The library is experiencing a revival. Where in recent years more and more libraries have closed, today the public institution presents itself as the number one place to acquire knowledge and meet others. How exactly do these ‘living rooms of towns and villages’ look? And are there differences between the Netherlands and Flanders?

Once upon a time libraries were places of silence. Anyone who made a noise was called to order by a stamp-wielding librarian behind a desk. Returning a book late resulted in eye-watering fines and the majority of the novels on the shelves looked seriously aged.

Or at least, that’s the image many Flemish and Dutch people report when you ask about the realm of the library. But those who retain this kind of impression have missed some important developments in recent years. We now find the desk staffed by young people, fines are increasingly being written off and the collections are looking fresh.

Exhibitions and coffee

One of the libraries where this transformation has taken place is De Krook in Ghent. Since 2017, a sleek, modernist building has adorned the city centre, boasting multiple floors of books, reading areas, exhibitions and even its own café. The library has been embraced by young and old as a place where people can go, not only to pick up a book but also to stay and hang out for hours at a time.

Nevertheless De Krook is really a fairly classic library, director Krist Biebauw admits. This flagship of Ghent’s library network, which boasts another fourteen local district branches, still focuses mainly on the book: shelves of fiction and nonfiction take up a large proportion of the space. The collections, however, are composed “in response to demand from citizens”, Biebauw explains. “The diversity of Ghent’s population continues to grow. Our shelves increasingly reflect multilingualism.”

De Krook library in Ghent boasts multiple floors of books, reading areas, exhibitions and even its own café.

De Krook library in Ghent boasts multiple floors of books, reading areas, exhibitions and even its own café.© City of Ghent

We shouldn’t forget De Krook’s peripheral programming either. The library acts as a platform for all kinds of activities, such as lectures and courses, organised by the city and its residents. All these activities still fit in with the mission of the library as it has existed for more than a century: edification of the populace. Although these days, Biebauw notes, we tend to express it differently. “We want to help people better understand today’s world.”

Technological challenges

That world is currently also to a large extent a digital one. For that reason the library uses its information desks and appointments to assist people in their contact with digital administration. University research groups are also located at De Krook, tackling the greatest technological challenges of our time, such as acquisition of digital skills and deployment of robots in the care sector.

Does all this really belong in the library? Biebauw has no doubt about it. “It still feels like you’re walking around in a library here. We’re addressing social issues, ideally with our collection to hand. And we help people to acquire knowledge by offering an environment in which they can concentrate.”

It works: increasing numbers of young people alight with their textbooks in the public library, where social pressure prevents them from looking at their phones as much, Biebauw has discovered from research. So technology nevertheless does come into play.

The comeback

De Krook is not the only library to have broadened its remit. Dutch law even established this extension in January 2015, in what is known as the Wet stelsel openbare bibliotheekvoorzieningen (Wsob), the Public Library Facilities Act, which states that the library is not only responsible for a collection, but also for the associated promotion of reading, facilitating meetings, organising debates and more.

© Pixabay

That was the impetus for the library’s comeback. The institution was even mentioned in the King’s speech in 2023, when he explained how the budgets would be allocated in 2024. From 2024, millions of euros will be freed up to restore the library network to full coverage of the country, to renovate institutions and to keep them open for longer.

Such financial revival cannot yet be seen in Belgium, Biebauw has to admit. “After years and years of cuts, the Dutch library is on the up again. In Flanders the legislation we’ve had on libraries since the 1970s has in fact disappeared, and with it the duty of local authorities to ensure comprehensive library facilities.”

What also hasn’t helped is the complex Belgian – and therefore also Flemish – system. “There may be an overarching national library [the KBR in Brussels, AvdD], but it has no authority over public libraries because they are locally managed and funded,” Biebauw notes. “That’s a substantial difference from the Dutch situation. In the Netherlands the KB, the national library, has in fact grown stronger since the introduction of the Wsob: for instance it provides a national network of digital information points, school libraries and digital citizenship facilities.”

Our world is increasingly a digital one, which is why the library also provides space for digilabs.

Our world is increasingly a digital one, which is why the library also provides space for digilabs.© Laura Siliquini / LocHal Tilburg

Money for e-books

That digital offering is also rather better organised in the Netherlands. The KB there runs a large-scale e-book platform that can be used by all members of Dutch libraries. In Flanders there is a similar service, but publishers there are rather more reluctant to provide rights to digital copies. “In the Netherlands the government has provided a pot of money to make this transaction more attractive to publishers,” Biebauw observes. “Of course the target market in Flanders is also smaller: we only have six million potential readers, whereas the Dutch market has 18 million. This impedes the development of a high-quality product.”

There is additional difficulty in the Flemish situation because the library landscape is so fragmented. Where the Netherlands underwent a significant shift towards larger library organisations around the turn of the millennium, in Flanders each local authority has its own library. The average target market is therefore between 10,000 and 30,000 residents, compared with more than 100,000 in the Netherlands.

Where the Netherlands underwent a significant shift towards larger library organisations, in Flanders each local authority has its own library

Nevertheless Mark Deckers, one of the Netherlands’ foremost library experts, known in part for his blog markdeckers.net, where he regularly analyses library trends, believes that not everything is less well organised in Flanders. “In the Netherlands we haven’t yet managed to implement a central library system; in Flanders, despite fragmented management, there is communal investment. Subscription fees in Flanders are also much lower: thanks to a substantial government subsidy the cost to the citizen is often as little as 10 euros a year, whereas in the Netherlands you can easily spend 50 euros. In Flanders there is more of a conviction that the library is a basic service to which every citizen, regardless of means, should have access.”

Third space

Moreover Flemish and Dutch libraries largely focus on the same issues. “Both countries are re-evaluating the library and broadening its range of tasks. For a long time people were searching for the precise role of the library, but now everyone – from library to citizen – seems to have fully embraced their role as the living room of a village or town,” says Deckers.

In Belgium less money is freed up for that than in the Netherlands. That may be because the distress call around the decline in reading skills among young people is growing ever louder in the Netherlands. International studies among Dutch secondary school pupils reveal shocking scores in language acquisition, and when it comes to deriving pleasure from reading.

Reading at De Krook library in Ghent.

Reading at De Krook library in Ghent.© City of Ghent

“Libraries are trying to turn that tide,” says Deckers. “They’re not doing that on their own, but striking up partnerships with other institutions such as nurseries, primary and secondary schools and vocational colleges. They’re working together throughout the Netherlands based on nationally designed programmes. A good collection plays an important role, as does a teacher with expertise, a strong underlying policy, inspiring activities and guidance from the library.”

In recent years, in short, the library has been allocated a number of clear tasks: improving literacy and offering education and support in digital skills. In the Netherlands, these tasks are laid down in dedicated legislation; in Flanders, policy documents repeatedly refer to libraries as part of the solution to the above issues – unfortunately without linking budgets to them.

Library expert Mark Deckers: 'The library is one of the last public spaces where you don’t have to pay for entry or obligatory consumption'

Deckers feels that offering a low-threshold space for citizens to spend time undisturbed is part of their remit. “The library is one of the last public spaces where you don’t have to pay for entry or obligatory consumption. That function of a third space, where different demographic groups can encounter one another is ever more important in this era of increasing polarisation.”

Sitting ducks

Not everyone is as enthusiastic about the library’s new trajectory. Jan Van Herreweghe, alias Jan Bib, has worked for more than 40 years in different Flemish libraries and is not afraid to speak his mind. “The disappearance of Flemish legislation around libraries has turned them into sitting ducks when it comes to budget cuts. No inspector comes round to check whether everything is going well. There were once all kinds of standards as to the minimum number of books you had to have per institution, now there’s nothing like that.”

The content of library collections is also suffering as a result. Since retiring two years ago, Van Herreweghe sometimes checks the catalogues of 20 Flemish libraries, purely out of interest, to see what they have. “It’s a sad state of affairs. Budgets have been drastically reduced and the people who once purchased books are retiring and not being replaced. Or they’re replaced by someone with no training, who has no idea what a good collection entails.”

Former librarian Jan Van Herreweghe: 'The disappearance of Flemish legislation around libraries has turned them into sitting ducks when it comes to budget cuts'

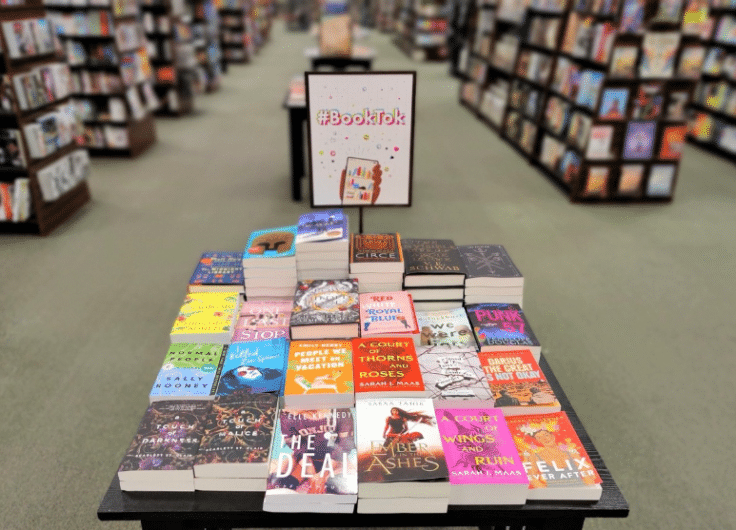

The downward spiral in the quality of Flemish and Dutch literature production also doesn’t help, in Van Herreweghe’s view. “At the moment it’s mainly English-language fantasy that’s the order of the day. Of course all forms of reading should be encouraged, but these trends come at the cost of literature in Dutch. Even secondary schools barely make space for reading. I see it in my adolescent daughter: we have more than 14,000 books, but she doesn’t read a word.”

LocHal in Tilburg, once a building in which trains were restored, now a library

LocHal in Tilburg, once a building in which trains were restored, now a library© Ossip Architectuurfotografie

Post offices and prisons

Van Herreweghe is more optimistic about Dutch libraries. He mentions LocHal in Tilburg as a shining example, a monumental building in which trains were restored, and which for some years has served as one of the showpieces of the Dutch library network. The Netherlands does have more recently built or refurbished libraries, and it is notable how often buildings with a long history take on a completely new function in the process. Other examples include the library in Leeuwarden, housed in a former prison and the central library in Schiedam, in the former corn exchange. The headquarters of the Bibliotheek Utrecht is yet another case in point: for the last couple of years it has been housed in the former post office. After a long drawn-out period of renovation that kept on running into difficulties, within a week the signatures were obtained to accommodate the library in this historic building that in its previous life also played a major role in sharing knowledge and facilitating meetings.

That’s precisely what Utrecht’s library stands for today, explains director Deirdre Carasso. A few years ago she made the move from museums to the library sector, bringing along her experience of collaborating with local authorities. “There’s room for the library to become more of a place where citizens not only acquire knowledge, but also share what they know. The challenges facing society today are too great to be solved from a single perspective, that’s my conviction.”

The Utrecht library houses in a former post office.

The Utrecht library houses in a former post office.© Bibliotheek Utrecht

Hip hop and Japanese

This way of working has increasingly become part of the DNA of the library, in Utrecht too, where collections and programmes are developed in collaboration with many different communities. For instance there are readings in different languages and the Japanese collection is supplied by citizens themselves. Recently the HiphopHuis also opened, a collection composed in co-creation with the people of Utrecht.

Nevertheless this manner of thinking is in no way new, Carasso emphasises. “Many libraries, in Utrecht as well, were founded by private individuals. Our collection has always taken multiple forms, with collections from a range of different fields: from fiction to non-fiction, from science to psychology.”

Do citizens really expect such close involvement? Carasso doesn’t doubt it. “Of course we need to explicitly invite people in. Initially they’re sometimes a little reticent, but in the end curiosity wins out. Our approach appeals to the need to belong. The library is a place for sharing, not only books or space, but also knowledge and stories. That’s our future.”