‘Xerox’ By Fien Veldman: An Anti-office Novel Full Of Silent Protest

The dullness of office life prompts workers to work as little as possible. With Xerox, Fien Veldman has written a debut about one such ‘quiet quitter’.

It was the buzzword of last summer. Quiet quitting. A catch-all term for the mindset of bored office workers, employees with insignificant jobs who attempt to do so little they might as well quit. But in this harsh, late-capitalist world, they desperately need the money, so they hang around in small stuffy rooms or hide behind the plastic plants in open-plan offices, all the while feigning to matter.

Fien Veldman

Fien Veldman© Laila Cohen

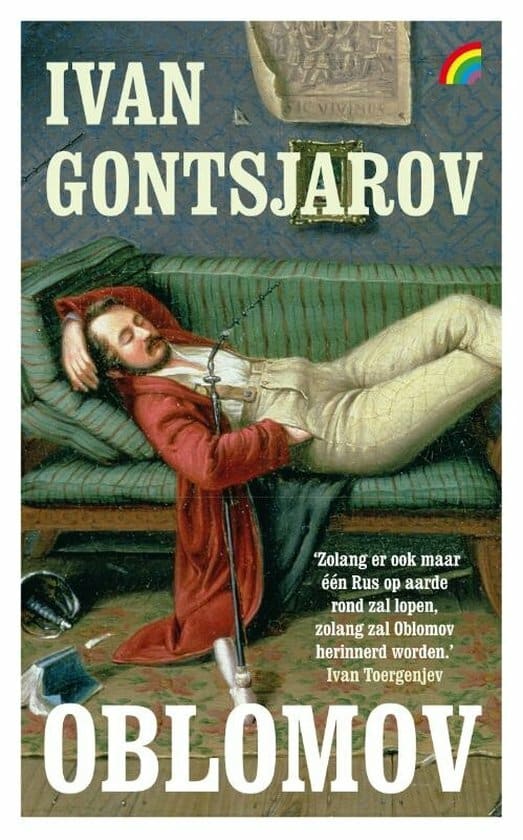

Dutch author Fien Veldman (b. 1990) has written her debut novel about Xerox about one such person chained to the office. “Sometimes I just go on the Internet,” confesses the otherwise anonymous narrator. “I don’t feel guilty about it, I get the minimum wage from which my lunch is deducted.” Later we hear, “I want to be an Oblomov, I would prefer to stay in bed all day with my head under the covers.” Unfortunately, she can’t afford to be an Oblomov because she has no one to serve her coffee in bed.

Not that nothing happens in Xerox, quite the contrary. Our narrator appears slightly traumatised by a childhood in poverty, in which an incident involving a fire seems to have played an important role. She often thinks back to that. She is trying to track down a mysterious package that has been incorrectly delivered, because she is afraid that her boss will get terribly angry. And she talks a lot, delivering whole monologues toward the printer with which she shares an office almost as if coincidently. That’s how we learn more about her childhood. But things should not get too intense as the narrator has an allergy, especially to exertion.

The anonymous narrator in 'Xerox' wants to be an Oblomov 'who prefers to stay in bed all day'

The anonymous narrator in 'Xerox' wants to be an Oblomov 'who prefers to stay in bed all day'Fien Veldman thus provides plenty of leads with which to write a story about these turbulent times, in which an anonymous place (“a city of slavery money and diminutive words”) is overgrown by garbage, because the workers have sabotaged the incinerator so subtly that they can’t fix it themselves. Also a kind of silent protest and quiet quitting. What’s more, it turns out that our narrator is not the only one with an allergy to exertion. It is truly an epidemic, especially among women between 25 and 30, as her therapist observes.

Veldman delivers her story with humour. “I can’t imagine that anyone who knows the rules of tennis would do this job,” she has her narrator say, neatly slicing through the inequality at work in office life. Meanwhile, she keeps up appearances, pretends to work hard and that everything is going the way it should. “Maybe I can just ignore this email and the problem will solve itself. (…) If I just pretend everything is fine, maybe it will be,” she notes, but at the same time she notes that these are bad times for timid people. Like herself.

Meanwhile, her relationship with the printer grows. And we get to know that Japanese-made instrument a little better ourselves too, since perhaps we should distinguish a little less between human, animal, and thing. After all, humans tend to overestimate themselves. Especially office people, as the printer itself notes. “Every colleague is a puppet, doesn’t make much difference to the office ecosystem,” posits the printer.

Veldman has written a sharp book full of pointed observations of office life, in the tradition of J.J. Voskuil

The narrator has already reached the same conclusion. Just like her, her colleagues have no names; descriptions such as ‘boss’, ‘product’ or ‘marketing’ are sufficiently clear about their position and role. Everyone is interchangeable. Even what they say is interchangeable, which Veldman subtly reveals by placing generic terms in square brackets. For example, she has marketing say to her narrator: “I sincerely believe what you do is very important (…) If we didn’t have you, then [something semi-philosophical], while I [self-deprecating joke].”

The narrator is indeed capable of connection. Not only with the printer, but with people. Although it is sometimes superficial, and she notes that she solves other people’s problems more easily than her own. And also: “I had to smile so often that I forgot my own smile.” The tragedy of the service desk employee. And yet, after an accidental collision, she connects with a real human being, a rubbish collector as it happens.

With Xerox, Veldman has written a kind of anti-office novel, a sharp book full of pointed observations of office life, in the tradition of J.J. Voskuil, which she quotes at the beginning of one of the chapters. But Xerox is more than an office novel, it is also a story about how difficult it is to form relationships when you have already become deformed during your formative years, when your very foundation has become warped by its construction. This book is a search for connections that may not be there, and a search for a new story, a new reality, which is hopefully better than this one, where office workers can be replaced by a chatbot at the snap of a finger.

Fien Veldman, Xerox, Atlas Contact, 2023, 208 pages.

Excerpt of ‘Xerox’, as translated by Elisabeth Salverda

What if I had grown up in a different place? Somewhere in another part of the country, somewhere by a lake? With a little boat? What if I had been rich? Then I never would have had this job. It wouldn’t even have occurred to me that this job existed. Perhaps I just have a huge lack of self-confidence, self-confidence that I would have had if I’d been rich. When actually it is rich people who should be in crisis. They should be asking themselves: that scholarship in New York, that internship at a cultural institution, that PhD position, that master’s at an art school, did I really earn that? But they don’t question it, because from an early age they are used to getting things. Aside from a driver’s license at eighteen, these things are, more or less, the following: piano lessons (a piano at home), good books, skiing holidays, feeling at ease in expensive spaces, unspoken rules about how loud to talk and how to sit at a table, how to say ‘carpe diem’, what a mortgage is, what smart investments are, a friend, relative or acquaintance named Emma, chess, etiquette, proverbs, the right TV programmes, a familiarity with classical music, when and to whom you should speak formally, what kind of alcohol and what kind of alcoholism is acceptable. That you’re not supposed to sit on certain chairs because they are designer or made from expensive material. How to hold a wine glass. That it’s rude to study someone’s bookshelves. The rules of tennis. And because you know all these things, you will never really, in the depths of your soul, question whether you have earned something. It’s natural and you’re not a bad person, you disagree with inequality in the world and everyone deserves the same opportunities, you’re a reasonable person, of course you’re a reasonable person, that’s how you were raised. But the subtle, ever-growing implications of this unfair distribution elude you: you think they get smaller over the years instead of bigger, and you think you can’t do anything about it yourself, that it’s a system outside yourself. Maybe subconsciously I have an inferiority complex that I will never be free of because I am ashamed of my family and ashamed of the accent I used to have. I can’t imagine that anyone who knows the rules of tennis would do this job. I can’t imagine that.