The Restless Spirit of Futurist Jules Schmalzigaug

Jules Schmalzigaug (1882–1917) fled Antwerp for Venice, Paris and The Hague, where his canvasses became spun with motion and imbued with colour. He was the first Belgian artist to participate in the Italian Futurist movement. At the age of thirty-four, the painter committed suicide, bringing an abrupt end to a promising career. With the publication of a lifetime catalogue, Schmalzigaug might be awarded more prominence in the canon of the Belgian and European avant-garde.

“Sickening, unenjoyable and impossible dilettantism.” This harsh judgement befell the paintings, pastels and drawings exhibited at the Spring Salon in 1923 by the Antwerp art group Art of the Present. The critic of Our nation viewed the works on show as “purely dynamic eccentricities that the devil himself had stared himself silly.”

This unnuanced response by a conservative reviewer is typical of the kind of reaction the work of Antwerp painter Jules Schmalzigaug, who had passed away five years previously, elicited. It is remarkable considering the fact that Schmalzigaug had been involved with the group since 1908, first as an “associated writer”, later as secretary. It might explain why attention for Schmalzigaug’s work didn’t gather momentum until late into the 20th century. His first monograph was published in 1984; solo exhibitions were held at the Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels in 1985, at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, also in Brussels, in 2010, and at the Mu.ZEE in Ostend in 2016.

Jules Schmalzigaug in Paris

Jules Schmalzigaug in Paris© Ronny and Jessy Van de Velde

Initiated by Galerie Ronny Van de Velde – a renowned private gallery in Flanders – this historical injustice has led to a beautiful double “book-in-cassette” publication. More than a hundred years after Schmalzigaug’s death, we now have a catalogue recording and presenting his complete works. It is accompanied by a biography by Peter J. H. Pauwels, in which he contextualizes the work and the man within the historical moment, as well as a text by Adriaan Gonnissen on the works produced by Schmalzigaug during his annus mirabilis. The catalogue continues the pioneering work of Valerie Verhack, who published the book Jules Schmalzigaug for the series Cahiers of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium in 2010. This formed the accompanying publication for the exhibition at KMSKB.

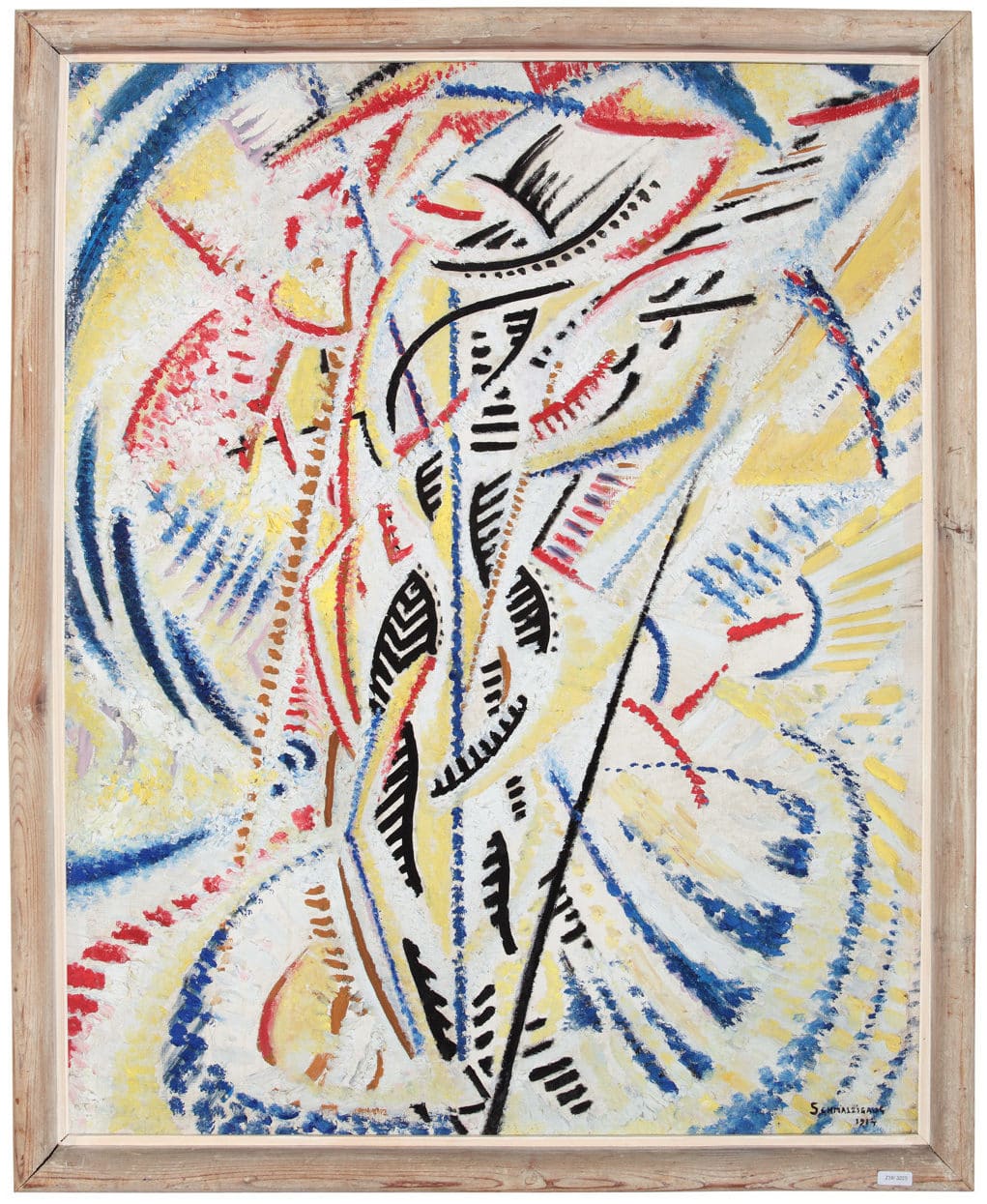

Jules Schmalzigaug, Colour organisation: Café - Concert - Surroundings, Venice, 1914

Jules Schmalzigaug, Colour organisation: Café - Concert - Surroundings, Venice, 1914Schmalzigaug lived his glory days in Venice and Rome during 1913-1914. He was one of the first non-Italian artists included in exhibitions of the most influential of avant-garde movements: futurism. The Belgian painter was represented through six works as part of the Esposizione Libera Futurista Internationale at Gallery Spronieri, from April to May 1914. Ever since 1912 he has been part of futurist circles and corresponded with several founders of futurist painting, like Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Ballà, whose ideas helped him hone his own artistic views.

His avant-gardism didn’t come naturally but was rather the product of a gradual evolution. Schmalzigaug was born into a middle-class, well-off environment. His father had become rich in the German coffee trade and, like many, had moved to Antwerp because of the economic possibilities associated with the harbour. Jules, the first born, later gained two brothers, Walter and Herman. His correspondence with them has been largely preserved and informed his biography.

In the refined and exclusively French-speaking, anti-clerical and liberal bourgeois environment he grew up in, a love of culture was assumed. A certain artistic sensitivity was instilled in him at home, but the first seeds for his future as an artist were planted during a health-retreat in Dessau, Germany. Schmalzigaug was born with a malformation in his vertebrae and would remain sickly his entire life.

Schmalzigaug fell in love with Venice and its “strange and phenomenal” light

In Dessau he met a teacher who recognized his talent for drawing. This professor, Paul Riess, would introduce him to the, mostly German, art of the time. Following his recommendation, he embarked on a year of study at the academy of Karlsruhe, where Hans Thoma, a painter Schmalzigaug admired, was the director.

Upon his return to Antwerp in 1905, Schmalzigaug invited Thoma for an exhibition in his hometown. That same year he had gotten involved in founding Art of the Present: a “network for the promotion of modern art” in Antwerp. The organisation did not only provide him with a meaningful position, but also with the opportunity to build and expand a wide, national and international network of artists.

Schmalzigaug called the Dutch "those people of shady character with heads like sheep and goats"

Even back in Karlsruhe, Schmalzigaug had realized that the work produced there was “more serious” than that at his hometown. His wealthy parents had, by this point, agreed to his desire to become an artist and would support him financially until his death. Every chance he got to explore the world he took. In 1905-1906 he made a trip through Italy, along with a friend, the painter Walter Vaes. The theatrical baroque aesthetic of Rome he deemed pompous, Naples was too dirty, but he immediately fell in love with Venice and its “strange and phenomenal” light.

In the following years, Schmalzigaug would travel between the cities he visited or lived in and his hometown. In the summer of 1906, returning home after his trip to Italy, Schmalzigaug visits the most renowned museums in The Netherlands. However, he does not like the Dutch. In one of his letters, he rages derogatorily against “those people of shady character with heads like sheep and goats, their cow-like appearance and their unpleasant language”. Nor can the Dutch in Flanders curry his favour – a possible explanation for why his work was little known in Flanders in the 20th century. As a francophone he does not usually find himself in Flemish-identified environments; as a cosmopolitan he couldn’t find a place in the Dutch history of art that was largely inspired by the ideals of the Flemish Movement.

After having been active in his art network a few years, and having written on exhibitions as a critic, often under the pseudonym Maurice Mandon, he found Belgian art meaningless and the Antwerp clique too smallminded. Paris was where it was happening: to Paris he went.

As a cosmopolitan he couldn’t find a place in the Dutch history of art that was largely inspired by the ideals of the Flemish Movement

Although the bustle of the modern city made an impression – the theme of art during the period – he kept feeling estranged from the French capital. He felt it was each to their own, but at least this feeling stimulates art.

Even though the city of lights offers him the chance to escape the dullness of Antwerp, the city that has the mind-numbing effect of a “sledgehammer blow to the head”, a city that “gelatinizes his brain”, he can’t escape his shielded upbringing. At salons, receptions and other social events he is like a fish in water; outside on the street the visible presence of the “lower classes of the population, the workers” who “behave like they own the street” frightens him.

He does work while there, paints, sketches, writes letters – and visits exhibitions, amongst which the famous Salon des Indépendants in 1911. There, in the now famous “hall 41”, cubist works have been displayed, one of the leading avant-garde movements at the time. Schmalzigaug was unimpressed: why remove any reference to reality?

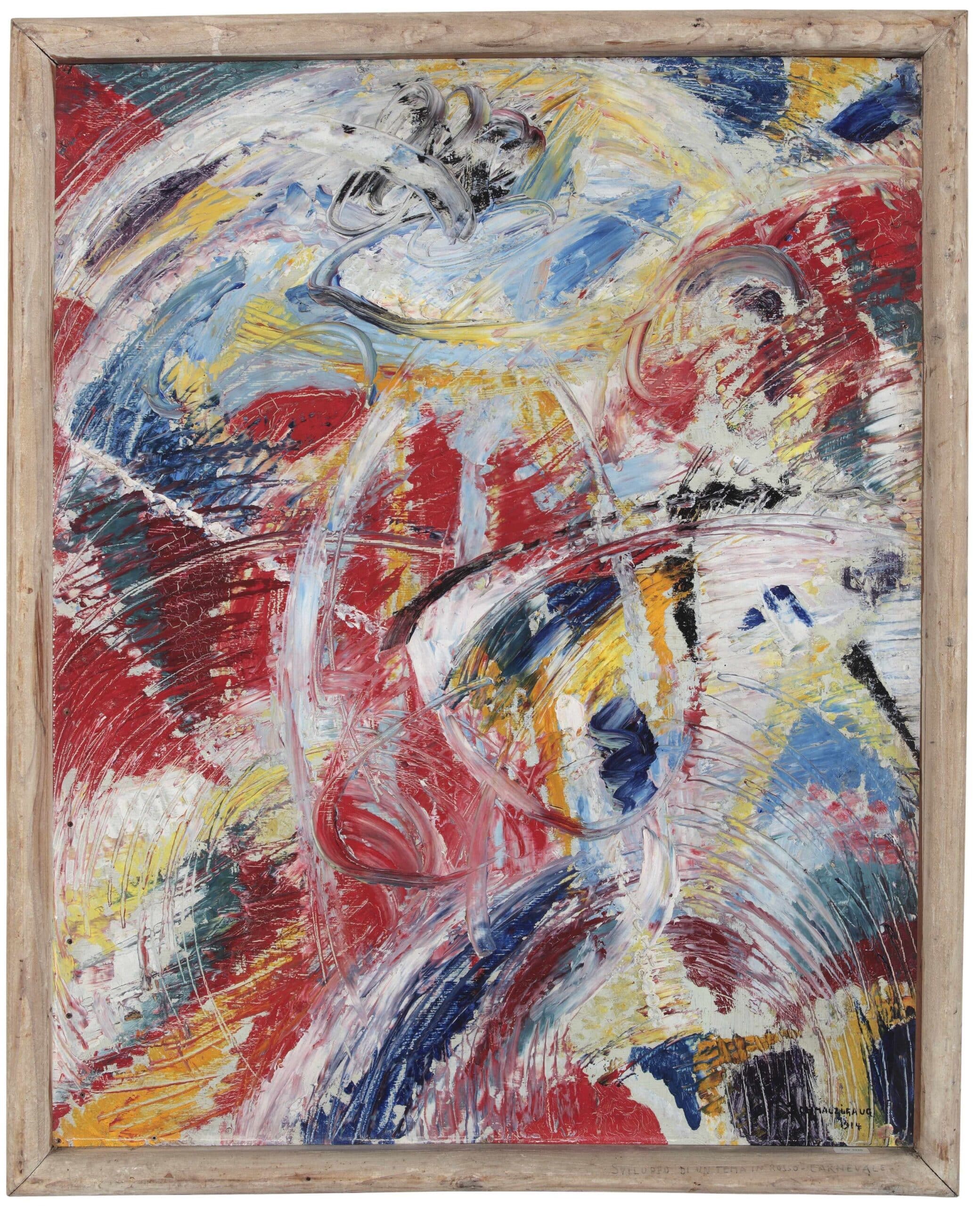

Jules Schmalzigaug, Development of a rhythm: Electric light and 2 dancers, Venice, 1914

Jules Schmalzigaug, Development of a rhythm: Electric light and 2 dancers, Venice, 1914How different was his introduction to futurism at the exhibition Les peintres futuristes italiens at gallery Bernheim-Jeune in 1912; an exhibition which would, in the months following, travel to countless European cities including Brussels, The Hague and Amsterdam, as futurism conquered Europe. According to Schmalzigaug, it was “unexpected painting” and “an enormous slap in the face of conventional thinking”. The ideas of leading figure Marinetti shocked the educated citizen in Schmalzigaug, but the futurist paintings fascinated the art lover in him, confused him, challenged him.

Still, he remains insecure about his own work while in Paris: “I have been educated by the best masters,” he wrote to his brother Herman. “Nevertheless, what purpose does it serve me? They who discovered those excellent formulas will always be more equipped to work with them than their students.” Did he feel he would, at best, only become a meritorious epigone?

In any case, these doubts made him decide to leave Paris and return to the city where he had been happiest: Venice. Immediately, he becomes more optimistic, more voluntaristic: he believes himself to be at the brink of a new step in his development. Through the relationship with the Italian futurists, but also through his visit at painter Jacob Smits’ studio in Kempen when he is briefly back in Belgium, his vision on the use of colour changes. His pallet, thus far relatively dark and influenced by the French painters of La bande noire, brightens, becomes lighter: the canvas has to become imbued with “its own luminosity”.

He describe the art in Belgium as a “nauseating vulgarity”

It isn’t until a year later, in the summer of 1913, that a real turning point manifests itself in his work. Under influence of the Italian avant-garde, he starts to approach the spiral as a new basic principle for painting, turning the painter into a “composer of coloured light”. At this point, Schmalzigaug had started sketching, drawing and painting out on the street. The light hitting the bell tower of San Marco, rebuilt just before his arrival, but also the interior of Café Florian, the movements of dancers, the crowd in a music hall. His aversion to Belgian art grows, describing the art in “that country of pastors and gin” as, according to his aesthetic ideas, being of a “nauseating vulgarity”.

Jules Schmalzigaug, Gold + Flags + Parasols: San Marco Square, 1930

Jules Schmalzigaug, Gold + Flags + Parasols: San Marco Square, 1930When, in 1914, he becomes one of the few foreign artists allowed to exhibit six paintings as part of an important futurist exhibition in Rome, he might have finally felt himself to be the cosmopolitan artist he had longed to be. His canvasses spin with movement and are imbued with colour, like those of his Italian peers and friends. Increasingly, he shapes his ideas on art according to avant-garde examples: what is currently viewed as fine art painting, he writes his brother Walter, will soon be old news. A painter should no longer paint on canvas, but “write partitions of colourist orchestration”. The painting Gold + Flags + Parasols: San Marco square, exhibited in Rome, represents Schmalzigaug’s evolution beautifully.

Where first he put impressionist depictions of Venice into thick layers of paint, this work emphasizes in bright colours the dynamic elements that make up the scene. The painting is actually “two works in one”, so writes Adriaan Gonnissen: an impressionist cityscape and a futurist study of colour and movement. A different work, also shown in Rome, Development of a theme in red: carnival, shows how far Schmalzigaug had come in the futurist doctrine in a short amount of time. Gone is any representation of reality. The canvas has become a composition in which colour and movement are the only constructive elements. According to Gonnissen, this work is nothing less than the first completely abstract painting by a Belgian artist – another reason to assign its maker an important place in the history of Belgian art.

Jules Schmalzigaug, Development of a theme in red: carnival, 1914

Jules Schmalzigaug, Development of a theme in red: carnival, 1914However, at the end of June 1914, a Serbian student shoots the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand. One month later, Europe is at war; Schmalzigaug leaves Venice and returns to his homeland. On the 10th of October Antwerp surrenders to the German conqueror. Schmalzigaug’s family leaves for The Hague, where a large Belgian colony attempts to escape the violence; Schmalzigaug follows, and moves into his own flat in the Van den Spiegelstraat.

There, the fairly active Comité belge de La Haye founds a school for decorative arts in order to properly train Belgian girls in exile. In his courses on art history, Schmalzigaug emphasise is the battle against academia. Cézanne and Ensor are given an important role in it. And Schmalzigaug’s vision on art history is clearly expressed. There are roughly, so he says in the course, two types of artists: cherchants or seekers, and exécutants, performers. The first type of artists has the power to pre-empt the future, the latter merely continues achievements of a past generation.

Surplus to teaching, Schmalzigaug continues to develop his artistic practice. In The Hague he develops his own theory of colour. The tract La Panchromie is presented for the first time in this catalogue. La Panchromie is a manifesto of twelve rules of modern colour usage, with which you can create contrast or balance. It was never published and only one meagre copy survives but, nevertheless, it is an important historical document.

Jules Schmalzigaug, Portrait of baron Francis Delbeke, 1917

Jules Schmalzigaug, Portrait of baron Francis Delbeke, 1917Even though Schmalzigaug’s ideas were inspired by an older, British theory of colour, La Panchromie is a rare and early example of an artistic foray into colour usage exemplary of the search for new styles, methods and shapes in the early 20th century. Johannes Itten’s theory of colour, taught between 1919-1922 at the Bauhaus in Weimar, and later written up as part of Art and Colour, may be the most famous example. It is taught until this day to art students.

Besides studying and theorizing, Schmalzigaug kept sketching, drawing and painting while living in The Hague. As an extension of La Panchromie he did colour research, made a couple of futurist canvasses, painted cityscapes, portraits and still lives and sketched numerous scenes of city life and the Scheveningen beach. Three of his works were shown at the exhibition Belgian Art at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam – however, they did not invoke a critical response.

This impression by Jan Greshoff, then the art editor for the daily newspaper The Telegraaf, whom Schmalzigaug must have met somewhere in The Hague, summarizes how people thought about him and his work. Greshoff was struck by Schmalzigaug’s “soft, slightly veiled and monotonous voice which imbued every word with mysterious, suggestive power”. As a person, Schmalzigaug made a “driven” but “nervous” impression. His work, however, was seen by Greshoff (and many others) as “confused and far-fetched”.

During the severe winter of 1916-1917, Schmalzigaug’s physical health deteriorated significantly, after having indicated previously that he suffered from “mental neurasthenia” in the in no way quiet city of The Hague. On the 12th of May 1917, Schmalzigaug killed himself in his apartment. No letter was found, nor any clear explanation. Could it be that he, due to the lack of or negative responses to his art, had come to the conclusion that as an artist he was not a chercheur but an exécuteur? And was he right?

Although this qualification may have been useful at the time, whoever flicks through the complete works of Schmalzigaug today cannot see but a trying spirit, continually searching for freedom and self-improvement, led by ever-changing masters; who was grateful for his heritage but had great difficulty developing himself in the long shadow it cast.

Schmalzigaug’s role can be compared with that of his successfully canonized city- and generational peer Paul van Ostaijen

Maybe through this catalogue, its material as complete as possible, the facts and works known, his name can be given more prominence in the canon of Antwerp, Flemish, Belgian and European avant-garde. A movement in which he may not have played a historical role as a leader, but most definitely was a seeker, and certainly achieved more than an exécuteur. It remains curious that a private gallery, with the support of Schmalzigaug’s family, has taken on this art-historical work. Shouldn’t it be the task of the government, or trusted institutions and museums, to do this kind of foundational historical research and publicize its findings? Or are these by this point so underfunded that only those with capital, those private agents, are capable to do what an art-loving government is supposed to?

Because maybe, taken into account all the characteristic and ideological differences, Schmalzigaug’s role can be compared with that of his successfully canonized city- and generational peer Paul van Ostaijen (1896-1928): one of the frontrunners in his discipline, who invited international trends from a new era into a sleepy, complacent country caught still in the past.

Jules Schmalzigaug 1882-1917, Galerie Ronny Van de Velde, Antwerp & Ludion Publishers, Brussels, 2020, 2 volumes in a slipcase, 824 pages. The first volume, authored by Peter J.H. Pauwels, is a monograph that sets Schmalzigaug’s work in the context of the European artistic movements of his time. The second comprises the first catalogue raisonné of his oeuvre in its entirety.