From Dwile to Forlorn Hope. This Is Why English Sometimes Sounds Like Dutch

You may have thought that the first Dutch grammar was written in the Low Countries, but a grammar written in London in 1568 has a strong claim to this title. This is just one way in which Britain’s geographical closeness to the Low Countries means that it has played an important role in the history of the Dutch language.

People from the Low Countries have been going to Britain for well over a thousand years. Hebban olla uogala nestas hagunnan… (‘Have all the birds begun nests…’) is arguably the most famous fragment of Old Dutch. It was probably written by a monk trying out his pen in an abbey in Rochester, Kent in around 1100. Before this, in 1066, the Normans under William the Conqueror had successfully invaded England. There were many Flemish soldiers in his army. Some of these stayed in Britain and eventually moved to Pembrokeshire in West Wales. Their descendants spoke a form of Dutch, which may have survived as late as the sixteenth century.

Around 1% of the population of England spoke Dutch as a first language in the late sixteenth century

During the Middle Ages, Dutch speakers traded extensively with ports in England and skilled craftsmen went to England to build and decorate the churches built on money from wool. It is likely that Dutch loanwords entered English at this time, but the closeness of the languages and the fact that most records are in Latin means that it is not easy to establish the precise source of such words. In the sixteenth century, the Protestant Reformation and the Eighty Years’ War led many Calvinists to move to England, where they could practise their faith more freely. They settled in about twenty towns, mainly in eastern England, but also in Edinburgh, Scotland, and spoke different varieties of nederduytsch, literally ‘Low German’, and the word from which English derives its word ‘Dutch’. In fact, around 1% of the population of England spoke Dutch as a first language in the late sixteenth century.

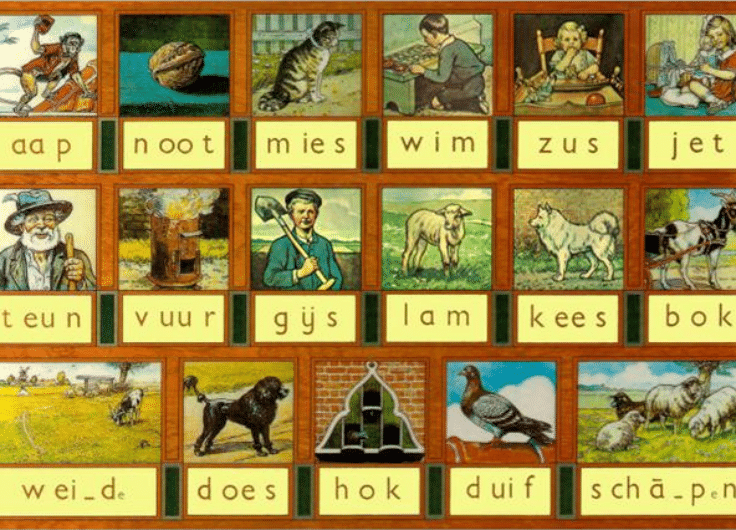

Johannes Radermacher wrote the first Dutch grammar in 1568

Johannes Radermacher wrote the first Dutch grammar in 1568© Wikimedia Commons

In 1550, a Dutch church was established in London. In 1568, one of its members, Johannes Radermacher, wrote what is arguably the first Dutch grammar. It was not completed and not published, but it predates the better-known grammar Twe-spraack vande Nederduitsche letterkust by 16 years. Many early Dutch sonnets were written in England by Calvinist exiles such as Jan van der Noot. He published two collections of verse Het Theatre and Het Bosken (‘The Grove’) in London in around 1570. The English-born playwright, Thomas Dekker, who may have had Dutch forefathers, peppered his plays with lines of Dutch and cod-Dutch.

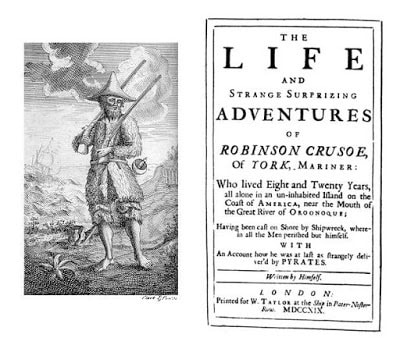

The title page of Robinson Crusoe - the name was taken from Flemish immigrants to Norwich

The title page of Robinson Crusoe - the name was taken from Flemish immigrants to Norwich© Wikimedia Commons

Norwich in the county of Norfolk was the second city of England at this time. In 1578 a third of the city’s population spoke Dutch as a first language. The city does not have public ‘squares’ but ‘plains’ possibly from the Dutch plein. Other local words from Dutch are ‘dwile’ (Dutch dweil) for a cloth and ‘crowd’ meaning ‘to push’ (cf. Dutch kruiwagen = wheelbarrow). One family from Flanders, the Crusos, would have their name immortalized in Daniel Defoe’s famous character, Robinson Crusoe, as one of its members sat next to Defoe at the Dissenters’ Academy in London.

Thousands of Dutch went to England to drain marshlands and some of them settled there. In the Fens in West Norfolk is the town of Nordelph, which probably owes something to Dutch (cf. Delft). Much of the drainage work was led by the Zeelander, Cornelis Vermuyden. His motto, Niet Zonder Arbyt (“Nothing Without Work”), which hangs on a house in Fen Drayton was adopted as the official motto of South Cambridgeshire District Council. Several placenames with ‘Dutch’ in them attest to the presence of Dutch migrants in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The Coat of Arms of South Cambridgeshire District Council with Vermuyden's motto "Nothing Without Work"

The Coat of Arms of South Cambridgeshire District Council with Vermuyden's motto "Nothing Without Work"© Wikimedia Commons

On Canvey Island, where Dutch also drained marshland, there is a Dutch Cottage. In Colchester, Essex, there is the Dutch Quarter. Colchester was the birthplace of Petrus Leupenius, who became an important Dutch grammarian in the seventeenth century. In South Yorkshire there is the Dutch River, a canal engineered by Vermuyden. Services were held in Dutch in the ‘Dutch Chapel’ in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, for about one hundred years. One of its purposes was to keep Dutch herring fishermen out of the pubs and out of trouble when the herring fleet called into the port to land its catch and mend its nets. Other Dutch speaking communities were established in Mortlake in Surrey, where there was a large Flemish tapestry works, and Sandwich in Kent, where at one point there were more Dutch speakers than English speakers.

As a result of Dutch soldiers’ involvement in the English Civil Wars and wars between the English and Dutch, several Dutch loanwords entered English. These include ‘blunderbuss’ and ‘drill’ in the sense of doing military exercises. Also, the English phrase ‘forlorn hope’, i.e., a completely lost cause, comes from the Dutch verloren hoop, i.e. a lost troop or company. Dutch and Flemish contact with Scotland led to Dutch loanwords entering Scottish dialects. One example is ‘leppel’ in the Shetland dialect from the Dutch lepel, ‘spoon’ and another is ‘ratt’ for a file of soldiers (Dutch rot) which was used in Toun Rats, the nickname for the unpopular town guards in Edinburgh.

Colin Campbell leading the 'forlorn hope' at the Siege of San Sebastián, 1813. Painting by William Barnes Wollen

Colin Campbell leading the 'forlorn hope' at the Siege of San Sebastián, 1813. Painting by William Barnes Wollen© Wikimedia Commons

In 1689, Britain gained an Anglo-Dutch king, William of Orange or William III. He brought about 1,000 Dutch men and women to London to work at his court. His actions in Ireland gave rise to Orange being the colour of Irish Protestants. He gave his name to the town of Fort William in the Scottish Highlands, where he suppressed Catholic opposition to his rule. Native Britons learnt Dutch, too. The scientist Robert Hooke learnt the language so that he could read about scientific developments in the Dutch Republic such as those described by Anthoni van Leeuwenhoek, the discoverer of bacteria.

In the twentieth century, many Belgians sought refuge in Britain during the First World War. Dutch agriculturists went to Eastern England and introduced market gardening techniques. Few new Dutch words entered British English directly as a result of this contact, but some such as ‘cookie’ (Dutch koekje) have been adopted as a result of Dutch migration to North America. Large towns have Dutch communities. Dutch Studies at the University of London was celebrating its centenary in 2019 and in 2020 the Dutch church at Austin Friars in London will celebrate its 470th anniversary.

The Dutch church at Austin Friars in London

The Dutch church at Austin Friars in London© www.dutchchurch.org.uk

These days, some people in Flanders and the Netherlands are concerned about the increasing influence of the English language on Dutch. However, as this article reminds us, these two West Germanic languages have a long, shared history and each language owes a large debt to the other. It is to be hoped that this will not be forgotten and will continue to be the case in the future.