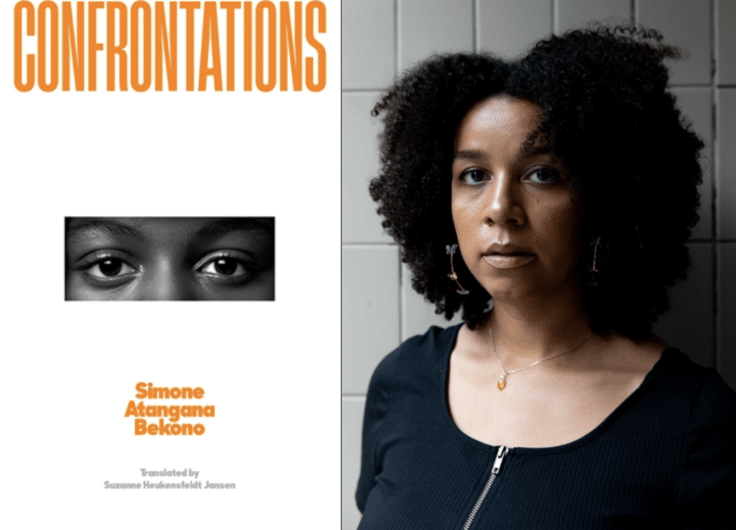

Simone Atangana Bekono’s ‘Zo Hoog De Zon Stond’ Translated Into English

In February and March of this year, students from The University of Sheffield and University College London embarked on a collaborative project to translate an excerpt from Zo hoog de zon stond (2022), Dutch poet and writer Simone Atangana Bekono’s second novel, following on from the success of her debut novel Confrontaties (2020). Zo hoog de zon stond – or in our translation: High Was The Sun – was also nominated for the 2023 Libris Literatuur Prijs.

The reader follows the ‘geflopte’ (to quote de Volkskrant) artist Sonny on her summer-long Grand Tour back to her roots, i.e her home-town, after a failed attempt at making it big in San Francisco. The very setting – an intense summer heatwave in a once familiar but now alien hometown – feels almost uncanny, which sets Bekono up to play freely with the gothic genre in a modern setting. Bekono uses a particularly personal mode of writing which allows the reader to feel personally close to Sonny as she goes through what can only be described as a quarter-life crisis. The image that Bekono paints of the protagonist – young adult, stoner, struggling artist, struggling to find their way in life – all of this paves the way for the uncanny valley-esque experience and identity crisis that take place later on in t’ huuske.

Students of the University of Sheffield and UCL at work with Jonathan Reeder and Simone Atangana Bekono.

Students of the University of Sheffield and UCL at work with Jonathan Reeder and Simone Atangana Bekono.Discussing our different versions of the translation was very fruitful and rewarding, as issues that didn’t appear to me during my individual translation were brought to light, and vice versa. The demographic that Sonny belongs to posed several hurdles in the translation process. As a young person living amongst a ‘hip’ community of artists in San Francisco, many of her friends speak to her in English: “San Francisco doesn’t fucking suit you”, for example. Maybe it doesn’t suit her; but do we have to change the way English is used in a Dutch novel?

Thanks to the guidance and advice of professional translator Jonathan Reeder we were able to discuss and overcome such subtle issues that often slip the mind as a reader, but need to be analysed as a translator, for example the difference between British English and American English, and whether the context of San Francisco alters this.

With many thanks to the University of Sheffield and UCL Dutch departments, the Dutch Language Union, the Dutch Foundation for Literature, Jonathan Reeder and Simone Atangana Bekono for their support, without which the project wouldn’t have been possible.

Alex Sullivan (University of Sheffield)

Editorial team: Daniel Corcoran, Hadyn Geary, Alisha Mallya, Nitya Raghava, Jonathan Reeder, Angela Zhou

Translators: Brooke Ackroyd Charnock, Abigail Ani, Ynys Convents, Daniel Corcoran, Alice Garside, Hadyn Geary, Matthew Gibbons, Louis Goddard-Glen, Brad Hampshire, Mohamed Illeye, Robert Jones, Alisha Mallya, Catherine Newell, Robert Pearce, Nitya Raghava, Elliot Ridsdale, Liam Stoddard, Alex Sullivan, Angela Zhou

Tutors: Filip De Ceuster and Christine Sas

Project Coordinator: Henriette Louwerse

A short video report of the project.

Excerpt from 'High Was The Sun' by Simone Atangana Bekono

I.

She had cut her losses. In short, she was broke, hungry and stoned in her little room with her laptop when she booked a ticket from San Francisco to Amsterdam with the last of her money. One way. Two months of living off kids’ menus in fast food joints, sugary cereal, dodgy weed and little praise had taken its toll. Sonny was done with putting herself through this. She woke up that day and thought to herself: enough. She wouldn’t disappear. She would leave it all behind, like a strange memory, a bad dream, and pull her shit together, start again. She would go home and forget it all.

When the email with her ticket arrived, she let out an audible sigh of relief, took a hit on her vape, and curled up in the middle of her bed. She had cut her losses, she told herself reluctantly through her clenched jaws, lying on the musty mattress. And she wouldn’t disappear. Not her, not Sonny.

Her residency had been a complete disaster, with inspiration eluding her. She had fled from Barcelona to San Francisco, leaving behind an irritated flatmate, a furious client, and a downright homicidal coke dealer, following the advice of her best friend Samuel.

‘Do something with your life and get the hell out of Spain,’ was what he’d told Sonny when she facetimed him from the lounge of a backpackers’ hostel, on the run from the constant stream of threatening messages from Fernando, the dealer. Then, Samuel had sent her links to an artists’ residency in Malta (‘hard no’), South Tyrol (‘Who do you think I am, James Baldwin?’), Tel Aviv (‘very funny’) and San Francisco.

Once she got to San Francisco, Sonny quickly realised that fate had led her to America just to show her how much she was truly screwing up her life. The artists she shared the studio with were serious, stylishly dressed, focused, successful. Some, Sonny realised to her absolute horror, were younger than her. She felt like a loser there. Nobody was interested in her work. She could barely make ends meet on her savings as she pushed paint around on her canvas, watching the clock each day, waiting for it to strike five so she could make her way, head slumped, to the nearest bar, a sports bar just across from the renovated warehouse that was home to the studio. The gallery owner and residency leader – a small, ethnically-ambiguous woman called Kashmere – took Sonny under her wing, taking her out to eat once a week, usually to ask her with some concern what on earth she was doing.

Kashmere had encouraged her return.

‘San Francisco isn’t for you,’ she had said at a fusion restaurant, when Sonny announced that she was leaving. ‘Go back to taking photos. Back to your roots. I’ll find someone else to take your place.’

As soon as Sonny had booked the ticket, she put her unfinished paintings in the skip, cleared and cleaned her workplace and started packing her bags. She left four days later without saying goodbye to the other artists she had shared the studio with. In her tiny bedroom she left behind a fridge with a half-eaten bucket of fried chicken and an opened bottle of white wine. She placed the vape and the cannabis oil at the back of the wardrobe, on the top shelf, for someone else to enjoy. In the Uber on the way to the airport she tried to find some kind of feeling inside her body, something akin to an emotion that she could connect to her leaving. But there was nothing. She felt empty. Done.

Now that the borders were open again, Sonny’s parents decided to spend the summer with her father’s family in Cape Verde. This meant she could keep subletting her studio in Rotterdam to the Polish watercolourist, and then live off the income in her hometown for now. No-one would know that she was back in the Netherlands. No-one except for Samuel, who she called while eating a nasty sandwich at the airport.

‘So, what’s going on?’ he said. ‘How come you’re going back home?’

‘Creative differences,’ Sonny said. Then, out of shame, she added, ‘I’m going to do something completely different, I think. Maybe carry on with my final project from art school. Approach things from a different angle.’

Samuel responded enthusiastically to that.

‘Hell yeah! Take some photos, meet up with some old friends, go for a swim in a lake or something.’

‘There aren’t any lakes there,’ Sonny said, and she remembered that Kashmere also said that she should take up photography again.

Sonny didn’t believe in omens.

‘A swimming pool, then?’ Samuel looked away from his phone out of boredom. Then the image got scrambled. It was probably because he was facetiming from the balcony of his Airbnb in Marseille, where he was on holiday with his boyfriend.

‘Public pools are gross.’ Sonny wiped off the mayo on her mouth and threw the half-eaten sandwich into the bin by her seat.

‘Then find someone with a private pool.’ Samuel blew smoke at the camera and Sonny hung up, making the excuse that her flight was boarding.

She slept badly during the flight. Even though the return felt less like a defeat because she wasn’t going to Rotterdam, but her hometown instead, where no one knew her and no one would come up to her in the shop asking why she wasn’t in America anymore, the feeling that she was making the wrong choice still hung over her. This journey home could signal the end of her career. Although she had to admit that over these past few years, everything had felt like a career-ending mistake. Every decision she had made felt like one too many, as if she had drifted further and further away from where she wanted to be, from the insight she needed, from a sense of clarity and purpose. As if she kept looking away too soon and missing out on the value of what was in front of her. She blinked and it was gone. On the plane she missed her vape, so she stuck nicotine patches on her arm, fidgeted about in her uncomfortable chair, and watched a crappy film.

During the flight, the embarrassment caught up with her. Dazed and panicky, she had stumbled her way through her time in San Francisco, and Barcelona before that, hoping that her growing unease would at least do her art some good, or maybe give it a sense of urgency. But it hadn’t. She’d only painted less because of it, and now, altogether apathetic and without any new projects or insights, she had to make her way back home. All those pointless networking events. All those expositions which had cost more than they had brought in. The open call deadlines, the interviews with throwaway magazines. All the booze, drugs and half-remembered superficial contacts – sexual or professional, and far too often both. The past few years were shattered recollections, flashes of experiences, a compilation of scenes from a film she would rather not watch. The panic she had felt in San Francisco, the panic which had been brewing for a while up to almost crippling proportions, was genuine. She’d had momentum when she graduated from art school. But it had either wasted away or had slipped through her fingers. In any case, she’d lost it. The chance that it would come back, that she could learn from her missteps or turn them into something positive, was slim. And she felt that it depended on this particular summer, spent in her family home until her father and mother came back from Cape Verde.

That last idea kept coming back. The idea that it had to be this specific summer that would see her change the course of her life. Otherwise, she’d be done for. Forever too late. Time to pack it in. The upward trend which had once defined her career, after reaching a brief peak, had entirely stagnated. No, to be honest, it was in a downward spiral. She hadn’t done anything about it because she hadn’t been there. Not really. She’d lost her focus. But she had to crack on soon. Seriously crack on. No more drugs. No one-night stands. No angry dealers or disappointed gallerists. She had to fight the anxiety. She had to stop giving in to her slow demise. Just honest work, and therapy. Only those two things: work, and therapy. She would contact a psychologist again and take up photography again. Therein lay the solution – in photography and a sober mind.

She didn’t believe in omens. In the time it had taken her to catch the train, the bus, and then the dial-a-bus to her village, the time it had taken her to walk from the bus stop to her parent’s house, dragging her enormous suitcase behind her, her fire had seriously been reignited, her almost dogmatic certainty that photography would save her.

She was standing at the front door of her parents’ house when she realised she’d completely forgotten her key. It was, of course, in her flat in Rotterdam, safely stashed in the porcelain dish next to the front door. She’d left it there two years ago, just before she set off on her Grand Tour. And now, in the middle of July, at the start of what would be at least a week-long heatwave, she stood at her parents’ door. A white door, of which the top half could open separately, with a big, brown-tinted window that let you see every visitor from head to chest. She stood in front of that door, in the middle of the day, with an enormous suitcase against her hip, seriously jet-lagged, sweaty, exhausted, and thirsty. She was dying of thirst. She stood in front of the door. Locked out.

Sonny could just melt away here on the driveway, dripping slowly onto the tiles, liquefying completely until she trickled through the cracks, disappearing into the earth below. Gone. But that would just defeat the purpose of being there. Her head was spinning, her legs tingling from fatigue. She messaged her parents, but they didn’t respond. She drank the last of her water. She laid her suitcase down flat and, sitting on it, looked over at a group of teenage girls cycling by with long, flowing hair, leaving a trail of sweet perfume in their wake. They were probably off to some café in the village. She realised she no longer knew anyone here who could help her. But she wouldn’t disappear. Everything depended on this summer. And so she had to get inside, no matter the cost.

II.

It was humiliating. To give up already, get back on that bus, kick the Polish watercolourist out of her studio, sleep in her unmade bed, and to feel ashamed – just the thought of it filled her with so much disgust that she sprung to her feet. She pulled a bent cigarette out of the packet in her pocket and lit it. No, she decided. Work and therapy. Therapy and work. What did she have to do to make sure she wouldn’t disappear? She had to get into her old house. She had to open the door.

And so her mind was made up. She smoked the rest of her cigarette and chucked the butt towards the street, where it bounced, sparking, along the tarmac before finally landing in the drain. She rolled her suitcase aside, slipped her rucksack from her shoulders, pulled her smelly T-shirt off and wrapped it carefully around her right hand. She’d seen enough actors do the same in films, seen men do it after going out. She’d seen her uncle do it once, at the end of a birthday party, drunk and furious at her aunt, who he’d been arguing with for most of the evening about something that Sonny had long since forgotten. Sonny’s father had driven him to hospital afterwards, laughing and slightly tipsy, while her mother and aunt swept up the shards of glass from her aunt’s kitchen window.

‘I’m leaving him!’ Sonny’s aunt had sobbed. Sonny’s mother then rolled her eyes whilst patting her sister on the back.

But this wasn’t just about cheating, or love, or getting drunk. Sonny breathed in deeply. She thought about the seams of the world, of how fluid she was, and how easy it would be to seep down into the cracks. She breathed out again. She slammed her fist with all her might against the front door windowpane. Again, and again, and again.

Save for making her knuckles sore, her first blows had no effect. But Sonny had to and would get inside. She knew that in summers past her father had enjoyed smoking a cigarette, sitting on the stack of paving stones in the front garden, leftovers from the building of the garden path. ‘Right then’, she thought. She went into the front garden and lifted one of the tiles from the pile. Awkwardly shaped and heavy, she had to hold it with both hands and decided to lift it overhead and throw it against the window. Braced, arms raised, core muscles tightened, she threw the tile as hard as she could against the glass. A large crack formed in the window, but there was no breaching it. The tile crashed as it rebounded onto the driveway. Despite the protests of her lower back and burning arms, the crack she’d made in the pane filled her with a new bout of courage. Thinking about Barcelona, San Francisco, Kashmere, Samuel, and Paris, she lifted the tile once more and hurled it with all her might. Screaming out of anger and frustration, it felt surprisingly satisfying, apt, just. The tile landed with a loud thud on the wooden floor of her parents’ hallway, followed by the shrill, harsh sound of shards of glass raining down. Sonny glanced wildly around her, she spotted an old couple on e-bikes riding slowly through the street towards the main road, looking suspiciously in her direction.

‘Mind your own damn business!’ Sonny snapped, in a frenzy of adrenaline. The man sped up and the woman quickly followed suit. They fled, looking back over their shoulders.

The remaining glass just needed a nudge here and tap there. Sonny used her sunglasses case to tap the glass at the edges of the window and draped her T-shirt over the lower edge of the frame to protect her belly from the leftover shards. She carefully hoisted herself up and clambered through the hole, one leg at a time, eventually lowering herself into the hallway. She looked at the chaos and the chaos looked back at her. There was nothing left out of balance by her deed: it was justified. She then walked into the kitchen and turned the cold tap on. After staring at the yellowed grass in the back garden for a short while, Sonny took a glass from the kitchen cabinet, pushed it under the tap, and downed two full glasses of ice-cold water.

As she wiped her mouth and opened the kitchen window, she decided she would call her parents. She knew it was going to be uncomfortable. Her mum would go mental, her dad would burst out laughing, and Sonny would have to ask for money to get the window fixed, and to go food shopping. She would then tape two torn bin bags in front of the hole, have a shower, and take a nap on the sofa.