Banning, Preserving or Editing: What to Do with Offensive Books?

The judgment ‘offensive’ is inextricably intertwined with time and culture, the past another country. Nevertheless, it doesn’t follow that we should keep our hands off old texts, especially when it comes to children’s books. As the provocative exhibition ‘Offensive Books?’ at the House of the Book in The Hague shows, the written word is the ideal tool for planting pernicious ideologies in young minds.

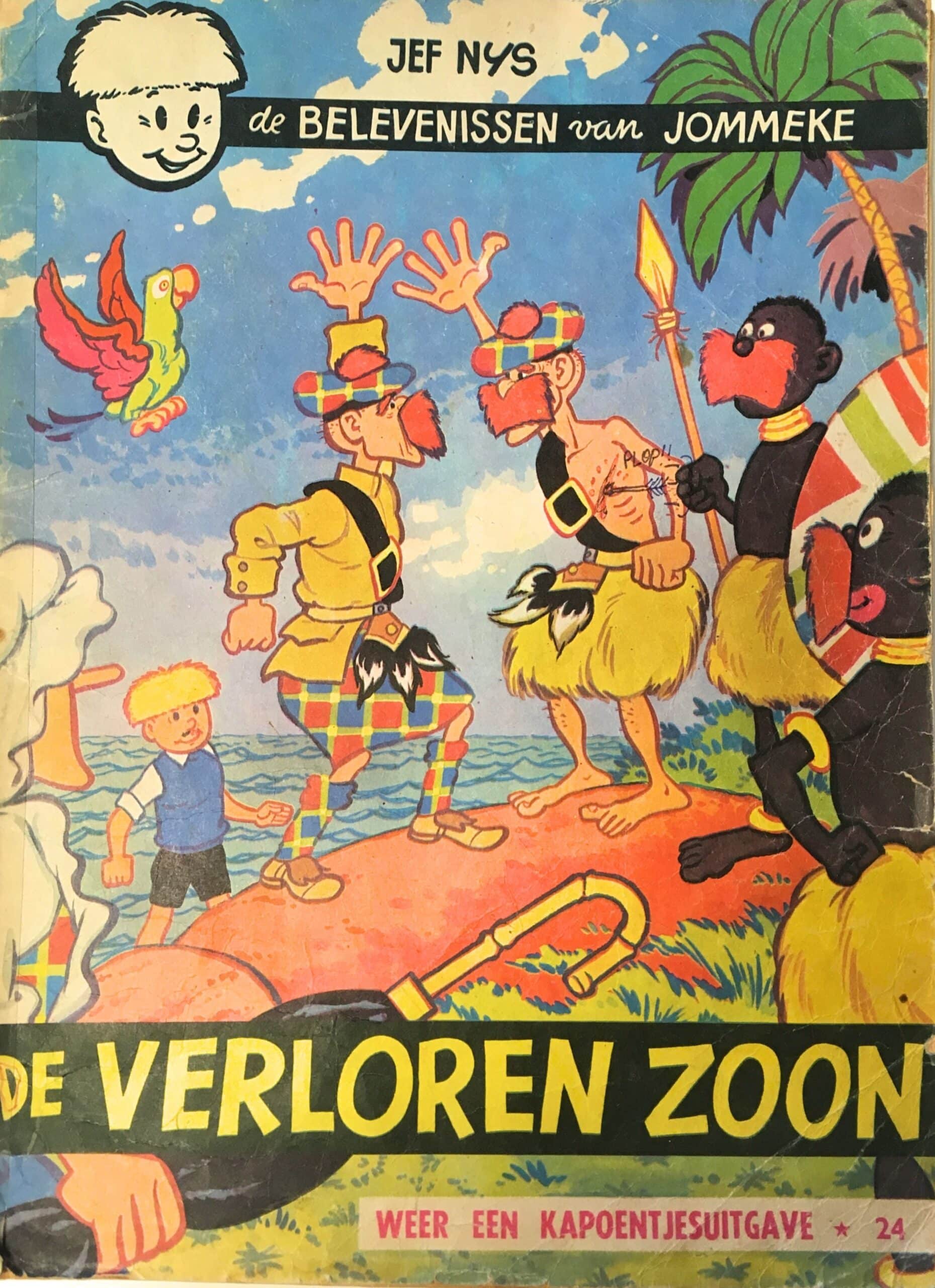

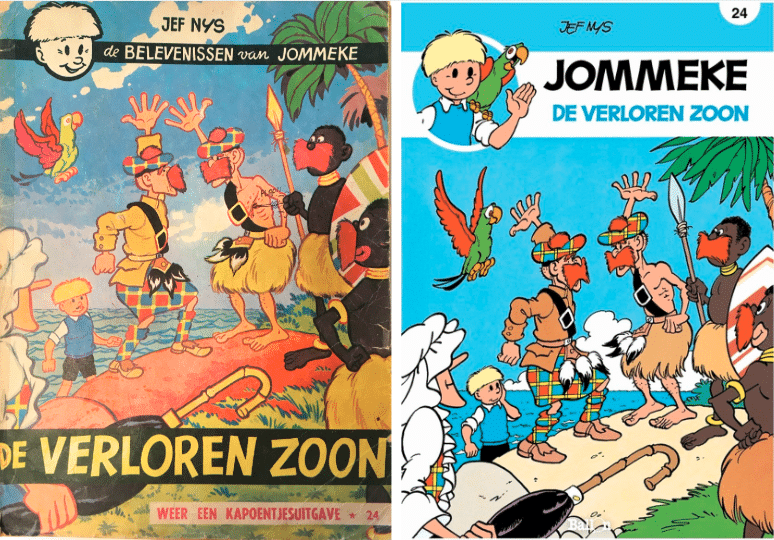

De verloren zoon (The Lost Son), a comic by Jef Nys from the series ‘De belevenissen van Jommeke’ (known in English as ‘The adventures of Jeremy’), is the only comic strip I still possess from my childhood. Evidently, I was so attached to it that I’ve kept it all these years. I must have read it around the age of ten. When my daughter reached the same age, I passed the battered 15-franc Kapoentjes edition on to her. And I came to regret it.

De verloren zoon (The Lost Son), Jef Nys, 1965

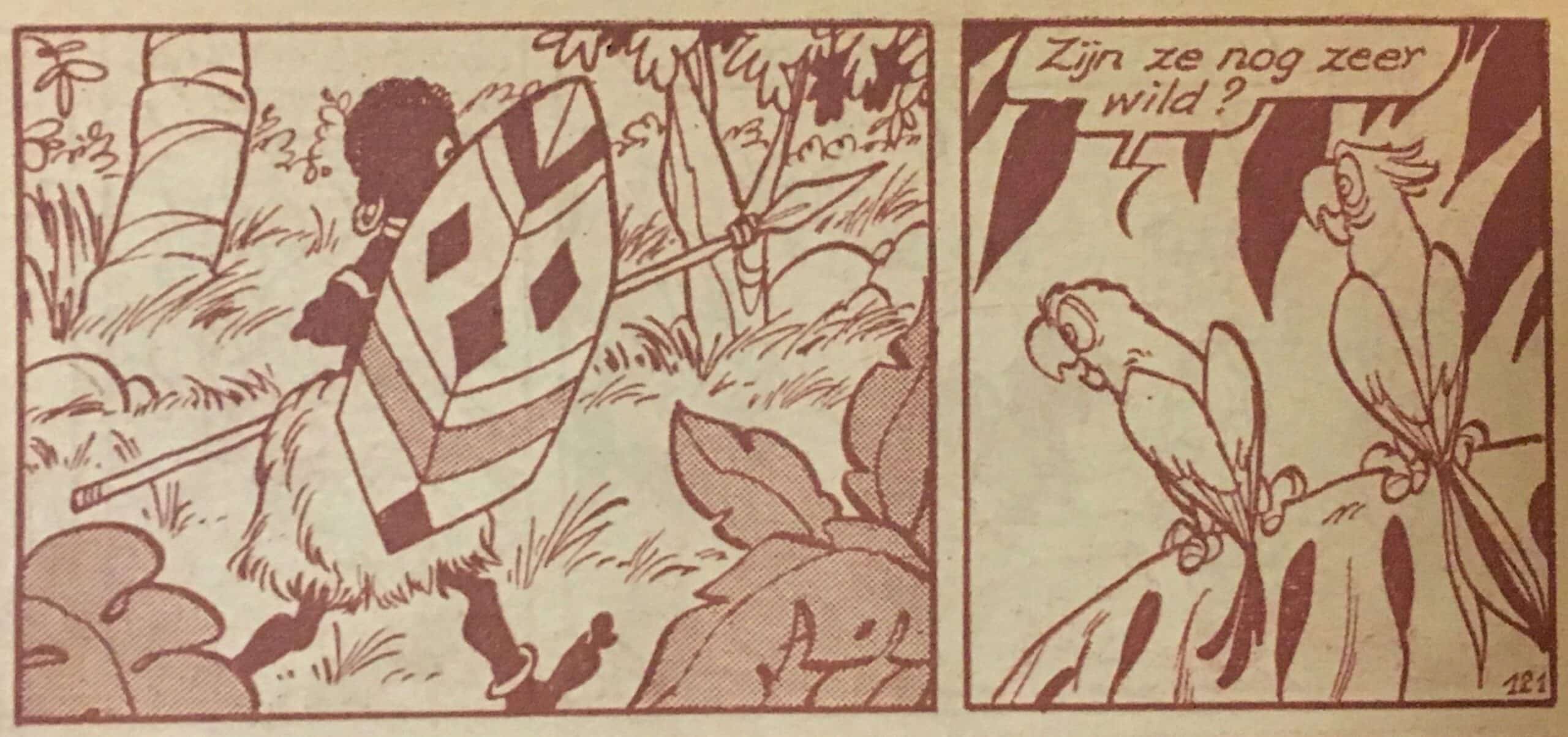

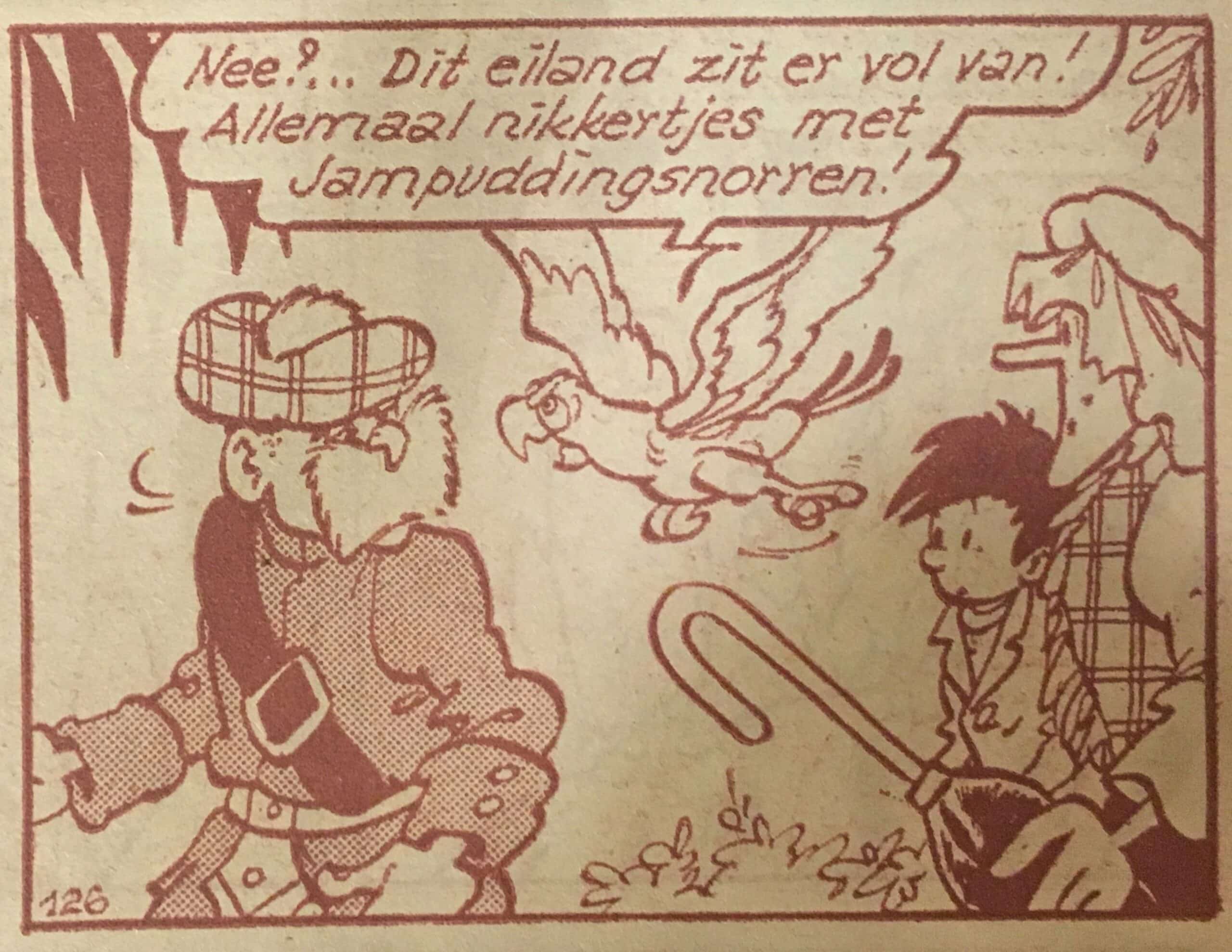

De verloren zoon (The Lost Son), Jef Nys, 1965She read the story. An ancestor of Mic Mac Jampudding, a Scot adorned with a red moustache, once sent his son to far-off lands to found a branch of the Jampudding clan. Jommeke and Mic Mac go in search of the descendants of this son. After lots of adventures his talking parrot Flip strikes up a conversation on an island with one of his kind. When he sees a local inhabitant with a spear and shield, he asks, ‘Are they still very wild?’ The other parrot replies that they’re actually very civilised and have a fiery chock of hair under their noses. Flip brings the glad tidings to his fellow travellers: ‘This island is full of them! They’re all nikkertjes (little niggers)with Jampudding moustaches!’ At first Mic Mac Jampudding can’t believe his ears, but the white king of the island confirms the story. He washed up there five hundred years ago. ‘There were blacks. They saw me as a sort of white god.’ He was permitted to marry ‘the chief’s daughter’, had many (black) descendants and survived all those centuries himself thanks to drinking medicinal water. Their ancestor’s wish came true, says Jampudding. ‘But he’d have had a surprise when he saw all those zwartjes (little blacks),’ the other agrees.

‘Are they still very wild?’

‘Are they still very wild?’In the comic strip it’s the white man and the king who have brought civilisation to the island. Even the words by which the white people refer to the black characters – ‘nikkertjes’, ‘zwartjes’ – reveal an embarrassing sense of superiority.

My daughter, who comes from Rwanda, soon put De verloren zoon down. She didn’t like it, she said. Out of curiosity, I reread the comic. I quickly saw why she hadn’t derived any pleasure from it, and I blushed with shame. That the cover hadn’t been enough to alert me. That the plainly racist nature of the thing had clearly been lost on me at the time. That I’d apparently found it a funny comic.

‘No? This island is full of them! They’re all nikkertjes (little niggers) with Jampudding moustaches!’

‘No? This island is full of them! They’re all nikkertjes (little niggers) with Jampudding moustaches!’Dark-skinned children do stupid things

The House of the Book in The Hague has dedicated a provocative exhibition to books which ‘due to a changed Zeitgeist and progressive insights have become controversial’: ‘Offensive Books?’ is set to run until 1 March 2020. Curator Bert Sliggers didn’t want to pre-empt visitors’ judgments and solutions, but rather to get them thinking. What do we consider offensive, what inoffensive, and why? Is it a reason to intervene in texts that are now considered outdated, or to ban them completely?

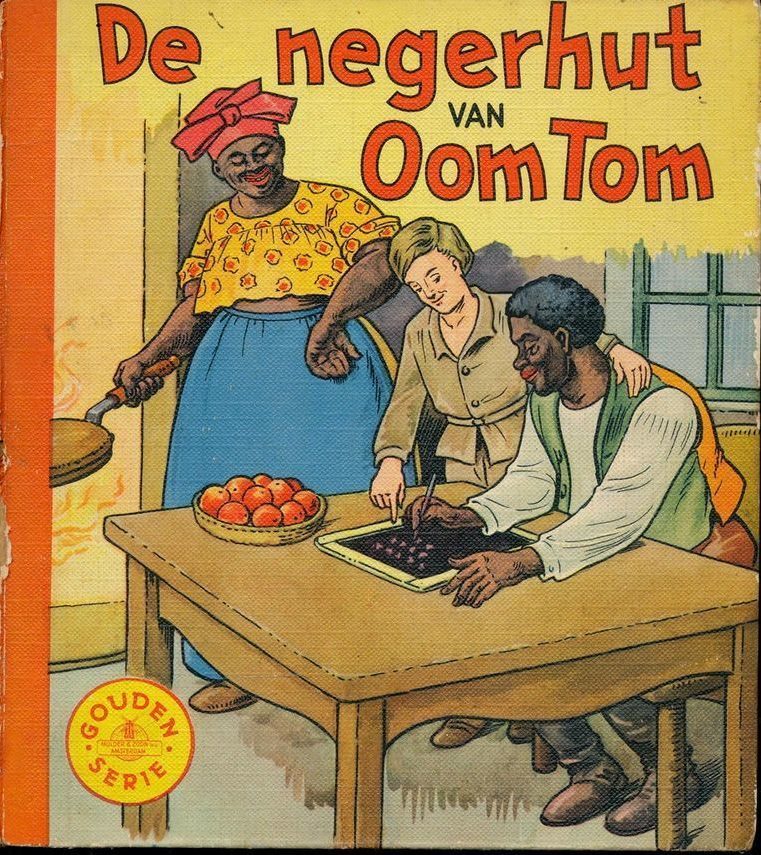

De negerhut van Oom (Uncle Tom’s Cabin), Harriet Beecher Stowe, 1852

De negerhut van Oom (Uncle Tom’s Cabin), Harriet Beecher Stowe, 1852De verloren zoon doesn’t appear in the exhibition, but it does have some similar examples to offer, revealing how widespread racist stereotypes were in children’s books that still enjoyed great popularity in my childhood. An explanatory text suggests that this was, ‘because the dark children who appeared in them often did silly things. They never learned and kept making mistakes.’ Revelling in the (presumed) silliness of another was and remains an ego-boosting activity.

What I found most disconcerting was the explanation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe, a book which, when I devoured it as a child, I saw as a good book. I still remember going to my parents filled with indignation at the fact that such a thing as slavery had existed. But what I didn’t see is that the book isn’t particularly free of racist stereotypes. There’s a reason why ‘Uncle Tom’ has become an insulting name for a black person who behaves subserviently towards a white person presumed to be superior.

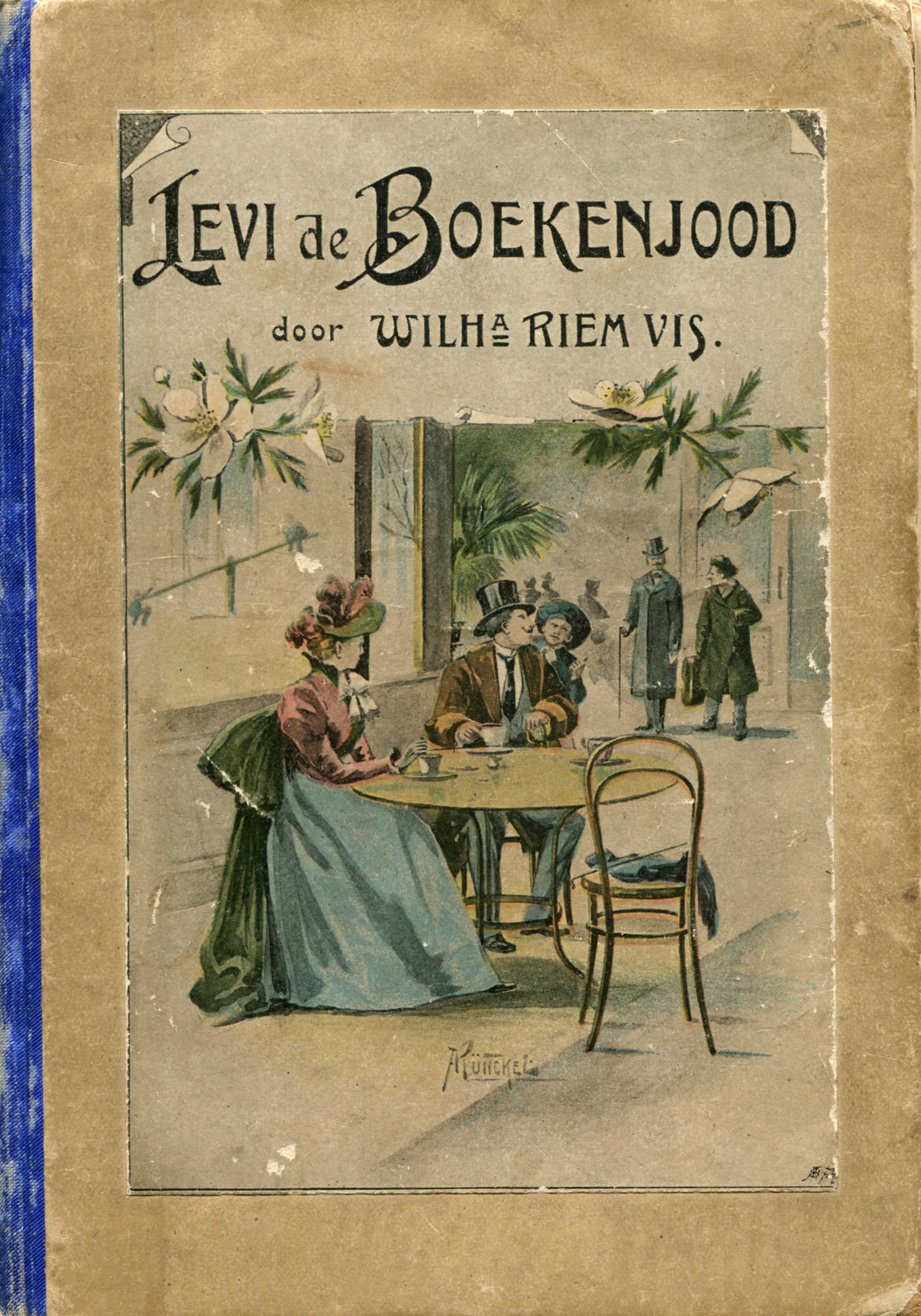

Levi, de boekenjood (Levi the book Jew), Wilhelmina Riem Vis, 1907

Levi, de boekenjood (Levi the book Jew), Wilhelmina Riem Vis, 1907Similarly chilling is the anti-Semitic propaganda on display at the House of the Book. In many children’s books such as Levi, de boekenjood (Levi the Book Jew), Jewish people come into contact with Christianity. They want to convert but are treated violently and rejected for that reason by the Jewish community. An embarrassing example is the story Van een jodenjongetje (About a Little Jewish Boy) which appeared in a language textbook for Roman Catholic primary schools. A little Jewish boy accidentally walks into a church and goes to communion. When his father hears about it, he’s furious and throws him into a burning oven. More than 350,000 copies of the book were printed between 1935 and 1956. After World War II, distribution simply continued. Only in 1952 did any discussion arise. In a parliamentary debate the serving minister acknowledged that the story was ‘unsuitable for spiritual and moral education’. But he found a ban to be in conflict with the constitution, which ‘calls for respect for the choice of teaching resources’. When Godfried Bomans raised the issue again in 1956 on the front page of de Volkskrant, the House of Representatives reached a different conclusion. The story conflicted with the ban on instigating hate towards an ethnic group, enshrined in the Penal Code. At the start of 1957, the minister announced that the book would be taken off the market.

Janneke is so good at keeping house

Many a visitor will, like me, be dismayed that flagrant antisemitism remained a blight on Dutch children’s books and textbooks years after the Holocaust. For most people nowadays, this is a crystal-clear example of ‘offensive’ material. Although a few may maintain that prohibition is pointless or restricts freedom of expression, even they will probably agree that either the publisher continuing to publish the book or the teacher using it in class had a screw loose.

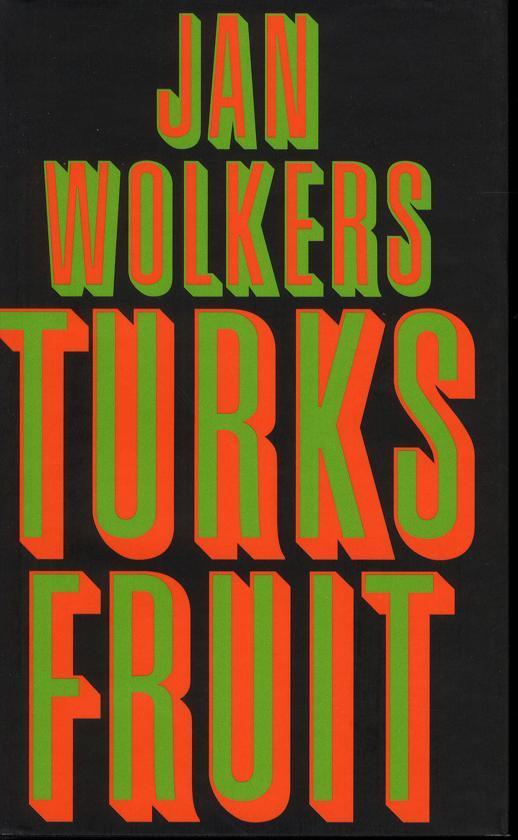

Turks fruit (Turkish Delight), Jan Wolkers, 1969

Turks fruit (Turkish Delight), Jan Wolkers, 1969But the less historical and cultural distance we have, the harder it is to make robust judgements. The section of the exhibition dedicated to ‘sexism’ highlights a quote from Jan Wolkers’ Turks fruit (Turkish Delight): ‘I screwed one girl after the other. I dragged them to my lair and tore the clothes off them and rammed myself silly. Then I hustled them out the door after a quick drink. Sometimes three a day. Big tits, sagging like sacks of porridge with rubber teats to suck on. Little wrinkly tits, too pitiful to pet. Better, in that case, to leave the sweater on.’ Wolkers is ‘simply sexist’ and should be removed from the canon of Dutch literature, is one standpoint. ‘Wolkers may be sexist, but he does write well. So he certainly can’t be omitted,’ is the judgement of another.

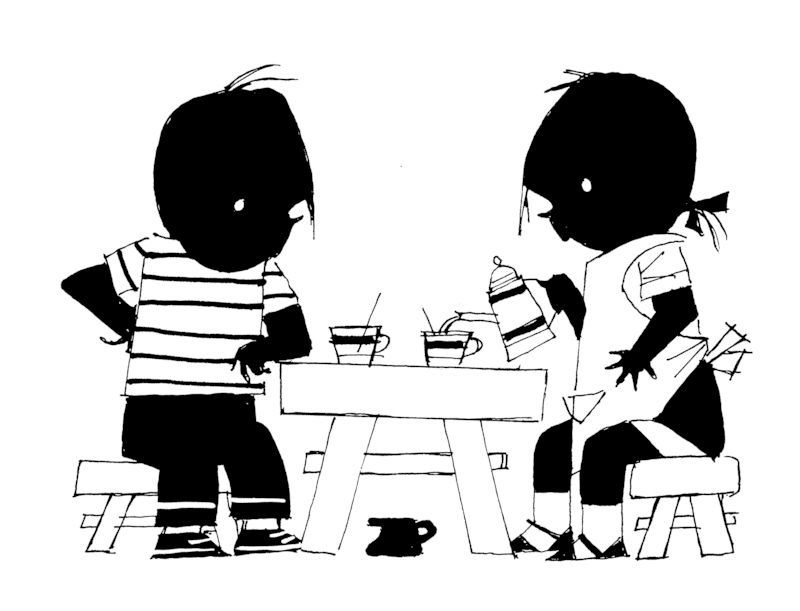

Or look at Jip and Janneke by Annie M.G. Schmidt. It is and remains an irrepressible classic that countless Dutch children have grown up with. But in Schmidt’s stories the division of roles between Jip and Janneke is traditional, to say the least. ‘Offensive books?’ highlights this passage from the story ‘Jip en Janneke gaan trouwen’ (Jip and Janneke get married).

‘When I grow up, Jip says, I’ll be an aviator. And what do you want to be, when you grow up?

I’ll be a mother, says Janneke.’

Jip and Janneke, Annie M.G. Schmidt

Jip and Janneke, Annie M.G. SchmidtIt’s certainly not the only story in which Schmidt – herself emancipated – displays somewhat traditional views on the division of labour between boys and girls. Another example is ‘Helping Mother’ from the fourth collection. Mother has been ill, the housework needs doing and she’s not fully back to work yet. ‘But nevermind. Janneke is home. And Janneke is so good at keeping house. She can do the dusting. And she can wash the windows, if necessary.’ Jip wants to help too. He starts vacuuming but soon sucks up the flowers.

Sex with a Doberman

Is this a problem? Should we have to accept these miserable traditional roles in Schmidt’s work, which remains so wonderfully, quintessentially Dutch? In the final room, visitors to the exhibition at the House of the Book can get to work and note their commentary in a number of dilemmas. In response to ‘Levi, de boekenjood in de boekenkast’ (Levi the book Jew in the bookcase), someone has written this heartfelt cry: ‘No way!!! Haven’t you learnt anything from history?? Preserve it in a dark place to show your grandchildren how strangely people can think, and tell the story of all those who died.’ In response to, ‘Remove books with stereotypical roles from the school library,’ someone has added, ‘No censorship please.’

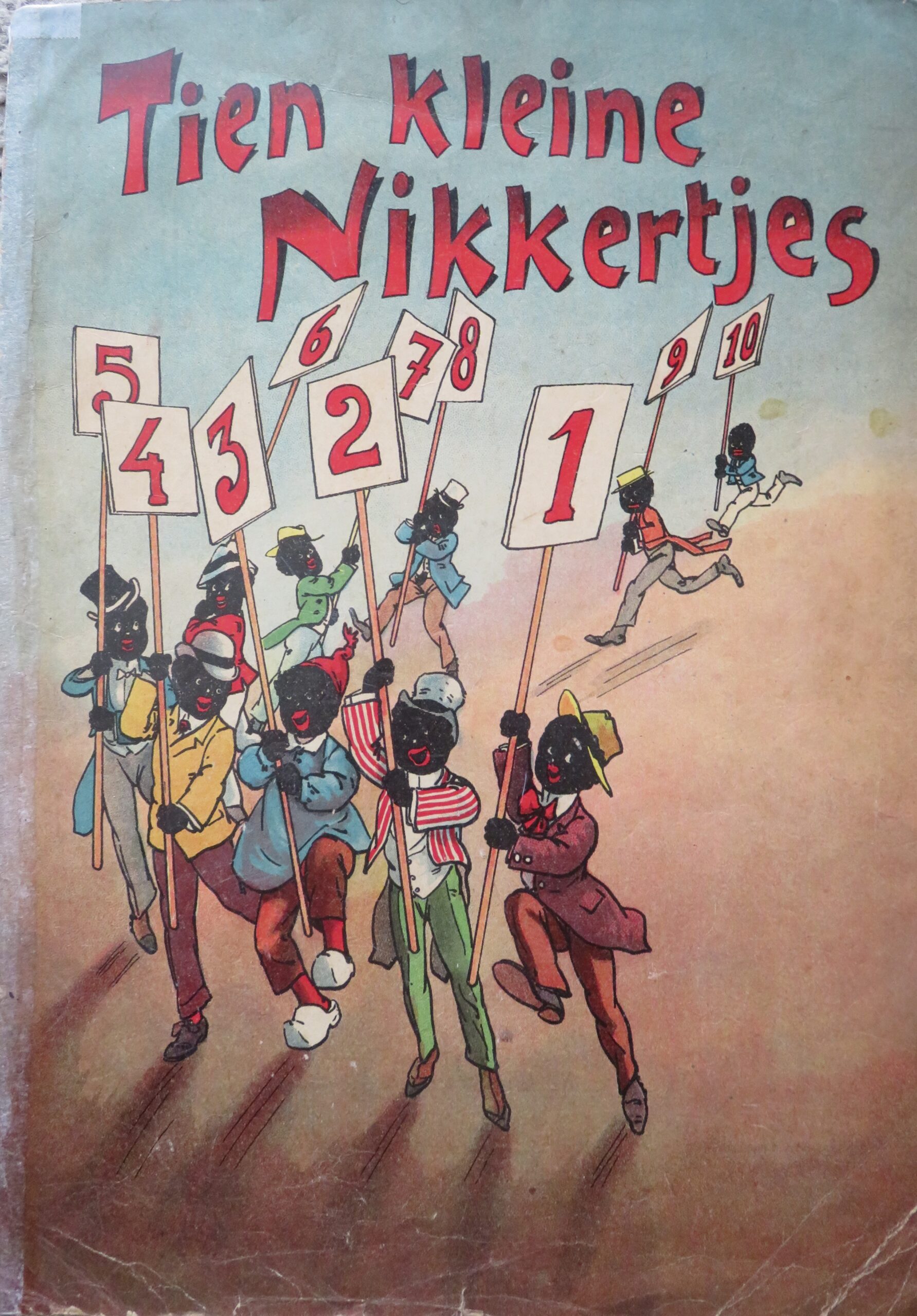

Tien kleine Nikkertjes (Ten Little Niggers), 1877

Tien kleine Nikkertjes (Ten Little Niggers), 1877These two opposing reactions may have more to do with different estimations of the seriousness of the problem. For most Dutch people, antisemitism falls into the category of ‘unforgivably offensive’, whereas they consider stereotypical roles to be at worst old-fashioned. Moreover, they see antisemitism as belonging to a different time or culture and count Jip and Janneke as part of their ‘own culture’.

From that viewpoint, it’s a shame that the only contemporary example of ‘offensive books’ that the exhibition displays in some detail is based on an ideology we can dismiss as coming from a different culture. The glass cabinets display the works of the Islamic preacher Abu Ameenah Bilal Philips. He is no longer allowed into the US, the UK or Germany, along with a list of other countries, due to his proclamation of extremist ideas, such as homosexuals deserving the death penalty and rape not existing within marriage.

Abu Ameenah Bilal Philips in 2010

Abu Ameenah Bilal Philips in 2010© photo by Muhammad Mahdi Karim

Most visitors to the exhibition, including myself, will not hesitate to categorise the works of this Salafi as ‘offensive’. But I wonder, are there contemporary books by writers and philosophers situated in the European cultural tradition that we can classify in this way?

If I may offer one myself: Le grand remplacement (The Great Replacement) by the ‘extreme-right house ideologist’ Renaud Camus. According to Camus’ conspiracy theory, Western elites want to replace the white population to destroy the nation-state and establish their dream of a global world order. In a more or less concealed form, such ideas are spread far and wide by Dries Van Langenhove, chair of the extreme-right youth movement Schild & Vrienden and MP for the Flemish nationalist party Vlaams Belang, and by the Dutch leader of the right-wing party Forum for Democracy Thierry Baudet.

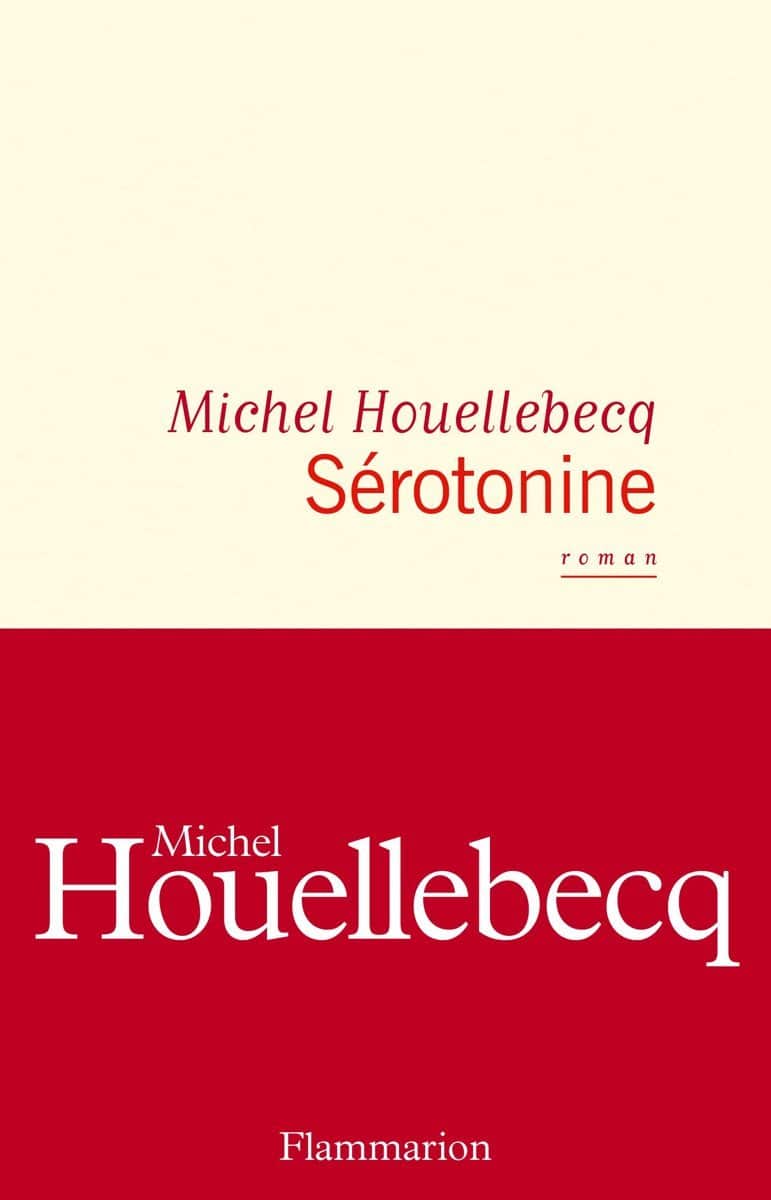

Sérotonine (Serotinin), 2019, Michel Houellebecq

Sérotonine (Serotinin), 2019, Michel HouellebecqAnother candidate: Serotonin by Michel Houellebecq. The main character (who shouldn’t be confused with the author) sees women as prostitutes. His misogyny reaches a nadir when he watches a video in which his lover has sex with a Doberman and a Bull Terrier, after which he is completely devoid of empathy for dogs. ‘What most surprises me might be the lack of criticism for his coarse sexism,’ wrote Cyrille Offermans in De Groene Amsterdammer. ‘If the infinitely more subtle Jan Wolkers, as recently became clear, had already been pilloried by MeToo, hasn’t the French provocateur

at least earned eternal damnation?’ Margot Dijkgraaf deemed his writing ‘intolerably negative about women’, but awarded the novel five stars in NRC Handelsblad. Does literary quality make up for unadulterated sexism? Is Houellebecq offensive or are we confusing him with his character? In a few decades will everyone be surprised that serious reviewers got away with it?

By raising such questions and also by displaying passages by a European author counted by many as a great contemporary writer, or by a politically influential thinker with controversial ideas, the creators could have intensified the debate. As it is, they’re playing it safe. It’s always the other, from a different time or tradition, that is offensive. But the real issue is recognising dangerous ideas brewing in our own society.

They want to rewrite everything!

Certainly, works from the past can be a rich source of controversy in the present. ‘The past is another country and if you view it through the lens of today’s values, it would be unacceptable to continue reading or performing anything,’ Mia Doornaert wrote recently. The columnist and chair of Flanders Literature snorted with indignation at the fact that there are currently people wanting to rewrite Shakespeare’s plays due to their presumed sexism and racism. In one and the same column, she stood up for freedom of expression for the plastic surgeon Jeff Hoeyberghs, who had garnered a storm of indignation with misogynist remarks. In Doornaert’s view, rewriting Shakespeare and the attempt to silence Hoeyberghs fitted the same pattern: the suppression of free expression and the belief that readers and listeners aren’t up to the job of withstanding presumed or actual sexism.

Doornaert of course is absolutely right that there’s no point in measuring historical characters and works of art by contemporary moral standards. That we should read them in the context of their era. That we should trust in the reader’s ability to take a critical stance towards the text they’re presented with. That it’s a crying shame to throw literary masterpieces in the bin or censor them because they don’t comply with our contemporary standards.

But what the exhibition in The Hague particularly reveals is that the clear and apparently convincing decree, ‘Hands off, no to bans or censorship!’ doesn’t stand up. Because the book, as the Nazis unfortunately proved, can be a ‘spiritual broadsword’, an extremely effective weapon for planting an ideology in people’s heads. Especially for children. The makers of ‘Offensive books?’ note that children’s books play a major role in spreading religions and ideologies. They can function as little indoctrination programmes, allowing dubious ideas to penetrate brains while they are still highly receptive.

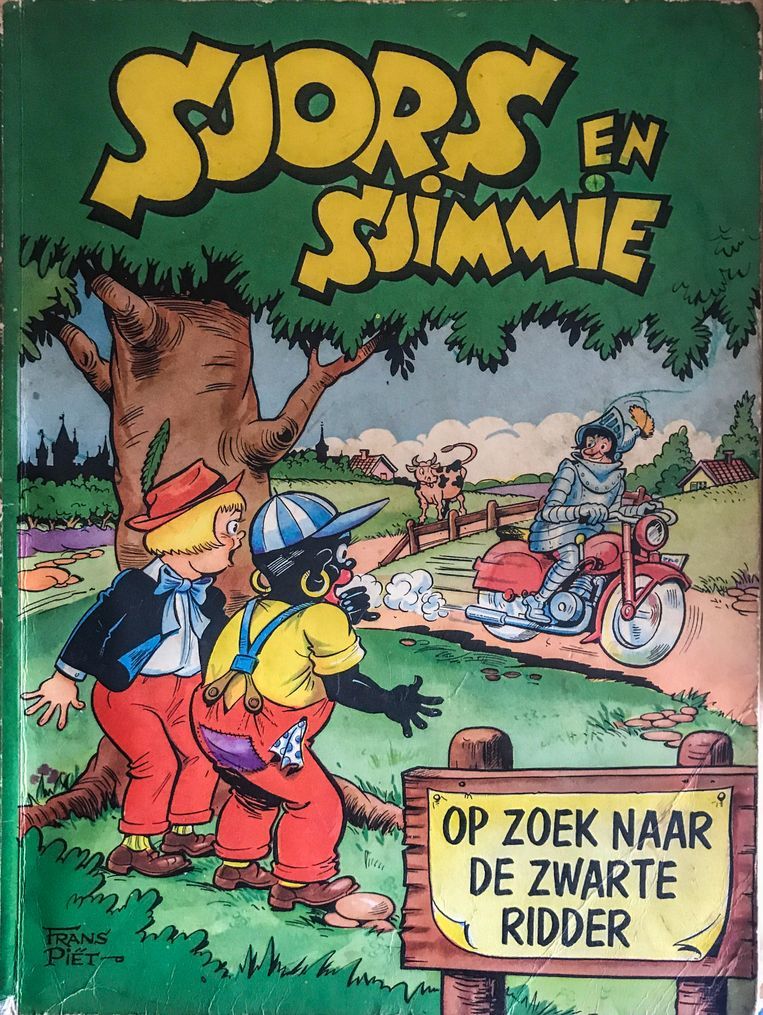

Sjors and Sjimmie, Frans Piët, 1959

Sjors and Sjimmie, Frans Piët, 1959Certainly, banning books that we consider offensive is very rarely a solution. Who should do that? A state committee of censors? The horror. But perhaps publishers, book shops and libraries can take their share of the responsibility. They determine what’s worth publishing and placing on the shelves. We can’t reasonably expect children to have fully developed their moral antennae for racism and sexism, sometimes in a concealed form, whereas it’s perfectly reasonable to expect that of adults whose job it is to publish and evaluate books.

Fortunately, publishers do take that responsibility. But it’s not easy, as illustrated by the latest edition of Jip and Janneke published in 2019. It has been revised, we read in the colophon. There is no explanation or account of the intervention. Comparative analysis shows that the language has been modernised here and there. For instance, the ‘aviator’ from ‘Jip en Janneke gaan trouwen’ has become a pilot. But it’s still Jip who wants to become that pilot and Janneke a mother. The changes to ‘Moeder helpen’ (Helping mother), now called ‘Mamma helpen’ (Helping mummy), go beyond the cosmetic to the content. There, after the sentence about mummy still being rather weak and unable to work, it says, ‘But nevermind. Jip and Janneke are home. And they can help. Janneke can do the dusting. And she can wash the windows, if necessary.’ It’s a bit half-hearted. Jip and Janneke can both help now, the sentence about Janneke being so good at keeping house has been removed. But it’s still Janneke who can dust and clean the windows.

It’s really an impossible task. Texts from a different era, expressing a different Zeitgeist, cannot be modernised with a few slight adjustments. But it’s easy to criticise the publisher of Jip and Janneke, either for having the audacity to meddle with it or the opposite, for not having intervened decisively enough. It is and remains an exercise in a delicate balance. On the one hand, we don’t want to enforce prejudices and stereotypes that are already floating around the heads of young children who have insufficient baggage to withstand them. On the other hand, the work of Schmidt has so many good qualities that we hope that new generations will continue to enjoy them, and respect for the text demands that we’re very conservative when adapting it.

Old and new cover of De verloren zoon (The Lost Son)

Old and new cover of De verloren zoon (The Lost Son)More than forty years after I first read it, I went to the book shop, curious as to whether De verloren zoon was still available and whether the publisher had made changes to it. The comic book was positioned front and centre of the Jommeke series row. ‘Nikkertjes’ (little niggers) apparently hadn’t made the cut, but ‘zwartjes’ (little blacks) remained. The image of the white man bringing civilisation remains standing. De verloren zoon is, after all, a comic strip dating back to 1965. At the time Nys wasn’t particularly unusual in not having shaken off colonial thinking. Nevertheless, we can reasonably wonder whether he gave any indication of personal insight in 2003, when he said in an interview that he had laid down in his will that Jommeke must never come into contact with violence, sexism or racism.

I just hope that future owners of this comic strip are wiser than I was back then. But really, I think the publisher and bookshop, in this case, should have had the wisdom not to keep on reprinting the material and instead to bin them. It’s not like it would mean the loss of a masterpiece. It’s a rather banal and outdated text. While it’s still the case that racism remains alive and kicking in the school playground and on the football pitch, while statistics still show that discrimination is rampant on the labour and housing market, we can’t afford to sow racist ideas in children’s minds and to trust that they’re clever enough to recognise them as offensive.

Website House of the Book