Revulsion and Fascination: Hybrid Creatures in Visual Art

From medieval sin to modern climate catastrophe: in art, hybrids of humans, animals and objects confront the reader with the inconceivable.

Of course, my jaw dropped when I finally stood eye to eye with Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1480-1490), which brings together so many grotesque creatures. At the same time I was reminded of something I had read about the painting that had always stayed with me: all those strange creatures were once far less mysterious. According to art historian Nils Büttner, for contemporaries of Hieronymus Bosch (who lived approximately 1450-1516) the metaphorical aspect of these creatures would have been quite clear. Could that knowledge make this alien world more accessible? As a viewer today, it’s not so obvious what to make of features such as the bird with the back legs of a deer or goat, the two enormous human ears with a knife protruding from them, or a mermaid or merman covered from head to tail in a suit of armour. The latter is my personal favourite, as it sparks the imagination: what world and what battle has this figure run away from? Büttner labels the “monsters and hybrid creatures” as a “pictorial topos” of evil, further elaborating on this as follows:

The unnatural combination of flora and fauna […] has been interpreted as an indication of sin. The use of hybrid creatures carried to a fine art by Bosch, combining things drawn from nature to create monsters never seen before, was a well-known way of characterizing evil.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, central panel, circa 1480 and 1490. Bosch’s strange creatures bridge the distance between human and animal, resulting in a great deal of unease.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, central panel, circa 1480 and 1490. Bosch’s strange creatures bridge the distance between human and animal, resulting in a great deal of unease.© Museo del Prado, Madrid

Such background knowledge can be lost from collective memory, making such once-familiar images appear entirely mysterious. The rise and continued popularity of surrealism have also changed our view of Bosch. Painters such as Salvador Dalí are clearly indebted to him, which means he is often seen as a sort of proto-surrealist, perhaps leading people to interpret Bosch’s grotesque creatures as figures from dreams, hallucinations and other expressions of an individual subconscious. This makes Büttner’s account all the more interesting, as he implies that these hybrids are (also) representative of the Zeitgeist of the time: medieval society was religious to the core, with a major focus on the afterlife. A clear and terrifying image can incite extra piety. Nevertheless, Bosch’s creatures – even in his day – appear to have had a certain allure as well, perhaps somewhat like modern-day horror films which fill viewers with both revulsion and fascination.

Bosch’s creatures fill viewers with both revulsion and fascination like modern-day horror films

Why were those hybrids at the time a clear image of sin? Büttner does not go into detail on this point, but we can imagine a possible answer. Besides their grotesque appearance, there must have been something recognisable to the hybrid creatures; something all too familiar. In his much-cited essay, Why Look At Animals?, the British author John Berger writes about the “existential dualism” which characterises humans’ attitude towards animals: “[Animals are] subjected and worshipped, bred and sacrificed […] A peasant becomes fond of his pig and is glad to salt away its pork.”

The relationship between humans and animals was highly close over the course of the centuries, up until the Industrial Revolution. Still, there is also distance, Berger notes: “And yet the animal is distinct, and can never be confused with man.” Bosch’s strange creatures bridge that distance, resulting in great unease.

Human among animals

Art after Bosch was long characterised by a certain realism and recognizability. From the Renaissance to the Impressionists, there were few exceptions to that. That changed due to the rise of the historical avant-garde, beginning around the time of the Cubists. The alienation returned, thanks to movements such as Dada and Expressionism. Of all those movements, surrealism is probably the best known. In contrast with Belgium, the Netherlands never had its own branch of this movement, let alone producing an international star such as René Magritte, whose work also involved hybrids. For example, his Collective Invention (1935) presents the kind of mermaid you can expect from the teasing painter: a fish without a tail, but with a woman’s legs.

In the end, it turns out that surrealism – along with a number of shared sources, such as fascination with the mentally ill and children’s drawings – has a significant influence on the international Cobra movement, which also had a robust Dutch branch. The work of the Cobra artists is teeming with hybrids: between humans, animals, plants and sometimes even objects, namely masks. In contrast with Bosch (or Dalí), the style does not aim for any true-to-life look that might give the impression that these creatures could really exist. Cobra artists consciously painted in a raw, “primitive” style, in part because their sources of inspiration did the same. Many of their figures make a hybrid impression, but it isn’t easy to pin down precisely what is human or which animal is (approximately) being depicted. According to Cobra expert Willemijn Stokvis, the Cobra artists felt attracted to the animal world because they saw animals as higher than humans: animals were at one with nature.

Cobra artists saw animals as higher than humans: animals were at one with nature

Unlike with Bosch (who was also an important source of inspiration for this movement) the social context of the far more recent Cobra movement remains in the collective memory. Karel Appel, Lucebert and Constant wanted to work spontaneously, not least in response to the oppression of World War II. How was the world to move on after these major events? The Cobra artists, who were largely inspired by Marxism, had meanwhile developed the ambition of recreating society, with an emphasis on freedom.

A specific painting by Karel Appel (1921-2006), Man and Animals (1949), is interesting in this context. Although the title still suggests that man is not an animal, various creatures in the picture appear to be hybrid in nature. Yet the word and (it could have been with or among) suggests a certain equality. The owl-like and – I’m hazarding a guess here – the salamander-like figures appear to have arms rather than front legs, resembling the arms of the human in the picture. The human also wears a large mask, giving him an animal quality. That might well be the harmony with nature that the Cobra artists were searching for or in any case a depiction of their ambition in that direction.

'Man and Animals' by Karel Appel might show the harmony with nature that the Cobra artists were searching for.

'Man and Animals' by Karel Appel might show the harmony with nature that the Cobra artists were searching for.© Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam / Sabam Belgium 2023

Cold War

Another strong convergence between humans and nature can be seen in the sculptures of Lotti van der Gaag (1923-1999). Despite the clear parallels with Cobra, she has always been kept somewhat separate from that group. According to Laura Soutendijk, who along with Willemijn Stokvis campaigned for the restoration and re-evaluation of Van der Gaag’s reputation, her work is characterised by a “spontaneous manner of expression, appreciation of nature and material [and] primitive subject matter [which] ties in with post-war informal art”. Particularly in sculptures, which consist of a single figure, humans, animals and plants flow together. A beautiful example is De Denker (‘Thinker’, 1951), which is clearly inspired by Rodin’s famous statue but has an amphibian-like head.

'Thinker' by Lotti van der Gaag. In her figures one might discern mutants caused by radiation.

'Thinker' by Lotti van der Gaag. In her figures one might discern mutants caused by radiation.© Wikimedia Commons / Brbbl

For Van der Gaag, too, the “components” are not easily identifiable, because the imagery is intentionally quite unrealistic. Some of her more abstract sculptures even bear more resemblance to objects – possibly from another planet – than living beings. Soutendijk admittedly links this to the artistic climate of the time, including Cobra and innovations in sculpture, but she more or less leaves the political and social context out of the picture. She primarily sketches Van der Gaag as an artist working spontaneously, her pieces populated by fantastical creatures. World War II is barely mentioned, although the art historian acknowledges that these artworks can also be very frightening.

Those who look across the border will discover another link with Van der Gaag’s hybrids. The book Art of Another Kind (2012) parallels American and European developments in post-war art. In her contribution to the volume, ‘Abstract Sculpture of the Atomic Age’, art historian Joan Marter argues that the art of that period is too rarely viewed in the light of the Cold War. Marter notes a broader tendency for art historians to approach developments in sculptural art based on form, giving little consideration to the social context. She links the technological horrors of World War II – including the Holocaust and the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima – and hybrid creatures in sculpture. What should we make of David Smith’s Royal Bird (1947-1948), which explores the boundary between birds and military aircraft?

‘Dying Horse’ by Carel Visser is both an animal and an object.

‘Dying Horse’ by Carel Visser is both an animal and an object.© Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo / Sabam Belgium 2023

Marter does not deal with Dutch or Belgian examples, but the reader might be reminded of Van der Gaag, in whose figures one might discern mutants caused by radiation. Stervend paard (‘Dying Horse’, around 1949) also fits well into this context. The maker, Carel Visser (1928-2015), welded pieces of iron together, resulting in a caved-in horse with crab-like legs. The statue is both an animal and an object. The wide open mouth is also notably reminiscent of Guernica, putting the viewer indirectly in mind the atrocities of war.

Competition from objects

In today’s culture and society, roughly two movements of human-animal hybrids appear to be. Of course, there are anthropomorphic animals from comic strips and animated films, such as the ever-popular Donald Duck. Plush cuddly toys also often have something half-human about them, especially when they have two legs. They reduce the distance between humans and animals, without the unsettling effect of Bosch’s work. In contemporary art, mixed human-animal forms apparently still come across as grotesque and surreal. Animals have also encountered considerable competition from utensils. In the art of recent years – undoubtedly due to the influence of consumer society and technological developments – there are many human-utensil hybrids. For example, in the assemblage The Talebearer (2019) by Curaçaoan artist Tirzo Martha (1965), we recognise a head footer-style figure in the interplay of building materials. In various textile paintings by the Dutch artist Wouter Paijmans (1991) hooded jumpers with folded-out sleeves suggest human contours (as in Stars and Stripes, 2018, among others).

A hybrid creature can arouse contradictory emotions, reflecting the viewer’s frame of reference

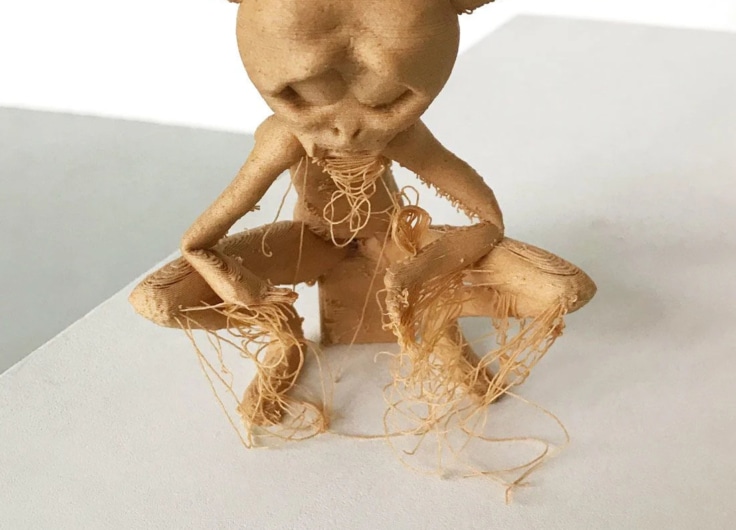

But despite the increased competition from utensils and inorganic objects, contemporary artists still use the animal as a “donor” for hybrid figures. The Moroccan artist Salim Bayri (1992), who works in Amsterdam, for instance, takes the anthropomorphic animals from animated films as the point of departure for the Mickey Mouse-like recurring character Sad Ali. This is an abbreviation of Sad Alien: a sad foreigner, migrant or extra-terrestrial being.

Salim Bayri takes the anthropomorphic animals from animated films as the point of departure for the character Sad Ali: a sad foreigner, migrant or extra-terrestrial being.

Salim Bayri takes the anthropomorphic animals from animated films as the point of departure for the character Sad Ali: a sad foreigner, migrant or extra-terrestrial being.© Salim Bayri

Bayri has emphasised on several occasions that this figure has no features. In an interview, for example, he said: “Sad Ali is […] empty, it doesn’t talk or say anything and has no agenda of its own. But it is there, and its presence is so vulnerable that it becomes the elephant in the room.” In the same conversation, he remarked that “Some people find [Sad Ali] scary, others see it as extremely sad.” That’s an excellent example of how this hybrid being can arouse contradictory emotions, reflecting the viewer’s frame of reference. The migrant background shared by Sad Ali and its maker also puts the viewer in mind the mixed feelings of recognition and alienation that different cultures can arouse.

Reaction to climate change

While in Sad Ali we can still recognise the “components” of human and mouse, other present-day hybrids are often harder to distinguish. A good example is Homo Stupidus Stupidus (2008) by Maarten Vanden Eynde (1977). This artwork is a human skeleton “assembled” in an almost animal-like manner, perhaps by archaeologists from the future, who have no idea of human anatomy. The post-apocalyptic mood is probably inspired by concerns over climate change, a central theme of this Flemish artist’s work.

‘Homo Stupidus Stupidus’ by Maarten Vanden Eynde is an almost animal-like manner, perhaps by archaeologists from the future.

‘Homo Stupidus Stupidus’ by Maarten Vanden Eynde is an almost animal-like manner, perhaps by archaeologists from the future.© Maarten Vanden Eynde

Similarly desolate is the sculpture Folly (2017) by Anouk Kruithof (1981). In her multimedia work this artist, who was born in the Netherlands and works internationally, focuses a great deal of attention on the relationship between humans and nature; specifically on pollution. Folly resembles a lump of inorganic material, partly covered as if the figure is hiding, with prosthetic legs on either side. Above all, these implements and their trendy gold trainers scream “human!”, whereas there is something animalistic about the legs’ horizontal shape and crab-like position. This is no longer a sculpture for the Atomic Age but for the age of climate change. Of course, it’s fantastic that prostheses exist, but in this case, they also contribute to pollution and to the post-apocalyptic look of the sculpture.

'Folly' by Anouk Kruithof is a sculpture for the age of climate change.

'Folly' by Anouk Kruithof is a sculpture for the age of climate change.© Anouk Kruithof

The hybrid figure functions in Kruithof’s work as a medium for mixed feelings – and in fact that’s not so different from the work of Bosch or Van der Gaag. Such works of art are exciting and imaginative, but they have an uncomfortable undertone. Every time there is a confrontation between recognition and alienation. That’s why these creatures are so well suited to statements about illusive themes: from deadly sin to devastating climate catastrophe.

Literature

- Tracey Bashkoff, Megan Fontanella and Joan Marter, Art of Another Kind. International Abstraction and the Guggenheim, 1949-1960, Guggenheim Publications, New York, 2012

- John Berger, Why Look at Animals, Penguin Books, London, 2009

- Nils Büttner, Jeroen Bosch: De schilder van visioenen en nachtmerries, translated byr Merel Leene into Dutch, Meulenhoff, Amsterdam, 2016

- Laura Soutendijk, Lotti van der Gaag, Waanders, Zwolle, 2003

- Willemijn Stokvis, Cobra. A History of a European Avant-Garde Movement: 1948-1951, nai010, Rotterdam, 2017

- Milo Vermeire, ‘Langs de ongrijpbare kern met Salim Bayri’, MisterMotley.nl, 9 november 2021