Eileen Stevens’ Choice: Gerard Reve and Machteld Siegmann

Every month, a translator of Dutch into English gives literary tips by answering two questions: which translated book by a Flemish or Dutch author should everyone read? And, which book absolutely deserves an English translation? To get publishers excited, an excerpt has already been translated. This time you will read the choice of Eileen Stevens. In addition to Anna Enquist’s The Homecoming, her many Dutch-to-English translation credits include a co-translation of Connie Palmen’s Your Story, My Story (nominated for the 2022 Dublin Literary Award) and Fred Brouwer’s Beethoven in the Bunker. She has also translated numerous essays on classical music and the arts.

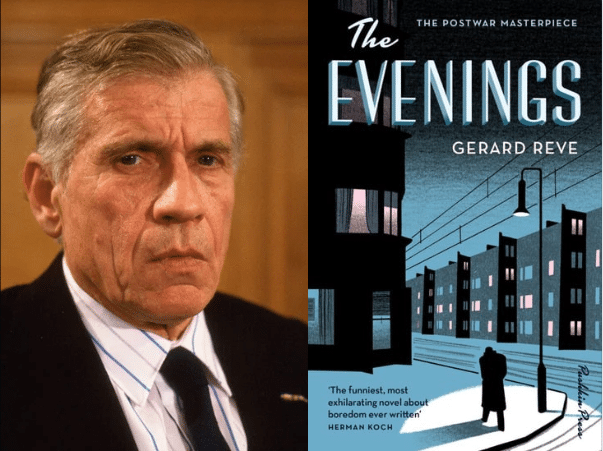

Must-Read: ‘The Evenings’ by Gerard Reve

Gerard Reve’s 1947 debut, De avonden (The Evenings)

takes me back to my lost years as a bored teenager in suburban New Jersey. The book remains popular with many Dutch readers and is ranked among the Netherlands’ best novels of all time. Reve is seen as one of the greatest post-war Dutch authors. He was also the first openly gay writer in the country’s history. Reviews have compared the book to J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and Camus’s The Stranger. Oddly, The Evenings was not translated into English until 2017, when Sam Garrett turned his talented eye to it. By all accounts, humour presents one of the greatest challenges to translators, and (luckily) AI is still not up to the job. Which is why I have such enormous respect for the way Sam captured Reve’s dry, subtle wit. The main character, Frits, is bored in that thought-wilting way unique to his stage of life. He’s so irritating you don’t know whether to laugh or smack him.

Amsterdam forms the backdrop of Reve’s investigation into youthful ennui. It’s the last week of December, eighteen months after the end of World War II. Described by Tim Parks as ‘a cornerstone manqué of modern European literature. […] Reve’s sparkling collage of acute observation, droll internal monologue and pitch-perfect dialogue keeps the reader breathless right through to the grand finale.’

The book’s protagonist, Frits van Egters, works a mind-numbing clerical job. He still lives at home, and, in the novel, there’s not much action. We follow Frits’ growing irritation at his parents and brother. He escapes his claustrophobic surroundings by making the rounds of the neighbourhood, drinking, smoking, dropping in on friends, and attempting to deal with the punishing slowness of the hours and days in post-war life. I was especially impressed by the book’s mood – the greyness of the winter light, the smell of over-cooked Brussels sprouts, and the hiss of the coal stove. Reve presents a compelling photograph of the post-war era. I’m told that post-war critics were shocked by Reve’s book, and they had concerns about the author’s welfare. ‘I live,’ he whispered, ‘I breathe. And I move. I breathe, I move, therefore I live. What could possibly happen? Calamities, pains and horrors may come. But I live’.

Gerard Reve, The Evenings, translated by Sam Garrett, Pushkin Press, 2017, 320 pages

Read our review of The Evenings HERE.

Read our profile on Gerard Reve HERE.

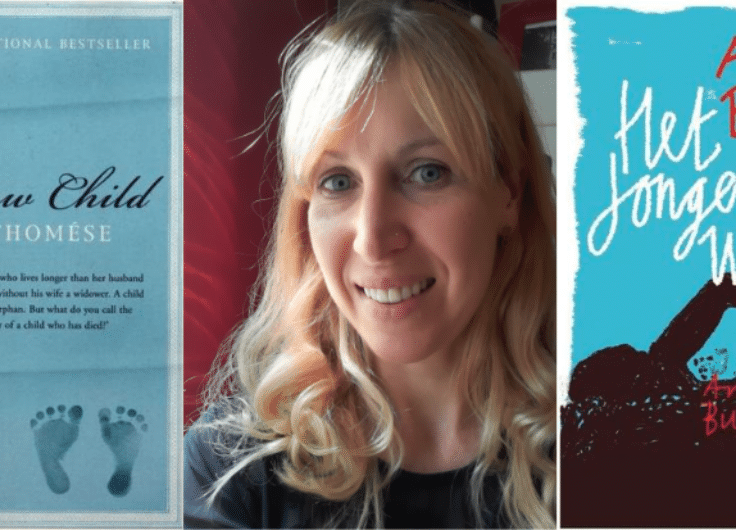

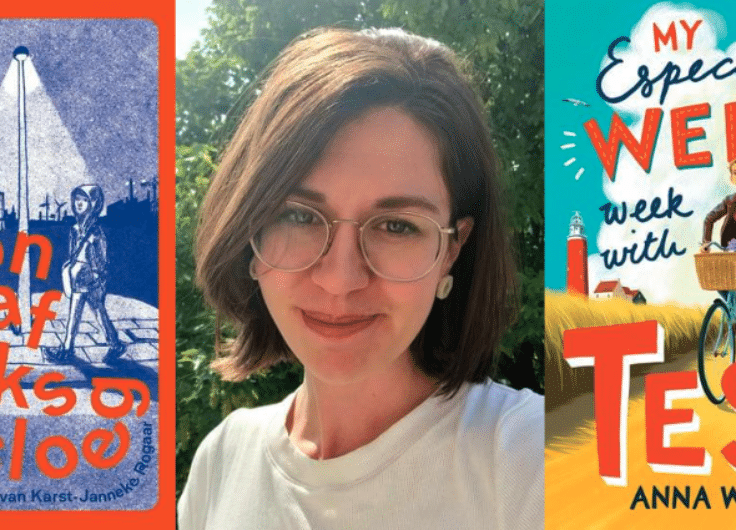

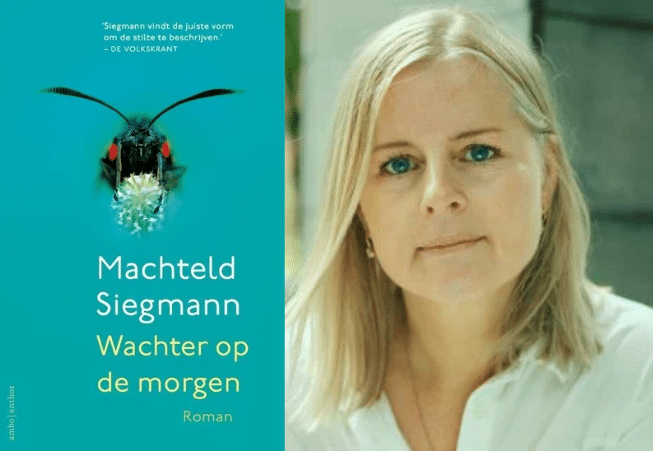

To be translated: ‘Watchman for the Morning’ by Machteld Siegmann

© Bianca Sistermans

When I translated the sample of Machteld Siegmann’s Watchman for the Morning, the main character captured my heart. Tak, the 72-year-old first-person narrator, moves in temporarily with his granddaughter, Aria, after a lorry crashes into his house. Aria is a young, unmarried artist who, unlike Tak, lives in the city; she’s eight months pregnant. When Aria goes into early labour prior to giving birth at home, Tak – Dutch for twig or branch – decamps to the downstairs neighbour’s apartment. During that long, sleepless night, he tells his life story to a stranger. What follows is a simple and compelling tale, starting with Tak’s childhood during the Great Depression, then going on to his mother’s death, the Second World War, his surprising love affairs and his broken relationship with his now estranged daughter, Marina. Reading Watchman for the Morning filled me with hope – it’s a unique tale of Tak’s reconciliation with life and fate, with himself and those dear to him.

The book’s young and promising author, Machteld Siegmann (b. 1972) studied Dutch Language and Literature and Cultural History and is a writer and editor. Her 2019 debut, De kaalvreter (The Days of the Locust), put Siegmann on the map as a new talent on the Dutch literary scene and earned her several awards, including the Bronze Owl, an annual Flemish literary prize for the best debut. Watchman for the Morning is her second novel, and Aloha, a collection of short stories, will be published in early 2024.

Machteld Siegmann, Wachter op de morgen, Ambo|Anthos, 2022, 248 pages

Excerpt from ‘Wachter op de morgen’, translated by Eileen Stevens

Do you mind me staying here a while? Because to be honest, I don’t know how long this could take. The baby might arrive this evening, or during the night, or it could be tomorrow. Let’s hope he doesn’t make life too difficult for his mother. Or she, because it could just as easily be a little girl.

If it goes on too long, may I sleep on your couch? Thanks, that’s mighty neighbourly. I don’t want to be a burden; just pretend I’m not here. Decorating a Christmas tree is a big job, and with the holidays right around the corner, you haven’t got much time. Wait, let me help you put the tree in the stand.

She knew this afternoon that the baby was on its way. Aria. She was working at her drafting table, and when I brought her a cup of tea, she looked up and said: ‘Grandpa, I think the baby’s coming.’ I thought she was joshing, because she’s not due for another three weeks, and I can’t move back into my house until next week. So, I asked: ‘Why do you think that?’ and she said: ‘I just feel it.’ She glanced from the unfinished sketch to the box of baby things she hadn’t managed to put away, thinking she still had plenty of time. ‘The baby wants out,’ she said, and she seemed so sure of herself, I didn’t dare argue with her. Her first labour pains arrived while we were eating. I asked: ‘Has it started?’ She nodded and held onto the table for dear life. ‘Shouldn’t you call someone?’ I asked, a little panicked, because where was I supposed to go while the baby was being born? She looked me in the eye, and I didn’t have to say a thing: she knew exactly what I was thinking and she had it all worked out. She said: ‘I asked the downstairs neighbour if you could stay with him.’ She’d arranged it without my noticing. ‘And what about you?’ I asked because, of course, I couldn’t abandon her. ‘A friend of mine is on her way over,’ she said. I thought: if only my wife were still alive to be with her. Aria doesn’t want to have anything to do with the baby’s father, see, and her own mother is worse than useless.

Your name is Filip, isn’t it? We sometimes run into each other on the stairs. And I’ve met your little boy, Tim, if I’m not mistaken? You say he’s at his mother’s now? Figured as much. He recently made a drawing for Aria; she taped it to the fridge. She happened to be out when he brought the picture, and when he saw me, he said: ‘Maybe you’d like a drawing, too?’ He must have thought I looked like someone who could use a nicely coloured drawing, and he was right about that. So, he drew a bridge over a river for me. A car was driving over the bridge, and I was at the steering wheel. I said I thought it was splendid and told him about my dog, about how she loves to go for rides. He asked: ‘And where does she sit?’ ‘Preferably in the front,’ I said, ‘so she can keep an eye on everything.’ And at that, he grabbed his coloured pencils and drew the dog. We spent a long time sitting there on the stairs, chatting.

Aria talks about you all the time. Don’t worry, it’s all good. About how you help her when things break down, when there’s a glitch with the electricity or something, and how you have a knack for fixing blocked toilets. She only mentions you in a good way. Like how she can rely on you. It’s nice to know someone is keeping an eye out. That she’s not entirely alone, I mean. Even though she has friends, of course, and she belongs to that artists’ group. They make all sorts of different things, photographs and images. One of them even got her pregnant. So, apparently, it’s not just art they’re making.