Poetry That Wants to Live

One hundred years ago, the Flemish expressionist poet Paul van Ostaijen wrote his masterpiece Bezette Stad (Occupied City). What does this old poetry collection still have to say to us in 2021? Dutch poet Iduna Paalman finds in the occupied city of Van Ostaijen the blueprint for the infected city of today.

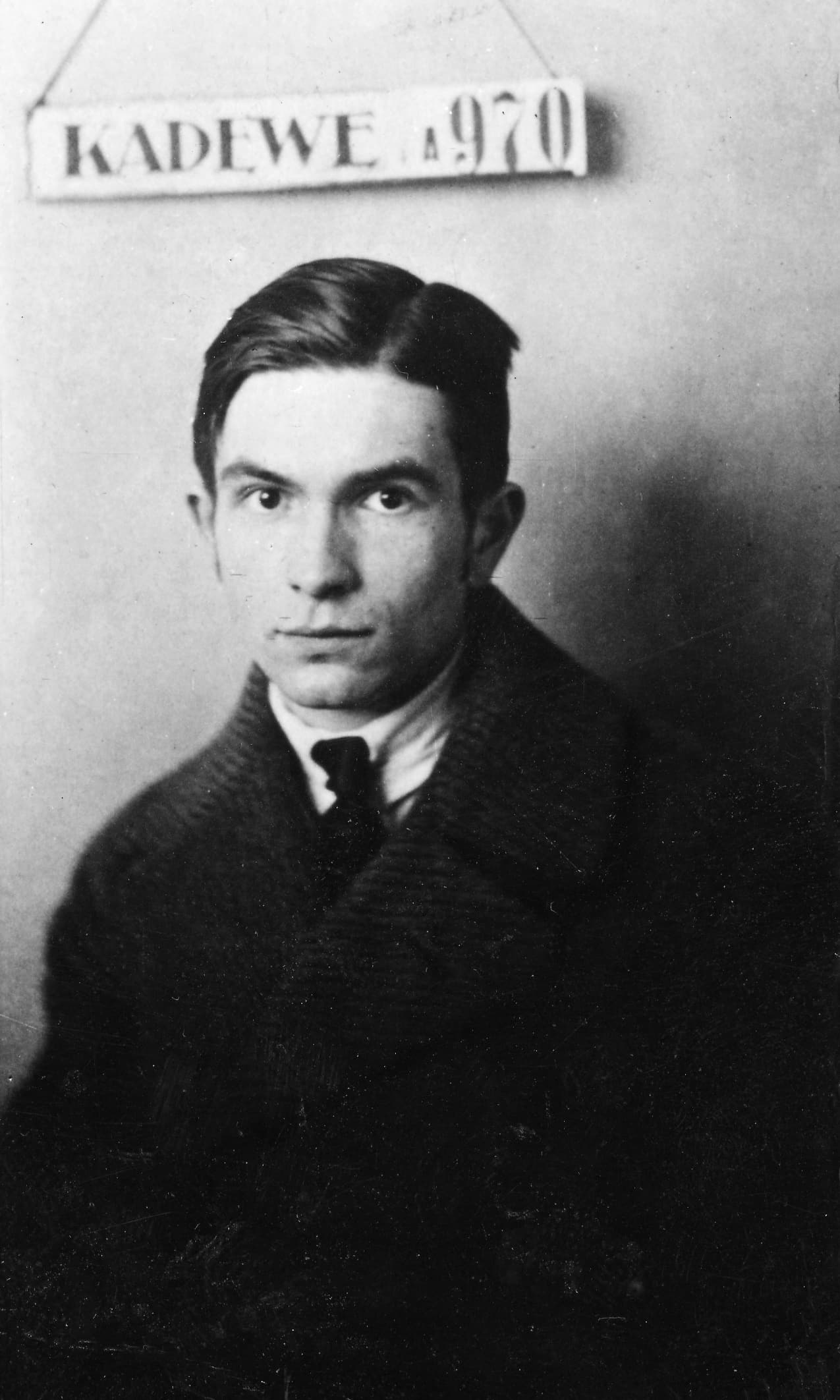

Paul van Ostaijen in 1918

Paul van Ostaijen in 1918© Letterenhuis, Antwerp

This is the nicest poem I know, says Mrs Van de Wal. She is a woman approaching sixty who generally has a wild look in her eyes, and I am someone who generally reacts fearfully to that. But today she seems mild. She has us twice a week for Dutch. Nice is a word she seldom uses, she doesn’t like making things easy for us. What do you want to know, she often shouts at us, well, come on, what do you really want to know for yourself? She once said to me that I would have a lot more going for me if I could finally get rid of that “damn shyness” of mine, and since then I try to ask searching questions and express my opinion. I don’t manage to, there’s a boy in my class who’s always one step ahead of me. Now too he asks the question that I wanted to ask: but what’s so nice about it, Mrs Van de Wal? About that poem? She does not look at him when she replies, she is not angry but her answer sounds as if she is giving us a punishment, as if the poem is doing something we are not: this poem is alive, she says loudly, it wants to live.

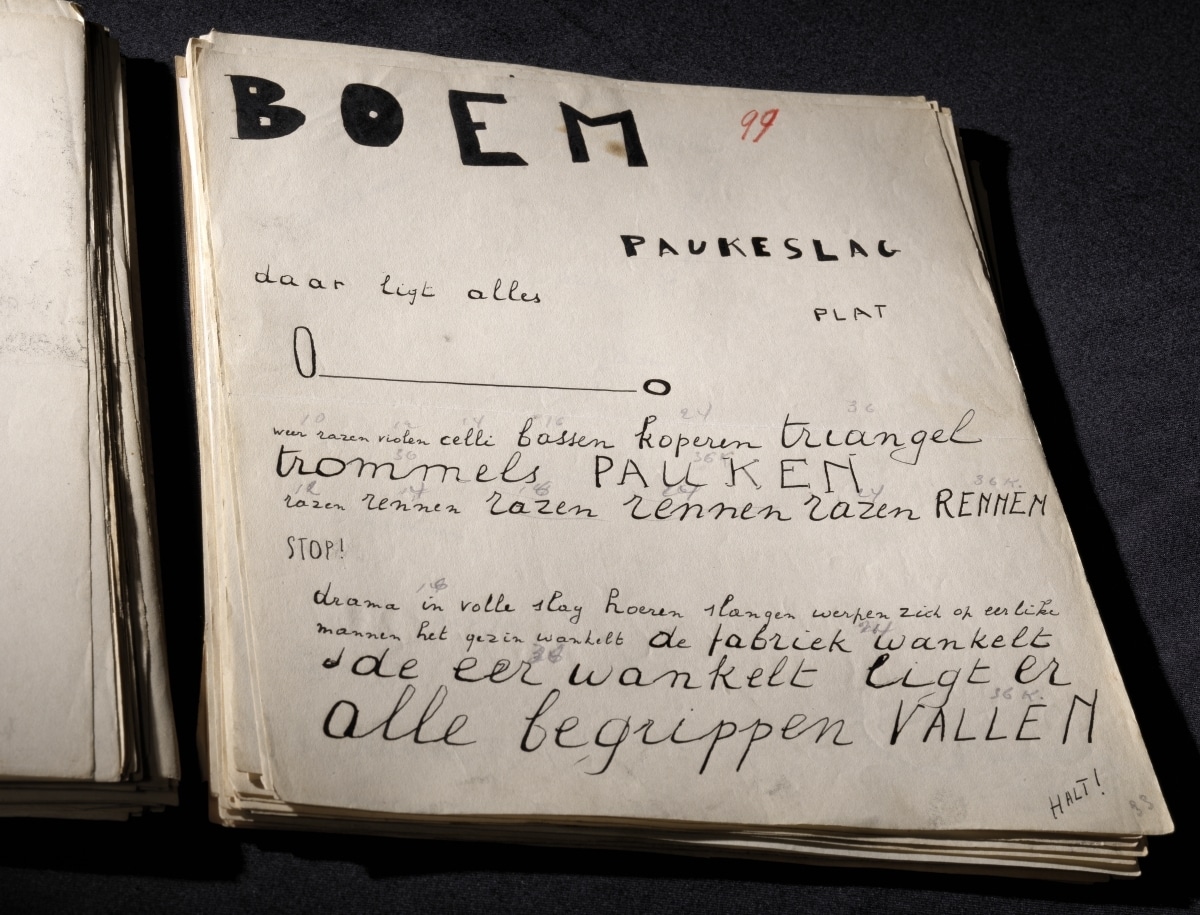

The original manuscript of the poem 'Boem Paukeslag' (Boom Kettledrum) by Paul van Ostaijen

The original manuscript of the poem 'Boem Paukeslag' (Boom Kettledrum) by Paul van Ostaijen© Bart Huysmans en Michel Wuyts

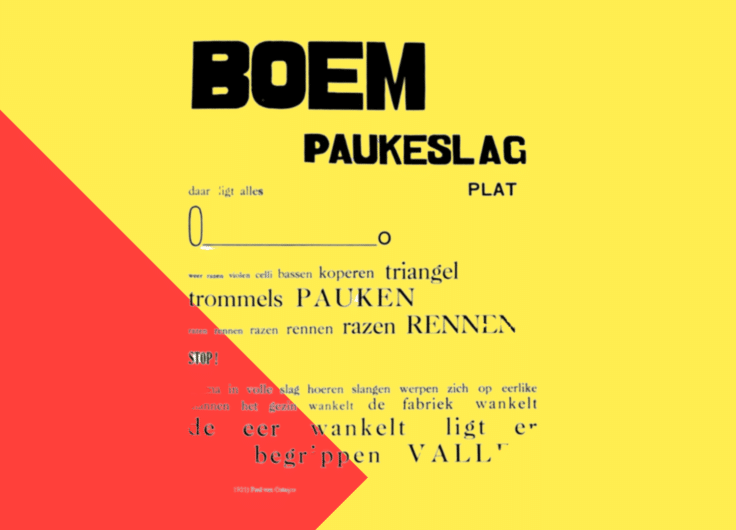

She is talking about Boem Paukeslag (Boom Kettledrum), Paul van Ostaijen’s iconic poem from his collection Bezette Stad (Occupied City), which was published a hundred years ago. What most readers of the poem remember is the striking typography, a welcome way in for lethargic teenagers. BOOM! says my teacher, we jump, look, she says, that’s what Van Ostaijen wanted. We mustn’t be lazy about reading, we must be alert! Rush run rush run rush RUN! Isn’t it unbelievably funny? Words that climb over a page like acrobats, sentences that roll and drum, the word zeppelin in the shape of a zeppelin, it’s all possible, it was all possible, it’s virtuoso stuff!

The word zeppelin in the shape of a zeppelin

The word zeppelin in the shape of a zeppelinAnyone reading the poems from Bezette Stad (Occupied City) will discover that the poet was not exactly cheerful when he wrote them. The First World War, which he spends in Antwerp, does not make him a hopeful person. His flight to Berlin, where he works on the poems in the post-war years, feeds both his cynical and his idealistic longing for a “new world”. That can be found in the poems, but I did not yet know that as a teenager. I make as a piece of homework for Mrs Van de Wal my own “concrete poem” in which the letters of the word rain stream down like raindrops from a cloud formed by the words condensed and moisture. I find it funny, but I don’t understand what she means by that “live”.

Oscar Jespers designed the cover of the poetry collection 'Bezette Stad' (Occupied City)

Oscar Jespers designed the cover of the poetry collection 'Bezette Stad' (Occupied City)© Letterenhuis, Antwerp

“Exceptionally well-known, seldom properly read and understood,” writes Erik Spinoy of Van Ostaijen’s poetry in the afterword to the recent new edition of Bezette Stad (Occupied City) published by Boom. In his collection, Van Ostaijen enters into a passionate dialogue with his own times, writes Spinoy, from an artistic and literary point of view, but also politically and intellectually. In doing he defines and redefines “his own identity both laboriously and restlessly”.

How do we recognise a new power of expression in poetry which until recently struck us as a grotesque formal experiment?

That should strike us as familiar. In an age in which social inequality, a widely embraced and among many young people quite natural activism, and a worldwide virus both unite and paralyse us, the poems of Bezette Stad (Occupied City) might acquire a new power of expression. But how do we recognise that in poetry which until recently struck us as a grotesque formal experiment?

Good News

Take the poem entitled Goed Nieuws (Good News), but which of course brings no good news at all. “Good news from the front”, is how it begins, but wasn’t all the news that came from the front bad news? “In many locations, the front scarcely shifted in four years of war,” writes Mathijs de Ridder in Boem Paukeslag (Boom Kettledrum), an impressive study of the poetry in Bezette Stad (Occupied City), which appeared at the beginning of 2021. “Where there were forced breakthroughs, it usually cost tens of thousands of lives.” So Van Ostaijen is being absolutely cynical in this poem and its lightness is deceptive. He seems

indifferent but meanwhile is sharply critical of all so-called “progress” in the war. “Those who in the circumstances maintained that they had nevertheless received good news, were exaggerating in Van Ostaijen’s eyes, or were disseminating pure propaganda”, writes De Ridder.

The poem 'Goed nieuws' (Good news)

The poem 'Goed nieuws' (Good news)In this poem, Van Ostaijen also deflates the myth surrounding the Belgian king Albert I: “the king alone in the trench/ Does he run away? A king doesn’t run away.” The king did not run away to England or the South of France, but stayed with “his” troops and had himself photographed repeatedly in uniforms, trenches and fighter planes. One big show, according to Van Ostaijen. Or as De Ridder writes: “In his eyes, Albert was no more than a spineless pawn of a propaganda machine that wanted to foist an image of Belgium on the population which had become very far removed from reality.” Anything but good news.

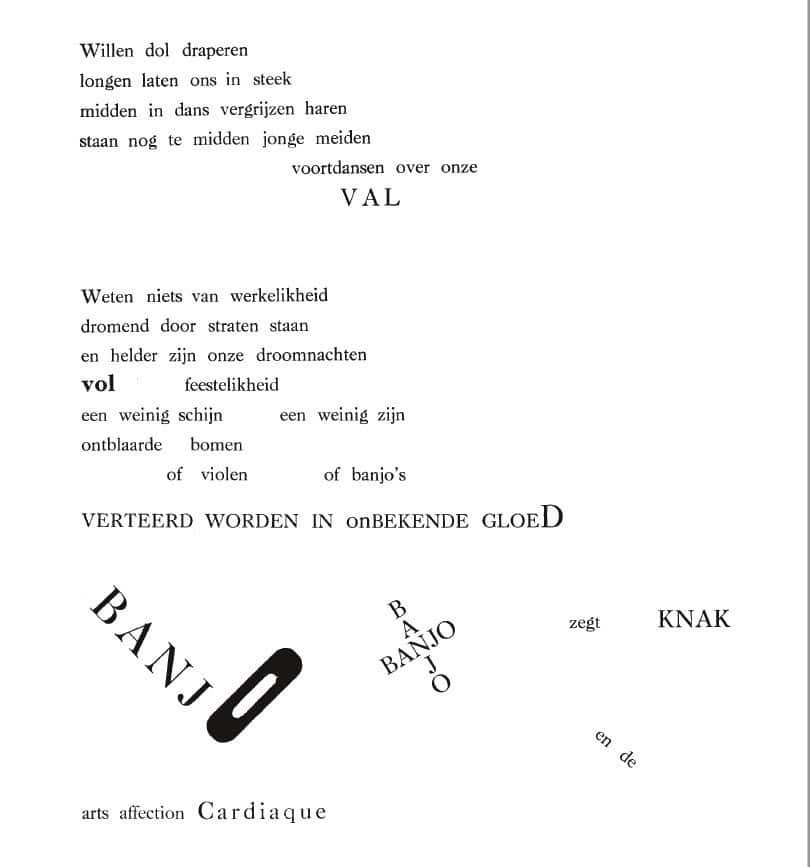

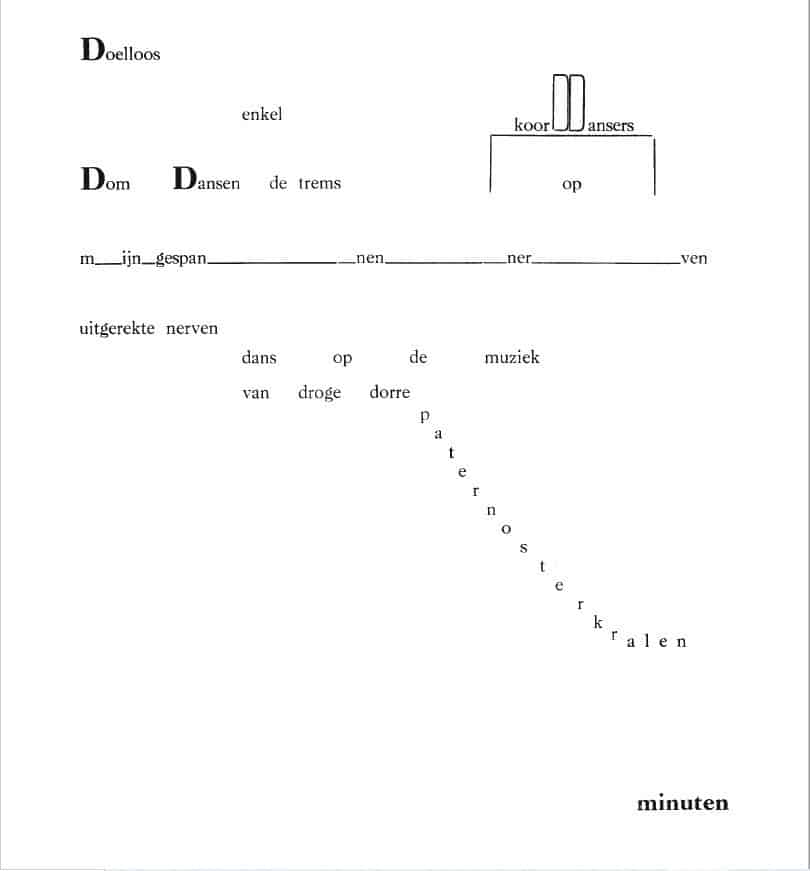

Just as in this poem Van Ostaijen seems to create a hopeful setting which subsequently turns out to be precisely the backdrop for disorder and insincerity, he uses this ploy frequently. In the poem Banale dans (Banal dance) there seems to be an excitement that we know from Boem Paukeslag (Boom Kettledrum). It almost sets the blood racing. “Life screams/ life grabs”, we read, “DANCE of desire”, “Want to drape crazily”, “bright are our dream nights / full of festiveness”. Is this the life that Mrs Van de Wal meant, banal dancing, moving and letting go completely? That letting go is only part of the story, writes De Ridder, a café is just a café and dancing here does not mean entertainment, just distraction from the inevitable “FALL”. “Lungs leave us in the lurch / in the middle of the dance hair goes grey”, writes Van Ostaijen later in the poem, and at the end the banjo says KNACK.

The poem 'Banale dans' (Banal dance)

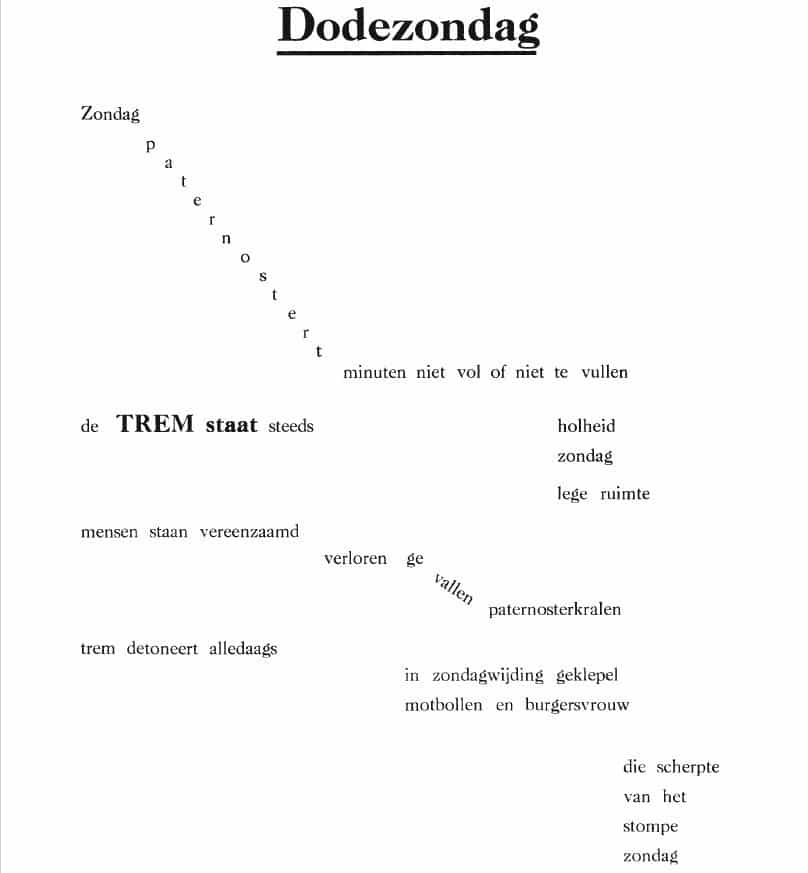

The poem 'Banale dans' (Banal dance)Can we find a glimmer of hope with Jesus then? Is he not the one with an answer in times of crisis? Oh no, not in Van Ostaijen’s occupied city. In the poem Dodezondag

(Sunday of the Dead) Van Ostaijen writes of “hollowness/ sunday /empty space”, and in Sous les ponts de Paris (Under the bridges of Paris) Jesus is “like a Harlequin”, and may bring consolation, but absolutely not salvation. “On top of the dike You keep watch with us, with chilly whores in the rainy night.” In this poem, Christ is close to the people, but precisely because of that affords little perspective. Or as De Ridder writes: “The real loser in the war was […] not this or that nation, but the poor soul who never asked for war and nevertheless has the suffering of all mankind loaded on his shoulders. Like Christ, in fact […].”

The poem 'Dode zondag' (Sunday of the Dead)

The poem 'Dode zondag' (Sunday of the Dead)Zeppelins, clowns, Silicon Valley

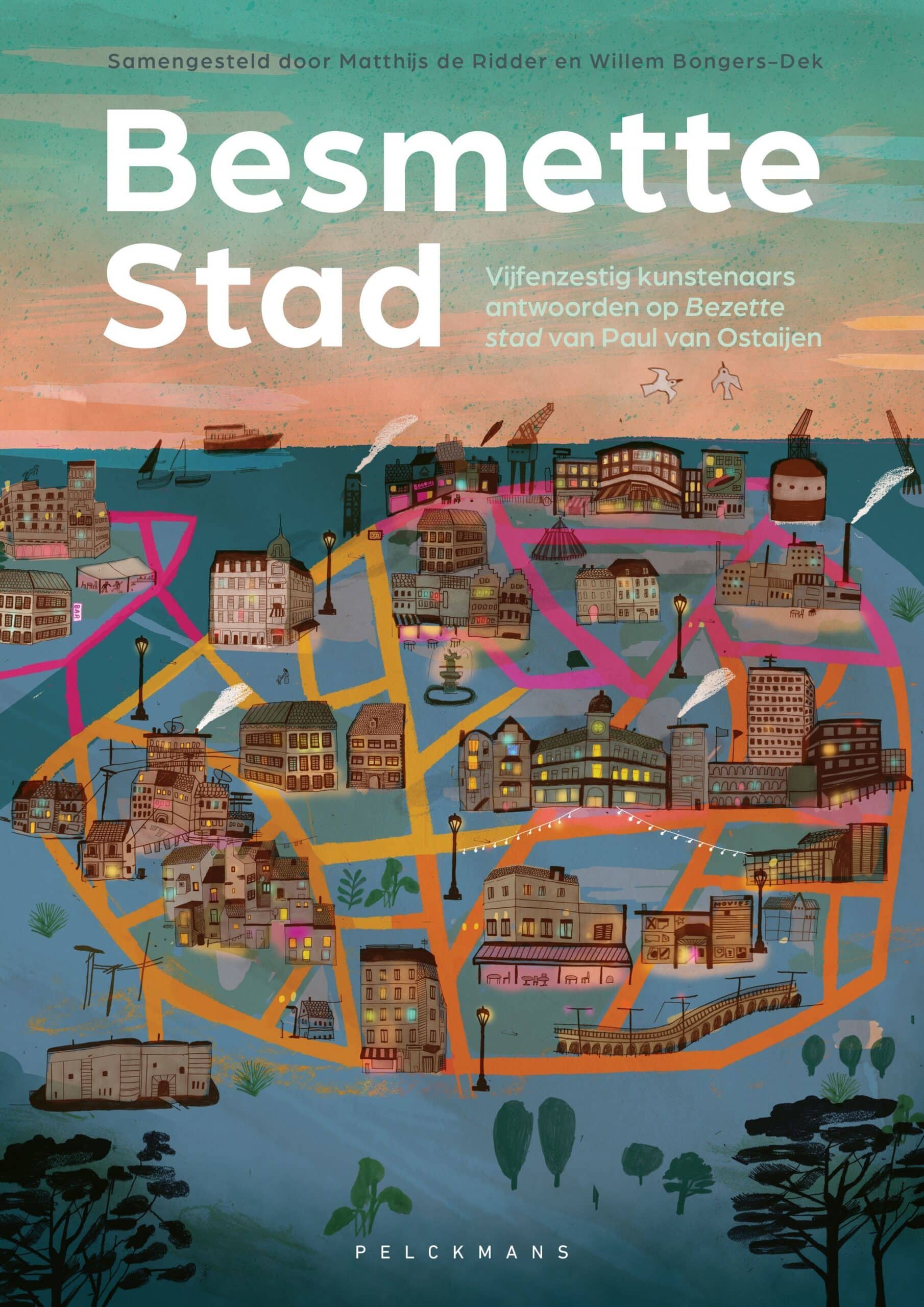

Poems that want to live and at the same time declare life bankrupt, that report on the oppression of an occupied city: what good are they to us in our present, in which a virus keeps us indoors? It took Matthijs de Ridder and Willem Bongers-Dek, director of Flemish-Dutch Huis deBuren, just a couple of texts and the idea was born: the occupied city became an infected city, in which over a hundred contemporary artists were inspired by Van Ostaijen and gave their own answers to his poetry. (I myself contributed the poem Projectieve meetkunde

(Projective Geometry).

Musicians Spinvis and Saartje van Camp reacted to Goed nieuws (Good News) with a musical performance, in which they begin as deceptively as Van Ostaijen can sound: “And when it was all over, people/ emerged cautiously from their houses. The streets looked/ like they used to. The trees, the birds, everything was/ still there”.

But all of that does not last long. Shortly afterwards a great shadow passes over the land “like a mighty hand”. The zeppelin is back. In the video that Spinvis and Van Camp made of their performance, we see “Good News” in thick red letters accompanying original war images in which the bodies of dead soldiers are carried into newly dug graves. Applause is inserted behind it. Later we hear Spinvis singing, in that appropriate light-hearted/serious way which we are familiar with:

Friends become strangers

No memory can keep up

And all the time you wanted to keep

Crumbles slowly in your hand

And blows out to sea

Lisette Ma Neza and Maja-Ajmia Yde Zellama responded to Banale dans (Banal Dance) with a video in which they tiktok, dance and say sentences like: “things we took for granted/ bodies that wash against each other without silicon valley” and: “reasons why we’re still dancing? / because we can’t help it/ because we know nothing/ because we’re young girls/ because we’re brown Mona Lisa girls/ because we are black girls from the Maghreb/ because we are Sub-Saharan African Muslim girls/ because we can’t help it”.

The illustrator Ward Zwart, who died last year, and to whom the book Besmette Stad (Infected City) was dedicated, drew in response to ‘Sous les ponts de Paris’ a dark and ghostly square in which large groups of people in Halloween-like dress are depicted alongside clowns, crosses, bones, dolls, churches and a large inflatable dinosaur. A yellowish light illuminates all the faces. This drawing seems to say: I don’t know what you’ve come for, but you won’t find reassurance here.

In this way, Van Ostaijen’s occupied city draws the map of our present infected cities. Not because the situations are the same – a war and a pandemic are fairly different – but because reactions to crises always show similarities. We seek for meaning in the face of the facts, have to make an extra effort to retain our sense of solidarity, long for a radical revolution. Can poetry be at the same time as helpless as it is hopeful, as unidealistic as idealistic? Can art be in-your-face and cynical in times of crisis, and have the impact of changing people for the better?

Can poetry be at the same time as helpless as it is hopeful, as unidealistic as idealistic?

Van Ostaijen’s “ideal poem”, writes Spinoy, is one that through its “visionary force and effective formal organisation has an impact on readers that goes beyond the individual and so is able to create a community of feeling.” Is that what Mrs Van de Wal meant by poetry that wants to live – texts that want to shake us awake, which bring together what has become fragmented, even if it is sometimes against our own better judgement? Both the occupied and the infected city leave this in no doubt.

Bezette Stad (Occupied City) has been translated into English by David Colmer in 2016.

Other translated work of Paul van Ostaijen can be found HERE.

These are the Dutch publications mentioned in the article.

. Paul van Ostaijen, Bezette stad, facsimile edition with an afterword by Erik Spinoy, Boom, Amsterdam, 2021, 160 pp.

. Matthijs de Ridder, Boem Paukeslag, Pelckmans, Kalmthout, 2021, 328 pp.

. Matthijs de Ridder and Willem Bongers-Dek (compilation), Besmette stad. Vijfenzestig kunstenaars antwoorden op Bezette stad van Paul van Ostaijen, Pelckmans, Kalmthout, 2021, 256 p.