Our Pride in Our Language Is Easily Hurt

A leaflet falls on my UK doormat: ‘Show your English pride!’, ‘English values, English History & English culture in our schools!’. In the paper, the British vox pop expresses its fear that ‘we will soon all be speaking German’. In the US, too, cars brandish bumper stickers with ‘We Speak English Here’ or ‘One Nation, One Language’, while their drivers wait for their president to ‘Make America Great Again’. These anxieties around the status of the language we speak, find a precedent in the nineteenth-century Netherlands.

In the nineteenth century, it was the idea of English, French or German linguistic dominance that went down badly with some of the Dutch. One of them was Marie Adrien Perk, brother of feminist Betsy Perk and a Protestant minister in Dordrecht. Although he may not have shared the political vision of the persons mentioned above, his sentiments were much the same.

Marie Adrien Perk’s pride in his Dutch mother tongue was hurt while in Switzerland. Drawing by Hendrik Haverman (1897).

Marie Adrien Perk’s pride in his Dutch mother tongue was hurt while in Switzerland. Drawing by Hendrik Haverman (1897).© Wikimedia Commons

During their centuries of economic prosperity, people in the Dutch Republic liked to think of Dutch as a biblical language, spoken in the days of the Old Testament or else a direct descendent of Hebrew or another classical language. Yet in the nineteenth century, with the Netherlands’ fall in international status and the simultaneous rise of comparative linguistics and historical thinking, the language’s close ties to German were increasingly emphasised and Dutch became classified as a ‘Germanic’ language; the Dutch people as a ‘Germanic’ tribe.

Although some scholars argued that in the great tree of languages, all branches were equally beautiful, an uneasy tension remained, both within and outside the learned community. The fact that the languages spoken by Netherlanders continued to be called ‘Lower German’ already suggests a painful inequality. Moreover, folk languages were still considered less valuable than the languages spoken by elites, such as metropolitan French, High German, or southern English. Not only were these latter ‘real’ languages spoken in the city, in contrast to the ‘dialects’ of the countryside, they were also used in writing – in literature, scholarship and law – and not ‘merely’ spoken. (Regional languages or dialects are often still approached with the same condescension today.) And now the problem turned out to be that, although the Dutch themselves were strongly aware of their urbanised culture and literary heritage, other Europeans did not necessarily share this knowledge.

Barbarians in the Pyrenees

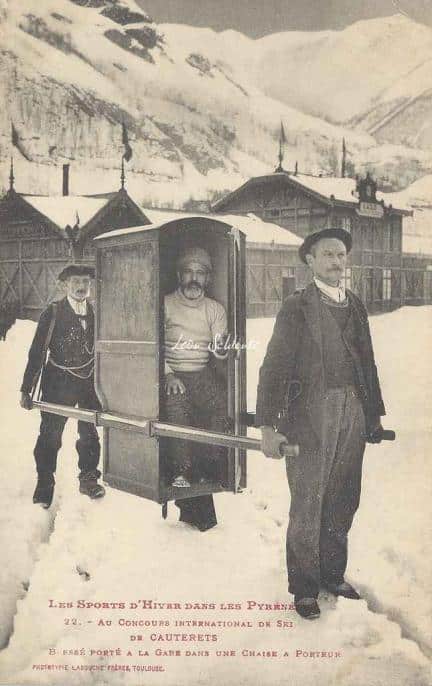

A photo of the kind of sedan Rees van Tets would have been carried in, and from the same region.

A photo of the kind of sedan Rees van Tets would have been carried in, and from the same region.© Labouche Frères

The idea that languages spoken by ‘the people’ were crude, simplified or unsophisticated variants of ‘proper’ languages was often expressed in travel writing. We see this in the diary of one Dutch traveller visiting the French Pyrenees. On 4 June 1819, art connoisseur and polyglot Henrica Françoise Rees van Tets-Gevaets was carried up the Gavarnie valley in a sedan chair. Her bearers spoke a Gascon ‘patois’. Not only does Rees van Tets use this pejorative term to describe their language, she also calls it ‘barbaric’ and likens it to the wild landscape she traverses.

A cheeky boy in Switzerland

1861: the tables were turned on our travelling Marie Adrien Perk. A teenage boy on a Swiss train wanted to know: “Where’s Holland? Isn’t that part of England?” Perk concedes in his account that these were unpleasant questions for a proud Dutchman to hear. After offering the boy a lesson in geography, he proceeded with a sample of the Dutch language. Another blow: “The lad deemed appropriate to judge that our language was merely a German patois! Brr!” Even after closer enquiry, “the boy remained adamant that we spoke nothing but a bastard German”.

Although Perk looked back on his encounter with some amusement, his pride was evidently hurt by this unsparing relegation of his mother tongue to the position of a rude dialect; and all this when the Dutch were already having to deal with the passing of their ‘Golden Age’. The protectiveness some Brits and North Americans today display towards the English language is a similar stage in a process of coming to terms with the fact that their country has lost or is losing its former political and economic leadership. The languages we speak are a vital part of ourselves and how we perceive them to be ranked among other languages can further damage an already shaken self-confidence.

Sources

- Henrica Françoise Rees van Tets-Gevaets, Voyage d’une hollandaise en France en 1819, M. Garçon (ed.) (Paris, 1966), 90-93.

- Marie Adrien Perk, Uit Opper-Italie [sic]. Schetsen, ontmoetingen, indrukken (Schiedam, 1864), 7-9.

- A highly informative and accessible book about the nineteenth-century politics of linguistics and more: Joep Leerssen, National Thought in Europe: A Cultural History (Amsterdam, 2008).