Moving Socially with Choreographer Mette Ingvartsen

For twenty years, choreographer Mette Ingvartsen has been creating socially and politically engaged performances. The key question she raises is whether we can create a world that revolves around joy and pleasure rather than repression of desires.

Mette Ingvartsen (b. 1980) extends her dancing to other artistic disciplines. Her creations form not only a permeable practice full of music, voice, technology and nature, but also encompass ethical issues, and everything you can imagine beyond just the physical movement. Her choreography is an awake and playful observation of the world and as a spectator you leave the space feeling good. Perhaps this is because her work embodies a desire for a more perfect reality? “Inventing possible realities”, is what she calls this herself.

Skating and dancing

It’s Tuesday, 9th of May 2023, in Paris. About an hour before the show starts in La Villette, a gang of Parisian skaters is taking in the stage. They have been permitted – even requested by the choreographer – to do this, because she wants them to experience what that smooth, light wooden floor with its perfectly calculated slopes feels like. It’s also a way of luring this young audience into the all too highbrow performing arts space.

In, 'Skatepark', Ingvartsen wants to create an exchange between skate clubs and a traditional dance audience

In, 'Skatepark', Ingvartsen wants to create an exchange between skate clubs and a traditional dance audience© Bea Borgers

When the music starts, the young skaters know they have to take their seats in the stands for Mette Ingvartsen’s new show Skatepark. Twelve other skaters and dancers between the ages of 11 and 35 have come to occupy their park on stage for an hour and a half. Some of them have only been skating for about a year, others have been moving on wheels for more than half their lives.

In Skatepark (2023), Ingvartsen does more than just investigate the flow and energy of these skaters. Beyond their acrobatic loops, she wants to show their environment. Her intention is to create an exchange between skate clubs and a traditional dance audience. Skateboarding is a very individual activity – you do it on your own. However, skating is very communal at the same time because you watch each other, learn from each other, share space and spend time hanging out together. It’s about control and freedom.

When Mette Ingvartsen takes something on, she wants to understand everything about it, and so she started observing the phenomenon in its social context. In Brussels, she went to the Ursuline skate park near the Brigittines Chapel. At first, she took her children, but later she visited the skate park alone. She observed for a very long time. Until she understood their behaviours, their agreements and their frictions.

In the show Skatepark, you immediately understand that agreements to avoid crashing into each other are of utmost importance. This is especially literal – you can see the skaters beaming as they slide past each other with extreme precision within a few millimetres. Ingvartsen became particularly intrigued by skateboarding as a counterculture, with its anarchic approach to public space and property. She also noted how this unusually heterogeneous community takes shape in an almost organic way – something she sees as a nice metaphor for Brussels, and for our whole reality.

Hiphop and ballet

Danish-born Mette Ingvartsen comes from a childhood of street dance herself. When she was nine, she started taking hip-hop lessons and very quickly became part of a group of young people who performed shows on the streets, in clubs, and at events throughout the city. An older leader of the group took care of the organisation and production of it all.

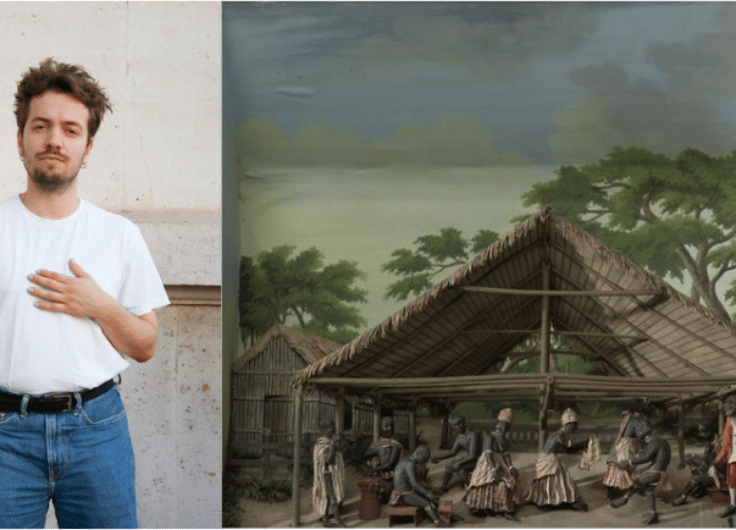

Mette Ingvartsen

Mette Ingvartsen© Bea Borgers

At some point, she remembers watching Janet Jackson dance amazingly to the music of “Rhythm Nation“, and in an accompanying documentary it sounded like you had to be brilliant at ballet if you wanted to be a real dancer. The young Mette therefore also decided to start ballet, in parallel with hip-hop. She found it terribly boring. However, there was a teacher from New York who taught (using) choreographer Merce Cunningham’s technique, and this was something that Mette became completely absorbed by. It opened up the more contemporary dance world for Ingvartsen. As a result, she became part of another junior ensemble, which focused more on modern ballet.

Because the dance school P.A.R.T.S. in Brussels wasn’t taking on any students in the year she wanted to start there, Ingvartsen ended up at the Amsterdam School of Dance. “There they only focused on body, body, body” she says. She did discover the work of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker there though. She found herself deeply impressed – a dance piece in which spoken word also featured! She also saw the theatre company STAN perform a piece that concluded with a string quartet and a stage emptied of people. She remembers thinking, “these are all things I want to do!” The training at P.A.R.T.S. that she received after her time in Amsterdam was thorough. Even before she graduated, she had performed at the Kaaitheater with her first creation, Manual Focus (2003), as well as founded her own dance company. She decided to stay in Brussels.

Malleable body

Mette Ingvartsen gets most of her ideas through reading and observing. Her work often stems from looking at things in the real world beyond the theatre walls, things she finds problematic or interesting – maybe both. She then tries to think about why she finds it problematic and/or interesting. “Reading – especially theory and philosophy – is a huge source of support and inspiration for me,” she says. This began during her time at P.A.R.T.S., where philosophy classes were included in the curriculum. She also likes to learn practices that have nothing to do with conventional dance, like stage fighting or the Lindy Hop (a type of swing dance). Her more traditional dance training plays little part in her work.

Two major themes characterise Ingvartsen's choreographic work to date - sexuality and the posthuman

For the first few minutes of Ingvartsen’s second performance, 50/50

(2004), it isn’t clear whether the audience is watching the back of a man or a woman. The bare, shaking buttocks and her large, broad-shouldered body deliberately sows confusion. Twenty years later, Ingvartsen explains she struggled with her somewhat masculine shape. It was disturbing at a time when concepts like transgender and non-binary didn’t really exist, at least not in the small town where she lived. Her early pieces were often about these concepts as a result.

She wanted to treat the body as a material that could be moulded and transformed. In 50/50 she takes on different roles – from rock star to circus clown – to mix up all the codes of the body. This is how her interest in identity and binary opposites arose. Much of her work is about overcoming the male-female, old-young, masked-naked divides.

In '50/50', Ingvartsen wanted to treat the body as a material that could be moulded and transformed

In '50/50', Ingvartsen wanted to treat the body as a material that could be moulded and transformed© Peter Lenaerts

This focus on the binary is systematically reflected in the two major themes that characterise her choreographic work to date – sexuality and the posthuman. In the latter, in her “natural” pieces, duality is represented through animate and inanimate, movable and immovable. Ingvartsen wants to know what that actually means. These are hardly self-evident subjects in the world of dance, where everything starts with the human body.

Ingvartsen developed the theme of sexuality in a series of pieces known as The Red Pieces: 69 positions (2014), 7 Pleasures (2015), to come (extended)

and 21 pornographies (2017). Each one deals with human achievement, focusing on nudity, sexuality and how the body has historically been a place of political struggle. She expresses this sexuality with remarkable coolness and detachedness in a triptych that is still regularly performed today: to come

(2005), to come (extended) (2017) and The Blue Piece (2021). In these three pieces, the dancers wear blue suits that cover the entire body (morph suits), so that the spectator can’t see their faces. It’s about erasing the features of masculinity or femininity – even if we see genitals or breasts. It’s also about erasing what we use to form identities: the characteristic looks, facial expressions, postures, and poses associated with different gender roles.

'The Blue Piece'

'The Blue Piece'© Lorraine Wauters

For Mette Ingvartsen, these pieces reveal a lot about power. Women are often seen as passive objects, including in sexual practices, but she believes that position can actually be reversed. As a result, she bases the entire choreography on converting a submissive into a dominant position. Everyone in the constellation can perform those dominant movements, regardless of sexual preference, or whether it’s a man or a woman. The series concluded with a series of conferences entitled The Permeable Stage, in which artists and theorists reflected on the politics of sexuality and how it moves across the boundaries between public and private space.

Another important part of Ingvartsen’s work is The Artificial Nature Series. In it, she elaborates on the relationship between the human and the non-human. In Evaporated Landscapes (2009), The Extra Sensorial Garden (2011) and The Light Forest (2010) not a single dancer is on stage. They are three choreographies without human presence. Confetti, gold-coloured emergency blankets, foam, smoke machines, leaf blowers and sound and light effects fill the scenes. These performances are quite dystopian, but strangely enough very beautiful and soothing to watch. A little like when we observe (real) nature – things changing slowly.

Mette Ingvartsen: 'If nature is in decline, we’ll have to create it artificially one day'

In Speculations (2011) and The Artificial Nature Project (2012), the human figure is reintroduced and intertwined with technological tools as well as the natural. A bit like real life, you want to think.

The most significant work within Ingvartsen’s performances about post-human reality is Evaporated Landscapes. She wanted to work with scenography made up of things that would disappear by themselves – this meant no wood or steel. She wanted to make people think about immaterialism in general, and so began with fog, foam, light and sound. She created a kind of miniature landscape in which the audience’s feet were covered in a low mist, with mounds of foam melting away. As a spectator, it first seemed like sitting on a mountain looking down, but over time you ended up beneath the clouds. The entire piece was all about the perspective from which we look – was it possible to create a performance from which people have been removed?

‘Evaporated Landscapes’

‘Evaporated Landscapes’© Tania Kelley

“Maybe one day we’ll have to create spaces where we can the calming type of experience that we’d normally visit nature for,” thinks Ingvartsen. “If nature is in decline, we’ll have to create it artificially one day.” It’s a very sad thought and a dystopian image in her otherwise rather optimistic work.

Dancing mania

With Skatepark, Ingvartsen’s choreographic work is now taking a new direction. The performances that Ingvartsen has developed over the past three years have no common subject. She’s looking for an expansive and “permeable” choreography. To this end Ingvartsen is observing movement within public spaces and the wider world – like skateboarding and patterns of migration, to try and understand what these movements express. She has also worked with performers of various ages who have not been trained as dancers.

For The Life Work (2021), Ingvartsen worked with Japanese women in their seventies and eighties who emigrated to Germany in their twenties. The piece is a collection of individual portraits, based on their personal stories. The Life Work was only shown during the Ruhrtriennale Festival of the Arts and was presented as more of an installation in a contemplative garden – although the Japanese women could also be seen live for a few weekends. In The Dancing Public (also 2021) Mette Ingvartsen dances solo, but in collaboration with the audience. She talks about the dancing manias that arose during the Middle Ages. The choreographer sees Skatepark

(2023) as a continuation of these approaches.

'The Life Work' is a collection of individual portraits, based on their personal stories.

'The Life Work' is a collection of individual portraits, based on their personal stories.© Katja Illner

Even if she starts from dystopias, what Mette Ingvartsen presents always contains a sense of reaching out to another reality or to a different kind of functioning. Despite the serious themes, her work is permeated with a certain positivism because she doesn’t give up hope in her creations. She frantically searches for possible alternatives, and hopeful perspectives.

Twenty years of creating also gives Mette Ingvartsen the feeling that she has been working for a long time – she has already made more than twenty pieces. But when she’s working on something new, it still feels like the first time. She’s celebrating those twenty years with Skatepark, because she feels too young for a book, and doesn’t want to record anything yet. She is also setting up a small retrospective with Manon Santkin, an outstanding performer who has appeared in most of her pieces and who has contributed enormously to her work.

Ingvartsen also wants to celebrate performance itself by exploring how Santkin succeeds time and again in transforming her body, like a chameleon. The two of them talk a lot about the role of imagination in memory and try to remember from where their previous works once grew. In this way, the dance fragments that they reuse can still tell us something today. They offer a look back at the past twenty years, which isn’t only important as a memory and a repetition, but they need to be interesting to watch today as well. “How can we rewild, become wild again?” Ingvartsen wonders. It characterises her tireless effort – she views artistic practice as a wilderness, as a continuously growing jungle through which she continues to traverse new paths. “What should you do to nurture your practice so that it continues to thrive?” She wants to find out.

She is far from done with it, the beautiful, sensitive Mette Ingvartsen.