Tournai: A Musical Crossroad in the 14th Century

In the late Middle Ages, the city of Tournai, located on the border of France and Flanders, saw an infusion of wealth that resulted in a vibrant musical and literary culture under the patronage of merchants, members of the aristocracy, and prominent ecclesiastical and monastic communities. Within this system, musicians who worked for churches and courts in the region moved freely back and forth between France and Flanders. Their movement fostered artistic exchanges that surpassed political, religious, and social boundaries leading to the creation of new poetic and musical styles.

The city of Tournai has long been of interest to musicians and scholars of the arts for its role in this rich cultural landscape during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Tournai Cathedral is well-known to music historians as home to the first multi-voice (polyphonic) mass compilation known to exist, commonly called the “Tournai Mass.” Beyond the cathedral, the city of Tournai enjoyed a rich and very public musical culture in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

The Cathedral of Our Lady in Tournai is well-known to music historians as home to the first multi-voice (polyphonic) mass compilation known to exist, commonly called the “Tournai Mass.”

The Cathedral of Our Lady in Tournai is well-known to music historians as home to the first multi-voice (polyphonic) mass compilation known to exist, commonly called the “Tournai Mass.”© Photo by Jean-Pol Grandmont/Wikipedia CC BY 2.5

Instrumentalists from Tournai were among the most prominent musicians in France and the Low Countries, and references to their employment appear in documents from northern centers like Lille and Douai (1). Despite its reputation, we are now left with few documents recording the musical practices of the city. What does remain, however, paints an intriguing picture of how musicians and composers associated with ecclesiastical and monastic communities in the city were connected to an international network of musicians. These people moved freely between neighboring cities in both France and Flanders, such as Ghent, Kortrijk, Thérouanne, Douai, Lille, Tournai, Arras, and Cambrai, thus highlighting the porous nature of the border between the two kingdoms in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

This migration of musicians was facilitated by overlapping diocesan and dynastic borders, for during this time, the city of Tournai fell under the jurisdiction of two dioceses, Tournai and Cambrai. The Escaut river, which runs through the city center, served as a natural dividing line for both bishoprics. Institutions on the east bank were under Burgundian control in the diocese of Cambrai, and on the western side of the river (which is where the Cathedral of Our Lady sits) was the diocese of Tournai. Within the bishopric of Tournai, there were cities controlled by the counts of Flanders and later the Burgundian dukes (Ghent and Bruges), as well as those subject to the French crown (Tournai).

Musicians and composers associated with ecclesiastical and monastic communities in Tournai were connected to an international network of musicians

As a result of Tournai’s position at the crossroads of both kingdoms, before it came under Habsburg control in 1521 under Charles V, the bishops of Tournai were very politically and culturally active in both French and Flemish-Burgundian territories. For example, two bishops in the fifteenth century, Guillaume Fillastre and Ferry de Clugny, were both installed as chancellors of the royal Burgundian Order of the Golden Fleece, lauded for its patronage of music. Overall, as a major ecclesiastical institution and diocesan seat, Tournai Cathedral and the city at large had a high reputation for musical activity in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Surviving manuscripts

The role of Tournai as an international music center on the border of Flemish-Burgundian lands and France particularly in the fourteenth century has only recently been studied in detail (2). Many documents and manuscripts held in the State Archives of Tournai attesting to this were destroyed during World War II, but there are a number that still survive in the Tournai Cathedral Archives. The sources held in this collection show musical practices at Tournai to be very closely connected to those in the diocese of Cambrai. This, coupled with fourteenth-century literary and music texts mentioning famous musicians and poets in the area, points toward a vibrant artistic community in Tournai that was frequented by clergy and laymen who moved back and forth between Flemish-Burgundian and French cities.

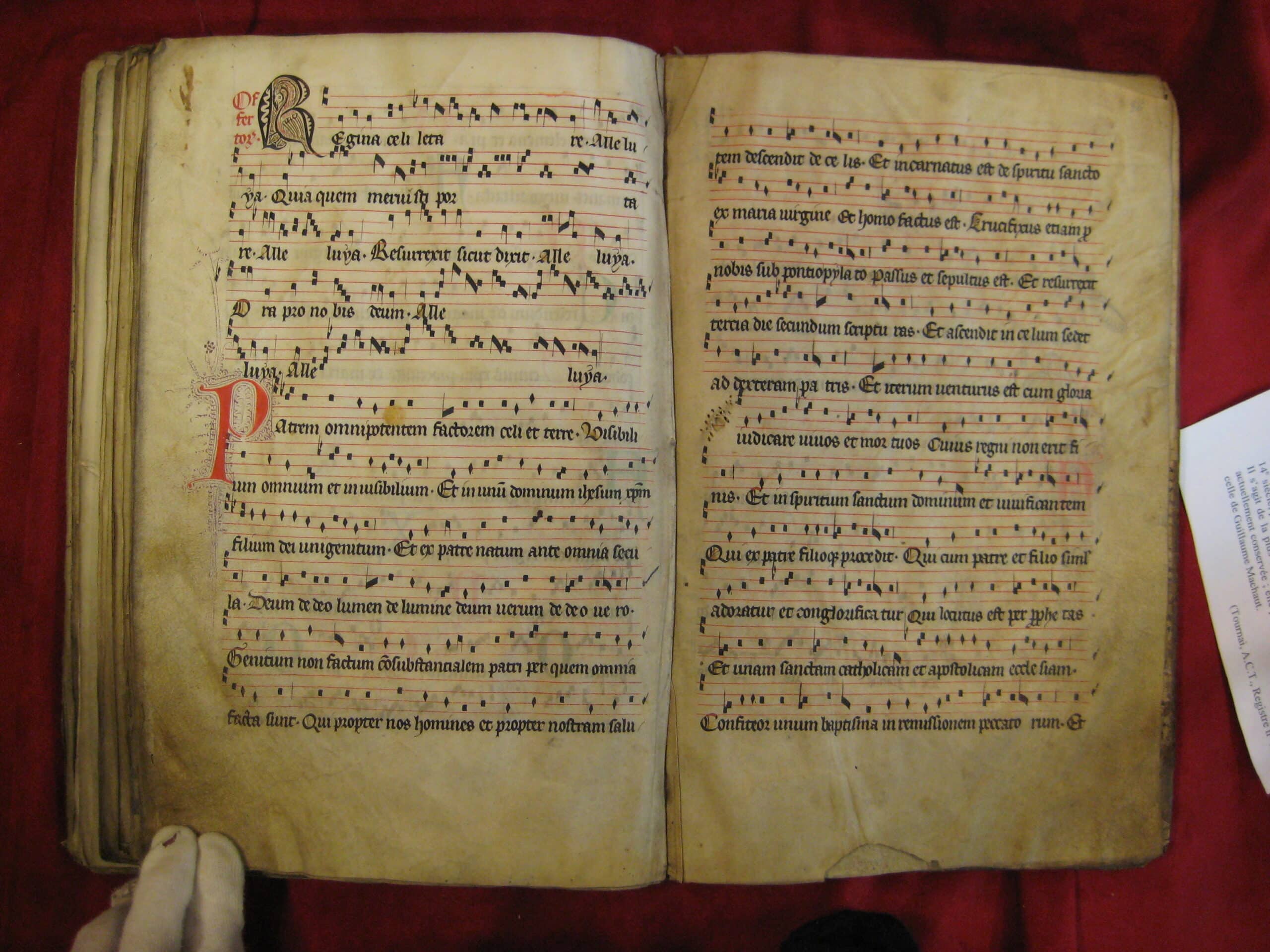

Pages taken from the manuscripts kept in the Tournai Cathedral Archives.

Pages taken from the manuscripts kept in the Tournai Cathedral Archives.© Tournai Cathedral Library, MS 27, folio 37v-38r

Among the witnesses to artistic contact specifically between the dioceses of Tournai and Cambrai are four manuscripts currently held in the Tournai Cathedral Archives. They are liturgical books containing plainchant and multi-voice musical settings (called “polyphony”) used by confraternities. Confraternities were important organizations that cultivated the composition of new music in the late medieval and Early Modern periods.

These communities would meet regularly for religious devotions, such as Masses and Offices (prayer services) featuring music in honor of a patron saint, holy figure, or relic; and they would hold banquets and take part in processions. Like guilds, some of them were organized around trades. Three of the books held at the Cathedral Archives were used by the Confraternity of the Episcopal Notaries, consisting of clerics and laymen in service to the bishop; and one book was used by the Confraternity of the Transfiguration, which was made up of priests and chaplains from Tournai Cathedral.

The contents of the manuscripts used by the Confraternity of the Episcopal Notaries mirror this organization’s international travels not only within Flemish-Burgundian lands, but far beyond. They include music for the masses and prayer services celebrated by this organization, and some of the chants and large multi-voice works show connections to those used at other churches in Flanders, the French court, and the papal chapel in Avignon. Notaries were professional scribes, whose job was to record all official acts and write up legal documents, so they were present at all proper events. In this capacity, Episcopal notaries moved frequently with the bishop, as they were an important part of his close entourage.

Besides bishop, poet and diplomat, Philippe de Vitry (1291 – 1361) was one of the most famous composers of his time.

Besides bishop, poet and diplomat, Philippe de Vitry (1291 – 1361) was one of the most famous composers of his time.© Wikipedia

As mentioned previously, the Tournai Bishops were very politically active in both France and Flanders. By the late fourteenth century, the bishops held prominent positions on the Burgundian ducal council, since two of the most prominent cities in the diocese, Ghent and Bruges, were under the rule of the Burgundian Dukes. They also travelled frequently to Paris since the city of Tournai was under the dominion of the French crown. The bishop’s notaries would have gone with him to these locations, ensuring their presence at major political functions where music was performed.

Some of these musical works, like the ones in the liturgical books discussed here, were used during the mass and prayer services. Others, like chansons and polyphonic multi-textual vocal works called “motets,” could have social and political overtones. Because of their frequent travels and appearance at religious and political events, notaries were optimally placed in a position to encounter both sacred and secular music and texts used outside of the diocese of Tournai.

Notaries as composers

Were the notaries bystanders on these occasions, or were they possibly involved in the creation of new music themselves? We have no direct evidence to answer this question, but if we look to other contexts, we find that there are several famous examples of notaries who were also composers – Philippe de Vitry and Guillaume de Machaut being the most well-known. These two individuals are among a long list of composers who were notaries in service to various French royal houses as well as the papal chapel in Rome.

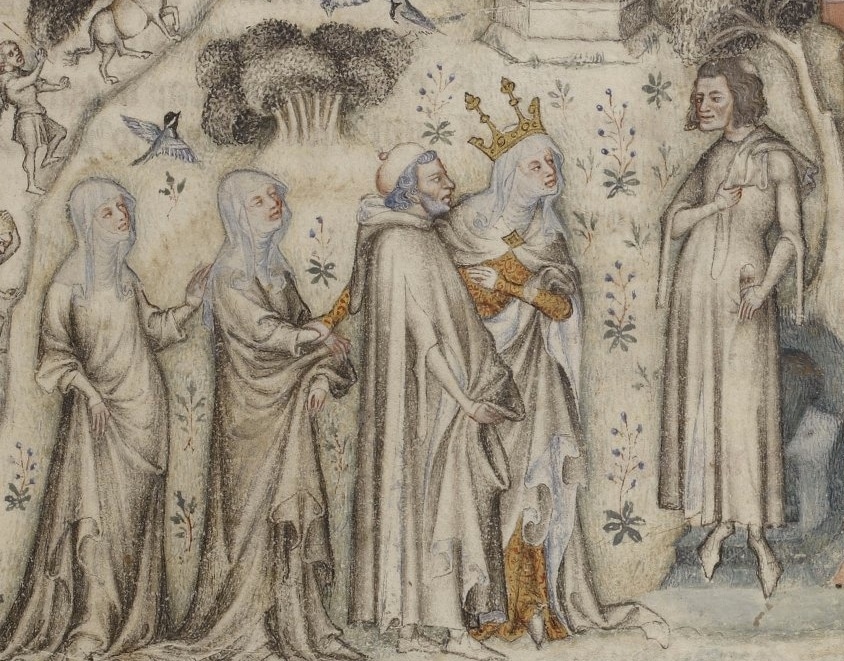

Notary and composer Guillaume de Machaut (right) as shown in an illuminated Parisian manuscript of the 1350s.

Notary and composer Guillaume de Machaut (right) as shown in an illuminated Parisian manuscript of the 1350s.© Wikipedia

Evidence of the musical output of notaries more broadly exists in the form of music notation in some of the documents they drafted (3). Furthermore, it was notaries who were responsible for the creation of the famous fourteenth-century Roman de Fauvel manuscript at the French court (Bibliothèque nationale de France, manuscript fr. 146), which contains many compositions by Vitry and others. Considering the known musical activities of notaries elsewhere, the Confraternity of the Episcopal Notaries in Tournai could have similarly included several men who were capable of composing chant and polyphony for their own services.

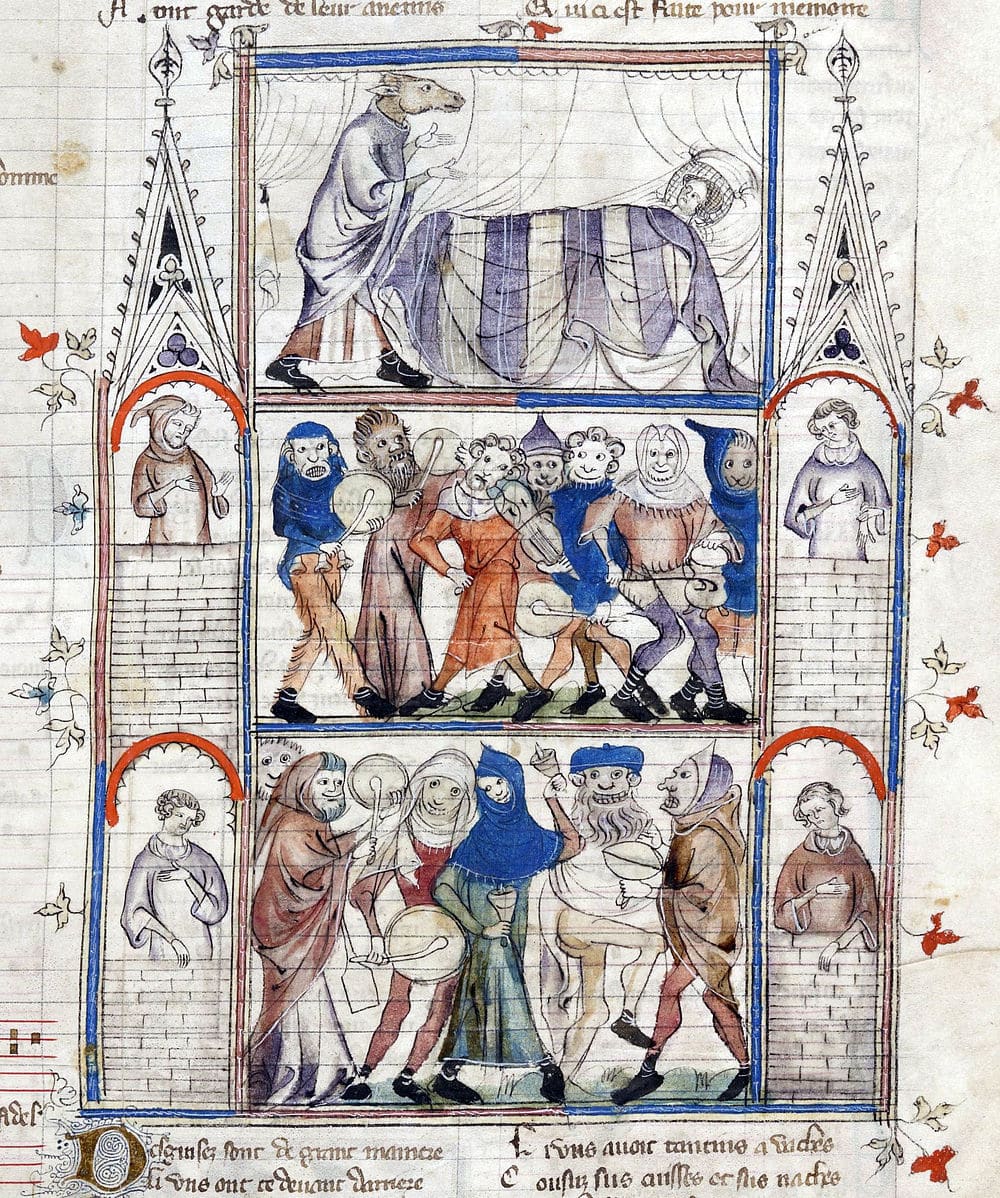

Notaries were responsible for the creation of the famous fourteenth-century Roman de Fauvel manuscript at the French court.

Notaries were responsible for the creation of the famous fourteenth-century Roman de Fauvel manuscript at the French court.© Wikimedia Commons / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Some of the most important organizations in northern France and the Low Countries in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that focused on the composition of new music and poetry were called puys, and they were known to have had notaries and members of the clergy among their ranks. Puys flourished in cities under Flemish and French rule, like Arras, Douai, Lille, Tournai, Valenciennes, and other urban centers in the dioceses of Cambrai and Tournai. These organizations often had a mixed membership of merchants, private citizens, members of the working class, clergy, monks, beguines, and nuns (4). There was a puy in Tournai in the fourteenth century, and it is possible that some notaries belonged to it.

Crossing borders

Against this historical backdrop, we can re-evaluate some of the contents of the manuscripts owned by the Confraternity of the Episcopal Notaries as being products of a network of composers who moved between France and Flanders, and who were associated with urban puys.

For example, there are two unique mass compositions that are found in one of the books (under the shelf number A 27), a Kyrie and a Sanctus notated as single voices in rhythmic notation, a method called cantus fractus. These two works were copied on the same pages in which we also find the “Tournai Mass,” mentioned above (5), but until now they have received very little attention.

The Kyrie and Sanctus are based on chant melodies found locally, strengthening the likelihood that they were local compositions (6). Furthermore, we know that these two pieces were performed as polyphonic canons, which was part of an improvised tradition that features compositional characteristics primarily associated with secular song, such as the French chace (7).

This discovery highlights the crossover between ecclesiastical and secular culture in fourteenth-century France and the Low Countries, opening numerous possibilities for investigating composers in the region of Tournai and their connections to other cities and communities in Flanders and beyond.

Several individuals from Tournai worked at various times in other cities within the diocese in the county of Flanders

If we look at it from this perspective, we see that there were indeed several individuals from the city of Tournai who worked at various times in other cities within the diocese in the county of Flanders, and who likely were associated with local puys and famous notary composers. These references come from local chronicles and from music texts.

In his Meditations of 1350, Gilles Li Muisis, abbot of the monastery of St. Martin in Tournai, praises the music and poetry of Philippe de Vitry (mentioned previously as a notary), Jehan de Le Mote, Jehan Campion, Guillaume de Machaut (also a notary), and Collart Haubiert. Both Campion and Li Muisis were based in Tournai, and Campion was associated with Vitry in various other contexts.

In addition to the chronicle, there is a polyphonic motet dating from around the same time, Appollinis eclipsatur-Zodiacum signis lustrantibus, which includes a list of composers from the north, calling them a “musicorum collegio.” It mentions several composers from Arras, Avignon, Cambrai, Douai, Tournai, and Valenciennes. Among them, we have Pierre de Brugis, who worked at Tournai cathedral, and Johannes de Ponte, who was a canon at the cathedral ca. 1330.

It is the career of Jehan Campion that best illustrates how these composers moved across dynastic borders and within both sacred and secular realms. Campion was a chaplain at Tournai cathedral in 1350 before he went on to the church of St. Donatian in Bruges, where he was elected chancellor in 1361. While at Tournai, Li Muisis and Campion were both part of a group centered around creating music and poetry, which can be called “an informal puy.” (8). Campion’s associates did not only include clergy and monks at neighboring monastic communities, but also laymen in the city of Tournai. An example is in the will of Peter de Melle, a citizen of Tournai, who left Campion several books of music and poetry upon this death.

Jehan Campion's importance lies in the fact that he is one of several people who moved in poetic circles that crossed diocesan, dynastic, and social boundaries

While we do have some of his poetry, we do not have any surviving music written by Campion, so there is no evidence that he would have composed the canonic Kyrie and Sanctus in the liturgical book owned by the Confraternity of the Episcopal Notaries. His importance lies in the fact that he is one of several people mentioned above who moved in poetic circles that crossed diocesan, dynastic, and social boundaries. The Episcopal notaries at the cathedral were also part of this clerical culture that had contact with such organizations, as we have seen with notaries elsewhere, and it is possible that some of them belonged to local puys.

In this respect, the unique compositions found in the notaries’ liturgical books could be viewed as part of Tournai’s artistic legacy that provided its professionals with multiple modalities with which to pursue and invest in music. These could range from composing the works themselves, to commissions, to bringing compositions back from their travels to other cities and courts.

These people had many ties to neighboring cities and were in some cases connected to artistic institutions that sat at the intersection of different social circles. Ultimately, this changes our focus from looking within the Cathedral walls for answers about local music composition in Tournai to looking outward, to nearby cities in France and the Low Countries.

References:

1) see Gretchen Peters, The Musical Sounds of Medieval French Cities, 2012

2) see Sarah Ann Long, Music, Liturgy, and Confraternity Devotions in Paris and Tournai, 1300-1550, 2021

3) see Barbara Haggh-Huglo, “Composers-Secretaries and Notaries of the Middle Ages and Renaissance: Did They Write?,” in Music, Space, Chord, Image, 2012.

4) see Brianne Dolce, “’Soit hom u feme’: New Evidence for Women Musicians and the Search for the ‘Women Trouvères’,” Revue de musicologie, 2020

5) facsimiles of these folios appear in the revised modern edition of the Tournai Mass by Jean Dumoulin, Michel Huglo, Philippe Mercier, and Jacques Pycke, 2016.

6) see Sarah Ann Long, Music, Liturgy, and Confraternity Devotions in Paris and Tournai, 1300-1550, 2021

7) see Jason Stoessel and Denis Collins, “New Light on the Mid-Fourteenth-Century Chace: Canons Hidden in the Tournai Manuscript,” Music Analysis, 2019

8) see Yolanda Plumley, The Art of Grafted Song: Citation and Allusion in the Age of Machaut, 2013