Charles Degeyter Blurs the Boundaries of the Natural World

Charles Degeyter (b. 1994) is fascinated by what happens when natural and artificial objects meet, merge or exchange places. His assembled and sculpted artworks raise questions about surface and reality, about collecting and cultural appropriation, and about our relationship with the environment.

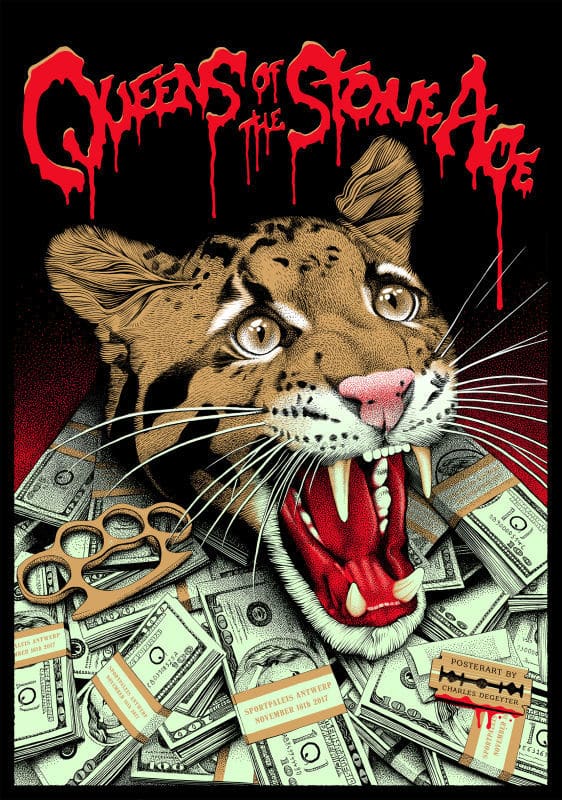

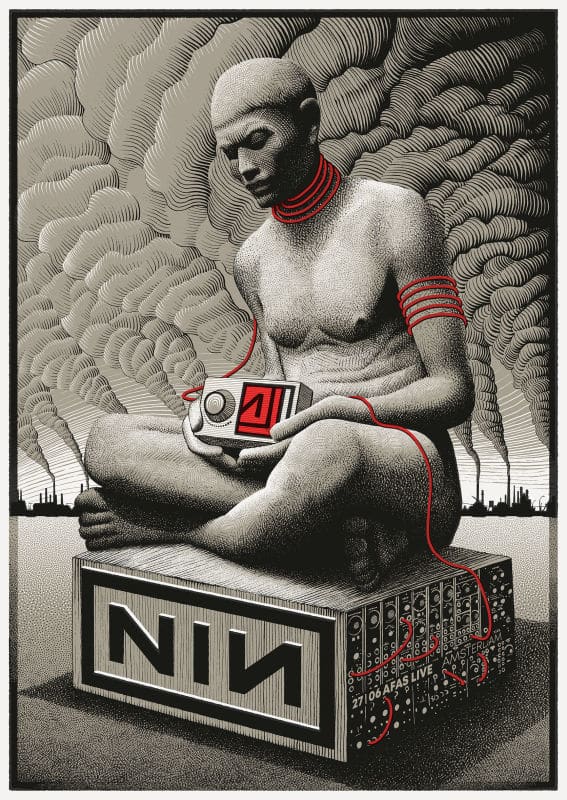

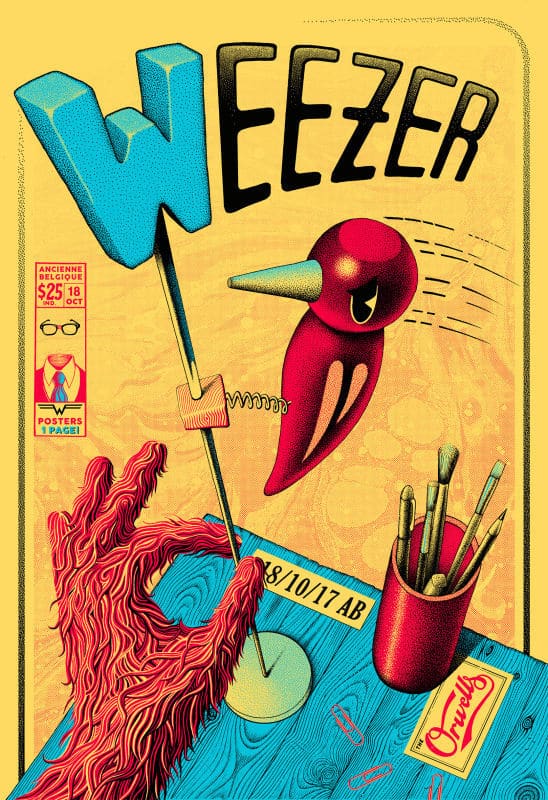

Born in Bruges, Degeyter studied industrial design at Ghent University, at the same time developing a fruitful sideline as a poster artist. He began in his teens, drawing flyers for The Pit’s, a rough and ready music club in Kortrijk, before moving on to make screen-printed posters for touring rock groups and for festivals. After graduating in 2016, he continued this graphic work, building a portfolio that now includes posters for big-name bands such as Weezer, Queens of the Stone Age, and Nine Inch Nails.

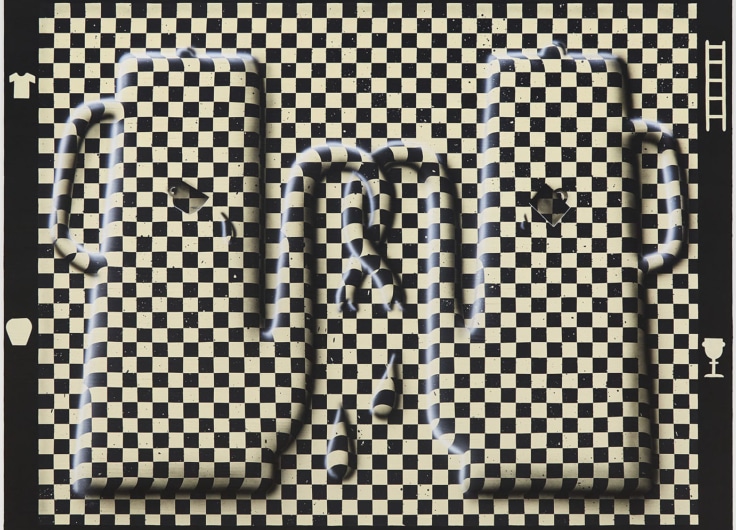

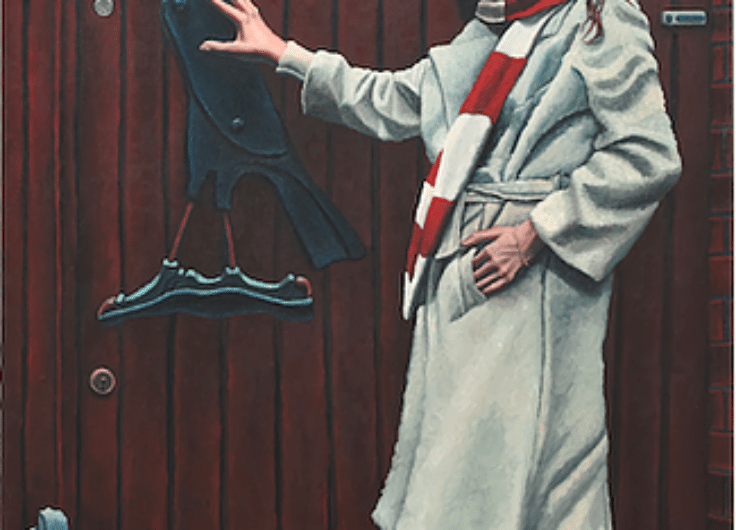

Charles Degeyter designed posters for Queens of the Stone Age, Nine Inch Nails, and Weezer

Charles Degeyter designed posters for Queens of the Stone Age, Nine Inch Nails, and Weezer© Charles Degeyter

Degeyter’s poster art is inspired by natural ephemera, such as corals, shells, insects, skulls and stuffed animals, along with their more respectable cousins kept in museums and illustrated in antiquarian books. He also draws on a wide range of cultural references, such as cartoons, movies, and of course rock music and its tradition of poster art.

Degeyter's poster art is inspired by natural ephemera, but also draws on a wide range of cultural references

In 2018 Degeyter started to talk about producing more personal work, which from sneak previews appeared to be a continuation of his drawing and printing. Yet when this work was shown in 2019 it turned out to be three-dimensional, a diverse range of objects inspired by (and sometimes made from) children’s toys.

A particularly strong motif in this work is the hermit crab. Under normal conditions, these small crabs make their homes in empty seashells, but more recently they have been found living inside bottle tops and other bits of marine trash, including toys. Degeyter took this idea and ran with it, building a series of works that combined preserved crabs with plastic toy heads. Some of these heads came from real toys, while others were made to measure.

Vivian #1 & Vivian #2, 2019, mixed media, courtesy of the artist & Tatjana Pieters

Vivian #1 & Vivian #2, 2019, mixed media, courtesy of the artist & Tatjana Pieters© Charles Degeyter

One striking series takes inspiration from the outsider artist Henry Darger, who spent decades privately writing and illustrating a fantasy tale about seven girls engaged in an epic struggle against child slavery. Darger’s images of these Vivian girls were traced from children’s colouring books, and Degeyter set out to imagine how these prototypes would have looked as toys. And, as toys, how they would look washed up on beaches, inhabited by hermit crabs.

The combination of crabs and doll heads already makes for a powerful image, an uncanny union of the natural and the unnatural that is easy to interpret as a commentary on plastic pollution in the oceans. This is the gift we are giving to our children. But the Vivian series, once you see the connection, starts to take on other connotations, where the ocean is a metaphor for Darger’s troubled subconscious, a breeding ground for strange hybrid creatures.

Alongside these assemblages, Degeyter made pictures of these doll crabs using Perler beads. These are small, brightly coloured plastic beads that can be arranged on a pegboard to create a picture, which is then fixed by fusing the plastic using a household iron. The result is an oddly physical form of pixelation, but Degeyter took his inspiration from Ancient Greek mosaics, incorporating antique borders and breaks suggestive of damage during excavation. He used the same Perler technique to make gory mosaics of conflict between toy cats and real cats.

ΑΘΕ, recto and verso, 2019, mixed media, courtesy of the artist & Tatjana Pieters

ΑΘΕ, recto and verso, 2019, mixed media, courtesy of the artist & Tatjana Pieters© Charles Degeyter

Ancient Greece was also the inspiration for ΑΘΕ, a bright plastic figure of an owl perched on a rock, under a glass dome of the kind used to display stuffed animals. Look behind this plastic shell, and it does indeed conceal a small stuffed owl. The plastic image is inspired by the owl of Athena, depicted on ancient Greek coins along with the ΑΘΕ abbreviation. Degeyter says his idea was to question how much we have evolved (or devolved) since those ancient times, but the effect is rather to drive home a contrast between surface and reality, between the bland, empty eyes of the plastic owl and the fierce look of the ‘real’ owl.

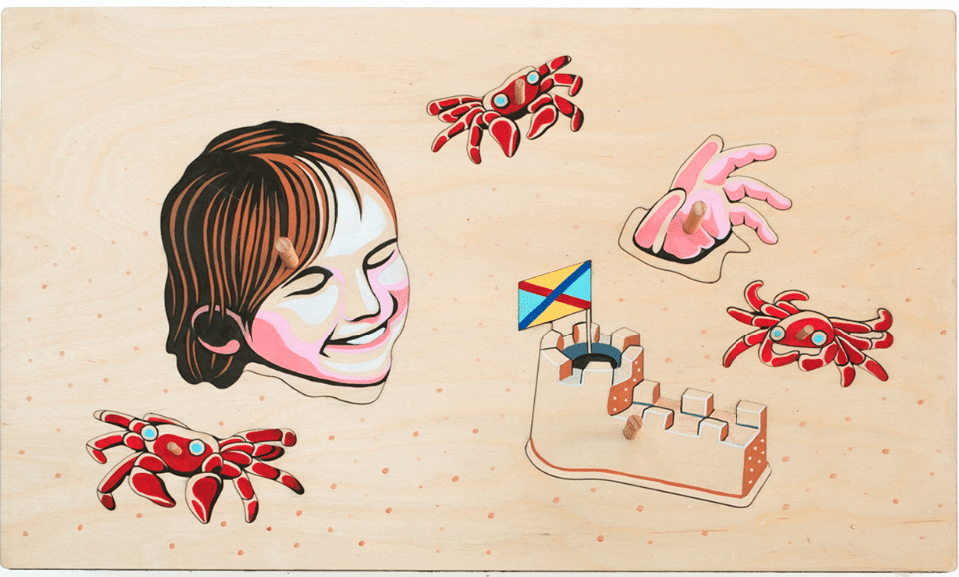

This explosion of work, spread across one solo exhibition and two group shows during 2019, also included a number of pieces that engage more explicitly with toys. In Vivian in the Sand, it is the kind of toy where cut-out shapes are fitted into a wooden board. In this case, however, the shapes are removed to reveal a shallow sandbox containing ‘real’ counterparts of the images painted on the cut-outs: a preserved crab under the picture of a crab, and under the picture of a laughing girl, one of Degeyter’s Vivian girl heads, its tongue poking out as if strangled. The result is an anti-toy, something sinister rather than playful.

Vivian in the Sand, 2019, mixed media, courtesy of the artist & Tatjana Pieters

Vivian in the Sand, 2019, mixed media, courtesy of the artist & Tatjana Pieters© Charles Degeyter

Then there is Turtle Sandbox, a large plastic turtle whose shell flips up to reveal a sandpit for children to play in. Inside, Degeyter has made a nest of ping-pong balls, from which realistic models of baby turtles have hatched. The toxic relationship between plastic and the marine world is inverted and reflected back on itself.

In 2020 Degeyter revealed a series of pet sarcophagi, plastic containers for dead finches, parrots, hamsters, and guinea pigs. Each presents a bright, idealised image of the animal, while inside is the original pet, preserved. He describes this as a playful approach to transience: after the death of a pet, isn’t it logical that it should be transformed into a toy that a child can continue to cherish?

Amanda & Monty, 2020, mixed media, courtesy of the artist & Tatjana Pieters

Amanda & Monty, 2020, mixed media, courtesy of the artist & Tatjana Pieters© Charles Degeyter

Beyond this stated aim, the pet sarcophagi have all sorts of other resonances. Again, there is a tension in the work between the natural and the manufactured, between the real and the ideal. There is an echo of the ancient world, not Greece this time but Egypt, where cats and other sacred animals were also mummified and placed in sarcophagi. And there is a pleasing sense that Degeyter is undercutting the bombast of Damien Hirst’s work with preserved animals. Instead of a four-metre-long tiger shark in a tank of formaldehyde representing The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, here is a 30cm hamster in a casket, representing the very real possibility of death as first encountered by a child.

Degeyter may have had his tongue partly in his cheek when he began this series, but he has since been asked by friends (and strangers who have seen his work online) to provide caskets for their own deceased pets. The concept turns out to have a genuine appeal.

Angaku, 2021, human skull, gold leaf, PLA plastic, polymer clay, custom stand, pearls, courtesy of the artist & Tatjana Pieters

Angaku, 2021, human skull, gold leaf, PLA plastic, polymer clay, custom stand, pearls, courtesy of the artist & Tatjana Pieters© Charles Degeyter, photo by Artuur Vandekerckhove

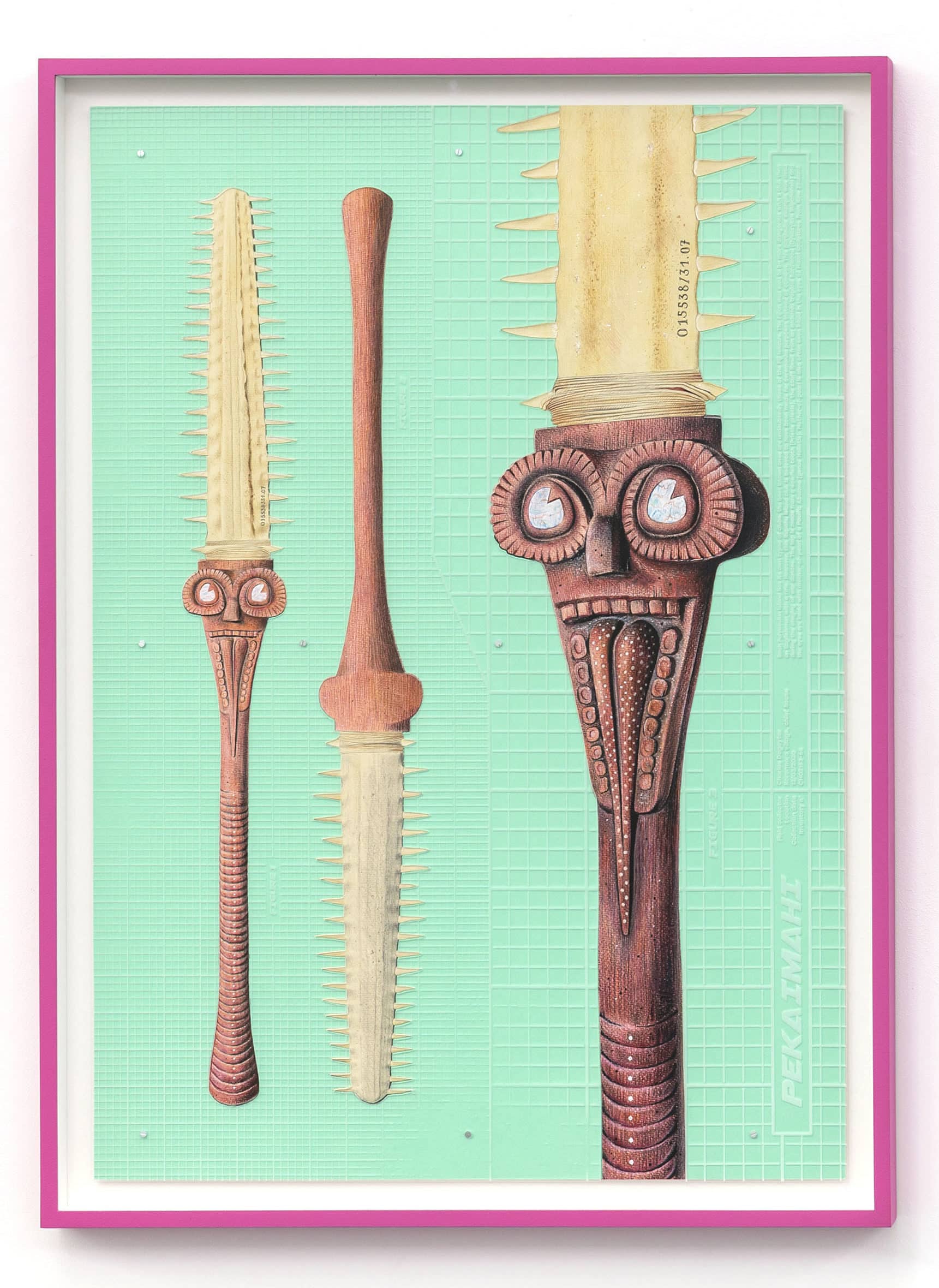

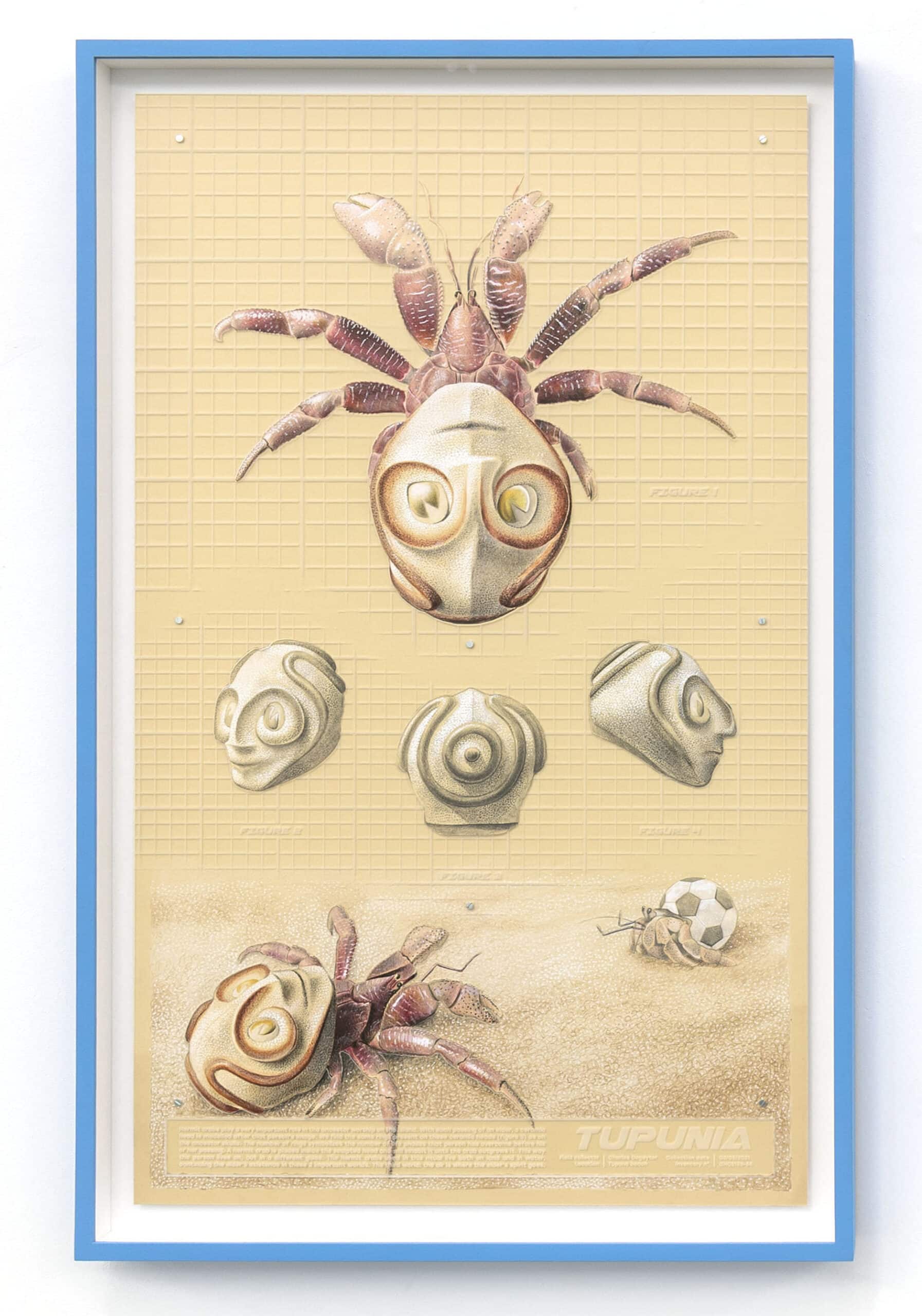

In the summer of 2020, Degeyter had a residency at the Verbeke Foundation in Kemzeke, East Flanders, where he began another new line of thought. He produced artefacts from the Moani people, indigenous to the entirely fictional Rupahu Island in the Pacific Ocean. These include life-sized skulls and shells, covered in intricate designs suggestive of facial tattoos, and of the scrimshaw art produced by sailors on 18th and 19th-century whaling boats. In Degeyter’s thinking, these whalers had stopped at the island, and their methods were taken up by the islanders.

There is also a gilded skull concealing a maze (another hidden toy), a saw-fish bill mounted on a carved handle, a decorated marker buoy, and a tribal mask inhabited by a hermit crab. Degeyter’s current exhibition, at the Tatjana Pieters Gallery in Ghent, builds on this work with a series of detailed, ethnographic drawings of the Rupahu Island artefacts. These deepen the sense in which the project is an inquiry into western perceptions of otherness and what it means to collect other people’s cultures.

Pekaimahi plate and Tupunia plate, 2021, pencil on paper, engraved acrylic in glass and wooden frame, courtesy of the artist & Tatjana Pieters

Pekaimahi plate and Tupunia plate, 2021, pencil on paper, engraved acrylic in glass and wooden frame, courtesy of the artist & Tatjana Pieters© Charles Degeyter, photo by Artuur Vandekerckhove

In a way, all these artefacts feel authentic, the dense engraved lines that decorate them somehow familiar, their status dignified by being displayed in elegant museum cabinets or drawn with forensic accuracy. But the eyes that peer out of the skulls are cartoon eyes. Does that make them fakes, or is this simply the influence on the local tradition of doll heads being washed up on their shores? Perhaps this is not an ethnographic collection from the past, but a post-apocalyptic cargo cult already in the making.

Rupahu Island Drawings

Tatjana Pieters Gallery, Ghent, until 18 April

Rupahu Island Artefacts

Verbeke Foundation, Kemzeke, until 18 April

website Charles Degeyter