Yair Callender Brings the Everyday Into Ceremonial Art

Yair Callender’s sculptures and installations are part of a tradition with a religious element. It’s difficult however to pin the Surinamese-Dutch artist down to one approach, as both he and his art are as philosophical as they are practical.

What is art? The most pragmatic answer: the things that we find between the neutral, white walls of a museum. Things like archaeological finds and objects from the Middle Ages are a little more nuanced. We know that these pieces once fulfilled a function in daily or spiritual life, if only because the corresponding museum texts tell us that. But even then, we probably also consider them with aesthetic criteria in mind. It then becomes tempting to see form and function as the result of a conscious artistic choice.

Yet the museum view is only one approach, notes visual artist Yair Callender (1987). He has a predilection for ceremonial and religious art, from different backgrounds and traditions. This often involves strict rules. For example, to make ritual object X you can only use material Y, while object Z can only be displayed during a full moon.

The classic indoor exhibition is also just one way of presenting art, Callender emphasises. His work can regularly be found within the ‘white cube’ – as the neutral exhibition space is often termed. He participated in group exhibitions and in 2018 had a solo exhibition in the art space 1646, in The Hague. He finds it interesting to discover how a work of art contrasts with its surroundings and how it finds a place in people’s daily lives.

The coherence behind the experience

Callender’s sculptures and installations are therefore also found outside the walls of exhibition spaces, out in the public realm. It was in this context that he probably had his first important experience with art, hanging around the streets as a teenager, he preferred places with interesting images or architectural features. There’s now one of his permanent sculptures in Suriname (Monument VI – Monument to Moengo, 2017). Callender dreams of making permanent works of art for public spaces in the Netherlands too.

'Monument VI - Monument to Moengo' in Suriname. Callender dreams of making permanent works of art for public spaces in the Netherlands too.

'Monument VI - Monument to Moengo' in Suriname. Callender dreams of making permanent works of art for public spaces in the Netherlands too.© Yair Callender

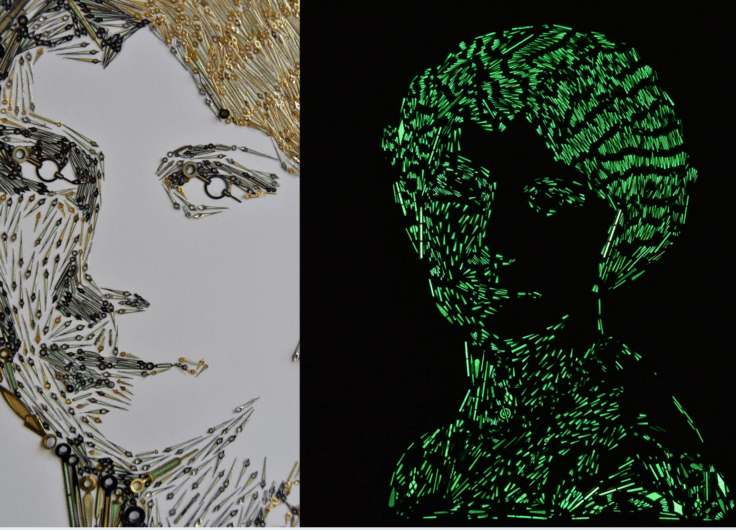

Callender describes his art as a combination of two- and three-dimensional. This puts him in a tradition that is partly religious – think of wood carvings, facade sculptures and reliefs that can be found in different religious contexts. Even if it involves ‘flat’ work, such as paintings or mosaics, it usually has a function within the layout and purpose of the space.

This cohesion evokes an experience that can be sacral, but is no less sincere for it. Callender – who is religious but does not adhere to a specific religion – emphasises the role of spirituality in his art. For him, these two things are closely linked.

A carpenter with an artist’s CV

There’s a very everyday side to spirituality. Sometimes people have altars in their own living spaces, and places of worship are ultimately ‘just’ buildings. Callender is therefore not just philosophically inclined. He’s also very rooted and practical – evident from our conversation, in his work and his own life. To be financially independent from being an artist, he works as a carpenter for a company that specialises in the restoration of monuments, ornaments, and classical woodcarvings. He laughs, and says that at the time, he simply turned up there with his artist CV.

'For the vision of Abou ben Adhem' (2018), solo exhibition in 1646 (The Hague).

'For the vision of Abou ben Adhem' (2018), solo exhibition in 1646 (The Hague).© Yair Callender

There’s also something very mundane in his choice of materials. He uses concrete, iron and wood, but also corrugated iron and flowers. There is always something that reminds you of things outside the exhibition space, hints of architecture or furniture, the church you might go to, or your own living room. You can even sit on some of his sculptures, including an untitled work from 2014, which was shown during the Unfair art fair.

There is something very mundane in Callender's choice of materials. He uses concrete, iron and wood (Untitled, installation photo Unfair Amsterdam 2014)

There is something very mundane in Callender's choice of materials. He uses concrete, iron and wood (Untitled, installation photo Unfair Amsterdam 2014)© Yair Callender

Perhaps distinguishing the spiritual from the practical, is moot, I think when Callender talks enthusiastically about a centuries-old tradition of ceremonially bringing sculptures ‘to life’ by carrying them around. This was already happening in ancient Egyptian and Greek times, and it still happens in Caribbean and Surinamese cultures, among others.

The formal monument

Callender’s interest in ceremonial objects also manifests itself in a fascination for monuments – something he also produces. Monuments formed the subject matter for his graduation project at art school. His key questions were; how does a certain object actually become a monument; and can we simply label an object as such, or are there also certain formal properties it must have?

Installation photo 'Jamsessie' (2018), exhibition with Matthias Grothus in Kadmium, Delft

Installation photo 'Jamsessie' (2018), exhibition with Matthias Grothus in Kadmium, Delft© Yair Callender

His research ran in parallel with his interest in spirituality. He discovered that there is a long tradition of visual work as an attempt to capture things that cannot be expressed in words. That led him to protocols around formal properties – a certain colour or shape, for example, can stand for an abstract idea. The interesting thing for Callender, following on from that, is whether he can bend or even break those rules in his art.

As an example, he mentions the two-part You need the words to see the spaces between them (2018). One part hangs on the wall, slightly above eye level, and the other is attached to a skylight. On the first one, he drew a galaxy with crayons, and deliberately chose those crayons because of the somewhat childish impression they make.

Detail of the installation 'You need the words to see the spaces between them'.

Detail of the installation 'You need the words to see the spaces between them'.© Yair Callender

On the top piece he drew a geometric shape from Islamic culture, but contrary to custom, he omitted the lines. Only the nodes are left, like a second starry sky. It gives the work something layered – first the reality, a little above that the geometry, and then you look beyond that to the sky.

Callender isn’t at all concerned with proving proof that there is some kind of math behind everyday reality, and he admits that he would need solid reasoning for that. But it is precisely in art that you can explore such an idea without it being right or wrong per se.

Installation as a creative process

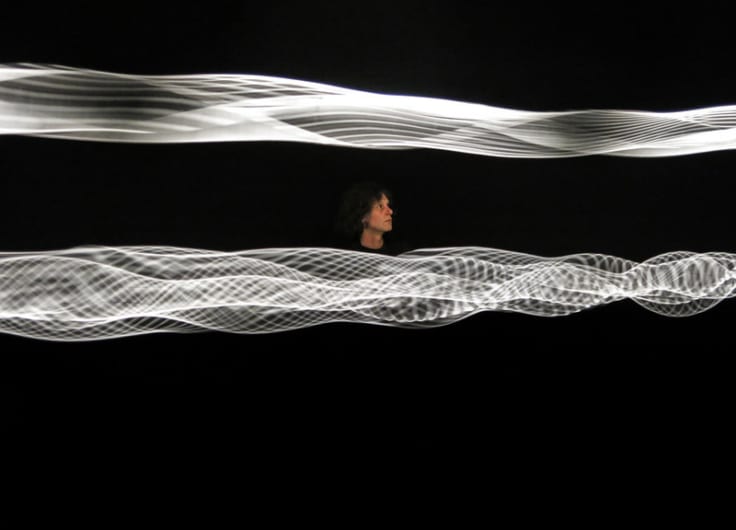

Many of Callender’s installations are made up of different fragments or modules. They give you the feeling that they can just be rearranged again. He distinguishes between two creative phases – on the one hand, the creative process in the studio, where he actually makes objects, and on the other hand, the installation of those works.

In situ, he sees them within the physical exhibition space and the context of the exhibition he’s been asked to be part of. What he’s already made suddenly tells him something new, and it’s that feeling that leads him during the installation phase.

Sometimes intervention is necessary. As an example, he mentions Omstand, an art institute in Arnhem where he exhibited in a kind of greenhouse. It was a busy space, with so much glass and different types of beams. So he decided to cover the floor with gravel, like a Japanese Zen Garden, in which he displayed his sculptures directly on the ground, without plinths.

The gravel was also a way to bring together the individually crafted objects, despite their different characters. This new context gave them a new meaning. Callender describes it as a new phase in their lives.

On his phone, he shows a ‘detached’ wall sculpture-like work that he has exhibited in various ways. At Omstand, he displayed it on its ‘back’ on the ground, but in Kadmium art centre in Delft, it was at eye level, carried by a kind of trolley. The concrete object can therefore be shown in different ways even within the same exhibition.

The construction is not only adjustable but also movable. The neutral exhibition space on the one hand, and the carrying of sculptures on the other – they appear to be so much closer to each other than you would initially think.