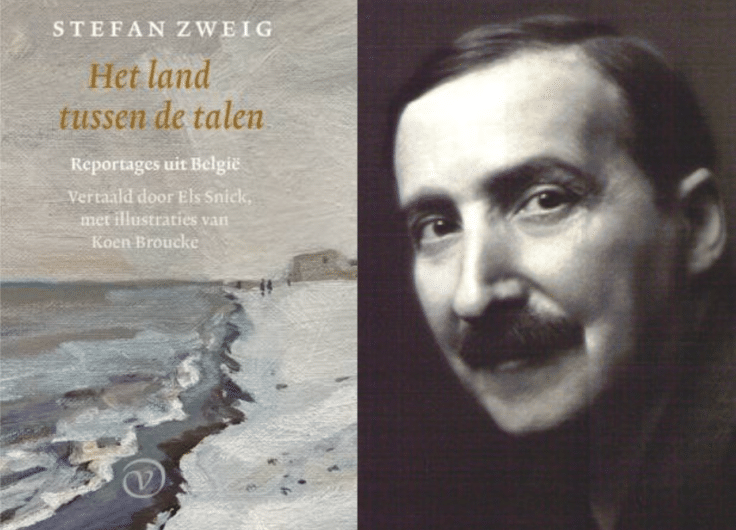

A Shadowy Series of Unrealized Books: The Fate of Dutch-American Author Dola de Jong

‘Splintered, played out between two languages and two continents, marked by genocide and war’. This is how Mirjam van Hengel summarizes Dola de Jong’s writerly essence. Van Hengel wrote a biography of the Jewish writer and dancer who migrated to New York to escape the Nazis. There, she wrote successful children’s books and young adult literature, and some internationally acclaimed novels. But the book that she always intended to write – about how to carry on after the Second World War – never materialized.

In 1943, in the middle of the war, a children’s book about a Dutch family on the eve of the German invasion was published in the United States: The Level Land. The father is a family doctor, the mother the one holding the family together, and there are five children, the oldest daughter seriously concerned about the rise of Hitler.

The Level land (1943)

The Level land (1943)Don’t let yourself get carried away, says the father to this daughter. Surely it will all be okay.

It was exactly what the author of the book, Dutch writer, journalist, and dancer Dola de Jong (1911-2003) had experienced herself. Even before the German occupation, she sensed that things might end badly for her and her Jewish family. She saw the growing flow of Jewish refugees from Germany. She heard the anti-Semitic remarks all over the street. She decided: I have to get out of here. When she tried to convince her family to leave, they laughed at her.

She was exaggerating, said her father. Surely it would all be okay.

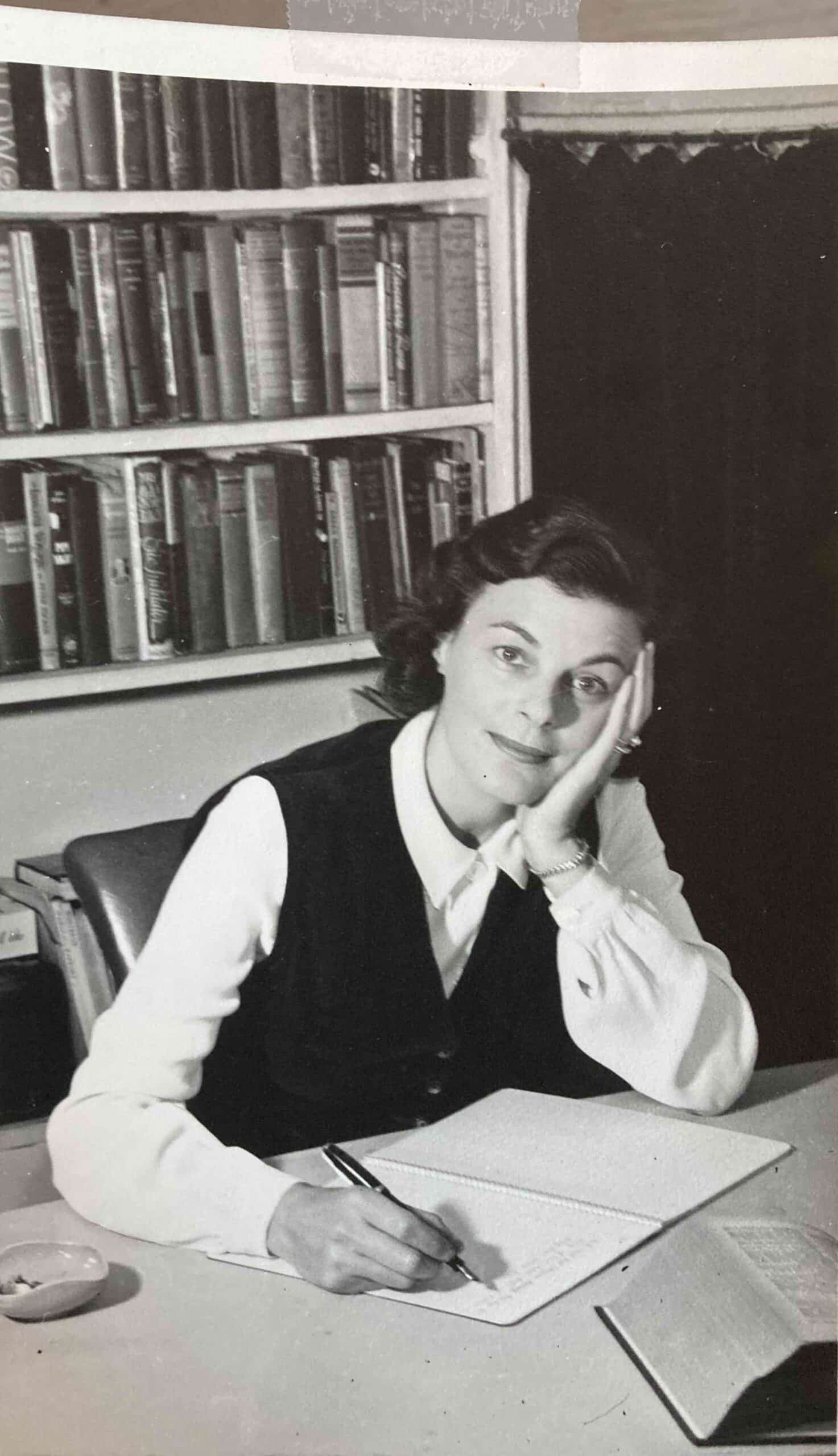

Dola de Jong in Amsterdam, circa 1935

Dola de Jong in Amsterdam, circa 1935© private archive De Jong/Joseph

So I’m on my own, she thought.

Her train departed from Amsterdam Central Station very early in the morning. She had slept too deeply and was awoken by the alarm clock in a daze. It was still dark, her room a strange empty kingdom that everyone had already left behind.

She walked on bare feet to the window. Just as she opened the curtains the streetlamp across the road went out, and the white morning light took over. She took off her nightgown, went to the closet, and looked at herself in the mirror: a tight face above a tight, sinewy body. A serviceable vehicle. She took a sip of water, brushed her hair. The nightgown, still warm, with the other clothes in the suitcase, locked shut. Get up, get dressed. Sudden shock at the sight of her freshly slept-in bed: how do you leave something like that behind? Who would be the first to see this place next, what would the house reveal about her?

She looked at the rest of her books, at the linen closet, the typewriter, the pile of papers and clippings on the shelf next to the desk. Ran her hand across the back of the chair, the rounded frame. There was a snagged thread in the upholstery. She hooked her finger through it, momentarily wavering. She braced herself. Coat on.

She went down the stairs with her luggage, opened and closed the door, threw the key through the mailbox, and turned around.

To the end of the road, a left turn, and towards the tram stop at Roelof Hartplein. The day had already begun at Het Nieuwe Huis, at the crossing of the tram tracks. Stoves were stoked, smoke shot up into the pale sky. Rattling carts on their way to the Albert Cuyp, the ringing of the tram in the distance. She carried one suitcase, no more, and she was determined.

[Excerpt from Dola. Over haar schrijverschap en de hele mikmak. De Bezige Bij, 2023]

Her flight on April 10th, 1940 saved Dola de Jong’s life. Because, of course, it was not all going to be okay as her father had hoped. A few years later, more than a hundred thousand Dutch Jews, including the entire De Jong family, would be murdered. She would never see her father again, though she didn’t know this yet when she wrote her novel The Level Land. She had only just moved to New York, and had no idea how her family was doing. ‘Had they fled? Had they hidden? Were they alive? I thought about them all the time, and about Holland, my homeland. And so as writers do, I started to write about Holland and a Dutch family, to reassure myself, and to bring closer to myself that which I had left behind.’

Return to the Level Land (1947)

Return to the Level Land (1947)The book became an instant success in the United States and later in Japan. De Jong received sacks full of fan mail. But the book was never published in the Netherlands. Not then, and not later when she wrote a sequel, Return to the Level Land. This is Dola de Jong’s oeuvre in a nutshell: splintered, played out between two languages and two continents, marked by genocide and war.

‘Hitler and his comrades put me on a raft and pushed me away from shore’, she would later write. ‘I belong to the small handful of Jews who saved their own lives, whether by luck, by chance, or by the kind of entrepreneurial spirit that does not shy away from flight, the unknown, the leap into darkness.’ What happened in her life after that leap? And before then: who was Dola de Jong?

Dola in New York

Dola in New York© private archive De Jong/Joseph

Daughter of the wealthy, secular Arnhem merchant Salomon de Jong and the German Lotte Rosalie Benjamin. A bright child, often lively, sometimes timid and withdrawn. Her mother died when she was five years old – a loss from which De Jong never quite recovered. Before the trauma that the war would cause, came the trauma of a lonely, neglected childhood. As a teenager, she wanted to become a dancer, but her father forbade it. As a compromise, she was allowed to go into journalism and so learned to support herself through writing, which she did for the entirety of her life. Her children’s books and young adult fiction were published as early as the 1920s, and her articles were regularly printed in countless newspapers and magazines. Fresh in tone, sparkling.

Still, she ultimately left Arnhem for Amsterdam to make her dance dreams come true. Within a few years, she found herself in the middle of the avant-garde dance scene: she was part of the Yvonne Georgi ballet and followed a summer course with renowned German choreographer Kurt Jooss. She wrote her first novel for adults about the world of dance, Dans om het hart. A novel through and through: hard-working dancers, competition, complete lack of prestige, sensuality and sensoriality – sweating bodies, smoking stoves, sex, unwanted pregnancy, loneliness, and systematically thwarted female ambition.

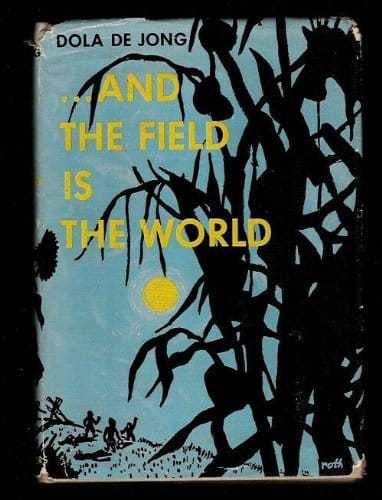

And the Field is the World (1945)

And the Field is the World (1945)De Jong’s writing was based on what was close to her own life. Her best novel, And the Field is the World, is about refugee children in the Moroccan city of Tangier, where she herself spent the first year of the war. She portrays children as the great victims of the war, a perspective that continues to resonate to this day. But with this, she also forced the war into a corner: not too close to her own adult life in which her own adult parents and brother were the victims. This formed a part of the repression she continued to rely upon throughout her life.

She believed there were only two options for people like her, those who survived the Holocaust while their entire family was massacred: repress, or do away with oneself. ‘In our ability to forget lies our strength to live on.’

Before the trauma that the war would cause, came the trauma of a lonely, neglected childhood

And Dola de Jong lived on. She danced in a circus in the boomtowns along the American West Coast. She immersed herself in the cultural life of New York City. Found her way to other Dutch people in the city, to journalists and writers, to people who could help to advance her career. She worked for international radio. And she found a publisher who published her children’s books and introduced her to Maxwell Perkins, the famous editor of Hemingway and Fitzgerald, who recognized her talent. For him, she wrote The Field is the World (1945, translated into Dutch in 1947) and started another book.

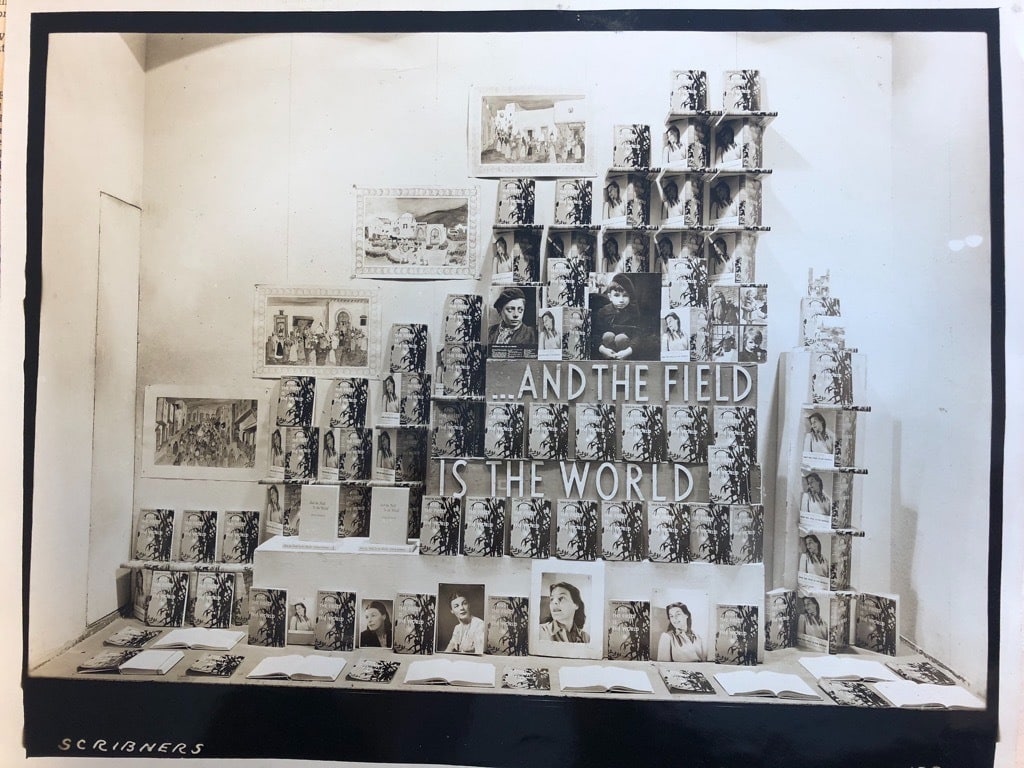

The famous New York bookstore Scribners promotes Dola de Jong's novel 'And the Field is the World'.

The famous New York bookstore Scribners promotes Dola de Jong's novel 'And the Field is the World'.© private archive De Jong/Joseph

But then things went wrong.

She wanted to write another novel about that which was so deeply personal to her: about life as a refugee in a new world. She sent a draft to Perkins, but knew it was no good. She sent a fragment to the writer Greshoff, but noted to him too: it’s not working.

‘As you can see, I wrote it in the first person. But the further into the narrative I go, the more it pains me. It was originally my intention to write in the first person, but the first-person-narrator narrates alone and remains out of context; more or less as an outsider who observes the refugee objectively, relating how she is (or isn’t) included by her American colleagues. But right from the start, the narration developed against my intent. This, of course, reveals how little distance I have from the story, how much I identify directly with the main character.’

Dola wanted to write a novel about that which was so deeply personal to her: about life as a refugee in a new world.

Dola wanted to write a novel about that which was so deeply personal to her: about life as a refugee in a new world.© private archive De Jong/Joseph

At least five times, De Jong started on that great novel in which the war, the refugee or the immigrant stood central – always with a new title, from a slightly different angle, with renewed determination. Sometimes she signed contracts for them, but the books never came close to completion.

After the war she wrote just one more book for adults – De thuiswacht/The Tree and the Vine – but the book she really wanted to write, about her own fate and the war, didn’t pan out. All that remains is a shadowy series of unrealized books, always with new variations on the title. The House of the Guileless, The Sum of all Moments, Return to Arnhem, The Two Mathildes, The Search for Maria Bellissima.

De thuiswacht (1954), translated as The Tree and the Vine (1961)

De thuiswacht (1954), translated as The Tree and the Vine (1961)These titles also show that she stopped writing in Dutch. In interviews she said that she lived between two languages and two worlds, but at a certain point she only wrote in English anymore. She worked for book clubs and publishers as a scout – she translated Jan Cremer and Jef Geraerts, among others – and she was one of the first to translate Anne Frank’s diary into English (a publishing project that was tangled up in misunderstandings and ultimately fell through). She divorced and found a new husband, was left and found another husband, got older and went to college, got older and got her driver’s license – her energy and perseverance never seemed to run out.

But underneath it all, her wounds festered. Sometimes she would fly into a rage at nothing, lashing out fiercely at the people around her, even the mildest of friends – she was lifelong friends with Leo and Tineke Vroman, who also lived in New York, and managed to argue even with them. The root cause, always, was the pain of the survivor: guilt and fierce powerlessness in the face of the great injustice.

She was one of the first to translate Anne Frank's diary into English

Responding to a critic who she felt understood her well, de Jong wrote to her editor: ‘He said that the ghost of my life was the concentration camp. This is somewhat true. Not the camp itself, but the implication of the camp, the killing of people like vermin. I always have this feeling that I should be under the ground in Poland. I escaped purely by chance and luck. In other words, what happened has somehow alienated me from people, isolated me, in a way (…). Of course you live on, you are outwardly optimistic, normal, ordinary, but if you touch the old wound, you immediately get stuck.’

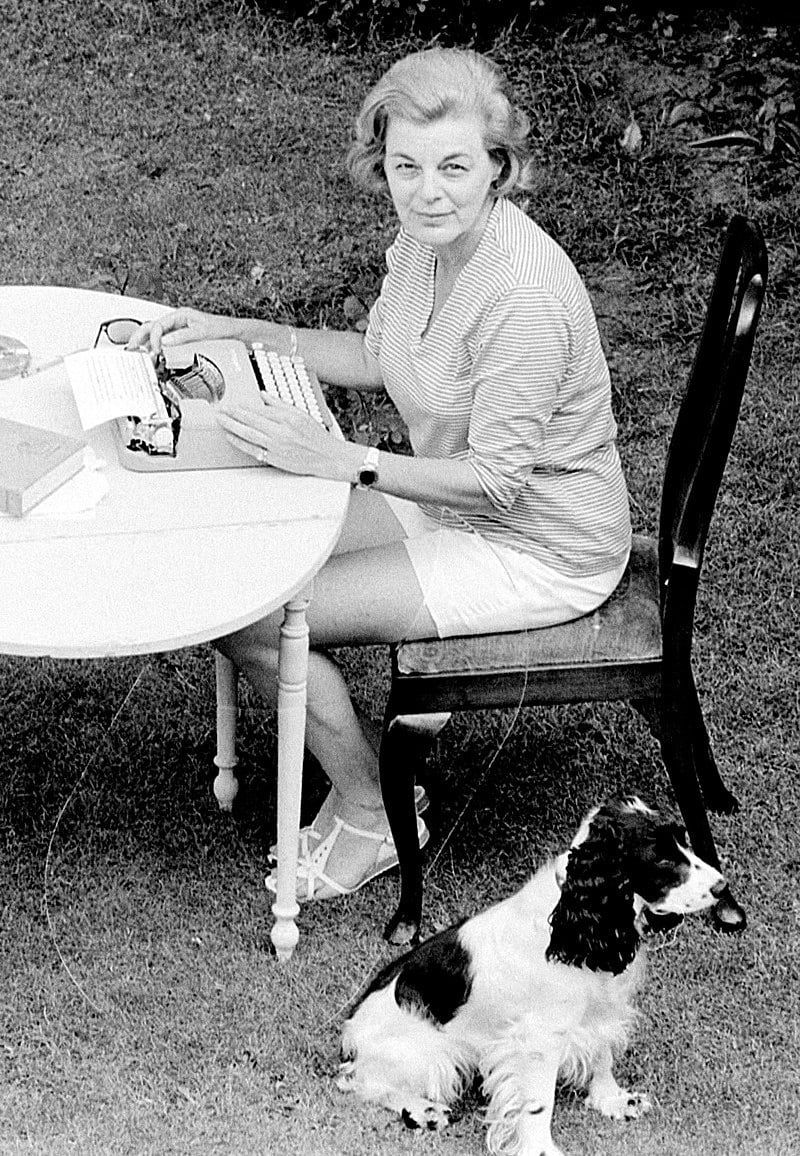

Dola de Jong at work during a holiday in the Netherlands, 1963

Dola de Jong at work during a holiday in the Netherlands, 1963© © Noord-Hollands Archive, collection Photo Press Agency De Boer / WikipediaWikipedia

It’s the winners who make history, and the writers who faithfully build their own oeuvres who we continue to read. But the story of Dola de Jong, a writer whose writing career stalled, is perhaps a more important story than that of a winner.

Her story is about her books (though the only one that endures is her fantastic novel about Tangiers, created out of context in a house by the sea, ignorant to exactly what was happening in the war on the other side!) but more than anything it is about living on. Writing or not writing, furious or restrained, energetic or exhausted – as one’s life can be.