakula reimagines what seems so common and known to us. In her future work, she looks to let plastics ‘reincarnate’.

Matea Bakula

Matea Bakula© Lienke Roos

‘What you see is what you see’, posited painter Frank Stella once. It became a famous slogan for minimal art, a movement popular with sculptors. Geometric, basic shapes like the cube and the rectangle were often favourited: their universality, combined with a sleek finish, allowed for a certain anonymity. These shapes make a return appearance in the work of sculptor Matea Bakula (Sarajevo, 1990), but rendered radically different: for her, they are not a destination, but a starting point. They are elementary to the extent of recognizability. That is why they are capable of triggering the viewers’ imagination.

Transcendence, 2020, cardboard, India ink, steel

Transcendence, 2020, cardboard, India ink, steel© Peter Tijhuis

Model scout for materials

Whenever an artwork forces a certain interpretation too obviously, it loses interest for Bakula. A successful sculpture has the capacity to call forth a variety of interpretations, which she loves to hear. Her eyes come alive when I compare her cylinder-shaped work You Have Two Challenges Remaining (2016) with broken cigarette butts – her work seems keen to resist the constraints of the tight, geometric shape.

You Have Two Challenges Remaining, 2016

You Have Two Challenges Remaining, 2016© Robin Meyer

However, it is often difficult to put a finger on what you are looking at. In that context, it is interesting that Bakula describes her process using metaphors and comparisons. She traces this tendency to her immigration to the Netherlands, when she was still very young. She was raised trilingual, speaking Servo-Croatian, Dutch and English. Whenever she has difficulty recalling a word in either of these languages, it often helped to describe it or use a metaphor. The same process becomes felt when viewing her sculptures: in their simultaneous familiarity and mystery, you find yourself grasping for comparisons.

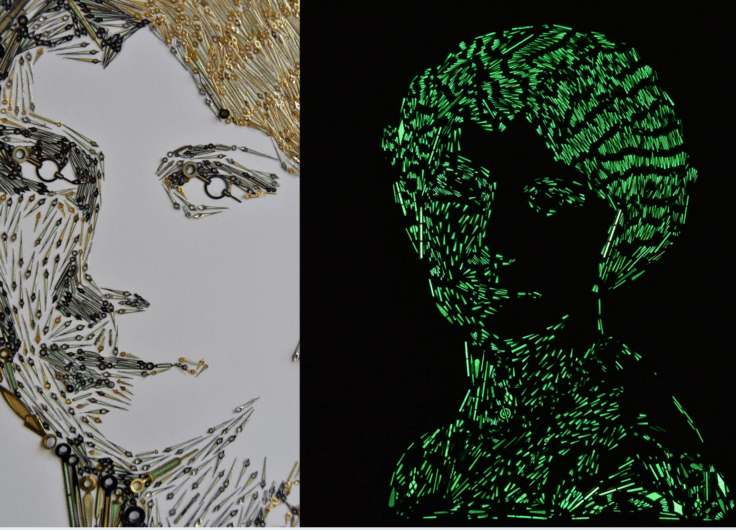

Ekatarina, 2020, cardboard, polyurethane rubber, copper foil, steel

Ekatarina, 2020, cardboard, polyurethane rubber, copper foil, steel© Peter Tijhuis

Bakula was already exploring the potential of widely varying materials, but it wasn’t until her graduation year that she realised she could “just” make this the focus of her work. By now she has developed a trained eye that she compares to that of a model scout. They don’t just see an attractive woman walking down the street, but a future cover model, because they instinctively know which make-up and expensive dress she needs.

Similarly, Bakula recognizes in her materials – among which polyurethane foam, cardboard and wax – its potential: not only in terms of what she could make out of it, but also if it could prove interesting as an artwork. Transformation is key: giving the material a function and place that are unusual, but still shows its original purpose. In this way, Bakula shines a new light on the ordinary.

Paper column

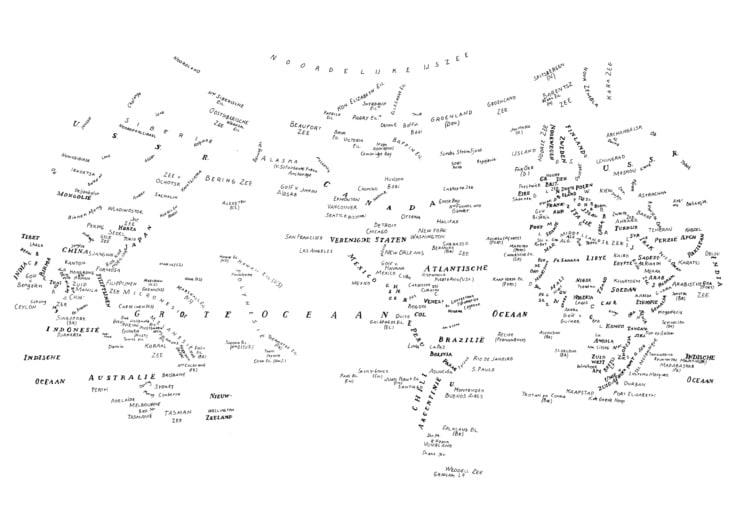

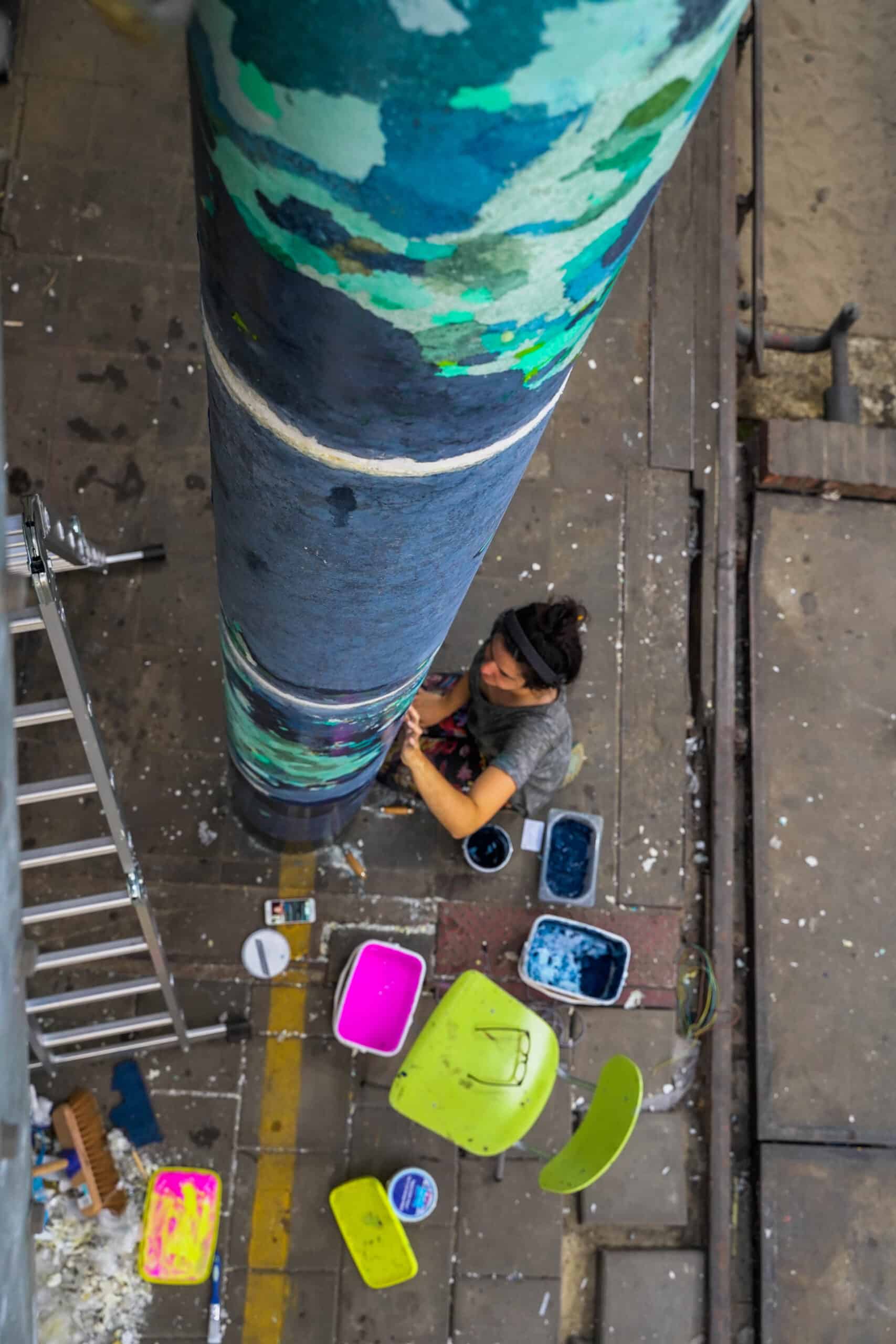

A Letter From a Free Man, 2020, paper and dyes

A Letter From a Free Man, 2020, paper and dyes© Wiel Wijnen

A fitting example is A Letter From a Free Man (2020), a six-meter high column Bakula made for The Utrecht Archive, in her hometown. From the perspective of one’s architectural knowledge, it would be tempting to assume that traditional materials such as marble were used. As you approach the work, however, you can derive from its surface that it is not as solid, shiny and sleek as first thought. It has small dents and blemishes that are reminiscent of cardboard or, to be more precise: cardboard that has become wet, not yet mushy but a precursor to it.

To be fair, I did cheat a little when viewing A Letter From a Free Man, as I already knew it was made of paper, but still: it is remarkably easy to let go of that knowledge. From afar you forget it: you find yourself watching a solid sculpture – a thing you can’t ignore when seeing the texture up close. But take only one step back and the grandiosity returns. The thing you see seems clear and manageable, yet still seems to subtly keep changing shape.

A Letter From a Free Man, 2020, paper and dyes

A Letter From a Free Man, 2020, paper and dyes© Wiel Wijnen

Bakula was one of the artists who could submit a proposal for an artwork at The Utrecht Archive in 2019. There she witnessed enormous amounts of documents and papers, preserved in large drawers. That in itself she found fascinating, but then she learned about the effort that goes into preserving the paper in its original form.

Even though Bakula appreciated that need, she submitted a proposal for a sculpture of which the materials – paper and colourants – would be given the space to change. The column will be on-site for half a century, if not longer, and over time parts of it will discolour in some way. For Bakula, this normally unwanted transformation was provocative.

From polyurethane to plastic

However, in her studio it is not just Bakula who goes against the grain: her materials have a mind of their own too. It is a challenge for her to engage with that, even though she can never fully control it. Once she truly starts working with a material, she often feels like a choreographer giving a dancer instruction, after which they put their own spin on them.

Shapeshifting, 2020, cardboard, steel, beeswax, polyurethane rubber

Shapeshifting, 2020, cardboard, steel, beeswax, polyurethane rubber© Peter Tijhuis

For example, she references the aptly titled Shapeshifting (2020): two circular objects of twisted cardboard. They are not perfectly (in other words well-behaved) round, but rather egg-shaped. It led to the often-received question: whether that was intentional? Of course, is Bakula’s answer in moments like these, because this is what cardboard does. She already knew that when she started the piece. She could have taken measures to prevent this curling and force the circles into a perfectly round shape. But if you ignore the qualities and behaviours of cardboard or any other material, why would you keep working with it?

Bakula describes the next step in her practice as a shift from material transformation to reincarnation. The biggest difference in doing so it that the latter indicates recycling, offering wider contextual meaning to the material. Also, she has become reluctant to using polyurethane: too chemical and polluting. She realized that her artistry is not an excuse for leaving an ecological footprint.

The column from A Letter From a Free Man is a prime example of reincarnation, just as the earlier mentioned Shapeshifting, for which she re-used the wax moulds used to make The Unlimited B Pole (2018).

The unlimited B pole, 2018, beeswax and wood

The unlimited B pole, 2018, beeswax and wood© Robin Meyer

In the near future, she wants to research the potential of plastic. In its versatility, it is much like polyurethane and is so widespread and momentarily used that sustainable recycling seems appropriate. It can last centuries (like a water bottle) or never disappear at all, like the microplastic in cleaning agents.

Wouldn’t that be the perfect material to bring renewed attention to through long-term engagement? Her intent is not to present obviously recycled materials, because that would be too unambiguous. It is about transformation, about what plastic could become, without recognizing it as such. Bakula is the perfect artist for such a task: her sculptures are an invitation to continuously enrich your gaze.