When Painters Go Ice Skating

Although the Dutch have been ice skating since the thirteenth century, it was not until the sixteenth century that ice skaters would regularly appear in paintings, courtesy of the Flemish Master Pieter Bruegel the Elder and… a climatic phenomenon. Since then, countless artists have ventured out onto the ice and the (self)image of the Netherlands as a skating nation has emerged.

Depictions of ice skaters can be found early in the fine arts of the Low Countries. In the fifteenth century, ice skaters pop up with some regularity in depictions of the winter months in books of hours. In addition, in De Tuin der Lusten (The Garden of Earthly Delights) and the Antonius-triptiek

(Anthony-triptych), both painted by Jheronimus Bosch, you can see demons and monsters here and there on narrow skates, as well as lone ice skaters in a frozen scene from hell. The people are not having fun on the ice, which, entirely in the spirit of Bosch, is consistent with the widespread idea in the Middle Ages that freezing temperatures were the work of the devil and also gave rise to danger.

Sixteenth century: Pieter Bruegel

The genre of more peaceful winter scenes with ice skaters – in the tradition of the miniatures in breviaries – only really blossomed in the middle of the sixteenth century, and especially through the efforts of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. One of his most famous works is undoubtedly Jagers in de sneeuw (Hunters in the Snow, 1565), which is part of a series of six panels each depicting two months of the year. The work is one of the first paintings where a painter fully succeeds in convincingly depicting the bitter winter cold and the variations and shades of snow and ice. To the right of the painting, numerous villagers can be seen swaying on the ice or practicing various (ball) games with their skates strapped on.

Bruegel’s ‘Hunters in the Snow' is one of the first paintings where a painter fully succeeds in convincingly depicting the bitter winter cold and the variations and shades of snow and ice

It is no coincidence that precisely in the 1660s the winter scene gained enormous popularity and become its own genre in the fine arts. There were several exceptionally harsh winters in that decade and as a result, broad rivers directly connected to the sea (such as the Scheldt) froze over for weeks if not months. Ice and thus ice skaters were explicitly present and visible in Antwerp and other cities at the time. This was the direct result – after a hesitant start in earlier decades – of the onset of what was known as “the little ice age” in northwestern Europe, which would last until approximately the year 1700. In addition to relentless fun in the snow and on ice, there were more dramatic consequences such as crop failures, famines and deaths, which were (partly) the cause of social disruption.

Women were held accountable for the deterioration of climatic conditions and any additional adverse impact

Quite convincingly, research in recent decades has also linked the onset of the little ice age to the simultaneous sudden and fierce increase in witchcraft in the Low Countries. Women were held accountable for the deterioration of climatic conditions and any additional adverse impact. The extreme cold and the joy of ice and skating had their downsides. Coincidence or not, Bruegel also initiated a number of iconographic traditions in the genre of witchcraft scenes that, similar to winter scenes, had a great influence until after the mid-seventeenth century.

Several of Bruegel’s winter scenes depict skaters; this is most prominent in the engraving Schaatsers voor de Sint-Jorispoort in Antwerpen (Skating before the Gate of St. George in Antwerp, c. 1558), carved in copper by Frans Huys to the design of Bruegel and printed and published in vast numbers by Hieronymus Cock. It is possibly the earliest work in which skating is really the main subject, with many endearing details such as a man supporting his ice-skating wife around her waist, the group on the right strapping their skates on, and (judging by the outfit) someone wealthy from Antwerp allowing himself to be pulled forward (by a servant?).

Skating before the Gate of St. George in Antwerp, c. 1558, engraving by Frans Huys to the design of Bruegel. It is possibly the earliest work in which skating is really the main subject.

Skating before the Gate of St. George in Antwerp, c. 1558, engraving by Frans Huys to the design of Bruegel. It is possibly the earliest work in which skating is really the main subject.© Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp

Remarkably, a few years later the Venetian publisher of prints called Ferrando Bertilli had a mirror-image copy of Bruegel’s print engraved. It is one of the rare times in Italian art that skaters have been depicted so explicitly. The poem under this copy also speaks with some surprise about the natural phenomenon of ice. Understandable, as the canals of the City of Doge must not have frozen over very often, and skaters were thus fairly uncommon.

No less fascinating is a republication of Bruegel’s skating scene in the mid-seventeenth century. Dutch verses are added here that give a moral meaning to skating, in particular ‘de slibberachtigheyt van ’s menschen leven’ waar ’D’een stronckelt, genen valt’. Mensen zijn als schaatsers en wij’ slibberen onsen wegh, d’een mal en d’ander wijs; op dees vergancklijckheyt veel broser als het ijs’ (the slipperiness of human life where one stumbles, sometimes falls. People are like skaters and we navigate ourselves, one silly and the other wise; on this impermanence much more brittle than the ice’.).

A thought that may not often come to mind when we see Sven Kramer and other speed skating stars prevail at the Winter Olympics. Although ultimate glory and dramatic loss can alternate over there as much and as quickly as they did for the Antwerp citizens skating around the then brand-new city ramparts: note the fallen skater who is handed a helping hand or, even more naively, the man to the left of the gate who has already tumbled into a hole while skating.

Seventeenth century: Hendrick Avercamp

After the advent of Pieter Bruegel, there was not much attention paid to the winter scene in the southern Netherlands and the genre of winter landscapes with ice skaters became entirely a “Dutch thing”, as is often suggested in the literature. However, that proves to be demonstrably false. In the wake of Bruegel, quite a few painters in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries ventured into the subject, see for example the works of Abel and Jacob Grimmer, Joos de Momper and Bruegel’s son Pieter the Younger.

Flemish painters are supposedly the ones who introduced the theme to the North. Prints after Bruegel, as well as a stream of painted copies of his work from 1600 onward, are widely available in the northern Low Countries. After the fall of Antwerp in 1585 during the battle against the Spaniards, there was a massive influx of Flemish Masters to the north, particularly in Amsterdam. Among them were Gillis van Coninxloo and David Vinckboons, both acclaimed landscape painters who also painted winter landscapes in the manner of Bruegel.

Hendrick Avercamp – the painter who is often associated with winter landscapes with ice skaters in the seventeenth century – learned the same skills from these masters. In the Netherlands, many will consciously or unconsciously know his Winterlandschap met ijsvermaak (Winter Landscape with Ice Entertainment, 1608) from the Rijksmuseum, because this is a well-known image that is sealed on cookie jars, mugs, diaries and other merchandising.

Hendrick Avercamp, Winter Landscape with Ice Entertainment, 1608. Avercamp’s scenes are an attractive mixture of vast landscapes and much anecdotalism, based on the Flemish Bruegel tradition.

Hendrick Avercamp, Winter Landscape with Ice Entertainment, 1608. Avercamp’s scenes are an attractive mixture of vast landscapes and much anecdotalism, based on the Flemish Bruegel tradition.© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Hendrick Avercamp is also known as ‘the mute of Kampen’, a nickname he was given because he was mute and grew up and worked for a long time in this city in Overijssel. The pharmacist’s son was trained as a painter in Amsterdam, where Vinckboons and Coninxloo familiarized him with the new genre of winter scenes in Bruegelian style. Avercamp would make it his trademark. Moreover, it is said that he himself was a great lover of ice and skating.

Avercamp’s scenes are an attractive mixture of vast landscapes and much anecdotalism, based on the Flemish Bruegel tradition. Skaters everywhere in all shapes and sizes, positions and ranks, mixed with other reckless others wobbling on ice without narrow blades. As with Bruegel, kolf players are also often seen on the ice in Avercamp’s paintings – an early precursor to croquet. Ice hockey is still a long way off.

Characteristic of the genre is that the winter scenes always take place where city and countryside meet

Characteristic of the genre is that the winter scenes always take place where city and countryside meet. This is not strange as in these cities there were enough inhabitants to fully discover the fun on ice, and virtually all Dutch cities – like the Flemish ones – were surrounded by ramparts with canals connected to many rivers and other waters surrounding rural areas.

In the wake of the Flemish Masters, Avercamp became the figurehead of a genre that was rapidly gaining popularity in the northern Low Countries in the first half of the seventeenth century. His much younger cousin and pupil Barent also specialized in painting ice scenes. Other (landscape) painters such as Adam van Breen, Aert van der Neer – also known for his other speciality, the nocturnal moon landscape -, Anthonie Verstraelen and Jan van Goyen combine winter scenes with ice skaters and with other types of landscapes.

There must have been a great demand, and not only in painting. In a striking variation of the also very Dutch proverb ‘he who does not honour small things, is not worthy of great things’, skaters are particularly popular subjects on the (hand)painted so-called Delft tiles that were mass-produced in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Although paintings were part of the everyday environment of many homes more than we often realize, this is even more true for the widely produced tin-glazed pottery. Skaters were not only part of the (city) scene in the Dutch republic for several weeks or months each year, but images were also ubiquitous. This indeed creates the painted (self) image of the Dutch republic as a nation that is crazy about skating.

Delft tile, seventeenth century

Delft tile, seventeenth centuryThe ‘average’ ice scene in the seventeenth century remains more or less rooted in the Bruegelian tradition canonized by Avercamp – a vast frozen landscape with a motley mixture of citizens and villagers, skating, walking, falling, scribbling or playing kolf. Attractive and recognizable to many, but also generic as well as repetitive and clichéd. What is striking here is that specific towns and cities are regularly recognized topographically, with places as diverse as Amsterdam, Oudewater, Kampen, Zutphen or Leiden, to name a few. It must have been this mixture of recognizable human wriggling with equally recognizable buildings from one’s own urban environment that made the genre so attractive to the Dutch bourgeoisie.

One last observation: the winter landscape follows the general development of landscape with a more pronounced high horizon at the end of the sixteenth century to a lower horizon, often also somewhat less extensive in the course of the seventeenth century. Jan van Goyen exemplifies this most clearly.

The landscape becomes more prominent

The eighteenth century was to a large extent a continuation of the traditions of the previous century. During the nineteenth century, the landscape was particularly popular as a subject, and a striking change also occurred in the depiction of the winter landscape from the Romantic period onward. The fascination for frozen waters with skating compatriots remained and numerous important and influential painters ventured into the subject, but the anecdotal and the universally human aspect disappeared entirely. The focus was now on the landscape, the cold, the ice, the sky and the natural. Yes, skaters could often be seen, but in a way, they became supporting actors, unrecognizable and also increasingly seen from behind.

Willem Bastiaan Tholen, Ice entertainment , 1905. The freezing cold can be felt through the chosen cold colours.

Willem Bastiaan Tholen, Ice entertainment , 1905. The freezing cold can be felt through the chosen cold colours.© Museum Gouda

This development began with the generation of Andreas Schelfhout, a renowned Romantic landscape painter. A characteristic example is the beautiful IJsvermaak (Ice entertainment, 1905) by Willem Bastiaan Tholen – an artist known to have been fascinated by ice skating – in Museum Gouda. The painting with a strong horizontal character shows a few skaters from behind, speeding on ice along a frozen canal in a largely empty landscape, where cracks and traces of previous skaters draw attention. The freezing cold can be felt through the chosen cold colours.

In the painting located in the Kröller-Müller Museum by the all-rounder Jan Toorop who rather exceptionally experimented with the topic, there is a crowd of people – indistinguishable as individual people but recognizable as people wearing skates – that want to get on the ice. Skating itself is no longer a subject.

A long way to go

This is just the precursor of what the twentieth century was to bring. Ice skating and ice fun are – at least not among the artists who belong to ‘the’ canon of Dutch art, whatever that is – no longer a subject of interest. Perhaps this is best illustrated by two exceptional paintings from the first decades of the twentieth century, painted by non-Dutch artists who had a strong connection to the country and were perhaps captivated by what they saw as the ‘exotic’ Dutch fascination with ice skating.

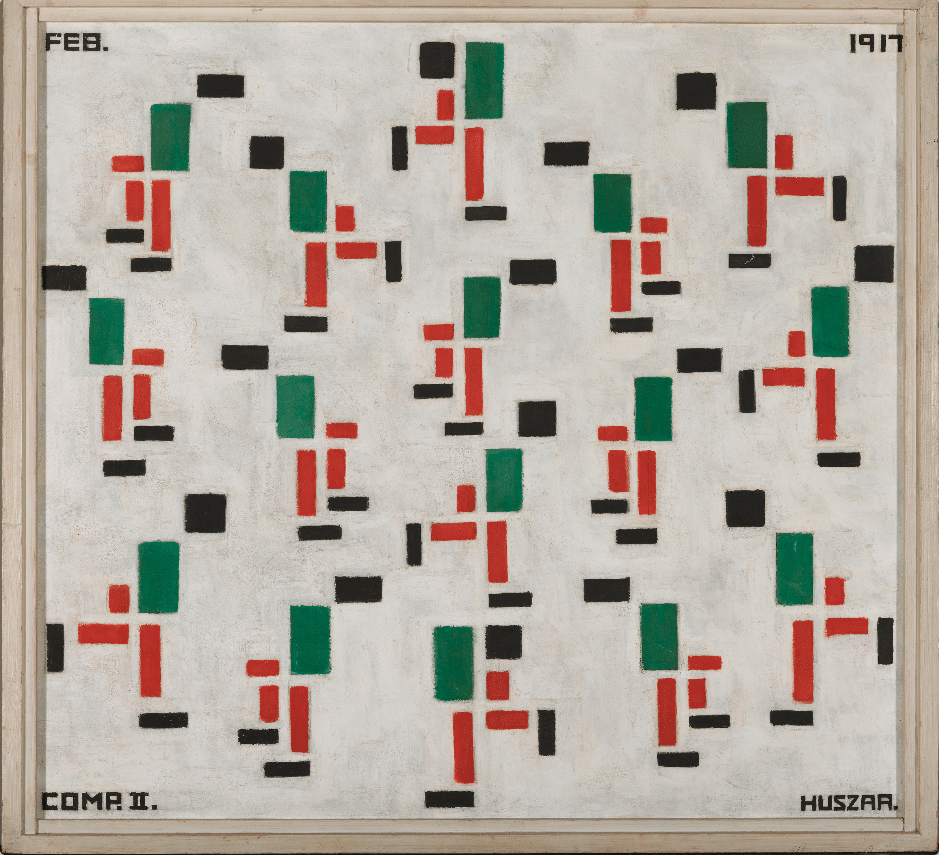

In 1917, Vilmas Huszár – one of the founders of De Stijl (The Style) – painted possibly the only, nearly abstract representation of ice skaters. It’s very fitting that the work is in the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, where it is surrounded by the oeuvre of Mondrian, who turned out to be more into dancing and jazz than ice skating.

Vilmas Huszár, Composition II (Skaters), 1917. Huszár painted possibly the only, nearly abstract representation of ice skaters.

Vilmas Huszár, Composition II (Skaters), 1917. Huszár painted possibly the only, nearly abstract representation of ice skaters.© Kunstmuseum Den Haag

Another painting rarely mentioned in publications about skaters is made by an artist that you would not immediately associate with ice fun – in fact not with fun in general. The Skaters by Max Beckmann from 1932 hangs on the other side of the ocean at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. This expressive painting with bold colour blocking has come a long way since Pieter Bruegel made the winter landscape with ice skaters into such a characteristic genre in the art of the Low Countries.