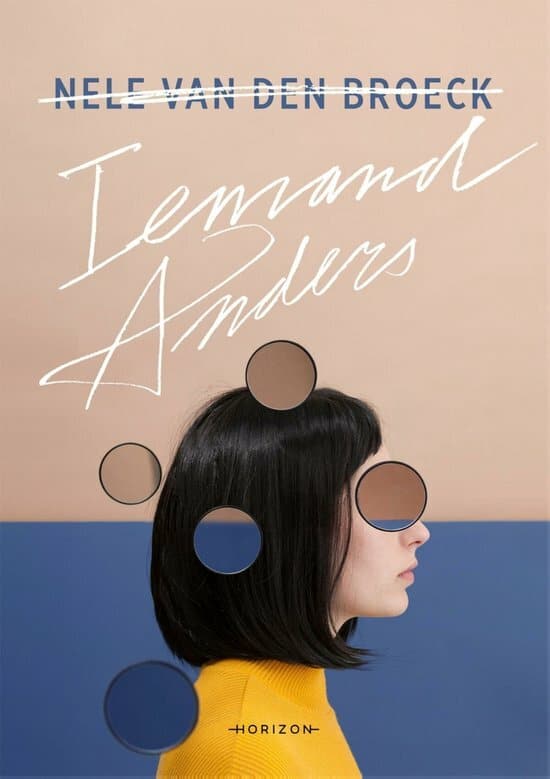

‘Iemand Anders’ by Nele Van Den Broeck: Self-Mockingly in Search of a New Existence

In Iemand anders (Someone Else), the debut novel of Belgian singer and actress Nele Van den Broeck, the main character is forced into a different role overnight. This results in an at times very comic tale of a woman searching her way in life once more.

It ended and began with a letter. One morning in October, Sandra Sanctorum finds an envelope in her letterbox. She recognises the handwriting of her husband Georg, who had not been at breakfast that morning. In the letter, he coldheartedly ends ‘twelve years of sexual exclusivity and managed cohabitation.’ Sandra’s world implodes. Is she once more simply to be Sandra Verstraeten, the daughter of the plant and flower shop owner from the ugly village where she grew up?

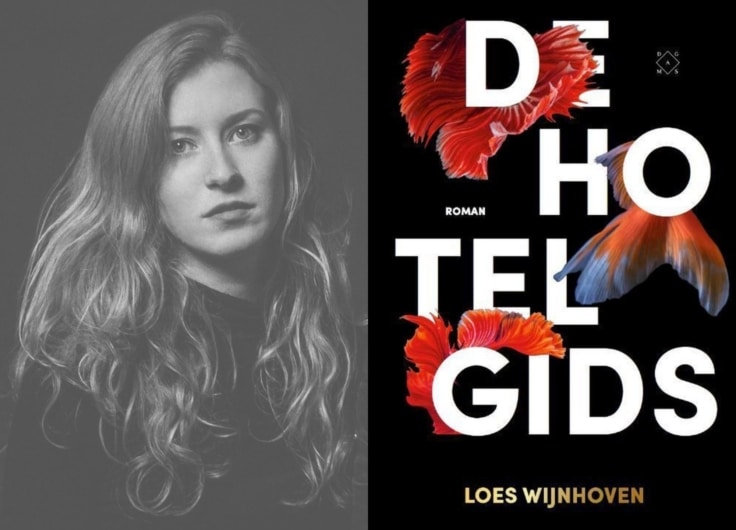

Nele Van den Broeck

Nele Van den Broeck© Horizon

That is the starting point of Iemand anders (Someone Else), the literary debut of Flemish author Nele Van den Broeck (b. 1985). In Belgium, she is already known for being a singer, in her band Nele Needs A Holiday, as a theatre maker and for her column in De Standaard newspaper, in which she explores life through song lyrics. She previously published the book Halfvolwassen (Half-grown-up), a biographical story in which she candidly recounts her failures in life and love, and the depression that sometimes plagues her.

The Sandra in her debut novel also struggles with failure and depression; she struggles with life full stop. Not much of a feminist, she had constructed her life around that of Georg, who eagerly took advantage of the fact. Not only was she the muse of this “genius” author of literary bestsellers, she was the subject of his books, and she worked at the publishing house that puts out his widely read oeuvre. Sandra is his editor and his manager to boot, she handles everything. Because Georg is obviously the kind of writer who cannot deal with e-mails and schedules, he is concerned only with his art. And his ego.

To reinvent herself, Sandra makes two snap decisions. She throws some stuff in a bag and moves back in with her parents, largely to escape the city and the publishing house where she would only be confronted by Georg anyway. She also makes a to-do list of how she wants to celebrate her life from now on: smoking, drinking, having sex every day, enjoying being lazy and a few other things generally seen as unhealthy, inappropriate or problematic behaviour. To destroy Mrs Sanctorum, Sandra must become her opposite.

Nele Van den Broeck writes with pace, humour, and a generous dose of self-mockery

In short, punchy chapters, Nele Van den Broeck describes this search for a new existence, a new self, interspersed with reflections on her old life, and how that turned out. She does so with pace, humour, and a generous dose of self-mockery. Sandra turns out to have a book of her own, but as the famous ex of an even more famous writer, she cannot and does not want to publish it under her own name. She wants the book to speak for itself. And Sandra chooses the pseudonym Nele Van den Broeck, the name of ‘a woman who loved cycling or was a city councillor for a right-wing centre party’.

During her quest, she visits doctors, therapists, and speaks with chance passers-by. From the first of these encounters, it is clear that Van den Broeck has experience with therapy, which she often describes with humour as well. ‘Three hundred years of enlightenment and then that cow says something like that,’ she comments when Doctor Verdin comes out with the cliché ‘the first step to healing is believing it will get better’.

Nele Van den Broeck paints a nuanced portrait of a searching thirty-something, sometimes cheerful, sometimes a little wry

Others with whom Sandra connects are often just as soul-searching as she is. Like the floaty Alma, who supplies the village with necessary mind-altering drugs. Or the silent Victor, the manager of the village shop where just about everything is for sale (Sandra gets her daily dose of booze and tobacco there), who finds an outlet in a kind of Japanese bondage. Sandra willingly allows herself to be initiated, but she is no longer the puppet she was in Georg’s hands. She stays partly in control, as she realises what went wrong in her marriage: ‘I had manoeuvred myself into a position of ultimate loneliness.’

The novel Sandra is writing as Nele, Bruises, flops at first but by a twist of fate ends up being a hit. Perhaps this debut novel did not need that more or less happy ending, but it’s a minor detail.

Along the way, Van den Broeck paints a nuanced portrait of a searching thirty-something, sometimes cheerful, sometimes a little wry. Meanwhile, she pokes fun at the often-snobbish literary world, and at the promise of salvation via all kinds of therapists, miracle remedies or self-help. In the end, it turns out that humour is often still the best therapy. Even if it has a dark edge.

Nele Van den Broeck, Iemand anders, Horizon, 2023, 256 pages

Excerpt of 'Iemand anders', as translated by Elisabeth Salverda

The morning after the end of my life, I took a shower. That was something anyway. A clean pair of knickers and my tracksuit. I charged my phone and managed to dial down my disappointment when it turned out that Georg had not called a couple of times. Five missed calls from Pierre. I say five, but it was a multiple of – after five I had stopped counting, like everyone else with fingers. Despite the excessive number of panic calls, I wasn’t nervous when I called back. It was Pierre, after all.

‘Sandra, where were you? I need you!’

‘Yes. I know.’

The other end of the line remained silent for a moment at this unexpected answer – no apology, no explanation, no phone that had fallen behind the heater and could only be freed with devious ingenuity and a knitting needle.

‘How much time do you need to edit The Rot, do you think? When can you start on it?’

‘Pierre. I can’t. Georg…’

My sentence broke off. I couldn’t get it out of my mouth.

‘I’m sick. I can’t come to work.’

I heard Pierre remain silent. Sandra Sanctorum sick? Sandra Sanctorum is never sick.

‘It’s serious,’ I said finally, entirely truthfully. ‘I will be out of the running for a long time. You’d better start looking for someone to replace me. I’ll get you a doctor’s note.’

‘Of course, Sandra,’ Pierre said, half whispering, half crying. ‘I understand completely.’

‘Contact with Georg will have to go directly through him for a while, will that work? Until he finds an agent. I’m sure that won’t be a problem, they’re lining up.’

‘Naturally, of course, that goes without saying,’ Pierre said.

Had he found a fourth synonym, he would have used that too.

We both knew that nothing went without saying in direct contact with Georg. I had been his decoding machine all these years.

‘If there’s a problem you can call me,’ I lied.

‘Thank you, Sandra. A speedy recovery.’

I hung up. The idea of recovery seemed absurd. I was not a sock with a hole in it. I was the hole in the sock.

‘Psychiatrist, Karst’ I typed in with a far-too-big thumb on a screen that was far too small. There was just the one – a website featuring Rodin’s The Thinker against a backdrop of mandalas. Well then. I booked an appointment with Doctor Laura Verdin and her doctor’s note.

I took my body outside and let it run. For over an hour I walked nowhere at all, then I showered again. I put on my second clean pair of knickers that day, a linen shirt, and my jeans from yesterday. In my pocket smouldered Georg’s letter.

I tore off the unwritten part. What remained was barely bigger than a greeting card, which I folded over a few more times and pressed as flat as possible. Around my phone was a sand-coloured leather protective case, which I managed to get loose. I put my folded piece of paper in the case, it fit perfectly. When I put my phone back with a click, there was nothing to see. The letter was gone.

As if through a thick fog, I went down the stairs, through the house, into the shop. My mother was hunched over a cash book.

‘Georg left me,’ I said, ‘I don’t know where to go. I’ll stay here for a while until I do.’

My mother nodded. That was all, she nodded. I had said it. Now it was true.

‘Will you tell Dad?’

She nodded again. It’s not often my mother doesn’t talk. Her silence began to become more frightening the longer it went on, as if all language had been blown out of this moment by a sudden gust of wind or a stroke. Two moments later, a wave of relief swept across her face.

‘After rain comes sunshine.’

That’s what she said.

After rain. Comes sunshine. Then she started singing. A song about the seasons, I didn’t know it.

‘Thank you, Mum,’ I said, as if the song had cheered me up.

She smiled, proud of her impromptu rendition of wise old mother.

I had comforted her.

‘Oh, my baby. Stay as long as you like.’

My vertebrae inched a fraction together. If I didn’t watch out, I would soon be no taller than a toddler.

On my old girl’s bike, I rode to Karst’s tiny library, registered, and borrowed five books. When I got back home, I sat down – not in the shop, but on a bench that stood in the gardens to show customers what a bench in a garden looks like. A show garden bench.

It was a mild October day, my father was grafting saplings, I was reading like someone possessed. I read what there was to read. A couple of historical novels, one set during the Eighty Years’ War, another during the Hundred Years. The biography of a local composer. The English translation of a Russian classic. A 2004 non-fiction book on quantum physics. Twenty years ago, string theory was very promising.