The Graphic Appetite of Comics Artist Typex

Typex, pen name of Dutch graphic novelist Raymond Koot, might refer to the famous correction fluid, but his work seems to be almost effortless. His illustrations, varied as they are, reveal the quality of timeless design, particularly the graphic spectacle of his cartoon biographies of Rembrandt and Warhol. In his latest work Je moeder! (Your mother!) he depicts life as it is in times of coronavirus.

Amsterdam graphic novelist Typex (Amsterdam, 1962) is one of the Netherlands’ best-known cartoonists. To give an idea of his name and fame: during a concert, rock star Nick Cave praised him as ‘the second greatest Dutch artist – first there was Rembrandt, then there was Typex.’ Cave and Typex came into contact through the iconic music magazine Oor, where for years Typex had been providing the illustration for the album of the month. His clients include other prominent Dutch magazines and newspapers such as the VPRO guide, Vrij Nederland and de Volkskrant.

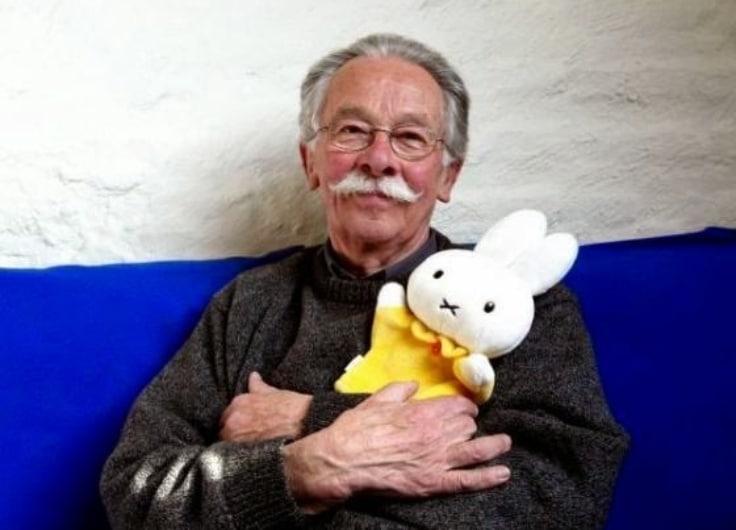

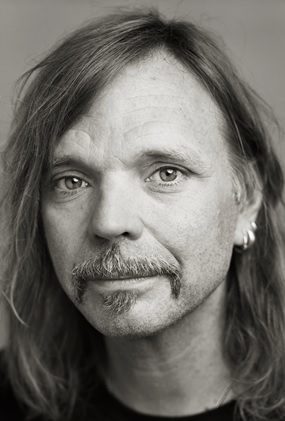

Typex

Typex© Ringel Goslinga

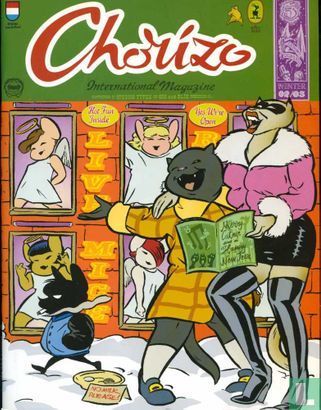

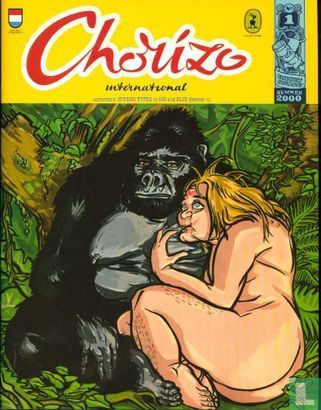

Initially the name Typex only received modest recognition in the world of comics and illustration. Until the magic year 2013 his comics were known as stubborn shelf-warmers that barely drew a glance, except among a handful of connoisseurs. Examples? His homage to Kick Wilstra, the football comic by Henk Sprenger that had been wildly popular in the 1950s. And that amusing magazine Chorizo, too, which only published three issues and in which, among other capers, Typex presented Fiep Westendorp’s innocent child duo Jip and Janneke in the guise of two randy mice. When the publisher went bankrupt the unsold stock was dumped on his doorstep, a blow of considerable dimensions, given the mountain that suddenly rose up in front of his door.

Most people might have given up at that point: not Typex. He continued to draw and at the same time to dream of books that would bear his name. ‘I like to be able to reread a book. People see my illustrations in magazines once and then they disappear like fish-and-chip paper. A book is for life,’ he noted in an interview.

A world-famous prick

So what makes 2013 so magical? April that year saw the reopening of the Rijksmuseum, the crown jewel of Dutch museums. After ten years of restoration, redecoration and other work behind the scenes, Queen Beatrix pressed a button, and, with orange fireworks bursting from the battlements, waved the heavy entrance doors open again at last. The opening of “het Rijks” was a people’s celebration with all the Amsterdam bells and whistles. One of the most frequently visited rooms houses The Night Watch, undoubtedly the most famous work by Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn. Illustrative of the painting’s great significance is that a year later it became the backdrop to a crowded press conference with then American President Barack Obama who was visiting the Netherlands at the time.

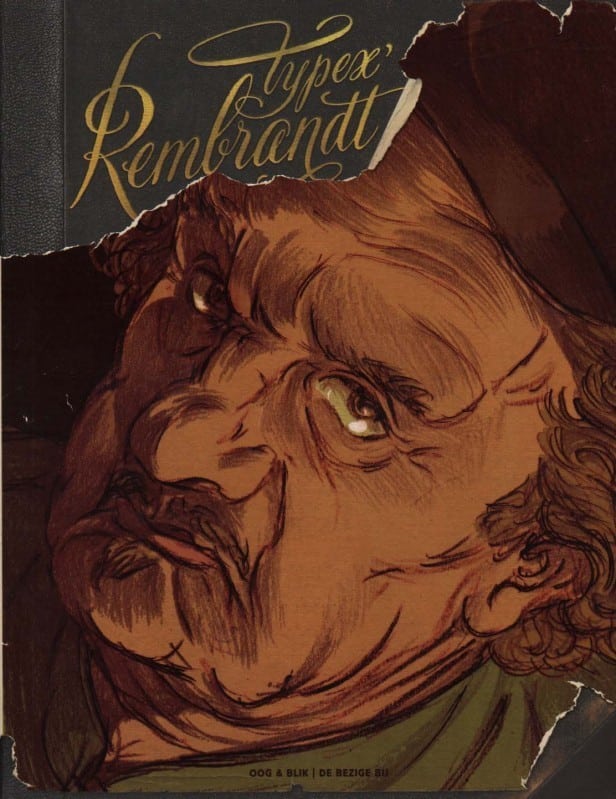

In honour of the reopening, the Rijksmuseum also published a tome of a graphic novel: Typex’ Rembrandt, illustrated and written by Raymond Koot, aka Typex. It might seem a surprising initiative for a prestigious museum, but perhaps the Rijksmuseum was following the example of the Louvre, its big brother in Paris, which for years has been letting famous comic strip artists loose with carte blanche in its galleries and depots, resulting in pearls by Jirô Taniguchi, Nicolas de Crécy, Marc-Antoine Mathieu, Éric Liberge, Bernard Yslaire and Lax.

For three years Typex worked on his interpretation of the life of the most famous painter of the Golden Age; he devoured everything he could read about Rembrandt, and eventually came to the conclusion that in essence there were few facts on which to hang the man’s life story. Items preserved include his life and death certificates, as well as a declaration of bankruptcy with an inventory of household contents. Here and there are snippets of text revealing a facet of personality, for instance by poet Constantijn Huygens, who visited Rembrandt’s studio and put pen to paper on the subject.

Typex: 'Biographies can’t lie, but I can'

Due to such limited sources, Typex opted to sketch each of the ten chapters on another figure from Rembrandt’s life: his wife and son Titus, as well as unknown characters – one of the chapters even revolves around a rat. This is Rembrandt through the eyes of others, not least those of Typex himself, who also worked on his own ideas and impressions in order to get the story moving. ‘Biographies can’t lie, but I can,’ he has said several times. Hence also the title: Typex’ Rembrandt. This was his version of the famous artist’s life. ‘He was a very complex person. And a prick.’ And so it is: in Typex’ eyes Rembrandt is irritable, rude, vain, mean, stubborn and sentimental. But also endearing and sometimes even pitiful.

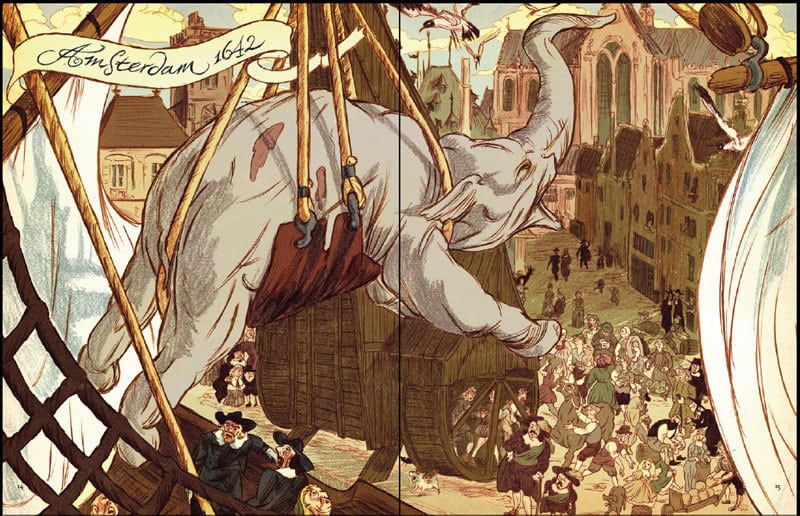

Drawing from Typex' Rembrandt

Drawing from Typex' Rembrandt© Oog & Blik / De Bezige Bij

The materials that form the visual basis for the book are the many paintings, sketches and countless prints which belong in the collection of the Rijksmuseum and elsewhere. Typex was inspired by Rembrandt’s many self-portraits: they too show that that the master was not a particularly jovial chap. Each chapter opens with a print by Rembrandt in the spotlight. In this way he makes the artist’s loose, searching lines his own, so that the distinction between authentic historical work and that of Typex blurs and melts away.

Drawing from Typex' Rembrandt

Drawing from Typex' Rembrandt© Oog & Blik / De Bezige Bij

The virtuoso illustrations also reveal the grimy, stolid quality of Rembrandt’s work. Take for instance the scene in the second chapter, in which Rembrandt seeks backing for the “operetta characters” of the militiamen, also known as “the night watch”. You know the ones, that painting we were talking about before. He turns up there, with brisk reluctance, among a clutch of carousers. The drunken, grotesque mugs of the company are so theatrical that it’s as if as readers we have landed in a cabinet of pickled curiosities. It’s almost as if Rembrandt himself has drawn a cartoon; it’s no coincidence that Typex has taken many of Rembrandt’s own images as starting points. What is Typex’, and what is Rembrandt’s, we wonder from time to time. Whatever the answer, the book was showered with prizes and soon found its way into other languages.

No mean feat

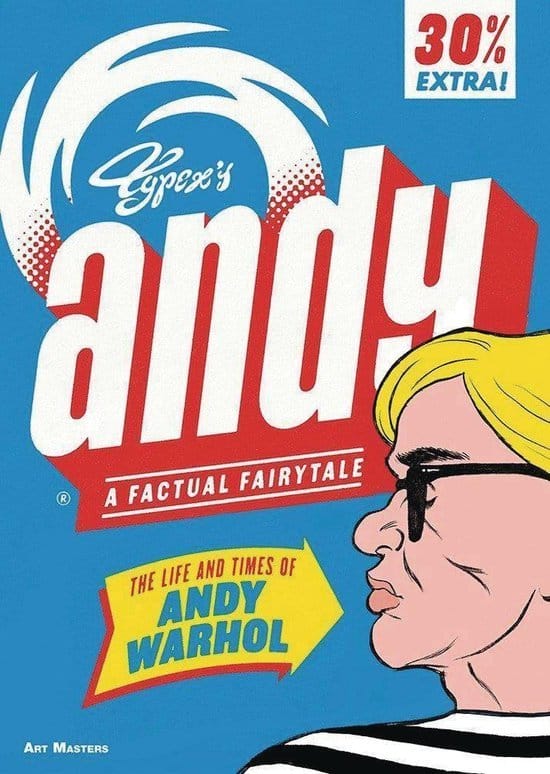

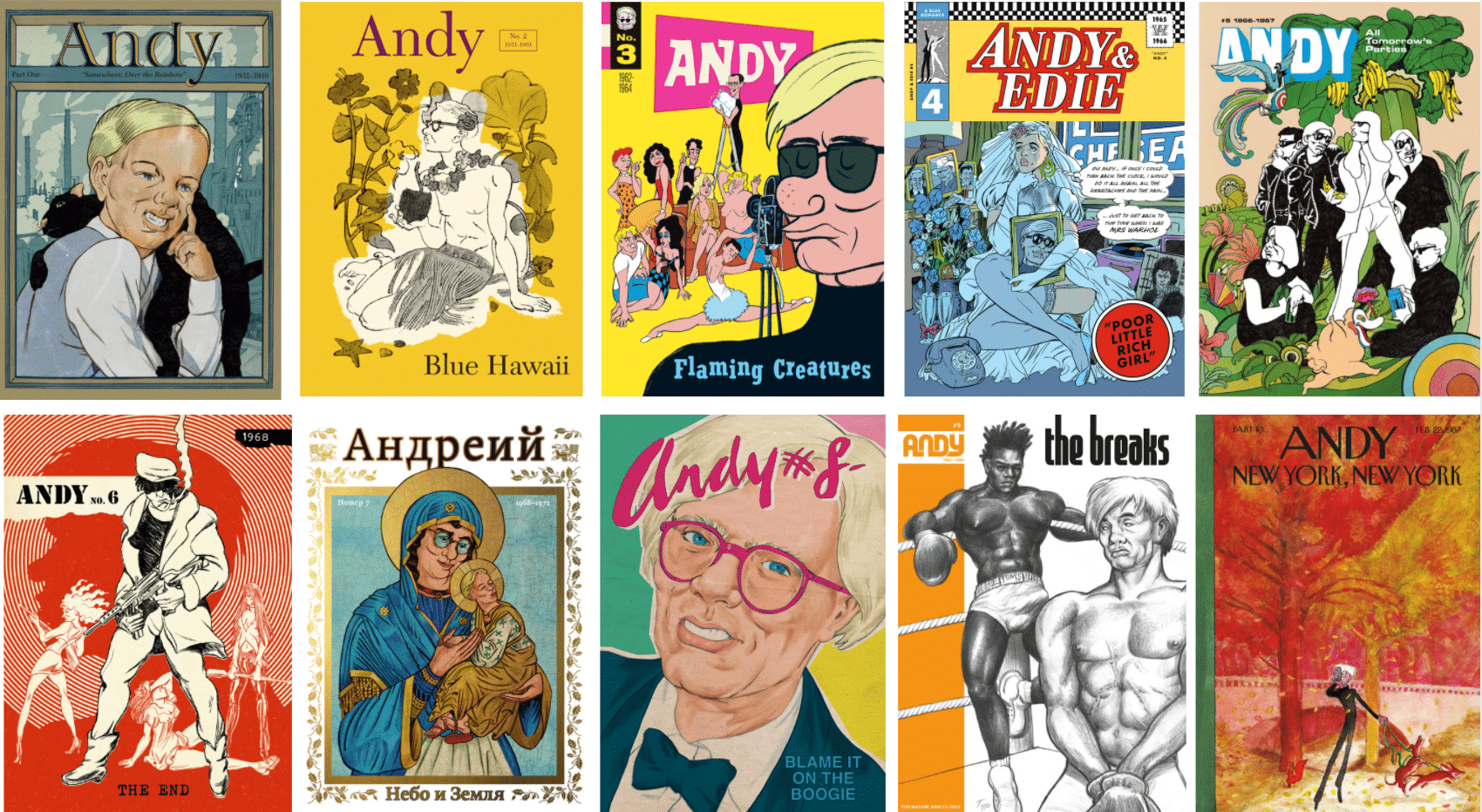

In interviews on the publication of Typex’ Rembrandt, Typex sometimes joked that in the last few years he had spent more time with Rembrandt than with his own wife, working more than eighty hours a week. Nevertheless at the end of 2018 another graphic novel biography of his appeared: Typex’ Andy, subtitled A Factual Fairytale. The life and times of Andy Warhol.

The book is monumental in every respect. It not only looks like a de lux washing powder box in gleaming silver print, it also weighs more than a kilo and a half and contains 562 pages. Each of the ten chapters is introduced with a page of twelve trading cards featuring the main characters of that chapter. So it’s another artist’s biography, and one of the most iconic artists of the twentieth century at that. Unlike with Rembrandt, there is a profusion of sources on Warhol, largely maintained by the museum that bears Warhol’s name in his birthplace, Pittsburgh. Typex worked away at the book for five years, and the cherry on the cake was the lively wrangling with the lawyers of the Andy Warhol Foundation in New York on all kinds of copyright issues. A cartoonist has to be a jack-of-all-trades.

Typex’ experience with the composition of Rembrandt’s life story paid off. He observed that the pile of biographies he’d read rehashed much of the same material. For instance, the idea that Warhol kept on saying things like ‘In the future, everyone will be world-famous for fifteen minutes!’ These endlessly recycled quotes and events create a fictitious figure, a myth. ‘I do the opposite: I try to approach the truth from fiction,’ says Typex. That is to say, from significant details and his own narrative view of a man who has made an indisputable mark on the international art scene and is often called “prophetic”. Warhol foresaw the rise of the selfie, our ever deeper sharing of our private lives, and he had almost his entire life filmed.

Typex' book on Warhol reads like an extensive mosaic of short stories, great and small

Unlike the canonised biographies of Warhol, Typex therefore opts for a catalogue of illustrative details from his life, such as a haircut, an item of clothing, or a concert. The book reads like an extensive mosaic of short stories, great and small, which, when you zoom out as a reader, convey a kaleidoscopic image of a person like you or me. With his minor flaws, for sure, but also with his sense of pose and (melo)drama, social ineptitude and graphical ingenuity, to pick a couple of examples.

That makes for a serious challenge to readers in terms of stamina. The book is monumental in every respect. In it he has Andy tell the band The Velvet Underground that if they notice people looking fed up after an hour and a half, they should go on playing for another hour. Perhaps not coincidentally on the back cover the author advises that readers stop after each section of the book to avoid indigestion. Warhol moved in a constant maelstrom of artistic impulses, crazy capers, drugs and drama. With peers such as Jackson Pollock, Roy Lichtenstein, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Lou Reed and countless others, even including the former American president, Donald Trump.

Typex' book on Warhol is divided into ten chronological chapters.

Typex' book on Warhol is divided into ten chronological chapters.The book is divided into ten chronological chapters. A prominent feature and proof of Typex’ skill: in each part of the book he deploys a different drawing style. The colours and techniques also play a role. Warhol’s life story begins in black and white pencil, in a time when colour TV and film did not yet exist. Of course advertisements in watercolours, screen prints, photo booth and Polaroid had to be included. In that evolving, explosive, graphic universe, Warhol really comes to life as a comic-strip figure. At a certain point he finds himself at a party in the mid-1980s standing next to the singer Blondie, who tells him she would rather go back to being called Debbie Harry, claiming to be fed up with life as a comic-strip character. Astonished, Warhol replies that he finds it so much easier to be a comic-strip character!

The book was published in fourteen countries and six languages at the same time, no mean feat in the world of graphic novels. And since then it has been inundated with praise from public and critics and nominated for the Grand Prix at Angoulême’s comic strip festival. In the Netherlands Typex’ Andy has sold out, although the ten chapters are still available separately.

Ordinary life

After two valiant biographies, will Typex bid farewell to the genre? At the end of 2018 he declared in an interview, ‘I’m done with biographies now. To be honest I don’t much like them. I don’t like their literal quality. I start out from the facts, but I make my own story out of them.’

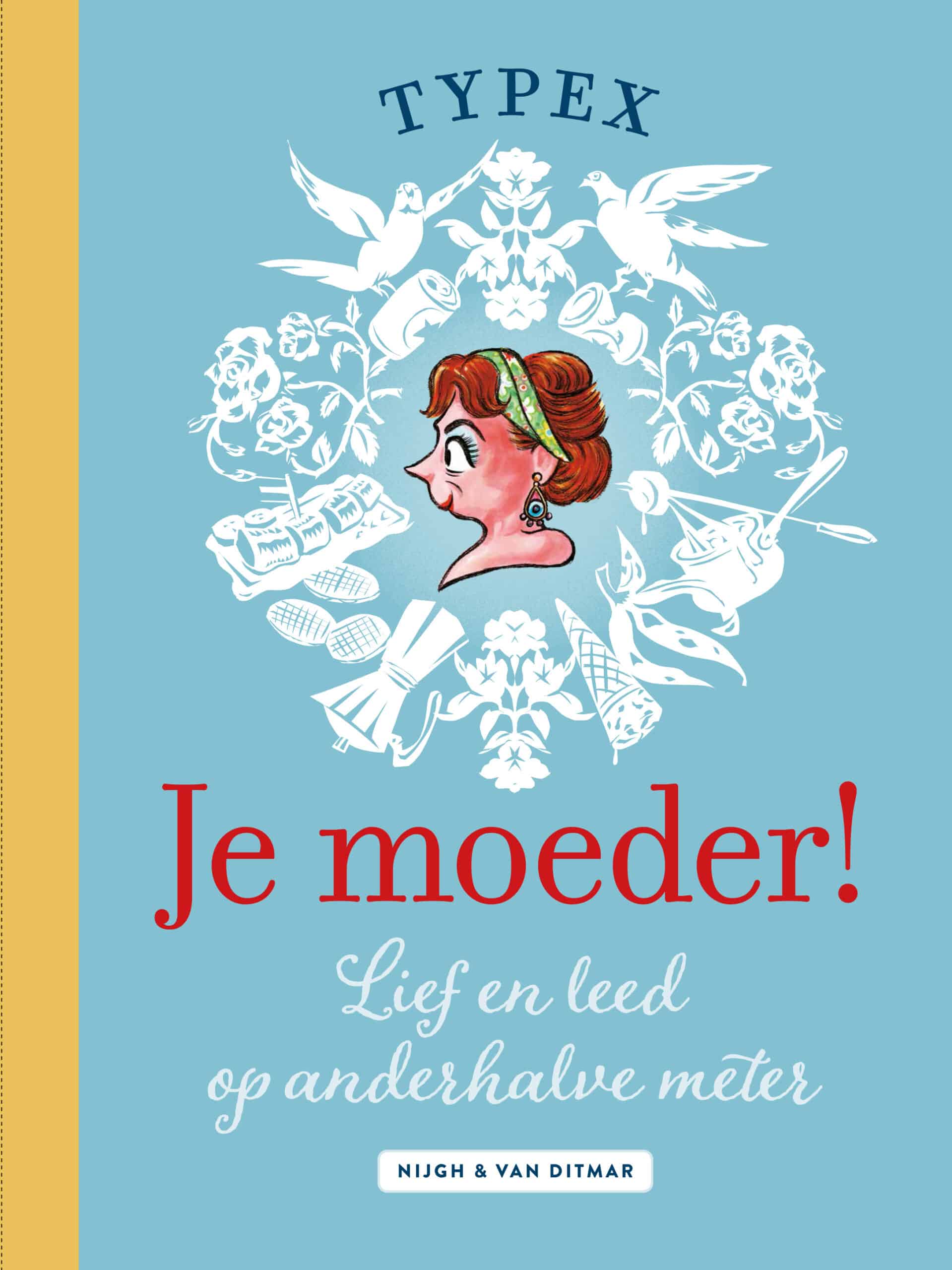

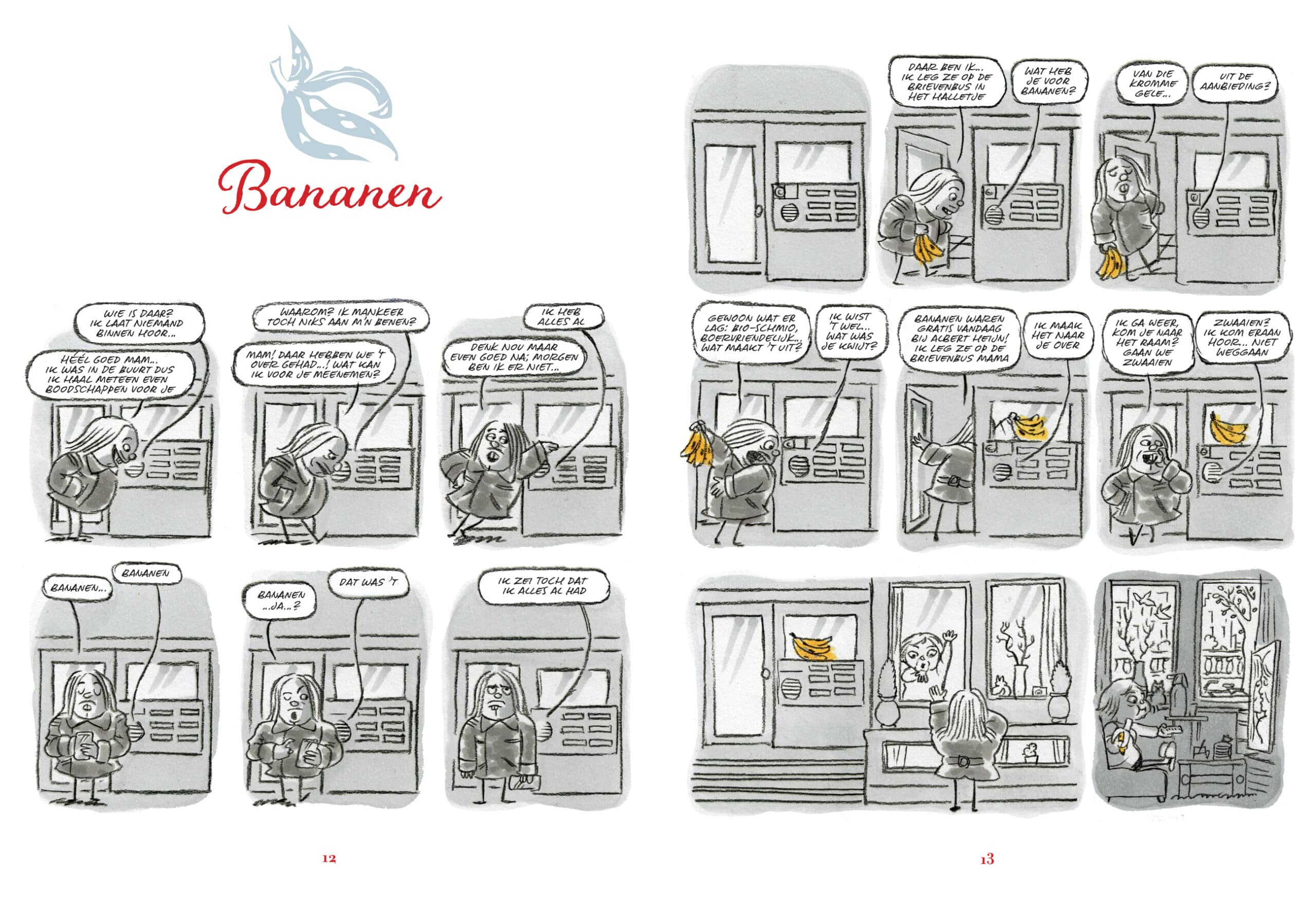

Stories continue to fascinate and stimulate him. For instance, for half a year he narrated the effects of coronavirus on his mother, younger brother and himself in de Volkskrant. The gently cartoonesque tranches de vie

were collected to make Je moeder! (Your mother!), which was published in February 2021 by Nijgh & Van Ditmar. Depicting life as it is in times of coronavirus, with all their everyday highs and lows. Typex presents himself and his family recognisably but in strikingly simplified form. The cartoons are almost literal transcriptions of the interaction between mother and sons, without frills or pretence. Relatable, funny and also comforting for a great many readers.

Rumpelstiltskin

Typex’ oeuvre reveals his immense graphic skill – in particular the two biographies bear witness to the enormous appetite, drive and indefatigability of this author in delivering layered stories, on a grand scale and with boundless ambition. After all, not everyone would dare to make a start on canonised figures from art history of Rembrandt and Warhol’s calibre. It demands unmistakable courage, perseverance and also – undoubtedly – the ability not to give a toss about the mass of facts, images and opinions to knead into new stories. And if something stands out, it’s the pleasure of producing a good story that jumps off the page, skilfully reinforced by all the elements the maker has at his disposal. In Typex’ Rembrandt that is the rusty, baroque interplay of lines that seem to flow from the Dutch master’s pens and brushes. In Typex’ Andy, as described, each chapter breathes a visually different atmosphere, with different fonts and often also psychedelic colours. Typex is a graphic chameleon, that’s for sure.

Drawings from 'Your mother'

Drawings from 'Your mother'© Nijgh & Van Ditmar

The cartoon medium offers a certain advantage to his manner of working. The American cartoonist Art Spiegelman, famous for his award-winning Holocaust epic Maus, once said of himself and his peers, ‘We fly below the critical radar.’ Typex affirms that: ‘I’m immensely fond of the cartoon medium. It’s something grand, the possibilities are unprecedented. It’s actually nice that not everyone knows we’re called Rumpelstiltskin. That the cartoon isn’t yet as well-trodden a path as film, for instance.’

In any case the Rumpelstiltskin known as Typex has not yet finished telling his story.